East Hillside/Endion Neighborhood Transportation Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

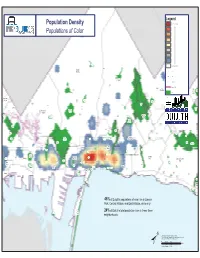

Population Density Populations of Color

Legend Legend Population Density Highest Population Density Populations of Color Sonside Park Lowest Population Density Duluth Heights School Æc Library Kenwood Hospital or Clinic Recreational Trail Rice Lake Park Woodland Athletic Lake Complex Park Annex Pleasant View Park Bayview Duluth Heights Community Heights Recreation Cntr Hartley Field Hartley Park Downer Park Janette Cody Pennel Park Pollay Arlington Park Piedmont Athletic Complex Morley Heights Hts/Parkview Oneota Park Piedmont Hunters Community Recreation Center Park Bagley Nature Area (UMD) Brewer Park Chester Park Bellevue Park Amity Park Amity Creek Park Enger Chester Quarry Municipal Copeland Lakeview Park Community Grant Community Park Golf Course Center Recreation Center Park-UMD Enger Hawk Park Ridge Hawk Ridge Nature Reserve Hilltop Park East Hillside Lincoln Congdon Park Old Park Main Cascade Park Park Portland Wheeler Square Athletic Washington Congdon Complex Central Com Rec Memorial Ctr Community Recreation Center Denfeld Hillside Park Lakeside-Lester Central Park Park Russell Midtown Civic Square Spirit Park Center Point of Rocks Park Valley Wade Sports Point of Complex Rocks Park Manchester Lincoln Square Lake Place Plaza Endion Leif Erickson Rose Garden Park Corner of Park the Lake CBD Park Lakewalk Washington East Square Irving Bayfront Park Oneota Grosvenor Square Lester/Amity Park Canal Park North Shore University Park Kitchi Gammi Park Franklin Park 46% of Duluth's populations of color live in Lincoln Park, Central Hillside, and East Hillside, while only Park 24% of Duluth's total population lives in these three Rice's Point Boat Landing Point neighborhoods. Data Source: Minnesota Population Center. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0 ± Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota 2011. -

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Existing Conditions Summary February 2021

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Existing Conditions Summary February 2021 Presented to Duluth Transit Authority Prepared by Connetics Transportation Group 1.0 Introduction In August 2020, the Duluth Transit Authority (DTA) engaged Connetics Transportation Group (CTG) to conduct a Comprehensive Operations Analysis (COA) of their fixed-route transit system. This technical memorandum presents the methodology and findings of the existing conditions analysis for the COA. The COA is structured around five distinct phases, with the existing conditions analysis representing Phase 2 of the process. The following outlines each anticipated phase of the COA with corresponding objectives: Phase 1 Guiding Principles: Determines the elements and strategies that guide the COA process. Phase 2 Existing Conditions: Review and assess the regional markets and existing DTA service. Phase 3 Identify and Evaluate Alternatives: Create service delivery concepts for the future DTA network. Phase 4 Finalize Recommended Network: Select a final recommended network for implementation. Phase 5 Implementation and Scheduling Plan: Create a plan to executive service changes and implement the recommended network. The DTA provides transit service to the Twin Ports region, primarily in and around the cities of Duluth, Minnesota and Superior, Wisconsin. In August 2020, CTG worked with DTA staff and members of a technical advisory group (TAG) to complete Phase 1 of the COA (Guiding Principles). This phase helped inform CTG of the DTA and TAG member expectations for the COA process and desired outcomes of the study. They expect the COA process to result in a network that efficiently deploys resources and receives buy-in from the community. The desired outcomes include a recommended transit network that is attractive to Twin Port’s residents, improves the passenger experience, improves access to opportunity, is equitable, is resilient, and is easy to scale when opportunity arises. -

2019 7:00 PM Council Chamber

411 West First Street City of Duluth Duluth, Minnesota 55802 Minutes - Final City Council MISSION STATEMENT: The mission of the Duluth City Council is to develop effective public policy rooted in citizen involvement that results in excellent municipal services and creates a thriving community prepared for the challenges of the future. TOOLS OF CIVILITY: The Duluth City Council promotes the use and adherence of the tools of civility in conducting the business of the council. The tools of civility provide increased opportunities for civil discourse leading to positive resolutions for the issues that face our city. We know that when we have civility, we get civic engagement, and because we can’t make each other civil and we can only work on ourselves, we state that today I will: pay attention, listen, be inclusive, not gossip, show respect, seek common ground, repair damaged relationships, use constructive language, and take responsibility. [Approved by the council on May 14, 2018] Monday, January 14, 2019 7:00 PM Council Chamber ROLL CALL Present: 8 - Councilor Gary Anderson, Councilor Zack Filipovich, Councilor Jay Fosle, Councilor Barb Russ, Councilor Joel Sipress, Councilor Em Westerlund, Councilor Renee Van Nett and President Noah Hobbs PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ELECTION OF OFFICERS PUBLIC HEARING: State Project No. 6982-328, Local Road Improvements on 46th Avenue West, 27th Avenue West, Garfield Avenue and Railroad Street for the Twin Ports Interchange Project REPORTS FROM THE ADMINISTRATION REPORTS FROM OTHER OFFICERS 1. 19-008 MN Department of Health, Quarterly Report Indexes: Attachments: MN Department of Health, Quarterly Report This Informational Report was received. -

Guide to the Duluth Area Attractions

Guide to the Duluth Area Attractions Summer 2018 2018 Adventure Zone Family Fun Center 218-740-4000 / www.adventurezoneduluth.com SUMMER HOURS: Memorial Day - Labor Day Sunday - Thursday: 11am – 10pm Friday & Saturday 11am - Midnight WINTER HOURS: Monday – Thursday: 3 – 9pm Friday & Saturday: 11am – Midnight Sunday: 11am – 9pm DESCRIPTION: “Canal Park’s fun and games from A to Z”. There is something for everyone! The Northland’s newest family attraction boasts over 50,000 square feet of fun, featuring multi-level laser tag, batting cages, mini golf, the largest video/redemption arcade in the area, Vertical Endeavors rock climbing walls, virtual sports challenge, a kid’s playground and more! Make us your party headquarters! RATES: Laser Zone: Laser Tag $6 North Shore Nine: Mini Golf $4 Sport Plays: Batting Cages or Virtual Sports Simulator $1.75 per play or 3 plays for $5 DIRECTIONS: Located in Duluth’s Canal Park Business District at 329 Lake Avenue South, just blocks from Downtown Duluth and the famous Aerial Lift Bridge. DEALS: Adventure Zone offers many Daily Deals and Weekly Specials. A sample of those would include the Ultra Adventure Pass for $17, a Jr. Adventure Pass for $11, Monday Fun Day, Ten Buck Tuesday, Thursday Family Night and a Late Night Special on Fri & Sat for $10! AMENITIES: Meeting and Banquet spaces available with catering options from local restaurants. 2018 Bentleyville “Tour of Lights” 218-740-3535 / www.bentleyvilleusa.org WINTER HOURS: November 17 – December 26, 2018 Sunday – Thursday: 5 - 9pm Friday & Saturday: 5 – 10pm DESCRIPTION: A non-profit, charitable organization that holds a free annual family holiday light show – complete with Santa, holiday music and fire pits for roasting marshmallows. -

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries June 2021

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries June 2021 Presented to Duluth Transit Authority Prepared by Connetics Transportation Group DTA Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries Recommended Draft Network Route Frequency and Span Summary DTA Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries Route Replacement Overview Table Previous Route Recommended Draft Network Replacement Route 1 101 Route 2 101, 103 Route 2F Service to Fon du Lac discontinued Route 2X* 103 Route 3 101, 109 Route 3X* 109 Route 4+ 109 Route 5 101, 103, 107, 108 Route 6 101 Route 7 101, 103 Route 7A 101 Route 7X* 103 Route 8 107, 108 Route 9M 108 Route 9MT 107, 108 Route 10 102, 104, 108, 113 Route 10E+ 102, 104, 113, Route 10H 102 Route 11 102, 105 Route 11K 102, 105, 106, 112 Route 11M+ 105, 112 Route 12 106 Route 13 104, 112 Route 14W Service to Observation Hill discontinued Route 15 113 Route 16 110, 111 Route 16X* 110, 111 Route 17+ 110 Route 17B Service to Billings Park discontinued Route 17S 110 Route 18 112 Route 19 114 Route 23 104, 105 Route S1 101, 109 *Peak Period Express services were reallocated into frequency on local services +Sections of this route discontinued. Check specific route changes for more details Routes 101 & 102 denote high frequency (pre-BRT) service DTA Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network Individual Route Summaries Route 101: Spirit Valley-DTC-UMD Route 101 is one of two, pre-BRT routes that make up the high frequency spine of the Better Bus Blueprint Recommended Draft Network. -

Legislative Brief

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 2 I. PLAINTIFFS' LEGISLATIVE REDISTRICTING PLAN ACCURATELY REFLECTS THE CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS OF THE STATE .......................................................... 2 A. Legislative Maps Should Begin with Logical Groupings of Counties and Cities Where Possible ................................................. 2 B. House Districts Should Be Drawn Before Senate Districts .............. 3 C. Districts Should Use Rivers as Natural Boundary Lines .................. 5 D. Townships Should Be Paired With Their Related Cities or Towns Whenever Possible ................................................................ 5 II. PLAINTIFFS' LEGISLATIVE REDISTRICTING PLAN BENEFITTED FROM PUBLIC COMMENT AND LEGISLATIVE EXPERTISE ................................................................................................. 6 ARGUMENT ...................................................................................................................... 9 I. PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSED LEGISLATIVE DISTRICTS SATISFY CONSTITUTIONAL REQUIREMENTS ................................................... 9 A. The Proposed Legislative Districts Satisfy the Panel's Population Equality Requirements .................................................... 9 1. House District 26A .............................................................. -

City of Duluth 2016 Housing Indicator Report

City of Duluth 2016 Housing Indicator Report Prepared by: Released: June 2018 Community Planning Division City Hall Room 208 Duluth, MN 55802 http://www.duluthmn.gov/community-planning/ Executive Summary Purpose The Community Planning Division publishes the Housing Indicator Report annually to provide a snapshot of the current housing markets and to understand how those markets have changed over time. We include demographic and workforce statistics to provide context about what kinds of housing options are available and affordable to a diverse range of our community members. Key Findings Average and median home sale price have gradually increased over the past decade and while homeowners’ median household income seems to have stagnated in the past few years, average homeownership costs still appear to be affordable to middle income homeowners. From 2014 to 2015 the average market rent increased drastically by almost $100 a month and while it continued to increase in 2016 to $920, it was a less drastic increase than in the previous year. Average market rate rental housing has not been affordable to the majority of renter households for at least a decade and that trend continues in 2016. This year we focused on some of the systemic issues that contributed to creating the disparities and the wealth gap we see between the higher and lower income neighborhoods in our city. With a better understanding of these disparities and their causes, there can be more informed decisions made about the allocation of services and resources. Examining these historical disparities also provides more context and insight to our housing market. -

City of Duluth Duluth, Minnesota 55802

PC Packet 01-12-2021 411 West First Street City of Duluth Duluth, Minnesota 55802 Meeting Agenda Planning Commission. Tuesday, January 12, 2021 5:00 PM Council Chamber, Third Floor, City Hall, 411 West First Street To view the meeting, visit http://www.duluthmn.gov/live-meeting Call to Order and Roll Call Public Comment on Items Not on Agenda Approval of Planning Commission Minutes PL 20-1208 Minutes 12/8/20 Consent Agenda PL 20-185 Variance to Side and Front Yard Setbacks to Match Existing Foundation at 2001 W 8th Street by Kurt Herke PL 20-189 Interim Use Permit for a Vacation Dwelling Unit at 7 N 19th Avenue W, Unit 1, by Newcastle 8 LLC PL 20-190 Interim Use Permit for a Vacation Dwelling Unit at 7 N 19th Avenue W, Unit 2, by Newcastle 8 LLC PL 20-191 Interim Use Permit for a Vacation Dwelling Unit at 7 N 19th Avenue W, Unit 3, by Newcastle 8 LLC PL 20-192 Interim Use Permit for a Vacation Dwelling Unit at 7 N 19th Avenue W, Unit 4, by Newcastle 8 LLC Public Hearings PL 20-194 Variance to Off-Street Parking Requirements at 310 N 9th Avenue E by Beverly Ricker Communications - Land Use Supervisor Report - Historic Preservation Commission Report - Joint Airport Zoning Board Report City of Duluth Page 1 Printed on 1/4/2021 Page 1 of 78 PC Packet 01-12-2021 Planning Commission. Meeting Agenda January 12, 2021 - Duluth Midway Joint Powers Zoning Board Report NOTICE: The Duluth Planning Commission will be holding its January 12, 2021 Special Meeting by other electronic means pursuant to Minnesota Statutes Section 13D.021 in response to the COVID-19 emergency. -

Minnesota Statewide Historic Railroads Study Final MPDF

St. Michael Big Marine ! ! Anoka Lake ! Berning Mill !Rogers Champlin ! Anoka HennepinMis siss Fletcher ip Maple Island ! pi ! R Lino Lakes ! i Centerville v ! er ! on Hanover ! Hugo ti Wright ! Coon Creek Maple Grove ! Hennepin arnelian Junc rcola Anoka Withrow C ! A Burschville ! ! ! !Osseo Ramsey te Bear Beach Whi ! Bald Eagle ! !Dupont !Corcoran !Brooklyn Park on ! ! Dellwood Rockford ! Fridley White di ! White me ! C Bear luth Juncti Lake Sarah ardigan Bear ahto ! Du ! Lake !M Lake !Leighton New Junction Vadnais Heights ! Stillwater ! Columbia Brighton ! ! Lor ! ! ood Heights etto rchw ! ! Bi Hamel ! ! ! Little Canada Medi Robbinsdale North c Bayport ine La ! ! Ditter ! St. Paul S Lon ! t Roseville . ! C gL r Maple Plain k Golden Gloster o e ! a i k ! Valley ! x e ! ! Lake Elmo R i Lyndale ! ! v ! Oakdale e ! r ! Midvale Ramsey ! Wayzata Washington Minneapolis Spring P Minnet ! onka Saint Paul St. D ! ! M . Oakbury Lakeland ! ark Lake ills ! Mound ! ! Louis D ! Minnetonka ! D . ! Park ! . ! . ! ! D . Deephaven ! ! ! West Highwood . ! Hopkins ! D St. Paul ! Glen Lake . ! ! ! Afton D ! St. Bonifacius M ! Excelsior . .! is Oak Terrace! South s ! i s s D ! St. Paul .! ! Fort . i ! Mendota . p Carver p Snelling . ! i D . ! Waconia R iver Newport ! D Chanhassen .! D ! ! Atwood D !Victoria Inver Grove ! ! D Eden Prairie .! St. Paul Cottage Grove ! !D Park .! Oxboro ! Bl oo D Hennep Bloomington .! mington Ferry ! ! Nicols Wescott ! D . ! in ! er . ! iv ! Augusta ta R ! Langdon ! so D nne . ! i ! ! M D Map adapted from the MN DNR divison of Fish and Wildlife 100k Lakes and Rivers and 100k Hydrography, Railroad Commissioners Map of Minnesota, 1930, and MN DOT Abandonded Railroads GIS data. -

Minnesota Statewide Multiple Property Documentation Form for the Woodland Tradition

Minnesota Statewide Multiple Property Documentation Form for the Woodland Tradition Submitted to the Minnesota Department of Transportation Submitted by Constance Arzigian Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse July 2008 MINNESOTA STATEWIDE MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM FOR THE WOODLAND TRADITION FINAL Mn/DOT Agreement No. 89964 MVAC Report No. 735 Authorized and Sponsored by: Minnesota Department of Transportation Submitted by Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse 1725 State Street La Crosse WI 54601 Principal Investigator and Report Author Constance Arzigian July 2008 NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug. 2002) (Expires 1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. __X_ New Submission ____ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Woodland Tradition in Minnesota B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) The Brainerd Complex: Early Woodland in Central and Northern Minnesota, 1000 B.C.–A.D. 400 The Southeast Minnesota Early Woodland Complex, 500–200 B.C. The Havana-Related Complex: Middle Woodland in Central and Eastern Minnesota, 200 B.C.–A.D. -

Xii. Pastoral Records

XII. PASTORAL RECORDS Record of Ministerial Service The basic format used for printing the record is: • Ed: (Degree) (School) (Year granted), (Repeat as necessary); Adm: PM (or OT or P as appropriate) (Year); FM (Year); Ord: D, if applicable (Year); App: (Conference - unnecessary if all service is in the Minnesota Conference) (Church or Special Appt.) (First year appt.), (Repeat as necessary). Necessary variations are made to fit differing circumstances. For example, churches served when the pastor’s appointment was “to attend school,” are listed in parentheses following “AS” and the year. Pastoral records contain official appointments by the bishop and do not include ministries or churches served on a supply basis. Post retirement appointments are not listed. • Abbreviations include: OT (on trial); P (provisional); PM (provisional member); FM (full member); D (deacon); FD (full deacon); E (elder); Ed (education); Adm (admitted); Comm (commissioned); Ord (ordained); AS (attending school); DS (district superintendent); Ct (circuit); Sup (supernumerary); SL (sabbatical leave); LOA (leave of absence); DL (disability leave); IncL (incapacity leave); FamL (family leave); PersL (personal leave); R (retired); RE (retired full elder); RS (retired supply); RM (retired minister); RL (retired local pastor); NA (not appointed); PE (provisional elder); HL (honorable location). Please report errors and omissions to the conference secretary. A. Elders in Full Connection AASTUEN, HOLLY WILLIAMS—Ed: BA St Olaf 1982; MDiv Iliff 1988; Adm: PM 1986; FM 1990; -

Lower Chester Park Mini-Master Plan February 2018 Acknowledgments

LOWER CHESTER PARK MINI-MASTER PLAN FEBRUARY 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Consultant: City of Duluth: SAS+ASSOCIATES, Inc. Mayor Emily Larson Stakeholder Groups: City Council Members Zack Filipovich CONGDON-LOWER CHESTER HOCKEY (CLCH) Jay Fosle DULUTH AREA HOCKEY ASSOCIATION (DAHA) Howie Hanson NEIGHBORS OF LOWER CHESTER PARK (NOLCP) Barb Russ Joel Sipress Elissa Hansen Project Coordinator: Noah Hobbs James M. Shoberg, PLA Gary Anderson Em Westerlund Duluth Parks & Recreation 411 West First Street Parks Commission Duluth, MN 55802 John Schmidt- President Phone: 218-730-4300 Erik Torch- Vice President Email: [email protected] Amanda Crosby www.DuluthMN.gov/parks Dudley Edmondson Tjaard Breewuer Dennis Isernhagen Britt Rohrbaugh Tiersa Wodash Dean Vogtman Michael Schraepfer Kristin Bergerson City Staff William Roche, Parks Manager Jim Shoberg, Project Manager Hank Martinson Jim Filby-Williams Erik Birkeland 2 LOWER CHESTER PARK CONTENTS 01. SUMMARY AND OVERVIEW..............................................................4 02. EXISTING CONDITIONS.....................................................................4 HISTORIC AERIAL PHOTOS..........................................................5 NEARBY PARK EVALUATION.......................................................6 HISTORY OF THE MINI MASTER PLAN..........................................6 03. STAKEHOLDER GROUPS.....................................................................8 TIMELINE.......................................................................................8 DAHA BY