Snively's Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

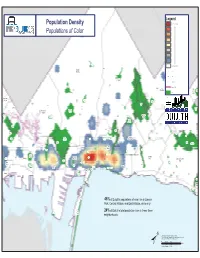

Population Density Populations of Color

Legend Legend Population Density Highest Population Density Populations of Color Sonside Park Lowest Population Density Duluth Heights School Æc Library Kenwood Hospital or Clinic Recreational Trail Rice Lake Park Woodland Athletic Lake Complex Park Annex Pleasant View Park Bayview Duluth Heights Community Heights Recreation Cntr Hartley Field Hartley Park Downer Park Janette Cody Pennel Park Pollay Arlington Park Piedmont Athletic Complex Morley Heights Hts/Parkview Oneota Park Piedmont Hunters Community Recreation Center Park Bagley Nature Area (UMD) Brewer Park Chester Park Bellevue Park Amity Park Amity Creek Park Enger Chester Quarry Municipal Copeland Lakeview Park Community Grant Community Park Golf Course Center Recreation Center Park-UMD Enger Hawk Park Ridge Hawk Ridge Nature Reserve Hilltop Park East Hillside Lincoln Congdon Park Old Park Main Cascade Park Park Portland Wheeler Square Athletic Washington Congdon Complex Central Com Rec Memorial Ctr Community Recreation Center Denfeld Hillside Park Lakeside-Lester Central Park Park Russell Midtown Civic Square Spirit Park Center Point of Rocks Park Valley Wade Sports Point of Complex Rocks Park Manchester Lincoln Square Lake Place Plaza Endion Leif Erickson Rose Garden Park Corner of Park the Lake CBD Park Lakewalk Washington East Square Irving Bayfront Park Oneota Grosvenor Square Lester/Amity Park Canal Park North Shore University Park Kitchi Gammi Park Franklin Park 46% of Duluth's populations of color live in Lincoln Park, Central Hillside, and East Hillside, while only Park 24% of Duluth's total population lives in these three Rice's Point Boat Landing Point neighborhoods. Data Source: Minnesota Population Center. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0 ± Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota 2011. -

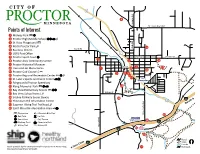

Proctor Recreation

It’s way cooler up the hill There are lots of trains here Proctor: We're just outside of Duluth Where fog is thick as soup Built by resilient, hard-working people C I T Y O F 2 4 the Hoghead is Home is where MINNESOTA St. Louis River Rd Points of Interest 1 Midway Park 2 Proctor High/Middle School e 3 St. Rose Playground v A d 4 North Proctor Park n 2nd Ave2 Ave14 Rd Lavaque Proctor: The city on the hill Proctor: Stark Rd 5 Business District 6 2 USPS Post Office 7 55thth StSt VinlandVinland StSt Proctor Sport Court Li 1 8 Proctor Area Community Center 5 16 � le town with a big heart le town 9 Proctor Historical Museum 2nd2nd StSt 7 10 Train and Jet Monuments 2 6 17 15 11 Proctor Golf Course 3 8 9 12 Proctor Regional Recrea�on Center 10 11 13 St. Luke's Sports and Event Center 14 Fairgrounds/Proctor Speedway 15 Klang Memorial Park 12 16 Bay View Elementary School Kirkus St 17 Bay View School Forest A community built by the railroad the railroad built by A community The city up in the clouds 18 Skyline Parkway Scenic Byway 13 35 19 Thompson Hill Informa�on Center 2 20 Superior Hiking Trail Trailhead Duluth→ 21 Spirit Mountain Recrea�on Area Playground Mountain Bike Trail Boundary Ave 19 Ball Field Ice Rink Sport Court Golf Course 18 Walking Track Adventure Park 35 Hiking Trail Sliding Hill Ugstad Rd Ugstad 35 A city with a town A city with a town Three square miles of can do miles of can square Three 20 Roads 35 Trails Creeks Made possible by the Statewide Health Improvement Partnership, 21 Railroads the hour Minnesota Department -

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV Maps and Descriptions Denis White March 2020

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV maps and descriptions Denis White March 2020 (Image NOAA, Landsat, Copernicus; Presentation Google Earth) A contribution to the corpus of materials created by James Omernik and colleagues on the Ecological Regions of the United States, North America, and South America The page size for this document is 9 inches horizontal by 12 inches vertical. Table of Contents Content Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Geographic patterns in Minnesota 1 Geographic location and notable features 1 Climate 1 Elevation and topographic form, and physiography 2 Geology 2 Soils 3 Presettlement vegetation 3 Land use and land cover 4 Lakes, rivers, and watersheds; water quality 4 Flora and fauna 4 3. Methods of geographic regionalization 5 4. Development of Level IV ecoregions 6 5. Descriptions of Level III and Level IV ecoregions 7 46. Northern Glaciated Plains 8 46e. Tewaukon/BigStone Stagnation Moraine 8 46k. Prairie Coteau 8 46l. Prairie Coteau Escarpment 8 46m. Big Sioux Basin 8 46o. Minnesota River Prairie 9 47. Western Corn Belt Plains 9 47a. Loess Prairies 9 47b. Des Moines Lobe 9 47c. Eastern Iowa and Minnesota Drift Plains 9 47g. Lower St. Croix and Vermillion Valleys 10 48. Lake Agassiz Plain 10 48a. Glacial Lake Agassiz Basin 10 48b. Beach Ridges and Sand Deltas 10 48d. Lake Agassiz Plains 10 49. Northern Minnesota Wetlands 11 49a. Peatlands 11 49b. Forested Lake Plains 11 50. Northern Lakes and Forests 11 50a. Lake Superior Clay Plain 12 50b. Minnesota/Wisconsin Upland Till Plain 12 50m. Mesabi Range 12 50n. Boundary Lakes and Hills 12 50o. -

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Existing Conditions Summary February 2021

Comprehensive Operations Analysis Existing Conditions Summary February 2021 Presented to Duluth Transit Authority Prepared by Connetics Transportation Group 1.0 Introduction In August 2020, the Duluth Transit Authority (DTA) engaged Connetics Transportation Group (CTG) to conduct a Comprehensive Operations Analysis (COA) of their fixed-route transit system. This technical memorandum presents the methodology and findings of the existing conditions analysis for the COA. The COA is structured around five distinct phases, with the existing conditions analysis representing Phase 2 of the process. The following outlines each anticipated phase of the COA with corresponding objectives: Phase 1 Guiding Principles: Determines the elements and strategies that guide the COA process. Phase 2 Existing Conditions: Review and assess the regional markets and existing DTA service. Phase 3 Identify and Evaluate Alternatives: Create service delivery concepts for the future DTA network. Phase 4 Finalize Recommended Network: Select a final recommended network for implementation. Phase 5 Implementation and Scheduling Plan: Create a plan to executive service changes and implement the recommended network. The DTA provides transit service to the Twin Ports region, primarily in and around the cities of Duluth, Minnesota and Superior, Wisconsin. In August 2020, CTG worked with DTA staff and members of a technical advisory group (TAG) to complete Phase 1 of the COA (Guiding Principles). This phase helped inform CTG of the DTA and TAG member expectations for the COA process and desired outcomes of the study. They expect the COA process to result in a network that efficiently deploys resources and receives buy-in from the community. The desired outcomes include a recommended transit network that is attractive to Twin Port’s residents, improves the passenger experience, improves access to opportunity, is equitable, is resilient, and is easy to scale when opportunity arises. -

2001 Truck Route Study

Duluth-Superior Area Study $ # $ $$ $ # # # # # # # # â 1 â3 $ # 15 $ # $ # $ $ â # $ # 16 # $ $ â $ #$ $ # 7 $ $ # # $$ 14 $ â $ # $ $ $ # $ # $ â # $#$# # $ # $$ ## # #$ 8 # # # # â# # # # # #$# # # # # # $# ## #$$ # $$# # $ # # ### 9 #### # # # # ## # # # â #$$ #$#$ # # # ## $$ #### $ $$## $ #$$## $ $ #$ ## #$$ ##$$#$# ## $$$ $ ### $ $$$ ## #$# $ # ### $ ## $$# # # $$#$## # # $$ $# $ $ $ # ######## $# #$# $ #13 # 5 ## #######$####$# # # $$ # $ $ 6 #$###$#####$$## #$ # # # #â#### â ## ##$ $###11# $ â # $$ # ## ### ## $# # ##$ â# $ # 4 # ####### # # # ## #####$########## # # # ###### ## ######## ## â # ## # # 2 $ # # # $# # # # ### ## # # # â # ##### # # ### # # $ $ # $ $## $# # # # $ $ # $ # # # # # ## $ $ ## $# # $ # # 12# # $ # # â # # $ â10 Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Committee Approved April 18, 2001 Duluth-Superior Truck Route Study Approved April 18, 2001 Prepared by the Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Committee Duluth Superior urban area communities cooperating in planning and development through a joint venture of the Arrowhead Regional Development Commission and the Northwest Regional Planning Commission This study was funded through the Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Committee with funding from the: Federal Highway Administration Minnesota Department of Transportation Wisconsin Department of Transportation Arrowhead Regional Development Commission Northwest Regional Planning Commission Copies of the study are available from the Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Committee 221 West 1st Street, -

2019 7:00 PM Council Chamber

411 West First Street City of Duluth Duluth, Minnesota 55802 Minutes - Final City Council MISSION STATEMENT: The mission of the Duluth City Council is to develop effective public policy rooted in citizen involvement that results in excellent municipal services and creates a thriving community prepared for the challenges of the future. TOOLS OF CIVILITY: The Duluth City Council promotes the use and adherence of the tools of civility in conducting the business of the council. The tools of civility provide increased opportunities for civil discourse leading to positive resolutions for the issues that face our city. We know that when we have civility, we get civic engagement, and because we can’t make each other civil and we can only work on ourselves, we state that today I will: pay attention, listen, be inclusive, not gossip, show respect, seek common ground, repair damaged relationships, use constructive language, and take responsibility. [Approved by the council on May 14, 2018] Monday, January 14, 2019 7:00 PM Council Chamber ROLL CALL Present: 8 - Councilor Gary Anderson, Councilor Zack Filipovich, Councilor Jay Fosle, Councilor Barb Russ, Councilor Joel Sipress, Councilor Em Westerlund, Councilor Renee Van Nett and President Noah Hobbs PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ELECTION OF OFFICERS PUBLIC HEARING: State Project No. 6982-328, Local Road Improvements on 46th Avenue West, 27th Avenue West, Garfield Avenue and Railroad Street for the Twin Ports Interchange Project REPORTS FROM THE ADMINISTRATION REPORTS FROM OTHER OFFICERS 1. 19-008 MN Department of Health, Quarterly Report Indexes: Attachments: MN Department of Health, Quarterly Report This Informational Report was received. -

The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: an Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 1 1976 The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J. Sheran Timothy J. Baland Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Sheran, Robert J. and Baland, Timothy J. (1976) "The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol2/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Sheran and Baland: The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An THE LAW, COURTS, AND LAWYERS IN THE FRONTIER DAYS OF MINNESOTA: AN INFORMAL LEGAL HISTORY OF THE YEARS 1835 TO 1865* By ROBERT J. SHERANt Chief Justice, Minnesota Supreme Court and Timothy J. Balandtt In this article Chief Justice Sheran and Mr. Baland trace the early history of the legal system in Minnesota. The formative years of the Minnesota court system and the individuals and events which shaped them are discussed with an eye towards the lasting contributionswhich they made to the system of today in this, our Bicentennialyear. -

What Happened to the Settlers in Renville County?

What Happened to the Settlers in Renville County? Family and Friends of Dakota Uprising Victims What Happened to the Settlers in Renville County? The Aftermath of the U.S. - Dakota War Janet R. Clasen Klein - Joyce A. Clasen Kloncz Volume II 2014 What Happened to the Settlers in Renville County? “With our going, the horrors of August, 1862 will cease to be a memory. Soon it will just be history – history classed with the many hardships of frontier life out of which have grown our beautiful, thriving state and its good, sturdy people. .” Minnie Mathews, daughter of Werner Boesch From the Marshall Daily Messenger, 1939 Front cover, ‘People Escaping the Indian Massacre. Dinner on the Prairie. Thursday, August 21st, 1862’, by Adrian Ebell and Edwin Lawton, photographers. Joel E. Whitney Gallery, St. Paul, Minnesota, publisher. Ebell photographed the large group of settlers, missionaries, Yellow Medicine Indian Agency employees and Dakota escaping with him and Mr. Lawton. This image is thought to be the only image photographed during the war. The photograph was probably taken in the general vicinity of Morton in Renville County but up on the highlands. We are grateful to Corinne L. Marz for the use of this photograph from the Monjeau-Marz Collection. What Happened to the Settlers in Renville County? Our group Family and Friends of Dakota Uprising Victims was founded in 2011 to recognize our settler ancestors and honor their sacrifice and place in Minnesota history. On August 18, 1862, many settlers lost their lives, their homes, their property and peace of heart and mind. -

Legislative Brief

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 2 I. PLAINTIFFS' LEGISLATIVE REDISTRICTING PLAN ACCURATELY REFLECTS THE CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS OF THE STATE .......................................................... 2 A. Legislative Maps Should Begin with Logical Groupings of Counties and Cities Where Possible ................................................. 2 B. House Districts Should Be Drawn Before Senate Districts .............. 3 C. Districts Should Use Rivers as Natural Boundary Lines .................. 5 D. Townships Should Be Paired With Their Related Cities or Towns Whenever Possible ................................................................ 5 II. PLAINTIFFS' LEGISLATIVE REDISTRICTING PLAN BENEFITTED FROM PUBLIC COMMENT AND LEGISLATIVE EXPERTISE ................................................................................................. 6 ARGUMENT ...................................................................................................................... 9 I. PLAINTIFFS' PROPOSED LEGISLATIVE DISTRICTS SATISFY CONSTITUTIONAL REQUIREMENTS ................................................... 9 A. The Proposed Legislative Districts Satisfy the Panel's Population Equality Requirements .................................................... 9 1. House District 26A .............................................................. -

Around a Geologic Clock in Minnesota

MINNESOTA HISTORY A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE VOLUME 15 JUNE, 1934 NUMBER 2 AROUND A GEOLOGIC CLOCK IN MINNESOTA^ Before anyone can understand the geological history of a region, two fundamental geological concepts must be thoroughly comprehended. These are the magnitude of geological time and the enormous gaps in the geological record of any one region. To quickly gain an appreciation of the enormous number of years Involved in reviewing the events of the past that have been recorded In the rocks of Minnesota, let us imag ine that all the events in the geologic history of our state since the formation of the earliest known rocks are to be portrayed before our eyes on an enormous motion picture screen during one revolution of the hour hand on a clock. Twelve hours on our imaginary clock will then represent at least five hundred million years In the geologic history of our state. Each hour will represent over forty million years; each minute, seven hundred thousand years; each second, as it ticks by, will see eleven thousand, six hundred years in the geologic history of Minnesota move past us in review. On this clock of ours, the entire history of man on the earth will occupy less than a minute, and one-fifth of a second will serve for all the period recorded in the history of civilized man. On our earth, mountains have been born where once the 'A radio talk presented over the University of Minnesota station WLB under the auspices of the Minnesota Historical Society on April 3. Ed. 141 142 LOUIS H. -

City of Duluth 2016 Housing Indicator Report

City of Duluth 2016 Housing Indicator Report Prepared by: Released: June 2018 Community Planning Division City Hall Room 208 Duluth, MN 55802 http://www.duluthmn.gov/community-planning/ Executive Summary Purpose The Community Planning Division publishes the Housing Indicator Report annually to provide a snapshot of the current housing markets and to understand how those markets have changed over time. We include demographic and workforce statistics to provide context about what kinds of housing options are available and affordable to a diverse range of our community members. Key Findings Average and median home sale price have gradually increased over the past decade and while homeowners’ median household income seems to have stagnated in the past few years, average homeownership costs still appear to be affordable to middle income homeowners. From 2014 to 2015 the average market rent increased drastically by almost $100 a month and while it continued to increase in 2016 to $920, it was a less drastic increase than in the previous year. Average market rate rental housing has not been affordable to the majority of renter households for at least a decade and that trend continues in 2016. This year we focused on some of the systemic issues that contributed to creating the disparities and the wealth gap we see between the higher and lower income neighborhoods in our city. With a better understanding of these disparities and their causes, there can be more informed decisions made about the allocation of services and resources. Examining these historical disparities also provides more context and insight to our housing market. -

City of Duluth Duluth, Minnesota 55802

PC Packet 01-12-2021 411 West First Street City of Duluth Duluth, Minnesota 55802 Meeting Agenda Planning Commission. Tuesday, January 12, 2021 5:00 PM Council Chamber, Third Floor, City Hall, 411 West First Street To view the meeting, visit http://www.duluthmn.gov/live-meeting Call to Order and Roll Call Public Comment on Items Not on Agenda Approval of Planning Commission Minutes PL 20-1208 Minutes 12/8/20 Consent Agenda PL 20-185 Variance to Side and Front Yard Setbacks to Match Existing Foundation at 2001 W 8th Street by Kurt Herke PL 20-189 Interim Use Permit for a Vacation Dwelling Unit at 7 N 19th Avenue W, Unit 1, by Newcastle 8 LLC PL 20-190 Interim Use Permit for a Vacation Dwelling Unit at 7 N 19th Avenue W, Unit 2, by Newcastle 8 LLC PL 20-191 Interim Use Permit for a Vacation Dwelling Unit at 7 N 19th Avenue W, Unit 3, by Newcastle 8 LLC PL 20-192 Interim Use Permit for a Vacation Dwelling Unit at 7 N 19th Avenue W, Unit 4, by Newcastle 8 LLC Public Hearings PL 20-194 Variance to Off-Street Parking Requirements at 310 N 9th Avenue E by Beverly Ricker Communications - Land Use Supervisor Report - Historic Preservation Commission Report - Joint Airport Zoning Board Report City of Duluth Page 1 Printed on 1/4/2021 Page 1 of 78 PC Packet 01-12-2021 Planning Commission. Meeting Agenda January 12, 2021 - Duluth Midway Joint Powers Zoning Board Report NOTICE: The Duluth Planning Commission will be holding its January 12, 2021 Special Meeting by other electronic means pursuant to Minnesota Statutes Section 13D.021 in response to the COVID-19 emergency.