Who Writes the Rules of E-Commerce? a Case Study of the Global Business Dialogue on E-Commerce (Gbde) Maria Green Cowles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings - Global Forum 2006 P 2 9 & 10 November 2006 in Paris, France – © ITEMS International 2006

CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 3 Programme................................................................................................................. 5 About the Global Forum ........................................................................................... 15 Think Tank Synthesis Report.................................................................................... 16 Contact ....................................................................................................................124 Acronyms & Abbreviations.......................................................................................125 Report written by Susanne Siebald, Communications Consultant assisted by Tema Best, Politech Institute Proceedings - Global Forum 2006 p 2 9 & 10 November 2006 in Paris, France – © ITEMS International 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am pleased to make these proceedings available and to have the occasion to address a few words of thanks. The Global Forum 2006 on 9 & 10 November in Paris brought together the expertise of more than 300 high-profile representatives from across political, business, and academic institutions and represented more than 30 countries. Having done our very best to create a warm and enjoyable atmosphere during the Forum for people to get and to work together, I sincerely hope that the Global Forum 2006 will result in new partnerships, collaborations and other valuable contacts being established. An event -

Anuario Sobre La Acción Exterior De Euskadi 2005

ANUARIO SOBRE LA ACCIÓN EXTERIOR DE EUSKADI 2005 José Luis DE CASTRO RUANO Alexander UGALDE ZUBIRI Profesor Titular de Derecho Constitucional Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea Erakunde Autonomiaduna Organismo Autónomo del Oñati, 2006 AAnuarionuario AAcccc EExtxt 2005.indd2005.indd 3 228/8/068/8/06 111:22:201:22:20 © Administración de la Comunidad Autónoma de Euskadi Euskadiko Autonomia Elkarteko Administrazioa Edita: Instituto Vasco de Administración Pública Herri-Arduralaritzaren Euskal Erakundea ISSN: 1887-0163 Depósito Legal: BI-2658--06 Fotocomposición: Ipar, S. Coop., Zurbaran, 2-4 - 48007 Bilbao Imprime: RGM, S.A., Padre Larramendi, 2 - 48012 Bilbao AAnuarionuario AAcccc EExtxt 2005.indd2005.indd 4 225/10/065/10/06 009:51:389:51:38 Iñaki Aguirre Zabalari, adiskide eta lagun onari AAnuarionuario AAcccc EExtxt 2005.indd2005.indd 5 55/9/06/9/06 113:21:383:21:38 AAnuarionuario AAcccc EExtxt 2005.indd2005.indd 6 228/8/068/8/06 111:22:211:22:21 Índice 1. Introducción. 11 1.1. Balance de la acción exterior de 2005 . 11 2. Participación de Euskadi en la Unión Europea . 17 2.1. Introducción . 17 2.2. El euskera en la Unión Europea . 20 2.3. La concertación multilateral intraestatal: aplicación de los Acuer- dos de 9 de diciembre de 2004 . 24 2.3.1. Las Conferencias Sectoriales y la Conferencia para Asuntos Relacionados con las Comunidades Europeas (CARCE) . 24 2.3.2. La participación de Euskadi en el Consejo de Ministros de la UE. 25 2.3.3. La Consejería autonómica de la Representación Perma- nente . 30 2.4. Participación de Euskadi en el Comité de las Regiones . -

Comparative Study of Smart Cities in Europe and China

EU-China Smart and Green City Cooperation Comparative Study of Smart Cities in Europe and China prepared for Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) DG CNECT, EU Commission with China Academy of Telecommunications Research (CATR) June 2014 1 Authors Chinese expert team: EU expert team: Kang Yanrong, Zang Lei, Chen Cai, Ge Jeanette Whyte Yuming, Li Hao, Cui Ying Thomas Hart Acknowledgements This report and the related White Paper on the “Comparative Study of Smart Cities in Europe and China” was commissioned by the EU Policy Dialogue Support Facility II (PDSF) and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China (MIIT). The Chinese expert team was led by Dr Kang Yanrong of the Chinese Academy of Telecommunications Research (CATR) at the Ministry for Industry and Information Technology (MIIT). The European expert team was led by Jeanette Whyte of Jenesis Consulting. The authors would like to express their gratitude to all those who supported and facilitated the work on these documents, in particular: The participating cities contributed greatly in providing background information on their smart city projects and gave their time generously in completing the Smart City Assessment Framework. Dr. Qin Hai, Director-General of the Department of ICT Development and Application in MIIT, who gave strong support to the project and provided the preface to this White Paper. Mr. Yu Xiaohui, Chief Engineer of CATR, group leader of the Chinese Technical Expert Group who supervised the work of the Chinese expert team. Dr Shaun Topham who liaised with the European cities and the project and gathered relevant information on smart city projects as input for the analysis. -

Propuesta Para El Fortalecimiento De La Gestión De La Cooperación Internacional En

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE COSTA RICA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES ESCUELA DE RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES PROPUESTA PARA EL FORTALECIMIENTO DE LA GESTIÓN DE LA COOPERACIÓN INTERNACIONAL EN LA MUNICIPALIDAD DE ESPARZA DOUGLAS ENRIQUE SALAZAR CORTÉS Proyecto de Graduación sometido a consideración del Tribunal Examinador para optar por el grado de Magíster Scientiae en Relaciones Internacionales y Diplomacia con énfasis en Administración de Proyectos de Cooperación. Heredia, Costa Rica Noviembre, 2015 DEDICATORIA A mis padres, Luis Antonio Salazar Badilla Esmeralda Cortés Rojas Por su valentía y perseverancia para sacar adelante nuestra familia. ii AGRADECIMIENTO A Dios por darme el don de la vida y la oportunidad de superarme día con día, y la fortaleza necesaria para hacer frente a las adversidades que se nos presentan en el camino. A Carlos Murillo Zamora, Fernando Ocampo Sánchez, Francisco Flores Zúñiga y Rafael Sánchez Meza, más que profesores fueron maestros de vida, por su apoyo y motivación durante mis años de estudio. A Miguel Ángel Rodríguez Echeverría, Rodolfo Piza Rocafort y Óscar Arias Sánchez por ser fuente de inspiración en mis objetivos personales y profesionales. A Juan Carlos Méndez Barquero y a Orlando Vega Cano por su apoyo y colaboración en la etapa final de mis estudios de posgrado. iii PENSAMIENTO “No es vanidad creer que uno puede cambiar el curso de la historia.” Dr. Óscar Arias Sánchez Premio Nobel de la Paz Presidente de la República de Costa Rica en 1986 – 1990 y 2006 – 2010 iv PROPUESTA PARA EL FORTALECIMIENTO DE LA GESTIÓN DE LA COOPERACIÓN INTERNACIONAL EN LA MUNICIPALIDAD DE ESPARZA Proyecto de Graduación del Programa de Maestría en Relaciones Internacionales y Diplomacia con énfasis en Administración de Proyectos de Cooperación. -

Panel Discussion: "Telematics Tools in The

TELEMATICS TOOLS IN THE ENVIRONMENT SECTOR: THE REAL CONTRIBUTION TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Panel Discussion: “Telematics Tools in the Environment Sector: The Real Contribution to Sustainable Development” Panel Chair: Siegfried Rupprecht: Rupprecht Consult-Forschung und Beratung GmbH, Cologne DE; Technical Co-ordinator of the CAPE Project, Panel members: Nick Hodges: Leicester City Council; Leicester, UK; Special Project Officer in charge for Transport and Environment Project on European and National Levels, Memeber of the ENWAP expert group Joachim Lorenz: City of Munich, Munich, DE; Top civil servant responsible for Environment and Health issues in the City of Munich, Violeta Kauneliene: Environmental Center of Administration and Technology, Vilnius, LT; The Environmental Center of Administration and Technology is a NGO in Lithuania, supporting the Development Implementation of Environmental Projects in municipalities; Franz Jungwirth: Bavarian State Ministry for Development, Bavaria, DE; Especially in charge for the regional Bavarian Development programme, in the area of air quality Franz Josef Radermacher: Director of the FAW (Research Institute for Applied Knowledge Proc- essing), Ulm, DE; Steering committee member of the Information Society Forum of the European Commission João Ribeiro da Costa: University of Lisbon, Lisbon PT; Frequently involved in Environmental Programmes on European and national levels, member of the ENWAP expert group The discus- sion reflects general statements from a vari- ety of back- grounds and perspectives with state- ments con- cerning local, regional, European, and global levels. The following documenta- tion offers a complete re- cord of the panel discussion. The original recording can be found as real audio streams on the Internet at the fol- lowing address: http://www.isep.at/conferences/. -

Proceedings - Global Forum 2005 P 2 7 & 8 November 2005 in Brussels, Belgium – © ITEMS International 2005

CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 3 Programme................................................................................................................. 5 About the Global Forum ........................................................................................... 13 Think Tank Synthesis Report.................................................................................... 14 Contact ....................................................................................................................138 Acronyms & Abbreviations.......................................................................................139 Annex 1: Press Review............................................................................................141 Report written by Susanne Siebald, Communications Consultant assisted by Tema Best, Politech Institute Proceedings - Global Forum 2005 p 2 7 & 8 November 2005 in Brussels, Belgium – © ITEMS International 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The conference is over and more than 300 high-profile delegates from more than 30 different countries attended the conference sessions which took place on 7 & 8 November in the historical Palais d’Egmont in Brussels. When looking back on fourteen years of successful networking, it seems to us, that such an historical place represents a fantastic environment for the Global Forum, which brings together - each year - so many different industry and political leaders, organisations, countries, -

Guidelines for the International Relations of Local Governments and Decentralised Cooperation Between the European Union and Latin America

Guidelines for the international relations of local governments and decentralised cooperation between the European Union and Latin America VOLUME 1 Practical Manual for the internationalisation of Cities Author: Eugene D. Zapata Garesché 3 © Diputación de Barcelona, 2007 All rights reserved. 4 General contents Tables 8 Acronyms 11 Institutional Presentation 14 Foreword 16 1. Why should local government implement international action? 18 1.1. The context is favourable 18 1.2. Local government in the world: from observer to leading actor 24 2. How to devise an effective, long-term strategy? 31 2.1. Drawing up the strategy 33 2.1.1. Assessing the external context 33 2.1.2. Analysing the internal situation 33 w34 2.1.3. Identifying local priorities 2.1.4. Defining a vision for the future 35 2.2. Implementing the strategy 39 2.2.1. Verifying the legality of actions 41 2.2.2. Adapting the institution and its procedures 49 2.2.3. Allocating resources 51 5 2.3. Professionalising the strategy 56 2.3.1. Formalising and ensuring continuity 56 2.3.2. Communicating and raising awareness 60 2.3.3. Evaluating and perfecting the strategy 65 3. Who are involved in a local government’s internationalisation process? 68 3.1. Mechanisms for participation and concertation 69 3.2. Citizen and community groups 73 3.3. Universities 74 3.4. The business sector 76 3.5. Non-governmental organisations 77 3.6. Other local governments 78 4. How to provide the city with visibility and international projection? 81 4.1. Economic promotion: investments, foreign trade and tourism 84 4.2. -

Connecting Businesses & Communities

Connecting Businesses & Communities Information and Communication Technology Strategies in an Emerging Knowledge based Economy & Society ROME – ITALY PALAZZO TAVERNA 6TH & 7TH NOVEMBER, 2003 - PROCEEDINGS - Organized by CONTENTS Acknowledgements..................................................................................................... 3 Programme................................................................................................................. 5 About the Global Forum............................................................................................ 12 Think Tank Synthesis Report.................................................................................... 13 Contact ..................................................................................................................... 85 List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................. 86 Annex: Press Review................................................................................................ 88 Report written by Susanne Siebald, Communication Consultant, assisted by Myriam El Hadj Ali, Items International Proceedings - Global Forum 2003 p 2 6 & 7 November 2003 in Rome - Italy – ITEMS International ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS After Washington, New York, Rome, Paris, Kyoto, San Francisco, Silicon Valley, Sophia- Antipolis and Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the Global Forum returned to Rome on 6 & 7 November 2003. The conference is over and 312 delegates from 28 different countries attended the -

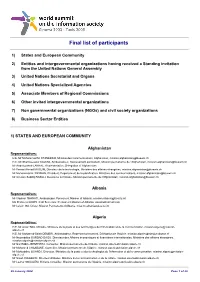

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies -

Worlding Cities

WORLDING CITIES RRoy_ffirs.inddoy_ffirs.indd i 55/7/2011/7/2011 112:44:042:44:04 PPMM Studies in Urban and Social Change Published Cities after Socialism: Urban and Regional Change and The Creative Capital of Cities: Interactive Knowledge Conflict in Post-Socialist Societies of Creation and the Urbanization Economics of Gregory Andrusz, Michael Harloe and Ivan Innovation Szelenyi (eds.) Stefan Krätke The People’s Home? Social Rented Housing in Europe Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of and America Being Global Michael Harloe Ananya Roy and Aihwa Ong (eds.) Post-Fordism Place, Exclusion, and Mortgage Markets Ash Amin (ed.) Manuel B. Aalbers The Resources of Poverty: Women and Survival in a Working Bodies: Interactive Service Employment and Mexican City* Workplace Identities Mercedes Gonzalez de la Rocha Linda McDowell Free Markets and Food Riots Networked Disease: Emerging Infections in the Global City John Walton and David Seddon S. Harris Ali and Roger Keil (eds.) Fragmented Societies* Eurostars and Eurocities: Free Movement and Mobility Enzo Mingione in an Integrating Europe Urban Poverty and the Underclass: A Reader* Adrian Favell Enzo Mingione Urban China in Transition John R. Logan (ed.) Forthcoming Getting Into Local Power: The Politics of Ethnic Locating Neoliberalism in East Asia: Neoliberalizing Minorities in British and French Cities Spaces in Developmental States Romain Garbaye Bae-Gyoon Park, Richard Child Hill and Asato Saito (eds.) Cities of Europe Yuri Kazepov (ed.) Subprime Cities: The Political Economy of Mortgage Markets Cities, War, and Terrorism Manuel B. Aalbers (ed.) Stephen Graham (ed.) Globalising European Urban Bourgeoisies?: Rooted Cities and Visitors: Regulating Tourists, Markets, and Middle Classes and Partial Exit in Paris, Lyon, City Space Madrid and Milan Lily M. -

Sustainable Cities for the Third Millennium: the Odyssey of Urban Excellence

Sustainable Cities for the Third Millennium: The Odyssey of Urban Excellence Voula P. Mega Sustainable Cities for the Third Millennium: The Odyssey of Urban Excellence Voula P. Mega, after a special authorisation by the European Commission PhD in City & Regional Policy and Planning Brussels Belgium [email protected] [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-6036-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-6037-5 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-6037-5 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Library of Congress Control Number: 2010934906 © Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. The publisher makes no warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein. -

Policy Deueiopment and Lobbying with the European Institutions

Gemeente Den Haag Retouradres: Postbus 12 600,2500 DJ Den Haag Uw brief van de gemeenteraad Uw kenmerk Ons kenmerk rm 13/BSD RIS 093677 Doorklesnummer (070) 353 2710 Aantal bijlagen Datum Onderweip 5 februari 2002 Jaarvergadering Telecities 10-12 december 2001 Hierbij informeren wij u over de Telecities-conferentie 'Citizens at the heart of democratie renewal: change management in cities', gehouden te Marseille van 10 tot en met 12 december 2001. Den Haag is wederom verkozen in het Steering Committee van Telecities, een netwerk van Europese steden op gebied van stedelijke ICT-projecten en beleid. Sinds het begin van Telecities in 1994 is Den Haag als mede-oprichter vertegenwoordigd in dit bestuur door de wethouder Informatiebeleid. In de periode 1996 - 1998 als voorzitter, vanaf 1999 als lid. Werkplan voor het jaar 2002 Tijdens de jaarvergadering is het Werk Programma 2002 besproken. Belangrijkste verandering met het jaar 2001 is dat de werkzaamheden van Telecities als geheel maar ook van de werkgroepen beter afgestemd worden op de voorstellen van de Europese Commissie (EC) in het Zesde Kaderprogramma. Dit Zesde Kaderprogramma opereert op verschillende gebieden zoals biotechnologie en kennismaat- schappij. Interessant voor Telecities en Den Haag is het onderdeel 'hiformation Society Technology' (1ST). In het IST-programma is in de komende jaren een budget van 3,6 miljard Euro ter beschikking voor ingediende projectvoorstellen. Teneinde zulke voorstellen te doen zijn de werkgroepen van Telecities afgestemd op de belangrijkste onderdelen van het IST-programma. Bedoeling van deze koppeling van de onderwerpen van de werkgroepen en de lijnen van de EC is dat het eenvoudiger wordt projectvoorstellen in te dienen en tevens via het netwerken invloed uit te oefenen op project- en beleidsvoorstellen.