Geoff Dyer Now We Can

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Initial Coin Offerings

BRAINY IAS Year End Review- 2017: Ministry of I&B The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, which is entrusted with the responsibility to Inform, Educate and Entertain the masses, took various initiatives in the last one year to attain its objectives. The Information sector witnessed a plethora of initiatives in the form of International cooperation with Ethiopia, devising 360 degree multimedia campaigns, release of RNI annual report on Press in India, etc. Similarly, the Films sector witnessed successful completion of the 48th IFFI and the Broadcasting sector witnessed the launch of 24x7 DD Channel for Jharkhand. The Initiatives of Ministry in different sectors are mentioned below: Information Sector Agreement on “Cooperation in the field of Information, Communication and Media” was signed between India and Ethiopia. The Agreement will encourage cooperation between mass media tools such as radio, print media, TV, social media etc. to provide more opportunities to the people of both the nations and create public accountability. 6th National Photography Awards organized. Shri Raghu Rai conferred Lifetime Achievement Award. Professional Photographer of the year award to Shri K.K. Mustafah and Amateur Photographer of the year award to Shri Ravinder Kumar. Three Heritage Books on the occasion of Centenary Celebrations of Champaran Satyagraha released. Set of books titled ‘Swachh Jungle ki kahani – Dadi ki Zubani’ Books published in 15 Indian languages by Publications Division to enable development of cleanliness habit amongst children released. “Saath Hai Vishwaas Hai, Ho Raha Vikas Hai” Exhibition organized and was put up across state capitals for duration of 5-7 days showcasing the achievements of the Government in the last 3 years in various sectors. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-19605-6 — Boundaries of Belonging Sarah Ansari , William Gould Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-19605-6 — Boundaries of Belonging Sarah Ansari , William Gould Index More Information Index 18th Amendment, 280 All-India Muslim Ladies’ Conference, 183 All-India Radio, 159 Aam Aadmi (Ordinary Man) Party, 273 All-India Refugee Association, 87–88 abducted women, 1–2, 12, 202, 204, 206 All-India Refugee Conference, 88 abwab, 251 All-India Save the Children Committee, Acid Control and Acid Crime Prevention 200–201 Act, 2011, 279 All-India Scheduled Castes Federation, 241 Adityanath, Yogi, 281 All-India Women’s Conference, 183–185, adivasis, 9, 200, 239, 261, 263, 266–267, 190–191, 193–202 286 All-India Women’s Food Council, 128 Administration of Evacuee Property Act, All-Pakistan Barbers’ Association, 120 1950, 93 All-Pakistan Confederation of Labour, 256 Administration of Evacuee Property All-Pakistan Joint Refugees Council, 78 Amendment Bill, 1952, 93 All-Pakistan Minorities Alliance, 269 Administration of Evacuee Property Bill, All-Pakistan Women’s Association 1950, 230 (APWA), 121, 202–203, 208–210, administrative officers, 47, 49–50, 69, 101, 212, 214, 218, 276 122, 173, 176, 196, 237, 252 Alwa, Arshia, 215 suspicions surrounding, 99–101 Ambedkar, B.R., 159, 185, 198, 240, 246, affirmative action, 265 257, 262, 267 Aga Khan, 212 Anandpur Sahib, 1–2 Agra, 128, 187, 233 Andhra Pradesh, 161, 195 Ahmad, Iqbal, 233 Anjuman Muhajir Khawateen, 218 Ahmad, Maulana Bashir, 233 Anjuman-i Khawateen-i Islam, 183 Ahmadis, 210, 268 Anjuman-i Tahafuuz Huqooq-i Niswan, Ahmed, Begum Anwar Ghulam, 212–213, 216 215, 220 -

Please Scroll Down for Article

This article was downloaded by: [Sternberger, Paul] On: 26 February 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 909051291] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Photographies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t778749997 ME, MYSELF AND INDIA Paul Sternberger Online Publication Date: 01 March 2009 To cite this Article Sternberger, Paul(2009)'ME, MYSELF AND INDIA',Photographies,2:1,37 — 58 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/17540760802696971 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17540760802696971 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Paul Sternberger ME, MYSELF AND INDIA Contemporary Indian photography and the diasporic experience Recent Indian photographers have used their medium to reveal, interpret, and influence the multifaceted nature of Indian identity and cross-cultural experiences in India and abroad. -

Slum Free City Plan of Action - Allahabad

Slum Free City Plan of Action - Allahabad Regional Centre for Urban and Environmental Studies (Sponsored by Ministry of Urban Development, Govt. of India) Osmania University, Hyderabad - 500007 [SLUM FREE CITY PLAN OF ACTION] Allahabad CONTENTS CONTENTS............................................................................................................................................ i LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF CHARTS ............................................................................................................................... v LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................................. v LIST OF PICTURES ........................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF MAPS................................................................................................................................... vii ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................... viii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. xi ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ................................................................................................................. xiii CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION -

Miscellaneous Questions

Downloaded from http://SmartPrep.in Miscellaneous 1. Match List-I with List-II and select the correct 4. Consider the following statements : answer from the codes given below : 1. Lord Clive was the first Governor of List-I List-II Bengal. A. Labour’s Day 1. May 31st 2. G.V. Mavlankar was the first speaker of Lok B. Anti-Tobacco Day 2. May 2nd Sabha. C. Mother’s Day 3. May 1st 3. Dr. Zakir Hussain was the first Muslim D. National Girl Child 4. Jan 24th President of Indian Republic. Codes: 4. Rakesh Sharma was the first Indian Cosmonaut. A B C D A B C D Which of the statements given above is/are (a) 1 2 3 4 (b) 3 1 2 4 correct? (c) 1 3 2 1 (d) 4 3 2 1 (a) 1 and 2 only (b) 2 and 3 only 2. Match List-I with List-II and select the correct (c) 1, 2 and 3 only (d) All of the above answer from the codes given below : 5. Match List-I with List-II and select the correct List-I List-II answer from the codes given below : (Folk Dance) (State) List-I List-II A. Bidesia 1. Jharkhand A. The largest lake 1. Jammu and Kashmir B. Lajri 2. Uttarakhand B. The largest delta 2. Sunderbans C. Dangri 3. Himachal Pradesh (Kolkata) D. Tamasha 4. Mahrashtra C. The largest 3. Birla Planetarium Codes: planetarium (Kolkata) A B C D A B C D D. The highest 4. Leh (Ladakh) (a) 1 2 3 4 (b) 1 3 4 2 airport (c) 3 1 2 4 (d) 3 1 4 2 Codes: 3. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

Museum Bhavan Guide

MUSEUM BHAVAN GUIDE “Museum Bhavan is a living exhibition that will wax and wane with the lunar cycle.” Dayanita Singh This is the premiere of MUSEUM BHAVAN on its home ground — at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, Delhi, it becomes a museum within a museum. MUSEUM BHAVAN is a collection of museums made by Dayanita Singh. They have previously been shown in London, Frankfurt and Chicago, and here, in Delhi, the artist has installed nine museums from the collection. Each holds old and new images, from the time Singh began photography in 1981 until the present. The architecture of the museums is integral to the realization of the images shown and stored in them. Each structure can be placed and opened out in different ways. It can hold around a hundred framed images, some on view, while others await their turn in the reserve collection kept inside the structure. All the museums have smaller structures within them, they can be displayed inside the museum or on the wall. The museums can form chambers for conversation and contemplation, with their own tables and stools, as in the Museum of Chance. They can also be joined to one another in different ways to form a labyrinth. The internal relationships among them have evolved through the endless process of editing, sequencing and archiving that sustains the formal thinking essential to the realization of Singh’s work. So, within the extended family of MUSEUM BHAVAN, it is now becoming clear that File Museum and Museum of Little Ladies are sibling museums, while Museum of Photography and Museum of Furniture are cousins. -

Interview Raghu

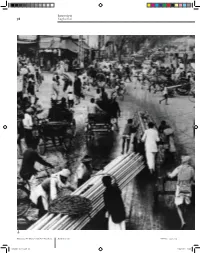

Interview 38 Raghu Rai 1 BRITISH JOURNAL OF PHOTOGRAPHY m ARcH 2011 www.bjp-online.com 038-045_03.11.indd 38 11/02/2011 16:00 39 A mAn Among mAny “India is not something you can just walk into and understand as an outsider,” says Raghu Rai, the country’s most celebrated photographer. He tells Colin Pantall why for him it’s about joining the flow, using minimal equipment and making himself as inconspicuous as possible to become part of the crowd. 1 Chawri Bazaar, Old Delhi, 1972. All images © Raghu Rai/ Magnum Photos. www.bjp-online.com m ARcH 2011 BRITISH JOURNAL OF PHOTOGRAPHY 038-045_03.11.indd 39 11/02/2011 16:01 Interview 40 Raghu Rai Raghu Rai came to photography by chance. “I was 2 Bodybuilders and staying with my elder brother Paul, who was a wrestlers on the ghats, photographer,” he recalls. “We went to a village Kolkata, 1990. to take some pictures and, when the film got 3 Dust storm, developed, my brother sent one of my images to Rajasthan, 1975. The Times in London. It was a picture of a baby donkey in the fading sunset. The picture editor there was Norman Hall, who was also the editor of the British Journal of Photography Annual, and he published it as a half page in The Times. “At the time, I was working in civil engineering, because that was what my parents wanted me to do – it was a government job, and everyone wanted a government job in India in the 1960s. But I hated it. -

Dayanita Singh Biography

ALMA ZEVI DAYANITA SINGH Born in 1961 in New Delhi, India. She lives and works in New Delhi, India. Education 1988 Photojournalism and Documentary Photography, International Center of Photography, New York City, USA 1986 Visual Communication, National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, India Selected Solo Exhibitions 2019 Dayanita Singh and Box 507 Pop Up, Frith Street Gallery, London, UK 2018 Pop-Up Book Shop, Callicoon Fine Arts, New York City, USA 2017 Museum Bhavan, Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan 2016 Suitcase Museum, Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum, Mumbai, India Museum of Shedding, Frith Street Gallery, London, UK Museum of Machines: Photographs, Projections, Volumes, MAST, Bologna, Italy Museum of Chance – Book Object, Hawa Mahal, Jaipur, India 2015 Conversation Chambers Museum Bhavan, Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, Delhi, India Book Works, Goethe-Institut. New Delhi, India Museum of Chance – A book story, MMB, Delhi, India 2014 Museum of Chance – A book story, MMB, Mumbai, India Go Away Closer, MMK, Frankfurt, Germany City Dwellers: Contemporary Art From India, Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, USA Art Institute Chicago, Chicago, USA 2013 Go Away Closer, Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre, London, UK 2012 File Museum, Frith Street Gallery, London, UK Dayanita Singh / The Adventures of a Photographer, Bildmuseet, Umeå University, Umea, Sweden Monuments of Knowledge, Photographs by Dayanita Singh, Kings College London, London, UK House of Love, Nature Morte, New Delhi, India 2011 Adventures of a Photographer, Shiseido Gallery, Tokyo, Japan -

WEEKLY Saturday October 14, 2006 ! Issue No

Established in 1936 The Doon School WEEKLY Saturday October 14, 2006 ! Issue No. 2131 Regulars 2 ScottishSection More 4 22 LTTE23 Diary377 3 Midterms4 Techno Tripping Sumit Dargan reports on a trip to Mayo College Boys’ School and the IT facilities there The trip to Mayo College Boys’ School at Ajmer We spent a good deal of time looking at the infrastruc- was an event I had looked forward to since the time the ture and mainly the software solutions in use with the school Headmaster had returned from his goodwill mission to for academic, administration and financial areas. With the the place. We left Dehradun early morning with a slight sharp and precise answers from Mr. Sriram and support drizzle, and after running past humid Delhi to dust- from Kalingasoft personnel on their ERP package, we were storm-ridden Jaipur, we reached Ajmer in the midst of all set to attend the JTM Gibson Memorial Debates. As a slight drizzle. It was a long journey by road, passing we reached the pavilion, confirmation that S & Sc forms through a multitude of tollways with varying charges of Mayo Girls’ College were there too, brought an extra ranging from Rs. 55 for a 40 km stretch to Rs. 5 for a 30 bounce to the strides of Mukho and Naman! km stretch with equally varying quality quotients. The MCGS vs. MCBS debate was perhaps the most Having been responsible for IT facilities in school contested for all the right reasons, and inputs from guests for the past seven months and the eager demands of later added value to what the youngsters had put out for the insatiable Doscos; I was more than keen to find out and against the topic, ‘The threat of Islamic ter rorism has curbed how a school older than ours in this league dealt with the freedom of expression’. -

Three Dreams Or Three Nations?

The Newsletter | No.55 | Autumn/Winter 2010 10 The Study Three dreams or three nations? A recent exhibition1 on South Asian photography entitled ‘Where Three Dreams Cross: 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh’ highlights indigenous or native photographers as a marker of what India was before the two partitions. This is to suggest that there is a history of image-making that stands outside the ambit of European practitioners. The exhibition featured over 400 photographs, a survey of images encompassing early trends and photographers from the 19th century, the social realism of the mid-20th century, the movements of photography from the studio to the streets and, eventually, the playful and dynamic recourse with image-making in the present. Rahaab Allana CULTURAL PRACTITIONERS – whether writers, musicians, Exhibitions are part of a collective enterprise, a space where Images from left Mona Ahmed, the personal life of the eunuch who lives beside painters and even photographers – have endlessly tried to artists and their work often speak for themselves. Given that to right: a graveyard, Pushpmala N.’s engagements with the historical understand the varied ways in which we should and do look India has had a varied encounter with photography over the 1. Photographer archive and the use of iconcity, the use of memory by Vivan beyond borders; and whether those lines of separation monitor last 150 years, any engagement with it in the current scenario from Mumbai, Sundaram through a relay of works on his aunt and grandfather, the inner workings and deeper cultures of engagement in our entails work that assumes to undo, abet and evolve from Unknown Artist, Umrao Sher Gil; these are only some of the links created that dealings with art, and even the curatorial practice engaged with what was done in the past.