Please Scroll Down for Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Initial Coin Offerings

BRAINY IAS Year End Review- 2017: Ministry of I&B The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, which is entrusted with the responsibility to Inform, Educate and Entertain the masses, took various initiatives in the last one year to attain its objectives. The Information sector witnessed a plethora of initiatives in the form of International cooperation with Ethiopia, devising 360 degree multimedia campaigns, release of RNI annual report on Press in India, etc. Similarly, the Films sector witnessed successful completion of the 48th IFFI and the Broadcasting sector witnessed the launch of 24x7 DD Channel for Jharkhand. The Initiatives of Ministry in different sectors are mentioned below: Information Sector Agreement on “Cooperation in the field of Information, Communication and Media” was signed between India and Ethiopia. The Agreement will encourage cooperation between mass media tools such as radio, print media, TV, social media etc. to provide more opportunities to the people of both the nations and create public accountability. 6th National Photography Awards organized. Shri Raghu Rai conferred Lifetime Achievement Award. Professional Photographer of the year award to Shri K.K. Mustafah and Amateur Photographer of the year award to Shri Ravinder Kumar. Three Heritage Books on the occasion of Centenary Celebrations of Champaran Satyagraha released. Set of books titled ‘Swachh Jungle ki kahani – Dadi ki Zubani’ Books published in 15 Indian languages by Publications Division to enable development of cleanliness habit amongst children released. “Saath Hai Vishwaas Hai, Ho Raha Vikas Hai” Exhibition organized and was put up across state capitals for duration of 5-7 days showcasing the achievements of the Government in the last 3 years in various sectors. -

The Phillips Collection Exhibition History, 1999–2021

Exhibition History, 1999–2021 Exhibition History, 1999–2021 THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION EXHIBITION HISTORY, 1999–2021 The Phillips Collection presented the following exhibitions for which it served as either an organizer or a presenting venue. * Indicates a corresponding catalogue 23, 2000. Organizing institution: The TPC.2000.6* 12, 2002. Organizing institution: 1999 Phillips Collection. William Scharf: Paintings, 1984–2000. Smith College Museum of Art, November 18, 2000–July 2, 2001. Northampton, MA. TPC.1999.1 Organizing institution: The Phillips Photographs from the Collection of 2000 Collection. Traveled to The Frederick TPC.2002.2 Dr. and Mrs. Joseph D. Lichtenberg. R. Weisman Museum of Art, Malibu, John Walker. February 16–August 4, January 12–April 25, 1999. Organizing TPC.2000.1* CA, October 20–December 15, 2001. 2002. Organizing institution: The institution: The Phillips Collection. Honoré Daumier. February 19–May Phillips Collection. 14, 2000. Organizing institutions: TPC.1999.2 The Phillips Collection, The National 2001 TPC.2002.3 An Adventurous Spirit: Calder at The Gallery of Canada, and Réunion des Howard Hodgkin. May 18–July 18, 2002. Phillips Collection. January 23–June Musées Nationaux, Paris. Traveled to 2 TPC.2001.1* Organizing institution: The Phillips 8, 1999. Organizing institutions: The additional venues. Wayne Thiebaud: A Paintings Collection. Phillips Collection and The Calder Retrospective. February 10–April 29, TPC.2000.2* Foundation. 2001. Organizing institution: Fine TPC.2002.4* An Irish Vision: Works by Tony O’Malley. Arts Museums of San Francisco, CA. Edward Weston: Photography and TPC.1999.3 April 8–July 9, 2000. Organizing Traveled to 3 additional venues. Modernism. June 1–August 18, 2002. -

Current Affairs 2013- January International

Current Affairs 2013- January International The Fourth Meeting of ASEAN and India Tourism Minister was held in Vientiane, Lao PDR on 21 January, in conjunction with the ASEAN Tourism Forum 2013. The Meeting was jointly co-chaired by Union Tourism Minister K.Chiranjeevi and Prof. Dr. Bosengkham Vongdara, Minister of Information, Culture and Tourism, Lao PDR. Both the Ministers signed the Protocol to amend the Memorandum of Understanding between ASEAN and India on Strengthening Tourism Cooperation, which would further strengthen the tourism collaboration between ASEAN and Indian national tourism organisations. The main objective of this Protocol is to amend the MoU to protect and safeguard the rights and interests of the parties with respect to national security, national and public interest or public order, protection of intellectual property rights, confidentiality and secrecy of documents, information and data. Both the Ministers welcomed the adoption of the Vision Statement of the ASEAN-India Commemorative Summit held on 20 December 2012 in New Delhi, India, particularly on enhancing the ASEAN Connectivity through supporting the implementation of the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity. The Ministers also supported the close collaboration of ASEAN and India to enhance air, sea and land connectivity within ASEAN and between ASEAN and India through ASEAN-India connectivity project. In further promoting tourism exchange between ASEAN and India, the Ministers agreed to launch the ASEAN-India tourism website (www.indiaasean.org) as a platform to jointly promote tourism destinations, sharing basic information about ASEAN Member States and India and a visitor guide. The Russian Navy on 20 January, has begun its biggest war games in the high seas in decades that will include manoeuvres off the shores of Syria. -

Open the Magazine

September 26, 2017September 26, 2017 Search Open Keyword (/) ' Columns Features Essays #Salon Openings Blogs Gallery (https://www.facebook.com/openthemagazine) (/table-of-contents/2017-09-23) $ (https://twitter.com/Openthemag) SUBSCRIBEART (/subscribe) (/digitalmagazine) 02 June 2017 (/page/rss-feeds) (/subscribe)Bonsai Gone Wild 03 JUNE 2017 IN THIS ISSUE (/article/cinema/dobaara- see-your-evil-movie- review) (/article/cinema/a- death-in-the-gunj- movie-review) ∠ ∠ () () (/article/cover- #8 story/what-powers- the-dalit- resurgence) SHARE (/#facebook) $ (/#twitter) &0 HIGHLIGHTS % (/#google_plus) (/#linkedin) (https://www.addtoany.com/share#url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.openthemagazine.com%2Farticle%2Fart- culture%2Fbonsai-gone-wild&title=Bonsai%20Gone%20Wild%20%7C%20OPEN%20Magazine)(/article/art- culture/radhika- apte-i-m-famous- for-the-right- Rosalyn D’Mello (/User/738) reasons) Rosalyn D’Mello is an art critic and the author of A Handbook For My Lover TAGGED UNDER - ( Indian art (/category/tags/indian-art-1) (/article/india/a- ( creativity (/category/tags/creativity-0) crisis-called-rahul) ( exhibition (/category/tags/exhibition-3) ( Noida (/category/tags/noida-0) ( photography (/category/tags/photography-3) ( videos (/category/tags/videos) ( expression (/category/tags/expression-3) (/article/india/the- triple-talaq- Curatorial noise overwhelms this ambitious blowback) exhibition spanning more than eight decades of creative renderings BY THE AUTHOR TO CULTIVATE BONSAI, one must have a studied understanding of botanical anatomy as well as a proclivity towards relative cruelty. What could have been a sprawling tree with unwieldy roots and shade- giving leaves must literally be trimmed to size. Verticality, every tree’s natural predisposition, must be compromised through an intricate process of clamping and trimming with a range of delicate machinery, so it can be reduced to its miniature version. -

Catalogue Fair Timings

CATALOGUE Fair Timings 28 January 2016 Thursday Select Preview: 12 - 3pm By invitation Preview: 3 - 5pm By invitation Vernissage: 5 - 9pm IAF VIP Card holders (Last entry at 8.30pm) 29 - 30 January 2016 Friday and Saturday Business Hours: 11am - 2pm Public Hours: 2 - 8pm (Last entry at 7.30pm) 31 January 2016 Sunday Public Hours: 11am - 7pm (Last entry at 6.30pm) India Art Fair Team Director's Welcome Neha Kirpal Zain Masud Welcome to our 2016 edition of India Art Fair. Founding Director International Director Launched in 2008 and anticipating its most rigorous edition to date Amrita Kaur Srijon Bhattacharya with an exciting programme reflecting the diversity of the arts in Associate Fair Director Director - Marketing India and the region, India Art Fair has become South Asia's premier and Brand Development platform for showcasing modern and contemporary art. For our 2016 Noelle Kadar edition, we are delighted to present BMW as our presenting partner VIP Relations Director and JSW as our associate partner, along with continued patronage from our preview partner, Panerai. Saheba Sodhi Vishal Saluja Building on its success over the past seven years, India Art Senior Manager - Marketing General Manager - Finance Fair presents a refreshed, curatorial approach to its exhibitor and Alliances and Operations programming with new and returning international participants Isha Kataria Mankiran Kaur Dhillon alongside the best programmes from the subcontinent. Galleries, Vip Relations Manager Programming and Client Relations will feature leading Indian and international exhibitors presenting both modern and contemporary group shows emphasising diverse and quality content. Focus will present select galleries and Tanya Singhal Wol Balston organisations showing the works of solo artists or themed exhibitions. -

General Studies Series

IAS General Studies Series Current Affairs (Prelims), 2013 by Abhimanu’s IAS Study Group Chandigarh © 2013 Abhimanu Visions (E) Pvt Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system or otherwise, without prior written permission of the owner/ publishers or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act, 1957. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claim for the damages. 2013 EDITION Disclaimer: Information contained in this work has been obtained by Abhimanu Visions from sources believed to be reliable. However neither Abhimanu's nor their author guarantees the accuracy and completeness of any information published herein. Though every effort has been made to avoid any error or omissions in this booklet, in spite of this error may creep in. Any mistake, error or discrepancy noted may be brought in the notice of the publisher, which shall be taken care in the next edition but neither Abhimanu's nor its authors are responsible for it. The owner/publisher reserves the rights to withdraw or amend this publication at any point of time without any notice. TABLE OF CONTENTS PERSONS IN NEWS .............................................................................................................................. 13 NATIONAL AFFAIRS .......................................................................................................................... -

Climate Changing: on Artists, Institutions, and the Social Environment

i CLIMATE CHANGING CLIMATE WHY CAN’T YOU TELL ME SCORE WHAT YOU NEED Somewhere our body needs party favors attending sick and resting temperatures times hot unevens twice I ask myself all the time too ward draw pop left under right Just try and squeeze me. Pause. What would you do? Fall down off my feet and try waking tired ex muses Like, you either know I can and work on it with me Or know I can’t and wouldn’t want your baby to go through what I have to go through Over prepared for three nights. Over it all scared for three nights. Tell me the unwell of never been better. Are we still good? Are we still good? TABLE OF CONTENTS Director’s Foreword 4 Johanna Burton A Climate for Changing 6 Lucy I. Zimmerman On Chris Burden’s Wexner Castle 10 Lucy I. Zimmerman Notes on Chris Burden’s Through the Night Softly 15 Pope.L WE LEFT THEM NOTHING 17 Demian DinéYazhi´ Untitled 21 Jibade-Khalil Huffman Scores 1, 3, 13, 23, 27, 50 Park McArthur and Constantina Zavitsanos Questioning Access 25 Advisory Committee Roundtable Discussion Artists in the Exhibition 29 Acknowledgments 47 3 BLANKET (STATEMENT) SCORE Why can’t you just tell me what you need DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD 4 Johanna Burton, Executive Director Opening in the first month of 2021 (or at least set to committee’s roundtable discussion further explores, open then at the time of this writing), Climate Changing: the exhibition intends not to inventory nor propose On Artists, Institutions, and the Social Environment solutions for these considerable challenges, but rather comes at a time of great uncertainty for cultural or- to provide artists a forum for bringing the issues into ganizations. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

Allan Desouza Opens Jan

Stacey Ravel Abarbanel, [email protected] For Immediate Use 310/825-4288 November 24, 2010 His Masters' Tools: Recent Work by Allan deSouza Opens Jan. 23 at the Fowler Museum at UCLA His Masters' Tools: Recent Work by Allan deSouza—on view at the Fowler Museum from Jan. 23–May 29, 2011 explores the oeuvre of the San Francisco-based performance and photo- conceptual artist, Allan deSouza. The exhibition includes nearly thirty works that engage with the effects of Euro-American empire and the racial underpinnings of colonial power. The works on display run the gamut from large-scale, gorgeously colored and sensuous abstractions to modestly-sized photographic prints. His Masters' Tools focuses on two new series created especially for this Fowler exhibition—Rdctns and The Third Eye—which explore issues of race in relation to western art history by reworking primitivist paintings by Paul Gauguin and Henri Rousseau and self-portraits by canonical artists such as Chuck Close, Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol (left). Both series use digital manipulation to play with notions of artistic and technological mastery and to blur the boundaries between photography and painting. The exhibition also draws on work from earlier series, The Searchers (2003), The Lost Pictures (2004/5), and X.Man (2009), to provide a conceptual and formal context for deSouza’s newest experiments. The Searchers, a series of landscape photographs that displace deSouza’s own anxieties and preoccupations onto those of a group of tourists on safari outside Nairobi, is the outcome of his efforts to reconnect with the country of his birth on a return trip to Kenya in 2002. -

20Years of Sahmat.Pdf

SAHMAT – 20 Years 1 SAHMAT 20 YEARS 1989-2009 A Document of Activities and Statements 2 PUBLICATIONS SAHMAT – 20 YEARS, 1989-2009 A Document of Activities and Statements © SAHMAT, 2009 ISBN: 978-81-86219-90-4 Rs. 250 Cover design: Ram Rahman Printed by: Creative Advertisers & Printers New Delhi Ph: 98110 04852 Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust 29 Ferozeshah Road New Delhi 110 001 Tel: (011) 2307 0787, 2338 1276 E-mail: [email protected] www.sahmat.org SAHMAT – 20 Years 3 4 PUBLICATIONS SAHMAT – 20 Years 5 Safdar Hashmi 1954–1989 Twenty years ago, on 1 January 1989, Safdar Hashmi was fatally attacked in broad daylight while performing a street play in Sahibabad, a working-class area just outside Delhi. Political activist, actor, playwright and poet, Safdar had been deeply committed, like so many young men and women of his generation, to the anti-imperialist, secular and egalitarian values that were woven into the rich fabric of the nation’s liberation struggle. Safdar moved closer to the Left, eventually joining the CPI(M), to pursue his goal of being part of a social order worthy of a free people. Tragically, it would be of the manner of his death at the hands of a politically patronised mafia that would single him out. The spontaneous, nationwide wave of revulsion, grief and resistance aroused by his brutal murder transformed him into a powerful symbol of the very values that had been sought to be crushed by his death. Such a death belongs to the revolutionary martyr. 6 PUBLICATIONS Safdar was thirty-four years old when he died. -

Interview Raghu

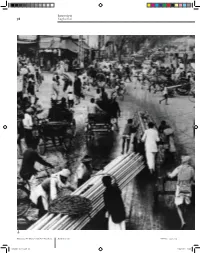

Interview 38 Raghu Rai 1 BRITISH JOURNAL OF PHOTOGRAPHY m ARcH 2011 www.bjp-online.com 038-045_03.11.indd 38 11/02/2011 16:00 39 A mAn Among mAny “India is not something you can just walk into and understand as an outsider,” says Raghu Rai, the country’s most celebrated photographer. He tells Colin Pantall why for him it’s about joining the flow, using minimal equipment and making himself as inconspicuous as possible to become part of the crowd. 1 Chawri Bazaar, Old Delhi, 1972. All images © Raghu Rai/ Magnum Photos. www.bjp-online.com m ARcH 2011 BRITISH JOURNAL OF PHOTOGRAPHY 038-045_03.11.indd 39 11/02/2011 16:01 Interview 40 Raghu Rai Raghu Rai came to photography by chance. “I was 2 Bodybuilders and staying with my elder brother Paul, who was a wrestlers on the ghats, photographer,” he recalls. “We went to a village Kolkata, 1990. to take some pictures and, when the film got 3 Dust storm, developed, my brother sent one of my images to Rajasthan, 1975. The Times in London. It was a picture of a baby donkey in the fading sunset. The picture editor there was Norman Hall, who was also the editor of the British Journal of Photography Annual, and he published it as a half page in The Times. “At the time, I was working in civil engineering, because that was what my parents wanted me to do – it was a government job, and everyone wanted a government job in India in the 1960s. But I hated it.