Background Briefing: the New 'Kingmaker' Seats That Could Decide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migrant Voters in the 2015 General Election

Migrant Voters in the 2015 General Election Dr Robert Ford, Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE), The University of Manchester Ruth Grove-White, Migrants’ Rights Network Migrant Voters in the 2015 General Election Content 1. Introduction 2 2. This briefing 4 3. Migrant voters and UK general elections 5 4. Migrant voters in May 2015 6 5. Where are migrant voters concentrated? 9 6. Where could migrant votes be most influential? 13 7. Migrant voting patterns and intentions 13 8. Conclusion 17 9. Appendix 1: Methodology 18 10. References 19 1. Migrant Voters in the 2015 General Election 1. Introduction The 2015 general election looks to be the closest and least predictable in living memory, and immigration is a key issue at the heart of the contest. With concerns about the economy slowly receding as the financial crisis fades into memory, immigration has returned to the top of the political agenda, named by more voters as their most pressing political concern than any other issue1. Widespread anxiety about immigration has also been a key driver behind the surge in support for UKIP, though it is far from the only issue this new party is mobilizing around2. Much attention has been paid to the voters most anxious about immigration, and what can be done to assuage their concerns. Yet amidst this fierce debate about whether, and how, to restrict immigration, an important electoral voice has been largely overlooked: that of migrants themselves. In this briefing, we argue that the migrant The political benefits of engaging with electorate is a crucial constituency in the 2015 migrant voters could be felt far into the election, and will only grow in importance in future. -

Understanding Governments Attitudes to Social Housing

Understanding Government’s Attitudes to Social Housing through the Application of Politeness Theory Abstract This paper gives a brief background of housing policy in England from the 2010 general election where David Cameron was appointed Prime Minister of a Coalition government with the Liberal Democrats and throughout the years that followed. The study looks at government attitudes towards social housing from 2015, where David Cameron had just become Prime Minister of an entirely Conservative Government, to 2018 following important events such as Brexit and the tragic Grenfell Tower fire. Through the application of politeness theory, as originally put forward by Brown & Levinson (1978, 1987), the study analysis the speeches of key ministers to the National Housing Summit and suggests that the use of positive and negative politeness strategies could give an idea as to the true attitudes of government. Word Count: 5472 Emily Pumford [email protected] Job Title: Researcher 1 Organisation: The Riverside Group Current research experience: 3 years Understanding Government’s Attitudes to Social Housing through the Application of Politeness Theory Introduction and Background For years, the Conservative Party have prided themselves on their support for home ownership. From Margaret Thatcher proudly proclaiming that they had taken the ‘biggest single step towards a home-owning democracy ever’ (Conservative Manifest 1983), David Cameron arguing that they would become ‘once again, the party of home ownership in our country’ (Conservative Party Conference Speech 2014) and Theresa May, as recently as 2017, declaring that they would ‘make the British Dream a reality by reigniting home ownership in Britain’ (Conservative Party Conference Speech 2017). -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 11 January 2018 On 8-9 January 2018, Prime Minister Theresa May conducted a ministerial reshuffle. This guide has been updated to reflect the changes. The Conservative government does not have a parliamentary majority of MPs but has a confidence and supply deal with the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). The DUP will support the government in key votes, such as on the Queen's Speech and Budgets, as well as Brexit and security matters, which are likely to dominate most of the current Parliament. This gives the government a working majority of 13. This is a briefing for BIA members on the new Government and key ministerial appointments for our sector. Contents Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministerial brief for the Life Sciences.............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Theresa May’s team in Number 10 ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities pertinent -

Uk Government and Special Advisers

UK GOVERNMENT AND SPECIAL ADVISERS April 2019 Housing Special Advisers Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under INTERNATIONAL 10 DOWNING Toby Lloyd Samuel Coates Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Deputy Chief Whip STREET DEVELOPMENT Foreign Affairs/Global Salma Shah Rt Hon Tobias Ellwood MP Kwasi Kwarteng MP Jackie Doyle-Price MP Jake Berry MP Christopher Pincher MP Prime Minister Britain James Hedgeland Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Secretary of State Chief Whip (Lords) Rt Hon Theresa May MP Ed de Minckwitz Olivia Robey Secretary of State INTERNATIONAL Parliamentary Under Secretary of State and Minister for Women Stuart Andrew MP TRADE Secretary of State Heather Wheeler MP and Equalities Rt Hon Lord Taylor Chief of Staff Government Relations Minister of State Baroness Blackwood Rt Hon Penny of Holbeach CBE for Immigration Secretary of State and Parliamentary Under Mordaunt MP Gavin Barwell Special Adviser JUSTICE Deputy Chief Whip (Lords) (Attends Cabinet) President of the Board Secretary of State Deputy Chief of Staff Olivia Oates WORK AND Earl of Courtown Rt Hon Caroline Nokes MP of Trade Rishi Sunak MP Special Advisers Legislative Affairs Secretary of State PENSIONS JoJo Penn Rt Hon Dr Liam Fox MP Parliamentary Under Laura Round Joe Moor and Lord Chancellor SCOTLAND OFFICE Communications Special Adviser Rt Hon David Gauke MP Secretary of State Secretary of State Lynn Davidson Business Liason Special Advisers Rt Hon Amber Rudd MP Lord Bourne of -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Tory Modernisation 2.0 Tory Modernisation

Edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg Guy and Shorthouse Ryan by Edited TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 MODERNISATION TORY edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 THE FUTURE OF THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 The future of the Conservative Party Edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg The moral right of the authors has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a re- trieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. Bright Blue is an independent, not-for-profit organisation which cam- paigns for the Conservative Party to implement liberal and progressive policies that draw on Conservative traditions of community, entre- preneurialism, responsibility, liberty and fairness. First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Bright Blue Campaign www.brightblue.org.uk ISBN: 978-1-911128-00-7 Copyright © Bright Blue Campaign, 2013 Printed and bound by DG3 Designed by Soapbox, www.soapbox.co.uk Contents Acknowledgements 1 Foreword 2 Rt Hon Francis Maude MP Introduction 5 Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg 1 Last chance saloon 12 The history and future of Tory modernisation Matthew d’Ancona 2 Beyond bare-earth Conservatism 25 The future of the British economy Rt Hon David Willetts MP 3 What’s wrong with the Tory party? 36 And why hasn’t -

AIRE VALLEY MAG Community News and Local Business Directory

AIRE VALLEY MAG Community News And Local Business Directory September 2009 DISTRIBUTED FREE TO SELECTED AREAS IN CROSS HILLS, GLUSBURN, SUTTON, EASTBURN, STEETON, SILSDEN, AND KEIGHLEY Welcome to your new community WORTH & AIRE VALLEY MAGS magazine, the Aire Valley Mag! It is our Community News And Local Business Directories aim to bring community minded stories WORTHWORTH VALLEY MAG MAG WORTH VALLEY MAG Community News And Local Business Directory Community News And Local B Community Ne usiness Directory and reflections of local life together with May 2008 ws And Local Business Directory July/August 2008 WORTHCommunity News AndVALLEY Local Business Directory MAG a handy business directory. Keep your June 2009 April 2009 AIRECommunity NewsVALLEY And Local Business MAG Directory mag close to hand and use it thoughout the month to find local services, products, and events. Our free community pages will STANBURY,DISTRIBUTED OXEN DISTRIBUTED keep you up to speed with group activities STANBURY, OXENHOPE, FREE HAWORTH, TO OAKWORTH, LEE OLDFIELD, FREE with over 15,000 readers!S & CROSS ROADS HOPE, HAWORTH, TO OAKWORTH, LEES & OLDFIEL CR w w w . w o r t h v a l l e y m a g . c o . uwww.worthvalleymag.co.uk k with over 16,000 readers! TO OAKWORTH, OLDFIELD, FREE DISTRIBUTED OSS ROADSD, and various community organisations. STANBURY, OXENHOPE,with over HAWORTH, 15,000 readers! LEES & CROSS ROADS www.worthvalleymag.co.uk TO Silsden, Steeton, Eastburn, We support local trade and and FREE www.airevalleymag.co.uk DISTRIBUTED Cross Hills & Sutton encourage others to do the same. Our Contact us: 01535 642227 Elizabeth Barker, Editor motto is Local, Affordable, Community 8FEEJOHTBU"TINPVOU Spirited. -

Register of All-Party Parliamentary Groups

Register of All-Party Parliamentary Groups Published 29 August 2018 REGISTER OF ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUPS Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 The Nature of All-Party Parliamentary Groups ...................................................................................................... 3 Information and advice about All-Party Parliamentary Groups ............................................................................ 3 COUNTRY GROUPS .................................................................................................................................................... 4 SUBJECT GROUPS ................................................................................................................................................... 187 2 | P a g e REGISTER OF ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUPS INTRODUCTION The Nature of All-Party Parliamentary Groups An All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) consists of Members of both Houses who join together to pursue a particular topic or interest. In order to use the title All-Party Parliamentary Group, a Group must be open to all Members of both Houses, regardless of party affiliation, and must satisfy the rules agreed by the House for All-Party Parliamentary Groups. The Register of All-Party Parliamentary Groups, which is maintained by the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards, is a definitive list of such groups. It contains the financial -

Resources/Contacts for Older People's Action Groups on Housing And

Resources/contacts for Older People’s Action Groups on housing and ageing for the next General Election It is not long before the next general election. Politicians, policy makers and others are developing their manifestos for the next election and beyond. The Older People’s Housing Champion’s network (http://housingactionblog.wordpress.com/) has been developing its own manifesto on housing and will be looking at how to influence the agenda locally and nationally in the months ahead. Its manifesto is at http://housingactionblog.wordpress.com/2014/08/07/our-manifesto-for-housing-safe-warm-decent-homes-for-older-people/ To help Older People’s Action Groups, Care & Repair England has produced this contact list of key people to influence in the run up to the next election. We have also included some ideas of the sort of questions you might like to ask politicians and policy makers when it comes to housing. While each party is still writing their manifesto in anticipation of the Party Conference season in the autumn, there are opportunities to contribute on-line at the party websites included. National Contacts – Politicians, Parties and Policy websites Name Constituency Email/Website Twitter www.conservatives.com/ Conservative Party @conservatives www.conservativepolicyforum.com/1 [email protected] Leader Rt Hon David Cameron MP Witney, Oxfordshire @David_Cameron www.davidcameron.com/ Secretary of State for Brentwood and Ongar, [email protected] Communities and Local Rt Hon Eric Pickles MP @EricPickles Essex www.ericpickles.com -

Consultation Statement – Table of Responses Consultee Plan Support/ Comment PC Response Plan Ref

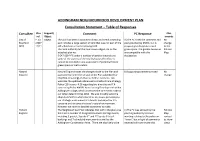

ADDINGHAM NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN Consultation Statement – Table of Responses Consultee Plan Support/ Comment PC Response Plan ref. Object amends City of P. 53 Object The plan has been inaccurately drawn and needs amending A) The PC notes the comment and No Bradford ANDP as it includes a large section of land that was not part of the plan provided by BMDC, but is change MDC 11/11 old school site or former playing field. proposing to designate a local to the The local authority let the land shown edged red on the green space. The garden tenancies Policies attached plan no. are compatible with this Map. S-047-009-PFG under a number of garden tenancies to designation. some of the owners of the nearby houses therefore it cannot be included in any assessment of potential future green space in that location. Natural Natural England notes the changes made to the Plan and B) Supporting comments noted No England assessments [since the version of the Plan submitted for change SEA/HRA screening] and has no further concerns. We welcome the updated references to Bradford Core Strategy Policy CS8 in para. 4.20 regarding bio-diversity and 7.4 concerning Policy ANDP1 New Housing Development within Addingham village, which addresses the comments made in our letter dated 15 May 2018. We also broadly welcome chap.4 of the Plan which identifies key issues pertaining to our strategic environmental interests and objective 3 to conserve and enhance the area’s natural environment. However we have no detailed comments to make. Historic The Neighbourhood Plan indicates that within the plan area C) The PC was advised by the Policies England there are a number of designated cultural heritage assets, planning authority to revise Map including 3 grade I, 3 grade II* and 115 grade II listed wording relating to the policy on revised buildings and 7 scheduled monuments as well as the “views”, but in light of comments to show Addingham Conservation Area. -

Matthew Gregory Chief Executive Firstgroup Plc 395

Matthew Gregory House of Commons, Chief Executive London, FirstGroup plc SW1A0AA 395 King Street Aberdeen AB24 5RP 15 October 2019 Dear Mr Gregory As West Yorkshire MPs, we are writing as FirstGroup are intending to sell First Bus and to request that the West Yorkshire division of the company is sold as a separate entity. This sale represents a singular opportunity to transform bus operations in our area and we believe it is in the best interests of both FirstGroup and our constituents for First Bus West Yorkshire to be taken into ownership by the West Yorkshire Combined Authority (WYCA). To this end, we believe that WYCA should have the first option to purchase this division. In West Yorkshire, the bus as a mode of travel is particularly relied upon by many of our constituents to get to work, appointments and to partake in leisure activities. We have a long-shared aim of increasing the usage of buses locally as a more efficient and environmentally friendly alternative to the private car. We believe that interest is best served by allowing for passengers to have a stake in their own service through the local combined authority. There is wide spread public support for this model as a viable direction for the service and your facilitation of this process through the segmentation of the sale can only reflect well on FirstGroup. We, as representatives of the people of West Yorkshire request a meeting about the future of First Bus West Yorkshire and consideration of its sale to West Yorkshire Combined Authority. Yours sincerely, Alex Sobel MP Tracey Brabin MP Imran Hussain MP Judith Cummins MP Naz Shah MP Thelma Walker MP Paula Sherriff MP Holly Lynch MP Jon Trickett MP Barry Sheerman MP John Grogan MP Hilary Benn MP Richard Burgon MP Fabian Hamilton MP Rachel Reeves MP Yvette Cooper MP Mary Creagh MP Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org). -

The Land Border Between Northern Ireland and Ireland

House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee The land border between Northern Ireland and Ireland Second Report of Session 2017–19 HC 329 House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee The land border between Northern Ireland and Ireland Second Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 March 2018 HC 329 Published on 16 March 2018 by authority of the House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee The Northern Ireland Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Northern Ireland Office (but excluding individual cases and advice given by the Crown Solicitor); and other matters within the responsibilities of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland (but excluding the expenditure, administration and policy of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions, Northern Ireland and the drafting of legislation by the Office of the Legislative Counsel). Current membership Dr Andrew Murrison MP (Conservative, South West Wiltshire) (Chair) Mr Gregory Campbell MP (Democratic Unionist Party, East Londonderry) Mr Robert Goodwill MP (Conservative, Scarborough and Whitby ) John Grogan MP (Labour, Keighley) Mr Stephen Hepburn MP (Labour, Jarrow) Lady Hermon MP (Independent, North Down) Kate Hoey MP (Labour, Vauxhall) Jack Lopresti MP (Conservative, Filton and Bradley Stoke) Conor McGinn MP (Labour, St Helens North) Nigel Mills MP (Conservative, Amber Valley) Ian Paisley MP (Democratic Unionist Party, North Antrim) Jim Shannon MP (Democratic Unionist Party, Strangford) Bob Stewart MP (Conservative, Beckenham) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152.