The Land Border Between Northern Ireland and Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing the Development- Displacement Nexus in Turkey

Assessing the Development- Displacement Nexus in Turkey Working Paper Fulya Memişoğlu November 2018 Assessing the Development- Displacement Nexus in Turkey Working Paper Acknowledgements This report is an output of the project Study on Refugee Protection and Development: Assessing the Development-Displacement Nexus in Regional Protection Policies, funded by the OPEC Fund for Inter- national Development (OFID) and the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD). The author and ICMPD gratefully acknowledge OFID’s support. While no fieldwork was conducted for this report, the author thanks the Turkey Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) of the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Development, ICMPD Tur- key and the Refugee Studies Centre of Oxford University for their valuable inputs to previous research, which contributed to the author’s work. The author also thanks Maegan Hendow for her valuable feedback on this report. International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) Gonzagagasse 1 A-1010 Vienna www.icmpd.com International Centre for Migration Policy Development Vienna, Austria All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission of the copyright owners. The content of this study does not reflect the official opinion of OFID or ICMPD. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the study lies entirely with the author. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS \ 3 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Acronyms 6 1. Introduction 7 1.1 The Syrian crisis and Turkey 7 2. Refugee populations in Turkey 9 2.1 Country overview 9 2.2 Evolution and dynamics of the Syrian influx in Turkey 11 2.3 Characteristics of the Syrian refugee population 15 2.4 Legal status issues 17 2.5 Other relevant refugee flows 19 3. -

Border Security: the Role of the U.S. Border Patrol

Border Security: The Role of the U.S. Border Patrol Chad C. Haddal Specialist in Immigration Policy August 11, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32562 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Border Security: The Role of the U.S. Border Patrol Summary The United States Border Patrol (USBP) has a long and storied history as our nation’s first line of defense against unauthorized migration. Today, the USBP’s primary mission is to detect and prevent the entry of terrorists, weapons of mass destruction, and illegal aliens into the country, and to interdict drug smugglers and other criminals along the border. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 dissolved the Immigration and Naturalization Service and placed the USBP within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Within DHS, the USBP forms a part of the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection under the Directorate of Border and Transportation Security. During the last decade, the USBP has seen its budget and manpower more than triple. This expansion was the direct result of congressional concerns about illegal immigration and the agency’s adoption of “Prevention Through Deterrence” as its chief operational strategy in 1994. The strategy called for placing USBP resources and manpower directly at the areas of greatest illegal immigration in order to detect, deter, and apprehend aliens attempting to cross the border between official points of entry. Post 9/11, the USBP refocused its strategy on preventing the entry of terrorists and weapons of mass destruction, as laid out in its recently released National Strategy. -

H. Khachatrian. Economic Impacts of Re-Opening the Armenian-Turkish

Economic Impacts of Re-Opening the Armenian-Turkish Border By Haroutiun Khachatrian 1 The economic consequences of the possible re-opening of the Armenian-Turkish border will appear quickly and will mean a rapid improvement for both countries, but especially for Armenia. The current economic relationships between Armenia and Turkey can be characterized in short as follows: Turkey exports goods to Armenia worth some 260 million dollars a year, whereas imports of Armenian goods to Turkey are worth a mere 1.9 million dollars (data of 2008). In other words, the Armenian market is open for Turkish goods, while the opposite is not true, as Turkey applies a de-facto embargo (not declared officially) to imports from Armenia. All of this cargo transfer is chanelled through third countries, mainly Georgia. This shows the first possible benefit for Armenia once the de-facto embargo is lifted. The huge Turkish market, a country of 70 million, would become available for Armenian exporters. Meanwhile, today the immediate markets available for Armenian goods are only the market of Armenia itself (3.2 million people) and Georgia (4.5 million), both being poor countries which restricts the volume of the market. Two other neighbors of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Iran are practically inaccessible for Armenian exports, the former for political reasons and the latter because of high trade barriers. Along these lines, opening the Turkish market to Armenia would greatly improve the investment rating of Armenia as the limited volumes of markets nearby make it a risky site for investments, today. 1 The author is an analyst and editor with the Yerevan based news agency Noyan Tapan. -

Open Or Closed: Balancing Border Policy with Human Rights Elizabeth M

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 96 | Issue 2 Article 3 2007 Open or Closed: Balancing Border Policy with Human Rights Elizabeth M. Bruch Valparaiso University Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Immigration Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Bruch, Elizabeth M. (2007) "Open or Closed: Balancing Border Policy with Human Rights," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 96 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol96/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Open or Closed: Balancing Border Policy with Human Rights Elizabeth M. Bruch' "We are living in a time when civil rights, meaning basic human rights, are being reformulated, redefined, and extended to new categories of people." Roger Nett (1971) "We should not be afraid of open borders." 3 Bill Ong Hing (2006) INTRODUCTION O PEN borders have not been a popular idea in the United States for at least a century.4 Since the federal government became involved in immigration regulation in the late 1800s, the history of immigration policy has generally been one of increasing restrictions and limitations.5 I Associate Professor of Law, Valparaiso University School of Law; Visiting Scholar, Centre for Feminist Legal Studies, Law Faculty, University of British Columbia. -

The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989

FORUM The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989 ✣ Commentaries by Michael Kraus, Anna M. Cienciala, Margaret K. Gnoinska, Douglas Selvage, Molly Pucci, Erik Kulavig, Constantine Pleshakov, and A. Ross Johnson Reply by Mark Kramer and V´ıt Smetana Mark Kramer and V´ıt Smetana, eds. Imposing, Maintaining, and Tearing Open the Iron Curtain: The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014. 563 pp. $133.00 hardcover, $54.99 softcover, $54.99 e-book. EDITOR’S NOTE: In late 2013 the publisher Lexington Books, a division of Rowman & Littlefield, put out the book Imposing, Maintaining, and Tearing Open the Iron Curtain: The Cold War and East-Central Europe, 1945–1989, edited by Mark Kramer and V´ıt Smetana. The book consists of twenty-four essays by leading scholars who survey the Cold War in East-Central Europe from beginning to end. East-Central Europe was where the Cold War began in the mid-1940s, and it was also where the Cold War ended in 1989–1990. Hence, even though research on the Cold War and its effects in other parts of the world—East Asia, South Asia, Latin America, Africa—has been extremely interesting and valuable, a better understanding of events in Europe is essential to understand why the Cold War began, why it lasted so long, and how it came to an end. A good deal of high-quality scholarship on the Cold War in East-Central Europe has existed for many years, and the literature on this topic has bur- geoned in the post-Cold War period. -

Passports Into Credit Cards: on the Borders and Spaces of Neoliberal Citizenship

Passports into credit cards: On the borders and spaces of neoliberal citizenship Matthew Sparke University of Washington Forthcoming in Joel Migdal ed. Boundaries and Belonging (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) Copyright protected under Matthew Sparke. Permission to cite may be directed to the Author. "We have included in our design the necessary technological platforms to ensure that the card will have a useful life of approximately five years. Most importantly for commercial users today, it will sport the ubiquitous magnetic strip which the government will not use, making it completely available to the commercial sector. We have also included a microchip in the design as we will require some of the available storage space for automated inspections. We will make the remainder of the chip’s storage available to our commercial partners. We think this is especially significant because of the recent announcement by Visa, MasterCard and Europay of their joint specification for chip- based credit cards. To further the appeal of this idea to the commercial sector, we will also allow cards prepared by our partners to display the logo of the partner. This would create in the mind of the card holder an instant link between our high technology application and the sponsoring corporation. Just think of the possibilities for a frequent traveler pulling out a card bearing the IBM or United Airlines logo, for example. Now potentiate that image by seeing the card as a charge card, an airline ticket, a medium by which you access telecommunications systems, an electronic bank, and/or any other card- based application you can conceive." Ronald Hays1 1 These plans for a new kind of passport using credit card and biometric technology are not the plans of a banker, a commercial web systems designer, or some other corporate planner. -

Bordering Two Unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics de Mars, Sylvia; Murray, Colin; O'Donoghue, Aiofe; Warwick, Ben Book — Published Version Bordering two unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit Policy Press Shorts: Policy & Practice Provided in Cooperation with: Bristol University Press Suggested Citation: de Mars, Sylvia; Murray, Colin; O'Donoghue, Aiofe; Warwick, Ben (2018) : Bordering two unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit, Policy Press Shorts: Policy & Practice, ISBN 978-1-4473-4622-7, Policy Press, Bristol, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv56fh0b This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190846 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

Register of All-Party Parliamentary Groups

Register of All-Party Parliamentary Groups Published 29 August 2018 REGISTER OF ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUPS Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 The Nature of All-Party Parliamentary Groups ...................................................................................................... 3 Information and advice about All-Party Parliamentary Groups ............................................................................ 3 COUNTRY GROUPS .................................................................................................................................................... 4 SUBJECT GROUPS ................................................................................................................................................... 187 2 | P a g e REGISTER OF ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUPS INTRODUCTION The Nature of All-Party Parliamentary Groups An All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) consists of Members of both Houses who join together to pursue a particular topic or interest. In order to use the title All-Party Parliamentary Group, a Group must be open to all Members of both Houses, regardless of party affiliation, and must satisfy the rules agreed by the House for All-Party Parliamentary Groups. The Register of All-Party Parliamentary Groups, which is maintained by the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards, is a definitive list of such groups. It contains the financial -

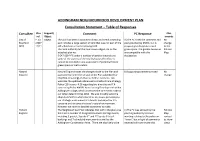

Consultation Statement – Table of Responses Consultee Plan Support/ Comment PC Response Plan Ref

ADDINGHAM NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN Consultation Statement – Table of Responses Consultee Plan Support/ Comment PC Response Plan ref. Object amends City of P. 53 Object The plan has been inaccurately drawn and needs amending A) The PC notes the comment and No Bradford ANDP as it includes a large section of land that was not part of the plan provided by BMDC, but is change MDC 11/11 old school site or former playing field. proposing to designate a local to the The local authority let the land shown edged red on the green space. The garden tenancies Policies attached plan no. are compatible with this Map. S-047-009-PFG under a number of garden tenancies to designation. some of the owners of the nearby houses therefore it cannot be included in any assessment of potential future green space in that location. Natural Natural England notes the changes made to the Plan and B) Supporting comments noted No England assessments [since the version of the Plan submitted for change SEA/HRA screening] and has no further concerns. We welcome the updated references to Bradford Core Strategy Policy CS8 in para. 4.20 regarding bio-diversity and 7.4 concerning Policy ANDP1 New Housing Development within Addingham village, which addresses the comments made in our letter dated 15 May 2018. We also broadly welcome chap.4 of the Plan which identifies key issues pertaining to our strategic environmental interests and objective 3 to conserve and enhance the area’s natural environment. However we have no detailed comments to make. Historic The Neighbourhood Plan indicates that within the plan area C) The PC was advised by the Policies England there are a number of designated cultural heritage assets, planning authority to revise Map including 3 grade I, 3 grade II* and 115 grade II listed wording relating to the policy on revised buildings and 7 scheduled monuments as well as the “views”, but in light of comments to show Addingham Conservation Area. -

Matthew Gregory Chief Executive Firstgroup Plc 395

Matthew Gregory House of Commons, Chief Executive London, FirstGroup plc SW1A0AA 395 King Street Aberdeen AB24 5RP 15 October 2019 Dear Mr Gregory As West Yorkshire MPs, we are writing as FirstGroup are intending to sell First Bus and to request that the West Yorkshire division of the company is sold as a separate entity. This sale represents a singular opportunity to transform bus operations in our area and we believe it is in the best interests of both FirstGroup and our constituents for First Bus West Yorkshire to be taken into ownership by the West Yorkshire Combined Authority (WYCA). To this end, we believe that WYCA should have the first option to purchase this division. In West Yorkshire, the bus as a mode of travel is particularly relied upon by many of our constituents to get to work, appointments and to partake in leisure activities. We have a long-shared aim of increasing the usage of buses locally as a more efficient and environmentally friendly alternative to the private car. We believe that interest is best served by allowing for passengers to have a stake in their own service through the local combined authority. There is wide spread public support for this model as a viable direction for the service and your facilitation of this process through the segmentation of the sale can only reflect well on FirstGroup. We, as representatives of the people of West Yorkshire request a meeting about the future of First Bus West Yorkshire and consideration of its sale to West Yorkshire Combined Authority. Yours sincerely, Alex Sobel MP Tracey Brabin MP Imran Hussain MP Judith Cummins MP Naz Shah MP Thelma Walker MP Paula Sherriff MP Holly Lynch MP Jon Trickett MP Barry Sheerman MP John Grogan MP Hilary Benn MP Richard Burgon MP Fabian Hamilton MP Rachel Reeves MP Yvette Cooper MP Mary Creagh MP Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org).