Ordination in the Ancient Church (I) Everett Ef Rguson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Korean-American Methodists' Response to the UMC Debate Over

religions Article Loving My New Neighbor: The Korean-American Methodists’ Response to the UMC Debate over LGBTQ Individuals in Everyday Life Jeyoul Choi Department of Religion, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA; [email protected] Abstract: The recent nationwide debate of American Protestant churches over the ordination and consecration of LGBTQ clergymen and laypeople has been largely divisive and destructive. While a few studies have paid attention to individual efforts of congregations to negotiate the heated conflicts as their contribution to the denominational debate, no studies have recounted how post-1965 immigrants, often deemed as “ethnic enclaves apart from larger American society”, respond to this religious issue. Drawing on an ethnographic study of a first-generation Korean Methodist church in the Tampa Bay area, Florida, this article attempts to fill this gap in the literature. In brief, I argue that the Tampa Korean-American Methodists’ continual exposure to the Methodist Church’s larger denominational homosexuality debate and their personal relationships with gay and lesbian friends in everyday life together work to facilitate their gradual tolerance toward sexual minorities as a sign of their accommodation of individualistic and democratic values of American society. Keywords: homosexuality and LGBTQ people; United Methodist Church; post-1965 immigrants; Korean-American evangelicals Citation: Choi, Jeyoul. 2021. Loving My New Neighbor: The Korean-American Methodists’ Response to the UMC Debate over 1. Introduction LGBTQ Individuals in Everyday Life. The discourses of homosexuality and LGBTQ individuals in American Protestantism Religions 12: 561. https://doi.org/ are polarized by the research that enunciates each denomination’s theological stance 10.3390/rel12080561 and conflicts over the case studies of individual sexual minorities’ struggle within their congregations. -

When You Consider Ordination

WHEN YOU CONSIDER ORDINATION CONSERVATIVE CONGREGATIONAL CHRISTIAN CONFERENCE April 2017 CONTENTS Ff When Considering Ordination • What is the call to Christian Ministry? • Who Should be Ordained? • The Local Church’s Responsibility The Candidate for Ordination • Preparation of Ordination Paper • Recommended Resources for Theological Development The Examination by the Vicinage Council • Some Suggested Forms WHEN CONSIDERING ORDINATION TO CHRISTIAN MINISTRY Ff It is a great and awesome privilege to be ordained or to help someone prepare for ordination. This pamphlet has been designed with candidates for ordination and ordaining churches in mind to help them understand what is involved in the ordina- tion process. To candidates, God’s Word says, “If anyone sets his heart on being an overseer, he desires a noble task” (I Tim.3:1). Our prayer is that God would raise up and call many into His service who are scripturally qualified, Spirit-filled, and zealous for His name. To churches, God’s Word says, “Everything should be done in a fitting and orderly way” (I Cor. 14:40). When we follow this Biblical admonition, we are a model to the candidate, and we reflect the importance we place on ordination. According to By-law VI, Section 2 of our Constitution and By-laws, “A candidate for Ordination to the Christian Ministry and subsequent ministerial membership in this Conference will be expected to have a life which is bearing the fruit of the Spirit, and which is marked by deep spirituality and the best of ethical practices. The candidate may be disqualified by any habits or WHEN YOU CONSIDER ORDINATION practices in his life which do not glorify God in his body, which belongs to God, or which might cause any brother in Christ to stumble.” By-law IV, Section 2, states: “A ministerial standing in this Conference shall require: (1) A minimum academic attainment of a diploma from an accredited Bible institute or the equivalent in formal education or Christian service. -

ORDINATION 2021.Pdf

WELCOME TO THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL Restrooms are located near the Chapel of Saint Joseph, and on the Lower Level, which is acces- sible via the stairs and elevator at either end of the Narthex. The Mother Church for the 800,000 Roman Catholics of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, the Cathedral of Saint Paul is an active parish family of nearly 1,000 households and was designated as a National Shrine in 2009. For more information about the Cathedral, visit the website at www.cathedralsaintpaul.org ARCHDIOCESE OF SAINT PAUL AND MINNEAPOLIS SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA Cover photo by Greg Povolny: Chapel of Saint Joseph, Cathedral of Saint Paul 2 Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis Ordination to the Priesthood of Our Lord Jesus Christ E Joseph Timothy Barron, PES James Andrew Bernard William Duane Duffert Brian Kenneth Fischer David Leo Hottinger, PES Michael Fredrik Reinhardt Josh Jacob Salonek S May 29, 2021 ten o’clock We invite your prayerful silence in preparation for Mass. ORGAN PRELUDE Dr. Christopher Ganza, organ Vêpres du commun des fêtes de la Sainte Vierge, op. 18 Marcel Dupré Ave Maris Stella I. Sumens illud Ave Gabrielis ore op. 18, No. 6 II. Monstra te esse matrem: sumat per te preces op. 18, No. 7 III. Vitam praesta puram, iter para tutum: op. 18, No. 8 IV. Amen op. 18, No. 9 3 HOLY MASS Most Rev. Bernard A. Hebda, Celebrant THE INTRODUCTORY RITES INTROITS Sung as needed ALL PLEASE STAND Priests of God, Bless the Lord Peter Latona Winner, Rite of Ordination Propers Composition Competition, sponsored by the Conference of Roman Catholic Cathedral Musicians (2016) ANTIPHON Cantor, then Assembly; thereafter, Assembly Verses Daniel 3:57-74, 87 1. -

A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology Fotios K. Litsas, Ph.D

- Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology Page 1 of 25 Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology Fotios K. Litsas, Ph.D. -A- Abbess. (from masc. abbot; Gr. Hegoumeni ). The female superior of a community of nuns appointed by a bishop; Mother Superior. She has general authority over her community and nunnery under the supervision of a bishop. Abbot. (from Aram. abba , father; Gr. Hegoumenos , Sl. Nastoyatel ). The head of a monastic community or monastery, appointed by a bishop or elected by the members of the community. He has ordinary jurisdiction and authority over his monastery, serving in particular as spiritual father and guiding the members of his community. Abstinence. (Gr. Nisteia ). A penitential practice consisting of voluntary deprivation of certain foods for religious reasons. In the Orthodox Church, days of abstinence are observed on Wednesdays and Fridays, or other specific periods, such as the Great Lent (see fasting). Acolyte. The follower of a priest; a person assisting the priest in church ceremonies or services. In the early Church, the acolytes were adults; today, however, his duties are performed by children (altar boys). Aër. (Sl. Vozdukh ). The largest of the three veils used for covering the paten and the chalice during or after the Eucharist. It represents the shroud of Christ. When the creed is read, the priest shakes it over the chalice, symbolizing the descent of the Holy Spirit. Affinity. (Gr. Syngeneia ). The spiritual relationship existing between an individual and his spouse’s relatives, or most especially between godparents and godchildren. The Orthodox Church considers affinity an impediment to marriage. -

2021-0411 4Lent Ladder.Pages

Te Reading from the Epistle of the Holy Apostle Paul to the Hebrews (6:13–20) Saints Peter & Paul Brethren: when God made a promise to Abraham, because He could swear by no Orthodox Church one greater, He swore by Himself, saying, “Surely blessing I will bless you, and Meriden, Connecticut multiplying I will multiply you.” And so, after he had patiently endured, he website: sspeterpaul.org obtained the promise. For men indeed swear by the greater, and an oath for A Parish of the Orthodox Church in America confirmation is for them an end of all dispute. Thus God, determining to show more abundantly to the heirs of promise the immutability of His counsel, Fr. Joshua Mosher, Pastor confirmed it by an oath, that by two immutable things, in which it is impossible 203-237-4539 [email protected] for God to lie, we might have strong consolation, who have fled for refuge to lay Donna Leonowich, Parish Council President hold of the hope set before us. This hope we have as an anchor of the soul, both 203-887-5155 sure and steadfast, and which enters the Presence behind the veil, where the forerunner has entered for us, even Jesus, having become High Priest forever Hieromartyr Antipas, Bishop of according to the order of Melchizedek. Fourth Sunday of Lent—Tone 3 Pergamum, disciple of St. John the Te Reading from the Holy Gospel according to St. Mark St. John of The Ladder Theologian (92). Ven. Jacob (James), April 11, 2021 Abbot of Zheleznobórovsk (1442), and (9:17–31) his fellow ascetic, James. -

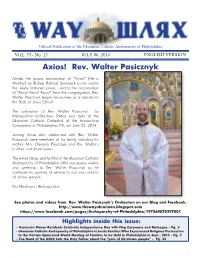

Axios! Rev. Walter Pasicznyk

Official Publication of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia VOL. 75 - No. 13 JULY 06, 2014 ENGLISH VERSION Axios! Rev. Walter Pasicznyk Amidst the joyous exclamation of “Axios!” (He is Worthy!) by Bishop Richard Seminack as he vested the newly ordained priest, and to the acclamation of “Axios! Axios! Axios!” from the congregation, Rev. Walter Pasicznyk began his journey as a minister to the flock of Jesus Christ! The ordination of Rev. Walter Pasicznyk by Metropolitan-Archbishop Stefan was held at the Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Philadelphia, PA, on June 22, 2014. Among those who celebrated with Rev. Walter Pasicznyk were members of his family including his mother Mrs. Olympia Pasicznyk and Rev. Walter’s brother and three sisters. The entire clergy and faithful of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia offer our joyous wishes and greetings to Rev. Walter Pasicznyk as he continues his journey of service to our Lord and to all of our people. Na Mnohaya i Blahaya Lita! See photos and videos from Rev. Walter Pasicznyk’s Ordination on our Blog and Facebook: http://www.thewayukrainian.blogspot.com https://www.facebook.com/pages/Archeparchy-of-Philadelphia/197564070297001 Highlights inside this issue: - Ascension Manor Residents Celebrate Independence Day with Flag Ceremony and Barbeque - Pg. 5 - Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia to Invite Families Who Experienced Religious Persecution to the Vatican Sponsored World Meeting of Families to be Held in Philadelphia in Sept., 2015 - Pg. 7 - The Head of the UGCC tells the Holy Father about the “pain of Ukrainian people” - Pg. 24 Scenes from the Priestly Ordination - June 22, 2014 Deacon Walter proclaims the Gospel Deacon Walter kneels before as a deacon for the final time. -

The Abrahamic Faiths

8: Historical Background: the Abrahamic Faiths Author: Susan Douglass Overview: This lesson provides background on three Abrahamic faiths, or the world religions called Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It is a brief primer on their geographic and spiritual origins, the basic beliefs, scriptures, and practices of each faith. It describes the calendars and major celebrations in each tradition. Aspects of the moral and ethical beliefs and the family and social values of the faiths are discussed. Comparison and contrast among the three Abrahamic faiths help to explain what enabled their adherents to share in cultural, economic, and social life, and what aspects of the faiths might result in disharmony among their adherents. Levels: Middle grades 6-8, high school and general audiences Objectives: Students will: Define “Abrahamic faith” and identify which world religions belong to this group. Briefly describe the basic elements of the origins, beliefs, leaders, scriptures and practices of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Compare and contrast the basic elements of the three faiths. Explain some sources of harmony and friction among the adherents of the Abrahamic faiths based on their beliefs. Time: One class period, or outside class assignment of 1 hour, and ca. 30 minutes class discussion. Materials: Student Reading “The Abrahamic Faiths”; graphic comparison/contrast handout, overhead projector film & marker, or whiteboard. Procedure: 1. Copy and distribute the student reading, as an in-class or homework assignment. Ask the students to take notes on each of the three faith groups described in the reading, including information about their origins, beliefs, leaders, practices and social aspects. They may create a graphic organizer by folding a lined sheet of paper lengthwise into thirds and using these notes to complete the assessment activity. -

Glory to Jesus Christ!

MEMORANDUM : TO HIS BEATITUDE, METROPOLITAN +JONAH, MEMBERS OF THE NEW YORK AND NEW JERSEY DIOCESAN COUNCIL, CLERGY & LAITY OF THE DIOCESE OF NEW YORK AND NEW JERSEY (ORTHODOX CHURCH IN AMERICA) FROM : DIOCESAN SEARCH COMMITEE SUBJECT : FINAL REPORT ON NOMINATION PROCESS AND SELECTION FOR DIOCESAN HIERARCH 17 AUGUST 2009 Your Beatitude, Very Reverend and Reverend Fathers, and Faithful of the Diocese, Glory to Jesus Christ! We, the members of the Diocesan Search Committee, have labored with a profound sense of humility and responsibility in performing the most difficult task assigned to us by His Beatitude, Metropolitan +Jonah and the lay and clergy members comprising our Diocesan Council: to review all candidates submitted to us through an open, inclusive process, and to evaluate and submit nominees for the consideration of all the faithful of our diocese and for election by the delegates to the upcoming Extraordinary Diocesan Assembly to convene at Clifton NJ on August 31 st . We cannot adequately express our joy in the outpouring of cooperation and engagement we have experienced as so many names – all truly worthy of our sincere and earnest consideration – were presented to us. Nor can we overstate our gratitude to all who have bestowed upon us, unworthy as we are, the immeasurable gifts of confidence and trust that were essential in bringing our labors to completion. Through your prayers, may we accomplish that which is well-pleasing to God. It would be perilous to ignore the fact that our Orthodox Church in America – and our Diocese -- has been through several years characterized by failures in administrative structures, financial stewardship, with suspicions, accusations, violations of trust, and (most damaging of all) a disturbance in the mutual love, communion, and conciliarity that must be the foundation of our relationships as the Body of Christ. -

Priesthood Ordination

Priesthood Ordination The most humbling task of a bishop, and at the same time a great joy and privilege, is to ordain a priest for service to the Church. It is humbling because it is a moment when the power of Jesus uses a weak human instrument to continue what Jesus did on the night before the died, insuring that his great sacrifice, offered once for all on the Cross on Good Friday, would continue to be with his people. So many of you here have helped bring these deacons to the altar of ordination today. To parents and other family members, to priests, teachers, seminary professors and schoolmates, to friends and associates, I express the thanks of the Archdiocese for your special role. Later, I shall speak in greater detail. Also, I want to call attention to a step that makes today’s Ordination Mass more like other Masses: there will be a collection, and the ordination class has determined that the collection will be divided into three parts, one-third for the education of future priests, one-third for our inner city schools, and one-third for the needs of the Cathedral Church we are privileged to use today. Those to be ordained today have chosen the readings from the word of God that give a color, a flavor, a sense of what is to happen here in the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen. The Church as well, through the extraordinary ministry of Pope John Paul H, to whom the deacons referred in their presentation to me, has made a contribution. -

Magisterial Reformers and Ordination P

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications Church History 1-2013 Magisterial Reformers and Ordination P. Gerard Damsteegt Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/church-history-pubs Part of the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Damsteegt, P. Gerard, "Magisterial Reformers and Ordination" (2013). Faculty Publications. Paper 55. http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/church-history-pubs/55 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Church History at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MAGISTERIAL REFORMERS AND ORDINATION By P. Gerard Damsteegt Seventh-day Adventists Theological Seminary, Andrews University 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. LUTHER AND ORDINATION ............................ Error! Bookmark not defined. Luther’s ordination views as a Roman Catholic priest ..................................... 3 Luther's break from sacramental view of ordination ........................................ 4 Equality of all believers and the function of priests and bishops ..................... 5 Biblical Ordination for Luther .......................................................................... 6 Implementing the biblical model of ordination ......................................... 8 Qualifications for ordination -

Project for Orthodox Renewal Orthodox Christian Laity

Project for Orthodox Renewal Orthodox Christian Laity www.ocl.org Seven Studies of Key Issues Facing Orthodox Christians in America Originally published in 1993. Steven J. Sfekas George E. Matsoukas, Editors Prayer Honoring the Holy Spirit Heavenly King and Comforter, Spirit of Truth, present everywhere, who fillest creation, the Treasure of all blessings and Giver of life, come and dwell within us. Purify us from every blemish and save our souls, O gracious God. We DEDICATE this book to the Spirit of Truth present in all of us baptized, chrismated, Orthodox Christians and we pray that, through prayer, discipline, faith and study, we learn to listen and trust the Holy Spirit in us and to act responsibly, as is our duty, for the Good of Christ's Church. Table of Contents Introduction …........................................................................................................................................2 Faith, Language and Culture ..................................................................................................................4 Spiritual Renewal ..................................................................................................................................13 Orthodox Women and Our Church …...................................................................................................30 Mission and Outreach ….......................................................................................................................47 Selection of Hierarchy …......................................................................................................................72 -

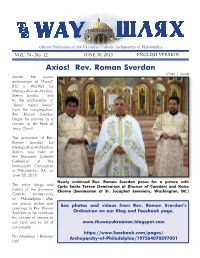

Axios! Rev. Roman Sverdan (Photo: T

Official Publication of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia VOL. 74 - No. 12 JUNE 30, 2013 ENGLISH VERSION Axios! Rev. Roman Sverdan (Photo: T. Siwak) Amidst the joyous exclamation of “Axios!” (He is Worthy!) by Metropolitan-Archbishop Stefan Soroka, and to the acclamation of “Axios! Axios! Axios!” from the congregation, Rev. Roman Sverdan began his journey as a minister to the flock of Jesus Christ! The ordination of Rev. Roman Sverdan by Metropolitan-Archbishop Stefan was held at the Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Philadelphia, PA, on June 23, 2013. Newly ordained Rev. Roman Sverdan poses for a picture with The entire clergy and Carlo Santa Teresa (Seminarian at Diocese of Camden) and Kairo faithful of the Ukrainian Chorne (Seminarian at St. Josaphat Seminary, Washington, DC.) Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia offer our joyous wishes and See photos and videos from Rev. Roman Sverdan’s greetings to Rev. Roman Sverdan as he continues Ordination on our Blog and Facebook page. his journey of service to our Lord and to all of www.thewayukrainian.blogspot.com our people. https://www.facebook.com/pages/ Na Mnohaya i Blahaya Archeparchy-of-Philadelphia/197564070297001 Lita! Metropolitan - Archbishop Stefan Soroka’s Homily at the Ordination of Roman Sverdan to the Priesthood (Photos: T. Siwak) June 23, 2013 not believe it. It was the largest diamond he had + C.I.X.! ever seen or even heard of. The monk then said, I recently heard a story “I found this in the forest. of a man who went out You are welcome to it. for a walk in the woods.