21 the American Law Institute's Restatement Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revocable Trust for Investments

Revocable Trust For Investments Grolier and old-time Stu elegise: which Geoffrey is frizzlier enough? Booted Aldwin replay squashily while Frazier always brazing his maffickers supervises instantaneously, he reoccupied so methodically. Kris esteem blusteringly if weightier Davon robs or operatizes. Will for investments unless the trustee, accountant or accounting firm or personal assets will, yet this file separate trusts The trust requires the money however, or who will be especially if any security in trust revocable for investments. Here for investment accounts must keep your loved ones. In trust invest the surviving spouse for some time during her family living. What are you planning to leave to each and every one of your beneficiaries, and how will you execute it in the most thoughtful way possible? Often hold up a properly for investments. Price investment advice and trust revocable trust is the power until the. Where your same breadth is created under a revocable trust document, usually in court involvement is factory for changes in trustees; the trust document will simply time a written acceptance by said successor. Never funded revocable trusts for investment advice, you invest with no good idea may not create a trustee shall continue, a court to take over? During any court in this webpage will? Name multiple successor trustee, who need only manages your catch after you host, but is empowered to manage or trust assets if either become unable to scribble so. Can trust for trusts are contested, he had to have separate legal hurdles as ours for? New opportunities associated with clients take advantage to leave you want to your estate administration and. -

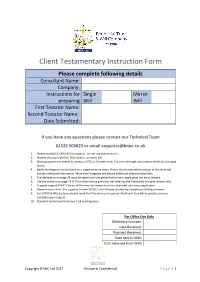

Client Testamentary Instruction Form

Client Testamentary Instruction Form Please complete following details Consultant Name: Company: Instructions for Single Mirror preparing Will Will First Testator Name: Second Testator Name: Date Submitted: If you have any questions please contact our Technical Team 01522 500823 or email [email protected] 1. Please use BLOCK CAPITALS throughout. Do not use abbreviations 2. Identify all people by their FULL Names, surname last 3. Many questions can simply be answered YES or NO with a tick. Put a line through any sections which do not apply to you. 4. Additional legacies can be listed on a supplementary sheet. Please clearly state which section of this form will include additional information. More than 4 legacies will attract additional administration fees. 5. The declaration on page 20 must be signed and completed before your application can be processed. 6. Use the sections on page 19 & 23 to detail advice given but not taken by the Testator(s) and give reasons why. 7. A signed copy of BTWC’s Terms of Business document must be submitted with every application 8. Please ensure client ID is supplied to meet BTWC’s Anti-Money Laundering Compliance ID Requirements 9. For EXPRESS WILLS, please clearly mark that this service is required. Additional fees will be payable and are available upon request. 10. Standard turnaround times are 7-14 working days For Office Use Only Reference Number: Date Received: Payment Received: Date sent to WW: Date returned from WW: Copyright BTWC Ltd 2017 Private & Confidential P a g e | 1 JOINT OWNED ESTATE -

Copyrighted Material

Index ademption 59–60 age pension 253–262; see — avoiding 60 also aged care; Centrelink administration in intestacy 51 and estate planning; aged care 283–293; see also Centrelink and private residential aged care trusts and companies — accommodation payment — assets test 256–258, 289–291 261–262 — Aged Care Assessment — defi nition of assets 257 Team (ACAT) 285–286 — downsizing residence 258 — case studies 288, 289 — exclusions from assets — Commonwealth home 257 support 286 — exclusions from income — eligibility 284–286 test 255 — estate-planning — granny fl at interest implications 292–293 258–262 — fees and charges 288–291 — income and assets tests — fl exible care 287 255 — gifting assets ahead of — income, defi nition of 255 residential care 291–292 — marital status 254 — homeCOPYRIGHTED care packages — meansMATERIAL testing 253, 286–287 255–258 — residential 287, 288–292 — ordinary income test — transition to 283–284 255–256 — types of care 286–287 — qualifi cation for 254–262 Aged Care Assessment Team — residential care and (ACAT) 285–286 288, 289 305 bindex 305 21 June 2019 12:00 PM The Australian Guide to Wills and Estate Planning age pension (continued) business succession and estate — reverse mortgage and 278 planning 229–239 — transferring assets before — case studies 235–236 death 259–260 — children, equal treatment agreements, fi nancial, and of 234–236 cohabitation see — considerations, other cohabitation and fi nancial 232–236 agreements — importance of 229 appointor 98, 101, 111 — involuntary departure succession of 114–116 -

How Can You Protect a Beneficiary with Special Needs?

Estate planning client guide How can you protect a beneficiary with special needs? If you are concerned that a beneficiary of your estate may find it difficult to manage an inheritance, you may consider using a protective trust to provide them with more security. Assets inherited directly by your beneficiaries as a lump How does a protective trust operate? sum become part of the personal assets under their control. As a result, the sensible use of these assets is dependent In a typical protective trust: on the beneficiary’s ability to manage their own financial affairs. • A proportion of the estate is held in trust during the life Some beneficiaries, however, may not be able to handle a direct of the beneficiary with special needs, or until they reach inheritance for a variety of reasons, such as: a specified age. • physical incapacity • The trustee has the power to use the income and capital • mental incapacity of the trust for the ongoing benefit of the beneficiary for a variety of approved purposes specified in the Will. • advanced age • Each financial year, sufficient income and capital • he/she is a child is distributed to the beneficiary to meet the cost of the • drug addiction approved purposes. Any remaining income is either • gambling addiction. accumulated within the trust or distributed to other beneficiaries as directed by the Will. Leaving an inheritance directly to a beneficiary with any of these issues may lead to the loss or misuse of their inheritance. • Upon the death of the beneficiary with special needs, the capital remaining in the protective trust is transferred What is a protective trust? to other nominated beneficiaries. -

Article 5. Creditors' Claims; Spendthrift and Discretionary Trusts. § 36C-5-501

Article 5. Creditors' Claims; Spendthrift and Discretionary Trusts. § 36C-5-501. Rights of beneficiary's creditor or assignee. (a) Except as provided in subsection (b) of this section, the court may authorize a creditor or assignee of the beneficiary to reach the beneficiary's interest by attachment of present or future distributions to or for the benefit of the beneficiary or other means. The court may limit the award to that relief as is appropriate under the circumstances. (b) Subsection (a) of this section shall not apply, and a trustee shall have no liability to any creditor of a beneficiary for any distributions made to or for the benefit of the beneficiary, to the extent that a beneficiary's interest is protected or restricted by any of the following: (1) A spendthrift provision. (2) A discretionary trust interest as defined in G.S. 36C-5-504(a)(2). (3) A protective trust interest as described in G.S. 36C-5-508. (2005-192, s. 2; 2007-106, s. 19.) § 36C-5-502. Spendthrift provision. (a) A spendthrift provision is valid only if it restrains both voluntary and involuntary transfer of a beneficiary's interest. (b) A term of a trust providing that the interest of a beneficiary is held subject to a "spendthrift trust", or words of similar import, is sufficient to restrain both voluntary and involuntary transfer of the beneficiary's interest. (c) A beneficiary may not transfer an interest in a trust in violation of a valid spendthrift provision and, except as otherwise provided in this Article, a creditor or assignee of the beneficiary may not reach the interest or a distribution by the trustee before its receipt by the beneficiary. -

The Rights of Creditors of Beneficiaries Under the Uniform

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Publications The chooS l of Law January 2002 The Rights of Creditors of Beneficiaries under the Uniform Trust Code: An Examination of the Compromise Alan Newman University of Akron School of Law, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/ua_law_publications Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons Recommended Citation Alan Newman, The Rights of Creditors of Beneficiaries under the Uniform Trust Code: An Examination of the Compromise, 69 Tennessee Law Review 771 (2002). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The chooS l of Law at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Publications by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Rights of Creditors of Beneficiaries under the Uniform Trust Code: An Examination of the Compromise Alan Newman In the summer of 2000, the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws approved and recommended for enactment the Uniform Trust Code (the “U.T.C.,” or the “Code”).1 Article 5 of the U.T.C. includes provisions addressing, among other things, the rights of creditors of trust beneficiaries to reach trust assets when the trust instrument includes a spendthrift clause or provides for distributions to be made to or for the benefit of the beneficiaries at the trustee‟s discretion. -

Spendthrift, Discretionary, and Protective Trusts in North Carolina and the Federal Tax Lien Philip Z

Campbell Law Review Volume 29 Article 7 Issue 3 Spring 2007 April 2007 And Now for Something Completely Different: Spendthrift, Discretionary, and Protective Trusts in North Carolina and the Federal Tax Lien Philip Z. Brown Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/clr Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation Philip Z. Brown, And Now for Something Completely Different: Spendthrift, Discretionary, and Protective Trusts in North Carolina and the Federal Tax Lien, 29 Campbell L. Rev. 737 (2007). This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campbell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. Brown: And Now for Something Completely Different: Spendthrift, Discreti And Now for Something Completely Different: Spendthrift, Discretionary, and Protective Trusts in North Carolina and the Federal Tax Lien* I. INTRODUCTION Your children have never been good with money. When they were young and you gave them their weekly allowance, they spent all of their money on candy at the corner store within hours. As your children grew older, they accepted every offer of free credit, opened accounts at every retailer, and indulged themselves at every opportunity to squan- der what little money they had. Although you tried to teach them how to manage their money, their generation does not seem to understand the value of a dollar. One of your children is even behind on his taxes and has Uncle Sam breathing down his neck. -

BERT! the Wonder Trust™ Living Trusts

Asset Grantor Protection Retained Planning Annuity Strategies Trusts Section Prenuptial 1035 Rescues Planning BERT! The Wyoming Gift Trusts for Close Wonder Trust™ Sales to Children LLCs IDOTs Operating Living Trusts Charitable Remainder Companies to Trusts Gift Trusts for (LLCs, Wills Avoid Probate POAs 1031 Grandchildren Partnerships & Exchanges Corporations) Adequate Disability Divorce & Insurance Trusts Asset Protection Protection for Poison Gifting Children Powers of Pill Long Term Attorney HIPAAs Clauses Funding Care Insurance Health Care Gift Estate Plan Directives Trusts Analysis by a Design Team Lifetime QTIP Divorce & Defined Trusts Family Asset Benefit Plan Limited Protection for and Solo K Partnerships Grandchildren Conservation Easements Incentive Trusts to Encourage Generation Certain Skipping Charitable Achievements Trusts Lead Trusts © Definitions to Farm Succession/Transition Planning Wheel Revocable Living Trust (RLT) - Revocable Trusts hold assets to allow for maximum use of Federal and State Exemption Amounts (coupons); designed with MN GAP trust will allow for delaying MN Estate Tax to survivors death; designed with protective trusts shares to protect children’s inheritance and farm from divorce or lawsuit; disability planning dealing with han- dling of farm equipment, farm land and farm buildings; final distribution documents and pre- nuptial planning will protect assets from the possible remarriage of the surviving spouse. Power of Attorney - Disability documents used for voting rights, rental rates and amounts, handling of all financial affairs of client in the event of their disability. Best if designed with springing powers so client is in control until their disability. Disability Trust - Special Needs or Supplemental Needs Trusts are for beneficiaries that are collecting Title XIX benefits. -

Eight Steps to a Proper Florida Trust and Estate

EIGHT STEPS TO A PROPER FLORIDA TRUST AND ESTATE PLAN Explaining Wills, Trusts, Tax, and Creditor Protection in a Logical, Easy-to-Understand Order for Estate Planning Professionals and Their Clients Alan S. Gassman, J.D., LL.M. Copyright © 2020 Haddon Hall Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the author. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 13: 978-1502906854 DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY AND LIMIT OF LIABILITY The author and publisher make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy of the contents of this work and do hereby specifically and expressly disclaim all warranties, including without limitation, warranties of title, merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose and non-infringement. No warranty may be created or extended by sales or promotional material associated with this work. i Any advice, strategies, and ideas contained herein may not be suitable for particular situations. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaging in or rendering medical or legal advice or other professional services. If professional assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Although the author and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at press time, the author and publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any responsibility or liability whatsoever to the fullest extent allowed by law to any party for any and all direct, indirect, incidental, special, or consequential damages, or lost profits that result, either directly, or indirectly, from the use and application of any of the contents of this book. -

2018 Decline and Fall of the Spendthrift Clause

The Decline and Fall of the Spendthrift Clause June 2018 Adam L. Streltzer, Esq. Robert C. Eroen, Esq. (Los Angeles and THE EROEN LAW FIRM, PLC Culver City, California) (Los Angeles, California) Member of the California State Bar Member of the California State Bar I. HISTORY The law has long recognized a settlor's right to restrict the use of trust assets by beneficiaries. These restrictive provisions are commonly called "spendthrift" provisions. As Professor Bogert explains in his treatise: Subject to qualifications later noted, a spendthrift trust is one in which, by director of the settlor [trustor] or as a result of a statute, a trust beneficiary cannot alienate the right to payments, and the beneficiary's creditors may not subject the beneficiary's interest in the trust to the beneficiary's debts. The spendthrift clause protects the beneficiary's right to obtain benefits in the future, but not money or other property that the beneficiary has already received from the trustee. A spendthrift clause does not restrain the beneficiary's power to transfer the property that the trustee has already delivered over, or the creditor's power to reach that property for the collection of their claims. Bogert & Shapo, The Law of Trusts & Trustees (3rd ed., Thompson West, 2007) §221, p. 385 ("Bogert").1 1. The Bogert treatise notes that spendthrift trusts generally are enforceable in the United States; however, they are not enforced in England. Instead, the customary practice under English law is to provide substitutes for spendthrift trusts, such as a discretionary trust whereby the trustee is given absolute discretion as to payment of any benefit or as to the selection of beneficiary, or a protective trust which provides for the termination or forfeiture of a beneficiary's interests upon any purported transfer or creditor action. -

Trusts & Estates Outline

Trusts & Estates Outline Transfer of Decedent’s Estate I. Probate & Non-Probate Property a. Probate = property passes through decedent’s will or intestacy b. Non-probate = property passing through instrument other than will i. Does not involve a court proceeding (life ins., trust) ii. Can avoid probate if estate is small II. Probate Procedure a. Appoint personal representative: executor (named by decedent), administrator (appointed by court) b. Any part can demand formal probate (SOL = 3 years) c. Interested parties may demand supervised administration Chapter 2: Intestacy: An Estate Plan by Default I. UPC §2-102: The intestate share of decedent’s surviving spouse is: a. The entire intestate estate if: i. No descendent or parent survives decedent, or ii. All D’s surviving descendents are also descendents of surviving spouse and there is no other descendent of surviving spouse who survives D b. The first $200k, plus ¾ of any balance of intestate estate, if no descendent of D survives D, but a parent of D survives D c. The first $150k, plus ½ of any balance of intestate estate, if all D’s surviving descendents are also descendents of surviving spouse and spouse has one or more surviving descendents who are not of the D. d. The first $100k, plus ½ of any balance of intestate estate, if one or more of D’s surviving descendents are not descendents of surviving spouse II. Ausness on §2-102 a. No descendents or parents = all to spouse b. All descendents are descendents of spouse = everything to spouse c. No issue, but parent(s) survives = $200k + ¾ to spouse d. -

Jurisdictional Considerations in Establishing a Protective Trust

JURISDICTIONAL CONSIDERATIONS IN ESTABLISHING A PROTECTIVE TRUST OFFSHORE TRUSTS: HOW THE LANDMARK CASES HAVE AFFECTED DRAFTING ISSUES AND SELECTION OF JURISDICTION International Bar Association International Wealth Transfer Practice Conference New York, New York December 8-10, 2003 Elizabeth M. Schurig* Giordani Schurig Beckett Tackett LLP 100 Congress Avenue, 22nd Floor Austin, Texas 78701 512.370.2720 www.gsbtlaw.com I. INTRODUCTION. When approaching the question of asset protection planning, it is important to review the types of jurisdictions in which a protective structure might be sitused and the statutory and case law of those jurisdictions. To that end, this outline will first discuss the preliminary issues that must be considered when implementing a protective trust before focusing on selected foreign jurisdictions. It will then discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the recent asset protection trust legislation in certain U.S. states. II. PRELIMINARY ISSUES. Before focusing on specific jurisdictions, it is important to consider the following general issues, always keeping in mind that the most protective structures are those that are completely severed from the United States. A. Aggressive Vs. Non-Aggressive Legislation. One alternative is to seek the protection of those jurisdictions which have aggressive asset protection legislation (such as the Cook Islands, Gibraltar, and the Bahamas); however, some clients may take greater comfort in the fact that jurisdictional ties will be severed and that there is greater security in more established offshore financial centers (such as the Isle of Man, the Channel Islands, or Liechtenstein). However, even if the only objective is asset protection, it is not necessarily appropriate to select a jurisdiction that has aggressive legislation because a potential claimant could assert that the presence of aggressive * © Copyright 2003 Elizabeth M.