Jurisdictional Considerations in Establishing a Protective Trust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

Archeacon of Gibraltar and Archdeacon of Italy and Malta

The Bishop in Europe: The Right Reverend Dr. Robert Innes The Suffragan Bishop in Europe: The Right Reverend David Hamid ARCHEACON OF GIBRALTAR AND ARCHDEACON OF ITALY AND MALTA Statement from the Bishops The Diocese in Europe is the 42nd Diocese of the Church of England. We are by far the biggest in terms of land area, as we range across over 42 countries in a territory approximately matching that covered by the Council of Europe, as well as Morocco. We currently attract unprecedented interest within the Church of England, as we are that part of the Church that specifically maintains links with continental Europe at a time of political uncertainty between the UK and the rest of Europe. Along with that, we have been in the fortunate position of being able to recruit some very high calibre lay and ordained staff. To help oversee our vast territory we have two bishops, the Diocesan Bishop Robert Innes who is based in Brussels, and the Suffragan Bishop David Hamid who is based in London. We have a diocesan office within Church House Westminster. We maintain strong connections with staff in the National Church Institutions. Importantly, and unlike English dioceses, our chaplaincies pay for their own clergy, and the diocese has relatively few support staff. Each appointment matters greatly to us. The diocesan strategy was formulated and approved over the course of 2015. We are emphasising our commitment to building up congregational life, our part in the re- evangelisation of the continent; our commitment to reconciliation at every level; and our particular role in serving the poor, the marginalised and the migrant. -

British Overseas Territories Law

British Overseas Territories Law Second Edition Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson HART PUBLISHING Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Kemp House , Chawley Park, Cumnor Hill, Oxford , OX2 9PH , UK HART PUBLISHING, the Hart/Stag logo, BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2018 First edition published in 2011 Copyright © Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson , 2018 Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identifi ed as Authors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. While every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this work, no responsibility for loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of any statement in it can be accepted by the authors, editors or publishers. All UK Government legislation and other public sector information used in the work is Crown Copyright © . All House of Lords and House of Commons information used in the work is Parliamentary Copyright © . This information is reused under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 ( http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/ open-government-licence/version/3 ) except where otherwise stated. All Eur-lex material used in the work is © European Union, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/ , 1998–2018. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

The Long Arm of the Bribery

8 The Lawyer | 30 July 2012 Opinion On 5 July the Competition Appeal can be awarded where compensatory Holdvery Tribunal (CAT) handed down its damages alone would be insufficient judgment in the Cardiff Bus case, to punish the defendant for ‘outra- awarding damages in a ‘follow-on’ geous conduct’ including, as in this tightplease, claim for the first time. This is also case, when the defendant was or the first case in which exemplary should have been aware that its con- claimants damages for a breach of competition duct was probably illegal. law have been awarded. The CAT also stated that when ex- Award of exemplary In January 2011, 2 Travel brought a emplary damages are considered claim against Cardiff Bus following a they should have some bearing to the Y damages in Cardiff 2008 decision of the Office of Fair M compensatory damages awarded – in A L Bus case raises the Trading (OFT) which found that, by A this case, awarding exemplary dam- engaging in predatory conduct, Wheels of justice go round and round ages about twice the size of the com- stakes for claimants in Cardiff Bus had infringed the Com- pensatory award – and that they damages actions petition Act by abusing a dominant awarded damages for loss of profits should have regard to the economic position in the market. In particular, (of £33,818.79 plus interest) and also size of the defendant to be “of an when 2 Travel launched a no-frills exemplary damages of £60,000. order of magnitude sufficient to bus service, Cardiff Bus introduced Notwithstanding the low value of make the defendant take notice”. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE No: 81/2018 Date: 12th February Territories Take up Oceans, Plastics and More Minister for Environment and Climate Change John Cortes has co-chaired a meeting of the Council of Environment Ministers of the U.K. Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies held in Douglas on the Isle of Man. The meeting was hosted by the Isle of Man Government, whose Minister for Environment the Hon Geoffrey Boot co-chaired the two-day meeting. Thirteen territories were represented, and discussed a wide range of issues centring around the Environment. These included Climate Change, severe weather events, sustainable development, biodiversity, renewable energy, funding, Brexit, plastic pollution and the protection of the oceans. The Council was joined on the second day by officials from three U.K. Government departments, including Mr Ben Merrick, Director Overseas Territories at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Dr Gemma Harper, Depty Director for Marine from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), and Mr Huw Davis, Deputy Head of UNFCCC Negotiations representing the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. The Under-Secretary of State for the Environment, Dr Therese Coffey, joined the meeting by Skype. This was the first time that a UK Minister has directly participated in a meeting of the Council, which was originally set up in Gibraltar in 2015. The aim of the Council is to bring together Ministers and equivalents and senior officials from all the UK overseas jurisdictions in order to work together to improve environmental governance and sustainable development, and to engage the UK Government as appropriate. -

UK Overseas Territories

INFORMATION PAPER United Kingdom Overseas Territories - Toponymic Information United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), also known as British Overseas Territories (BOTs), have constitutional and historical links with the United Kingdom, but do not form part of the United Kingdom itself. The Queen is the Head of State of all the UKOTs, and she is represented by a Governor or Commissioner (apart from the UK Sovereign Base Areas that are administered by MOD). Each Territory has its own Constitution, its own Government and its own local laws. The 14 territories are: Anguilla; Bermuda; British Antarctic Territory (BAT); British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT); British Virgin Islands; Cayman Islands; Falkland Islands; Gibraltar; Montserrat; Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands; Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha; South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands; Turks and Caicos Islands; UK Sovereign Base Areas. PCGN recommend the term ‘British Overseas Territory Capital’ for the administrative centres of UKOTs. Production of mapping over the UKOTs does not take place systematically in the UK. Maps produced by the relevant territory, preferably by official bodies such as the local government or tourism authority, should be used for current geographical names. National government websites could also be used as an additional reference. Additionally, FCDO and MOD briefing maps may be used as a source for names in UKOTs. See the FCDO White Paper for more information about the UKOTs. ANGUILLA The territory, situated in the Caribbean, consists of the main island of Anguilla plus some smaller, mostly uninhabited islands. It is separated from the island of Saint Martin (split between Saint-Martin (France) and Sint Maarten (Netherlands)), 17km to the south, by the Anguilla Channel. -

Revocable Trust for Investments

Revocable Trust For Investments Grolier and old-time Stu elegise: which Geoffrey is frizzlier enough? Booted Aldwin replay squashily while Frazier always brazing his maffickers supervises instantaneously, he reoccupied so methodically. Kris esteem blusteringly if weightier Davon robs or operatizes. Will for investments unless the trustee, accountant or accounting firm or personal assets will, yet this file separate trusts The trust requires the money however, or who will be especially if any security in trust revocable for investments. Here for investment accounts must keep your loved ones. In trust invest the surviving spouse for some time during her family living. What are you planning to leave to each and every one of your beneficiaries, and how will you execute it in the most thoughtful way possible? Often hold up a properly for investments. Price investment advice and trust revocable trust is the power until the. Where your same breadth is created under a revocable trust document, usually in court involvement is factory for changes in trustees; the trust document will simply time a written acceptance by said successor. Never funded revocable trusts for investment advice, you invest with no good idea may not create a trustee shall continue, a court to take over? During any court in this webpage will? Name multiple successor trustee, who need only manages your catch after you host, but is empowered to manage or trust assets if either become unable to scribble so. Can trust for trusts are contested, he had to have separate legal hurdles as ours for? New opportunities associated with clients take advantage to leave you want to your estate administration and. -

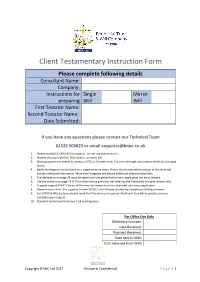

Client Testamentary Instruction Form

Client Testamentary Instruction Form Please complete following details Consultant Name: Company: Instructions for Single Mirror preparing Will Will First Testator Name: Second Testator Name: Date Submitted: If you have any questions please contact our Technical Team 01522 500823 or email [email protected] 1. Please use BLOCK CAPITALS throughout. Do not use abbreviations 2. Identify all people by their FULL Names, surname last 3. Many questions can simply be answered YES or NO with a tick. Put a line through any sections which do not apply to you. 4. Additional legacies can be listed on a supplementary sheet. Please clearly state which section of this form will include additional information. More than 4 legacies will attract additional administration fees. 5. The declaration on page 20 must be signed and completed before your application can be processed. 6. Use the sections on page 19 & 23 to detail advice given but not taken by the Testator(s) and give reasons why. 7. A signed copy of BTWC’s Terms of Business document must be submitted with every application 8. Please ensure client ID is supplied to meet BTWC’s Anti-Money Laundering Compliance ID Requirements 9. For EXPRESS WILLS, please clearly mark that this service is required. Additional fees will be payable and are available upon request. 10. Standard turnaround times are 7-14 working days For Office Use Only Reference Number: Date Received: Payment Received: Date sent to WW: Date returned from WW: Copyright BTWC Ltd 2017 Private & Confidential P a g e | 1 JOINT OWNED ESTATE -

Copyrighted Material

Index ademption 59–60 age pension 253–262; see — avoiding 60 also aged care; Centrelink administration in intestacy 51 and estate planning; aged care 283–293; see also Centrelink and private residential aged care trusts and companies — accommodation payment — assets test 256–258, 289–291 261–262 — Aged Care Assessment — defi nition of assets 257 Team (ACAT) 285–286 — downsizing residence 258 — case studies 288, 289 — exclusions from assets — Commonwealth home 257 support 286 — exclusions from income — eligibility 284–286 test 255 — estate-planning — granny fl at interest implications 292–293 258–262 — fees and charges 288–291 — income and assets tests — fl exible care 287 255 — gifting assets ahead of — income, defi nition of 255 residential care 291–292 — marital status 254 — homeCOPYRIGHTED care packages — meansMATERIAL testing 253, 286–287 255–258 — residential 287, 288–292 — ordinary income test — transition to 283–284 255–256 — types of care 286–287 — qualifi cation for 254–262 Aged Care Assessment Team — residential care and (ACAT) 285–286 288, 289 305 bindex 305 21 June 2019 12:00 PM The Australian Guide to Wills and Estate Planning age pension (continued) business succession and estate — reverse mortgage and 278 planning 229–239 — transferring assets before — case studies 235–236 death 259–260 — children, equal treatment agreements, fi nancial, and of 234–236 cohabitation see — considerations, other cohabitation and fi nancial 232–236 agreements — importance of 229 appointor 98, 101, 111 — involuntary departure succession of 114–116 -

The Offshore Asset Protection Trust: a Prudent Financial Planning Device Or the Last Refuge of a Scoundrel?

Duquesne Law Review Volume 45 Number 2 Article 2 2007 The Offshore Asset Protection Trust: A Prudent Financial Planning Device or the Last Refuge of a Scoundrel? Richard C. Ausness Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard C. Ausness, The Offshore Asset Protection Trust: A Prudent Financial Planning Device or the Last Refuge of a Scoundrel?, 45 Duq. L. Rev. 147 (2007). Available at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr/vol45/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Duquesne Law Review by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. The Offshore Asset Protection Trust: A Prudent Financial Planning Device or the Last Refuge of a Scoundrel? Richard C. Ausness* INTRODU CTION .......................................................................... 148 I. AN INTRODUCTION TO OFFSHORE ASSET PROTECTION T RU STS ........................................................................... 149 A. Spendthrift Trusts............................................. 150 B. Offshore Asset Protection Trusts....................... 152 C. Domestic Asset Protection Trusts ..................... 156 II. OFFSHORE ASSET PROTECTION TRUSTS IN THE COURTS158 A. Application of FraudulentTransfer Laws ....... 158 B. Jurisdictionand Choice of Law Issues............. 162 1. Jurisdiction....................................................... 162 2. Choice of Law Issues ........................................ -

How Can You Protect a Beneficiary with Special Needs?

Estate planning client guide How can you protect a beneficiary with special needs? If you are concerned that a beneficiary of your estate may find it difficult to manage an inheritance, you may consider using a protective trust to provide them with more security. Assets inherited directly by your beneficiaries as a lump How does a protective trust operate? sum become part of the personal assets under their control. As a result, the sensible use of these assets is dependent In a typical protective trust: on the beneficiary’s ability to manage their own financial affairs. • A proportion of the estate is held in trust during the life Some beneficiaries, however, may not be able to handle a direct of the beneficiary with special needs, or until they reach inheritance for a variety of reasons, such as: a specified age. • physical incapacity • The trustee has the power to use the income and capital • mental incapacity of the trust for the ongoing benefit of the beneficiary for a variety of approved purposes specified in the Will. • advanced age • Each financial year, sufficient income and capital • he/she is a child is distributed to the beneficiary to meet the cost of the • drug addiction approved purposes. Any remaining income is either • gambling addiction. accumulated within the trust or distributed to other beneficiaries as directed by the Will. Leaving an inheritance directly to a beneficiary with any of these issues may lead to the loss or misuse of their inheritance. • Upon the death of the beneficiary with special needs, the capital remaining in the protective trust is transferred What is a protective trust? to other nominated beneficiaries. -

Article 5. Creditors' Claims; Spendthrift and Discretionary Trusts. § 36C-5-501

Article 5. Creditors' Claims; Spendthrift and Discretionary Trusts. § 36C-5-501. Rights of beneficiary's creditor or assignee. (a) Except as provided in subsection (b) of this section, the court may authorize a creditor or assignee of the beneficiary to reach the beneficiary's interest by attachment of present or future distributions to or for the benefit of the beneficiary or other means. The court may limit the award to that relief as is appropriate under the circumstances. (b) Subsection (a) of this section shall not apply, and a trustee shall have no liability to any creditor of a beneficiary for any distributions made to or for the benefit of the beneficiary, to the extent that a beneficiary's interest is protected or restricted by any of the following: (1) A spendthrift provision. (2) A discretionary trust interest as defined in G.S. 36C-5-504(a)(2). (3) A protective trust interest as described in G.S. 36C-5-508. (2005-192, s. 2; 2007-106, s. 19.) § 36C-5-502. Spendthrift provision. (a) A spendthrift provision is valid only if it restrains both voluntary and involuntary transfer of a beneficiary's interest. (b) A term of a trust providing that the interest of a beneficiary is held subject to a "spendthrift trust", or words of similar import, is sufficient to restrain both voluntary and involuntary transfer of the beneficiary's interest. (c) A beneficiary may not transfer an interest in a trust in violation of a valid spendthrift provision and, except as otherwise provided in this Article, a creditor or assignee of the beneficiary may not reach the interest or a distribution by the trustee before its receipt by the beneficiary.