CHAPTER SIX CONTEXT of the Ksipp Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profile: City of Ekurhuleni

2 PROFILE: CITY OF EKURHULENI PROFILE: CITY OF EKURHULENI 3 CONTENT 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 5 2. Introduction: Brief Overview............................................................................. 6 2.1 Historical Perspective ............................................................................................... 6 2.1 Location ................................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Spatial Integration ................................................................................................. 8 3. Social Development Profile............................................................................... 9 3.1 Key Social Demographics ........................................................................................ 9 3.2 Health Profile .......................................................................................................... 12 3.3 COVID-19 .............................................................................................................. 13 3.4 Poverty Dimensions ............................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Distribution .......................................................................................................... 15 3.4.2 Inequality ............................................................................................................. 16 3.4.3 Employment/Unemployment -

Gauteng Germiston South Sheriff Service Area of Ekurhuleni Central Magisterial District Germiston South Sheriff Service Area Of

!C ! ^ ! !C ^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! !C ! ! $ ^ ! ! !C ! ^ ! !C !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C !ñ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! !C ! $ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! !C $ ! ! ^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !. ! ^ ! !C ñ ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! ^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! !C ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! ! ^ ! ! ^ ! ! ! ^ ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! !C ! ! ^ ! !C ! ! ! ! ñ !C ! !. ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ñ !. ! ^ ! ! ! ! ! !C ! !C ! $!C ! ! !. ^ !. ^ ! !C ^ ! ! !C !C ! ! ! !C ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! !C ! !. ^ ! $ ^ !C ! ! !C ^ ! ñ!C !. ! ! !C ^ ! ! !. $ !C !C ! ! ! ! ! ! !C ! !C !. ! ñ ! ! ^ ! !C $ ^ ! ^ ! $ ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! !C ! !. ñ ! ! ! ^ !C ! ! !C ! ! ! !C !C ! !C ! ! !C !C ! ! !C ! ! ! ! !C ! ! ! ! !C !C ! ^ ! ! $ !C ! !C ! !C !. ^ ! $ ! !C ! ! ! !C !C ! ! -

For More Information, Contact the Office of the Hod: • 011 999 3845/6194 Introduction

The City of Ekurhuleni covers an extensive area in the eastern region of Gauteng. This extensive area is home to approximately 3.1 million and is a busy hub that features the OR Tambo International Airport, supported by thriving business and industrial activities. Towns that make up the City of Ekurhuleni are Greater Alberton, Benoni, Germiston, Duduza, Daveyton, Nigel, Springs, KwaThema, Katlehong, Etwatwa, Kempton Park, Edenvale, Brakpan, Vosloorun, Tembisa, Tsakane, and Boksburg. Ekurhuleni region accounts for a quarter of Gauteng’s economy and includes sectors such as manufacturing, mining, light and heavy industry and a range of others businesses. Covering such a large and disparate area, transport is of paramount importance within Ekurhuleni, in order to connect residents to the business areas as well as the rest of Gauteng and the country as a whole. Ekurhuleni is highly regarded as one of the main transport hubs in South Africa as it is home to OR Tambo International Airport; South Africa’s largest railway hub and the Municipality is supported by an extensive network of freeways and highways. In it features parts of the Maputo Corridor Development and direct rail, road and air links which connect Ekurhuleni to Durban; Cape Town and the rest of South Africa. There are also linkages to the City Deep Container terminal; the Gautrain and the OR Tambo International Airport Industrial Development Zone (IDZ). For more information, contact the Office of the HoD: • 011 999 3845/6194 Introduction The City of Ekurhuleni covers an extensive area in the eastern region of Gauteng. This extensive area is home to approximately 3.1 million and is a busy hub that features the OR Tambo International Airport, supported by thriving business and industrial activities. -

Nigel Ward Profile Population

NIGEL WARD PROFILE POPULATION The Estimated Residents: 72517 WARD COUNCILLORS WARD COUNCILORS WARDS Mr Wally Labuschagne Ward 88 Ms Tiny Mabena Ward 98 FACILITIES FACILITIES QUANTITY Schools 9 Police Stations 3 Medical Institutions 3 Libraries 3 Multi-Purpose 0 Parks 13 SASSA 1 Mall 1 Swimming Pools 2 Halls 3 Shopping Centers 3 1.1 Energy DEPARTMENT ACHIEVEMENTS Energy Vosterskroon Substation - To improve quality of supply - Streetlights along Nigel/Springs Road - Upgrading of cables between Munic and Standard street - Upgraded supply between Nicole Rd and Pieter Wessels DEPARTMENT: ENERGY ISSUES RAISED (PREVIOUS IMBIZO FEB13) RESPONSE (FEEDBACK) They filled forms for electricity, but no respond.( 2128 The department will install but not in this financial year Slovo Park Ext3) 2013/2014 and still waiting for town proclamation to be completed. Need electricity & High mast is not working. (995 Snake Four High mast were erected and all in working Park, Alra-Park) condition. Why there is a delay on issues like installation of Contractor on site for RDP houses, Alra Park Ext 3 electricity in houses? In Alrapark Dunnottar residence request Apollo lights. Appollo lights were installed and in working condition. Continuous power outages in Dunnorttar Eskom has sorted out the problem of power outages DEPARTMENT: ENERGY DEPARTMENT CHALLENGES Energy Streetlight Maintenance as there is only 1 attendant for the whole area 1.2 Water and Sanitation DEPARTMENT ACHIEVEMENTS Water and Sanitation - Replacement of 150mm Ac pipe with a Upvc pipe in Vorsterkroon, Nigel. Almost 300 m of pipe was replaced. 2 New above ground hydrant were also installed. - Replacement of 150mm Ac pipe with a Upvc pipe in Vorsterkroon, Nigel. -

General Notice 1. 2. 3. 4. Applications Received for A

STAATSKOERANT, 8 NOVEMBER 2006 No.29371 3 GENERAL NOTICE NOTICE 1569 OF 2006 ~ e ”- APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR A FOUR YEAR COMMUNITY SOUND BROADCASTING LICENCE IFM 102.2 RADIO STATION AND KATHORUS COMMUNITY RADIO 1. The Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (“the Authority”) hereby gives notice that, pursuant to the invitation published in Government Gazette No. 29127 dated 14 August 2006, Notice No. 1108, two applications were received from IFM 102.2 MHz Radio Station, broadcasting as IFM 102.2 and Kathorus Community Radio Station, broadcasting as Kathorus Community Radio. The details of the applications are contained in the schedule below. 2. The applications are available and open for inspection by interested persons in the Authority’s library during the Authority’s normal office hours. 3. Interested persons are invited to lodge written representations in relation to the applications by no later than 8 December 2006. Representations must be directed to Thabo Ndhlovu, Manager: Licensing, at The Licensing Unit, Broadcasting Division, Independent Communications Authority of South Africa at Block D, Pinmill Farm, 164 Katherine Street, Sandton, Johannesburg or Private Bag X 10002, Sandton, 2146 or by fax no. (011) 448 2186. 4. The persons who make such representations must indicate in their written representations whether they require an opportunity to make oral representations to the Authority. Persons who submit representations in terms hereof shall, when submitting such representations, provide proof to the satisfaction of the Authority that a copy of the representations submitted has been sent by registered mail or by facsimile, or delivered to the following: i. In respect of IFM 102.2 to Dave Hammond at Mittal Steel Works, Employment Building, Delfos Blvd, Vanderbijlpark or P 0 Box 2, Vanderbijlpark, 1900 or by fax no. -

Gauteng Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (GDARD)

BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT [REGULATION 22(1)] Gauteng Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (GDARD) Basic Assessment Report in terms of the National Environmental Management Act, 1998 (Act No. 107 of 1998), as amended, and the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations, 2010 (Version 1) List of all organs of state and State Departments where the draft report has been submitted, their full contact details and contact person Kindly note that: 1. This Basic Assessment Report is the standard report required by GDARD in terms of the EIA Regulations, 2010. 2. This application form is current as of 2 August 2010. It is the responsibility of the EAP to ascertain whether subsequent versions of the form have been published or produced by the competent authority. 3. A draft Basic Assessment Report must be submitted to all State Departments administering a law relating to a matter likely to be affected by the activity to be undertaken. The draft reports must be submitted to the relevant State Departments and on the same day, two CD’s of draft reports must also be submitted to the Competent Authority (GDARD) with a signed proof of such submission of draft report to the relevant State Departments. 4. The report must be typed within the spaces provided in the form. The size of the spaces provided is not necessarily indicative of the amount of information to be provided. The report is in the form of a table that can extend itself as each space is filled with typing. 5. Selected boxes must be indicated by a cross and, when the form is completed electronically, must also be highlighted. -

Day 2 : Approaches to NDPG Projects Tshiwo Yenana 30 October 2007

TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Day 2 : Approaches to NDPG Projects Tshiwo Yenana 30 October 2007 TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative • TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Most people live - whether physically or morally – in a very restricted circle of their potential being. We all have reservoirs of life to draw upon of which we do not dream... William James TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Township realities ¾60+% population in townships ¾Unemployment 50+% in townships ¾75+% leakage of local buying power ¾Private sector investment very low ¾Under-performing residential property markets TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative • Something needs to be done! • We must dream bigger! • Have a broader vision! TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Overall NDP Approach • Programme Goals • Evaluation Criteria • Funding Allocation • Round 1, 2, 3 & (4) TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Project Locations Round 1 and 2 TTTTRRII TrainingTypes for Township of Renewal Projects Initiative 1. High Street TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Types of Project 2. Nodal TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative Types of Project 3. Public Transport TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative NDP Unit Project Examples • Njoli • Ngangelizwe • Vilakazi Precinct • Orlando Ekhaya • Monwabisi • Ndwedwe • Bridge City TTTTRRII Training for Township Renewal Initiative NDPG Projects Ref Township -

THE EXPERIENCES of TEENAGE MOTHERS LIVING in KATLEHONG, MOFOKENG SECTION: a RETROSPECTIVE STUDY. a Report on a Study Project

THE EXPERIENCES OF TEENAGE MOTHERS LIVING IN KATLEHONG, MOFOKENG SECTION: A RETROSPECTIVE STUDY. A report on a study project presented to The Department of Social Work School of Human and Community Development Faculty of Humanities University of the Witwatersrand In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Bachelor of Social Work by KHUTSO MALWA 685326 SUPERVISOR: MS LAETITIA PETERSEN DECEMBER, 2016 ii DECLARATION A research project submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of the degree Bachelor of Social Work in the Faculty of Humanities, At the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg December, 2016 I declare that the project is my own, unaided work. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination at this or any other university. All sources have been correctly referenced using the APA format of referencing. -------------------------------- ---------------------------- Khutso Malwa Date Degree Bachelor of Social Work iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS From the bottom of my heart, I would like to thank the following people: Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Ms. Laetitia Petersen for her support, encouragement and patience. Under her guidance I have learnt a great deal about my research study and about myself. I am thankful for her helpful, kind and gentle nature throughout the year. I would like to thank firstly the two teenage mothers who allowed me to interview them for pretesting purposes. Then I would like to thank the nine strong mothers who gave up their time to participate in my study. I wish them all the best with their future aspirations, with their families and children. I hope that they will continue being good mothers and not give up on their dreams. -

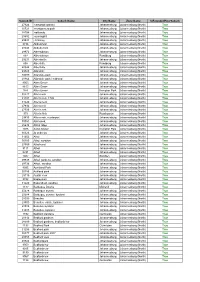

Netflorist Designated Area List.Pdf

Subrub ID Suburb Name City Name Zone Name IsExtendedHourSuburb 27924 carswald kyalami Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30721 montgomery park Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28704 oaklands Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28982 sunninghill Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29534 • bramley Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 8736 Abbotsford Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28048 Abbotts ford Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29972 Albertskroon Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 897 Albertskroon Randburg Johannesburg (North) True 29231 Albertsville Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 898 Albertville Randburg Johannesburg (North) True 28324 Albertville Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 29828 Allandale Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30099 Allandale park Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28364 Allandale park / midrand Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 9053 Allen Grove Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 8613 Allen Grove Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 974 Allen Grove Kempton Park Johannesburg (North) True 30227 Allen neck Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 31191 Allen’s nek, 1709 Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 31224 Allens neck Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 27934 Allens nek Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 27935 Allen's nek Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 975 Allen's Nek Roodepoort Johannesburg (North) True 29435 Allens nek, rooderport Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 30051 Allensnek, Johannesburg Johannesburg (North) True 28638 -

Katlehong/Vosloorus/Thokoza

2019 1 Some detail What is Roots? Reading the charts A landscape survey which spans The community is identified in the 110 metropolitan communities top right corner of the page across South Africa with a total sample of 27 468. Each The sample size, universe size and community is sampled description are displayed at the independently bottom of the page (e.g. (n) 300, representing 40,000 households Formal households are selected or 60,000 shoppers) using multi-stage cluster sampling and purchase decision makers Community data is compared to (shoppers) are randomly the composite of similar selected from the household for communities interview. see below for details In this document The community’s information is always shown in colour and the A community is a defined comparative Metro data in grey geographical footprint from which the samples are drawn. Where applicable community The map provided defines these data is trended back 10 years or boundaries. as far as comparable Large Metros – 62 Communities Medium Metros –18 Communities Small Metros –30 Communities Johannesburg, Cape Town, Tshwane, Nelson Mandela Bay, Bloemfontein, Western Cape (Garden Route, Wine Lands, Ethikwini/Durban, Ekhruleni Pietermaritzburg, West Rand, Vaal, Kimberley, Helderburg) KZN (North and South Coast, Eg: Sandton, Athlone, Durban North, Boksburg, Polokwane, Buffalo City/East London Zululand, Midlands) Mpumalanga (Mbombela, Witbank, Bethal, Middleburg, Ermelo,Lydenburg) Freestate (Welkom, Bethlehem, Kroonstad) Eastern Cape (Uitenhage, Mthatha), Rustenburg 2 Map -

Understanding Our People a Journey Through Census

UNDERSTANDING OUR PEOPLE: A JOURNEY THROUGH CENSUS 2011 IN GAUTENG Acknowledgements : PRESENTATION BY Dr Ros Hirschowitz RENDANI MABILA AND Sharthi Laldaparsad MARCUS SEEPE Table of content 1. Introduction 2. Geographic Information 3. Demographic Information 4. Migration 5. Education 6. Labour Market 7. Income Status 8. Summary 9. References Introduction Ekurhuleni meaning “place of peace” in Xitsonga is a metropolitan municipality situated at the east part of Gauteng x and share boarders with City of Johannesburg ,Sedibeng, City of Tshwane and Nkangala (Mpumalanga ) The metro covers an area of about 2 000km2 and is highly urbanized with a population density of 1 609 people per km2. City of Ekurhuleni is divided into six planning regions namely: v Region A:Germiston v Region B:Thembisa v Region C:Daveyton v Region D:Benoni v Region E:Boksburg v Region F:Katlehong/Thokoza Region A: Germiston Germiston is a city in the East Rand of Gauteng it is also the location of Rand Airport and home to the South African Airways Museum Region B: Thembisa Tembisa is a large township situated to the north of Kempton Park on the East Rand, It was established in 1957 when Africans were resettled from Alexandra and other areas in Edenvale, Kempton Park, Midrand and Germiston. Region C: Daveyton Daveyton is a township that borders Etwatwa to the north, springs to the east, Benoni to the south, and Boksburg to the West. The nearest town is Benoni, which is 18 kilometres away. Daveyton is one of the largest townships with many population in South Africa, together with Etwatwa,Herry Gwala and Cloverdene.It was established in 1952 when 151,656 people were moved from Benoni, the old location of Etwatwa. -

Heidelberg Main Seat of Lesedi Magisterial District

# # !C # # # ## ^ !C# !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C^ # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C # ^ # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # !C # # !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # #!C # !C # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # ^ # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # ##^ !C # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ## # # # #!C # !C# # # #!C # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # # # # # # # # !C # # #!C # # # # # # !C# ## # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ### !C # # !C # # # # !C # ## ## ## !C # # !C # !. # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # ### # # # # # # # # # # ^ # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # !C !C## # # # ## # !C # # # # # !C# # # # # # # !C # # # # !C # ^ # # # !C # ^ # # ## !C # # # !C #!C ## # # # # # # ## # # # # ## # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # #