Privacy and the Debate Over Same-Sex Marriage Versus Unions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Institutions, Social Change, and Same-Sex Marriage

WAX.DOC 10/5/2005 1:41 PM The Conservative’s Dilemma: Traditional Institutions, Social Change, and Same-Sex Marriage AMY L. WAX* I. INTRODUCTION What is the meaning of marriage? The political fault lines that have emerged in the last election on the question of same-sex marriage suggest that there is no consensus on this issue. This article looks at the meaning of marriage against the backdrop of the same-sex marriage debate. Its focus is on the opposition to same-sex marriage. Drawing on the work of some leading conservative thinkers, it investigates whether a coherent, secular case can be made against the legalization of same-sex marriage and whether that case reflects how opponents of same-sex marriage think about the issue. In examining these questions, the article seeks more broadly to achieve a deeper understanding of the place of marriage in social life and to explore the implications of the recent controversy surrounding its reform. * Professor of Law, University of Pennsylvania Law School. 1059 WAX.DOC 10/5/2005 1:41 PM One striking aspect of the debate over the legal status of gay relationships is the contrast between public opinion, which is sharply divided, and what is written about the issue, which is more one-sided. A prominent legal journalist stated to me recently, with grave certainty, that there exists not a single respectable argument against the legal recognition of gay marriage. The opponents’ position is, in her word, a “nonstarter.” That viewpoint is reflected in discussions of the issue that appear in the academic literature. -

WHY COMPETITION in the POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA a Strategy for Reinvigorating Our Democracy

SEPTEMBER 2017 WHY COMPETITION IN THE POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA A strategy for reinvigorating our democracy Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter ABOUT THE AUTHORS Katherine M. Gehl, a business leader and former CEO with experience in government, began, in the last decade, to participate actively in politics—first in traditional partisan politics. As she deepened her understanding of how politics actually worked—and didn’t work—for the public interest, she realized that even the best candidates and elected officials were severely limited by a dysfunctional system, and that the political system was the single greatest challenge facing our country. She turned her focus to political system reform and innovation and has made this her mission. Michael E. Porter, an expert on competition and strategy in industries and nations, encountered politics in trying to advise governments and advocate sensible and proven reforms. As co-chair of the multiyear, non-partisan U.S. Competitiveness Project at Harvard Business School over the past five years, it became clear to him that the political system was actually the major constraint in America’s inability to restore economic prosperity and address many of the other problems our nation faces. Working with Katherine to understand the root causes of the failure of political competition, and what to do about it, has become an obsession. DISCLOSURE This work was funded by Harvard Business School, including the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness and the Division of Research and Faculty Development. No external funding was received. Katherine and Michael are both involved in supporting the work they advocate in this report. -

Jonathan Rauch

Jonathan Rauch Jonathan Rauch, a contributing editor of National Journal and The Atlantic, is the author of several books and many articles on public policy, culture, and economics. He is also a guest scholar at the Brookings Institution, a leading Washington think-tank. He is winner of the 2005 National Magazine Award for columns and commentary and the 2010 National Headliner Award for magazine columns. His latest book is Gay Marriage: Why It Is Good for Gays, Good for Straights, and Good for America, published in 2004 by Times Books (Henry Holt). It makes the case that same-sex marriage would benefit not only gay people but society and the institution of marriage itself. Although much of his writing has been on public policy, he has also written on topics as widely varied as adultery, agriculture, economics, gay marriage, height discrimination, biological rhythms, number inflation, and animal rights. His multiple-award-winning column, “Social Studies,” was published in National Journal (a Washington-based weekly on government, politics, and public policy) from 1998 to 2010, and his features appeared regularly both there and in The Atlantic. Among the many other publications for which he has written are The New Republic, The Economist, Reason, Harper’s, Fortune, Reader’s Digest, U.S. News & World Report, The New York Times newspaper and magazine, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, The New York Post, Slate, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Public Interest, The Advocate, The Daily, and others. Rauch was born and raised in Phoenix, Arizona, and graduated in 1982 from Yale University. -

Building Better Care: Improving the System for Delivering Health Care to Older Adults and Their Families

Building Better Care: Improving the System for Delivering Health Care To Older Adults and Their Families A Special Forum Hosted by the Campaign for Better Care July 28, 2010 • National Press Club Speaker Biographies DEBRA L. NESS, MS President National Partnership for Women & Families For over two decades, Debra Ness has been an ardent advocate for the principles of fairness and social justice. Drawing on an extensive background in health and public policy, Ness possesses a unique understanding of the issues that women and families face at home, in the workplace, and in the health care arena. Before assuming her current role as President, she served as Executive Vice President of the National Partnership for 13 years. Ness has played a leading role in positioning the organization as a powerful and effective advocate for today’s women and families. Ness serves on the boards of some of the nation’s most influential organizations working to improve health care. She sits on the Boards of the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), the National Quality Forum (NQF), and recently completed serving on the Board of Trustees of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. She co-chairs the Consumer-Purchaser Disclosure Group and sits on the Steering Committee of the AQA and on the Quality Alliance Steering Committee. Ness also serves on the board of the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) and on the Executive Committee of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR), co-chairing LCCR’s Health Task Force. THE HONORABLE SHELDON WHITEHOUSE United States Senator For more than 20 years, Sheldon Whitehouse has served the people of Rhode Island: championing health care reform, standing up for our environment, helping solve fiscal crises, and investigating public corruption. -

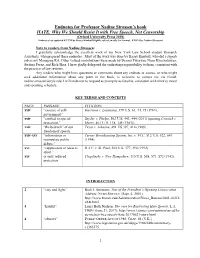

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen's Book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen’s book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship (Oxford University Press 2018) Endnotes last updated 4/27/18 by Kasey Kimball (lightly edited, mostly for format, 4/28/18 by Nadine Strossen) Note to readers from Nadine Strossen: I gratefully acknowledge the excellent work of my New York Law School student Research Assistants, who prepared these endnotes. Most of the work was done by Kasey Kimball, who did a superb job as my Managing RA. Other valued contributions were made by Dennis Futoryan, Nana Khachaturyan, Stefano Perez, and Rick Shea. I have gladly delegated the endnoting responsibility to them, consistent with the practice of law reviews. Any readers who might have questions or comments about any endnote or source, or who might seek additional information about any point in the book, is welcome to contact me via Email: [email protected]. I will endeavor to respond as promptly as feasible, consistent with a heavy travel and speaking schedule. KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS PAGE PASSAGE CITATION xxiv “essence of self- Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64, 74, 75 (1964). government.” xxiv “entitled to special Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 444 (2011) (quoting Connick v. protection.” Myers, 461 U. S. 138, 145 (1983)). xxiv “the bedrock” of our Texas v. Johnson, 491 US 397, 414 (1989). freedom of speech. xxiv-xxv “information or Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. FCC, 512 U.S. 622, 641 manipulate public (1994). debate.” xxv “suppression of ideas is R.A.V. v. St. -

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION a BROOKINGS BRIEFING SAVING DEMOCRACY: a PLAN for REAL REPRESENTATION in AMERICA Washington, D.C. Tues

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION A BROOKINGS BRIEFING SAVING DEMOCRACY: A PLAN FOR REAL REPRESENTATION IN AMERICA Washington, D.C. Tuesday, November 14, 2006 MODERATOR: E.J. DIONNE, JR. Senior Fellow, Governance Studies, The Brookings Institution; Columnist, The Washington Post PANELISTS: JONATHAN RAUCH Guest Scholar, The Brookings Institution; Columnist, National Journal THE HONORABLE EARL BLUMENAUER U.S. Representative (D-Ore.) KEVIN O’LEARY Senior Researcher, The Center for the Study of Democracy University of California, Irvine 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. DIONNE: I should tell you that I come at this book as both a strong friend and a skeptic. As I told Kevin when we talked months ago, I always thought that Oscar Wilde’s criticism of socialism, which was also a criticism of any form of highly participatory democracy, is the problem with socialism is that it would require too many evenings, that is to say too many meetings, and at the gatherings of the politically assiduous, victory often goes not to the wisest nor to the strongest nor to the majority but to the loudest and to those who can sit and sit and sit. Now, Kevin has a variety of solutions to that problem which he will talk about. I just want to share with you what some very thoughtful people have said about his book. That quote, by the way, came from a review I wrote many, many, many years ago of a wonderful book called Beyond Adversary Democracy written by a political scientist named Jane Mansbridge. Jane wrote a perfect blurb for Kevin’s book. -

APA Newsletters

APA Newsletters Volume 04, Number 2 Spring 2005 NEWSLETTER ON PHILOSOPHY AND LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER ISSUES FROM THE EDITOR, CAROL QUINN FROM THE CHAIR, MARY BLOODSWORTH-LUGO CURRENT COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP FEATURED ESSAYS MARY K. BLOODSWORTH-LUGO “Transgender Bodies and the Limits of Body Theory” RICHARD D. MOHR “America’s Promise and the Lesbian and Gay Future: The Concluding Chapter of The Long Arc of Justice” BOOK REVIEWS Richard D. Mohr: The Long Arc of Justice REVIEWED BY JAMES S. STRAMEL Laurence M. Thomas and Michael E. Levin: Sexual Orientation and Human Rights REVIEWED BY RAJA HALWANI © 2005 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN: 1067-9464 APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues Carol Quinn, Editor Spring 2005 Volume 04, Number 2 FROM THE EDITOR FROM THE CHAIR Carol Quinn Mary Bloodsworth-Lugo Washington State University In this issue, we feature two terrific papers, “Transgender My term as chair of the APA Committee on the Status of Bodies and the Limits of Body-Theory” by Mary Bloodsworth- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People in the Lugo, and “America’s Promise and the Lesbian and Gay Future,” Profession began on July 1, 2004. The committee would like which is the concluding chapter of Richard Mohr’s new book to thank Mark Chekola for his service as chair of the committee. The Long Arc of Justice. In her paper, Bloodsworth-Lugo Mark’s term ended on June 30, 2004. discusses transgender bodies as possible limit cases to frameworks offered by feminist theories of sexual difference, During the past year, the LGBT Committee sponsored and she engages the irony that discourses on bodies are often programs at all three APA meetings. -

THOMAS W. MERRILL Department of Government School of Public Affairs American University Washington D.C

THOMAS W. MERRILL Department of Government School of Public Affairs American University Washington D.C. [email protected] Current Positions: Associate Professor of Government, School of Public Affairs, American University, 2015– present Associate Director, Political Theory Institute at American University, 2015–present. Previous Experience: Visiting Fellow, James Madison Program for American Ideals and Institutions, Princeton University, Fall 2017 Interim Chair, Department of Government, School of Public Affairs, American University (2016-17) Assistant Professor, Department of Government, School of Public Affairs, American University, 2009–2015 Forbes Visiting Fellow, James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions, Princeton University, 2011–12 Senior Research Analyst, President’s Council on Bioethics, 2008–2009. Research Analyst, 2007–2008. Research Consultant, 2006–2007 Assistant Professor (Tutor), St. John’s College, Annapolis, 2006–2009 Postdoctoral Fellow, Program on Constitutional Government, Harvard University, 2004–2005 Postdoctoral Fellow, American Enterprise Institute, 2003–2004 Education: Ph.D., Duke University, Department of Political Science, 2003 MA, Duke University, Department of Political Science. Passed Preliminary Exams with Distinction, 1999 BA, University of Chicago, 1996 Administrative Experience: Interim Chair, Department of Government, 2016-17. Oversaw annual budget of $110,000; coordinates scheduling for approximately 100 class sections per semester; handles term and adjunct faculty appointments and reappointments; oversaw reform to cut the number of credits in the Political Science Major Coordinator for the Undergraduate Program in the Department of Government, 2015-16. Led syllabus review each semester; coordinated the first year of the “Conversations with SPA Alumni” speaker series; very engaged with AU’s replacement of its General Education program with the new AUCore. -

Peaceful Coexistence: Reconciling Nondiscrimination Principles with Civil Liberties

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS PEACEFUL COEXISTENCE: RECONCILING NONDISCRIMINATION PRINCIPLES WITH CIVIL LIBERTIES BRIEFING REPORT SEPTEMBER 2016 U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Martin R. Castro, Chairman bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Patricia Timmons-Goodson, Vice Chair directed to: Roberta Achtenberg Gail L. Heriot • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Peter N. Kirsanow being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their David Kladney race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national Karen K. Narasaki origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Mauro A. Morales, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 1331 Pennsylvania Ave NW Suite 1150 • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to Washington, DC 20425 discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or (202) 376-7700 national origin, or in the administration of justice. www.usccr.gov • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

A Survival Guide for a World at Odds

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE HOW TO THINK: A SURVIVAL GUIDE FOR A WORLD AT ODDS INTRODUCTION: RYAN STREETER, AEI DISCUSSION PARTICIPANTS: ALAN JACOBS, BAYLOR UNIVERSITY; AUTHOR, “HOW TO THINK: A SURVIVAL GUIDE FOR A WORLD AT ODDS” JONATHAN RAUCH, BROOKINGS INSTITUTION YUVAL LEVIN, NATIONAL AFFAIRS PETE WEHNER, ETHICS & PUBLIC POLICY CENTER MODERATOR: YUVAL LEVIN, NATIONAL AFFAIRS 10:00–11:15 AM TUESDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2017 EVENT PAGE: http://www.aei.org/events/how-to-think-a-survival-guide-for-a- world-at-odds/ TRANSCRIPT PROVIDED BY DC TRANSCRIPTION – WWW.DCTMR.COM RYAN STREETER: Good morning, everyone. Welcome to the American Enterprise Institute. My name is Ryan Streeter. I’m the director of domestic policy studies here at AEI. And it’s my pleasure to welcome all of you to today’s event, featuring a very distinguished panel and a distinguished author, Dr. Alan Jacobs, from Baylor University here to talk about his new book, “How to Think: A Guide for the Perplexed.” I’m glad you’ve come out and joined us today for this talk. Dr. Jacobs is a distinguished professor of the humanities at Baylor University. He’s the author of a dozen books and many articles. The most recent book before this one was a book on — it’s called the “Common Book of Prayer: A Biography.” He’s ranged across a wide range of topics in his work. And he’s authored “How to Think,” this book, in a very timely way, at a time of fractious and agitated public square and debates that occupy much of our time, much of our energy, much of our mental energy and have made politics exhausting for many. -

Why the Rush to Same-Sex Marriage? and Who Stands to Benefit?

Public Relations: Why the Rush to Same-Sex Marriage? And Who Stands to Benefit? Julie Abraham The Women's Review of Books, Vol. 17, No. 8. (May, 2000), pp. 12-14. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0738-1433%28200005%2917%3A8%3C12%3APRWTRT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-L The Women's Review of Books is currently published by Old City Publishing, Inc.. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ocp.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

Restoring Congress As the First Branch

R STREET POLICY STUDY NO. 50 CONTENTS January 2016 Introduction 1 No longer the first branch 2 Congress lobotomizes itself 3 A Congress without its own knowledge RESTORING CONGRESS AS THE is a dependent Congress 5 Rebuild the machinery 6 FIRST BRANCH Will Ryan’s reforms strengthen the House? 8 Kevin R. Kosar and Various Authors Four steps for reviving the first branch 10 INTRODUCTION 1 Kevin R. Kosar “[a]ll legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a n late 2014, the R Street Institute launched the Gover- Congress of the United States.” These include fundamental nance Project. Its task is large: to assess and improve the powers of governance, such as establishing currency and fix- state of America’s system of national self-governance, ing its value, regulating economic activity among the states with particular attention to Congress. and with other nations, declaring war, taxing the public and I spending those funds. Our national charter also empowers The need for such inquiry should be obvious. Our federal Congress to conduct oversight to ensure our tax dollars are republic is showing signs of dyspepsia, if not outright dys- well-spent and our laws “faithfully executed” by the presi- function. National public-policy issues, such as immigration dent and the bureaucracy. Hence, to remedy the ills of our reform, long have been deadlocked. Various government federal government necessitates improving Congress. agencies – such as the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, the Internal Revenue Service, and the Department of Defense – The R Street Institute’s Governance Project takes an institu- have been in the headlines due to major scandals and man- tional approach to the problem of governance.