Traditional Institutions, Social Change, and Same-Sex Marriage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Job Discrimination and Gay Rights

650 PART FOUR The Organization and the People in It 4. What sort of formal policies, if any, should them, or are they only trying to reduce companies have regarding sexual harass- their legal liability? Is Schultz right that ment and sexual conduct by employees? corporations tend to focus on sexual mis- Should companies discourage dating and conduct while ignoring larger questions of offi ce romances? sex equality? If so, what explains this? 5. Are corporations genuinely concerned about sexual harassment? Is it a moral issue for READING 11.3 Job Discrimination and Gay Rights JOHN CORVINO Asked why, he explains, “Anti-discrimination ordinances are great, but they don’t fi x peo- Many gay, lesbian, and bisexual Americans suf- ple’s ignorance.” Todd characterizes some of fer from job discrimination because of their sex- his fi rm’s partners as “homophobic”—a few ual orientation. After distinguishing between have made gay jokes in his presence—and he two different senses of discrimination, John worries that, were his sexual orientation to Corvino argues that discriminating against a become known, it would affect his workload, person because of a certain characteristic is advancement opportunities, and general com- justifi ed only if that characteristic is job rel- fort level. When colleagues talk about their evant and that sexual orientation, like race or weekend activities, Todd remains vague. When religion, is not directly relevant to most jobs. they suggest fi xing him up with single female Turning then to the contention that discrimina- coworkers, he jokes that “I don’t buy my meat tion against gays is acceptable because homo- and bread from the same aisle”—then quickly sexuality is immoral, Corvino rebuts three changes the subject. -

WHY COMPETITION in the POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA a Strategy for Reinvigorating Our Democracy

SEPTEMBER 2017 WHY COMPETITION IN THE POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA A strategy for reinvigorating our democracy Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter ABOUT THE AUTHORS Katherine M. Gehl, a business leader and former CEO with experience in government, began, in the last decade, to participate actively in politics—first in traditional partisan politics. As she deepened her understanding of how politics actually worked—and didn’t work—for the public interest, she realized that even the best candidates and elected officials were severely limited by a dysfunctional system, and that the political system was the single greatest challenge facing our country. She turned her focus to political system reform and innovation and has made this her mission. Michael E. Porter, an expert on competition and strategy in industries and nations, encountered politics in trying to advise governments and advocate sensible and proven reforms. As co-chair of the multiyear, non-partisan U.S. Competitiveness Project at Harvard Business School over the past five years, it became clear to him that the political system was actually the major constraint in America’s inability to restore economic prosperity and address many of the other problems our nation faces. Working with Katherine to understand the root causes of the failure of political competition, and what to do about it, has become an obsession. DISCLOSURE This work was funded by Harvard Business School, including the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness and the Division of Research and Faculty Development. No external funding was received. Katherine and Michael are both involved in supporting the work they advocate in this report. -

Jonathan Rauch

Jonathan Rauch Jonathan Rauch, a contributing editor of National Journal and The Atlantic, is the author of several books and many articles on public policy, culture, and economics. He is also a guest scholar at the Brookings Institution, a leading Washington think-tank. He is winner of the 2005 National Magazine Award for columns and commentary and the 2010 National Headliner Award for magazine columns. His latest book is Gay Marriage: Why It Is Good for Gays, Good for Straights, and Good for America, published in 2004 by Times Books (Henry Holt). It makes the case that same-sex marriage would benefit not only gay people but society and the institution of marriage itself. Although much of his writing has been on public policy, he has also written on topics as widely varied as adultery, agriculture, economics, gay marriage, height discrimination, biological rhythms, number inflation, and animal rights. His multiple-award-winning column, “Social Studies,” was published in National Journal (a Washington-based weekly on government, politics, and public policy) from 1998 to 2010, and his features appeared regularly both there and in The Atlantic. Among the many other publications for which he has written are The New Republic, The Economist, Reason, Harper’s, Fortune, Reader’s Digest, U.S. News & World Report, The New York Times newspaper and magazine, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, The New York Post, Slate, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Public Interest, The Advocate, The Daily, and others. Rauch was born and raised in Phoenix, Arizona, and graduated in 1982 from Yale University. -

Debating Religious Liberty and Discrimination

Book Reviews Debating Religious Liberty and Discrimination. By John Corvino, Ryan T. Anderson, and Sheriff Girgis. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017, 262 pp., $21.95 Paper. In 2015, the United States Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision, redefined the institution of marriage by ruling that same-sex couples possessed the “right” to marry. At the time, many cultural observers believed that the marriage debate had finally been settled. However, in the two years since the decision, the opposite has proven true. Rather than resolving the twenty-first century’s most hotly debated culture war issue, Obergefell merely expediated the new frontier of the culture wars: the inevitable collision between erotic and religious liberty. In fact, the confrontation between these liberties—the former, championed by LGBT revolutionaries, and the latter, enshrined and protected by the United States Constitution—has been at the center of several high- profile and contentious legal battles across the country over the last two and a half years, particularly in wedding-related professions, as Christian photographers, florists, bakers, and custom service professionals have faced fines, lawsuits, and even jail time for refusing to participate in ceremonies that violate their religious convictions. This ideological conflict was foreseeable. DuringObergefell oral arguments, Donald Verrilli, President Obama’s Solicitor General, conceded that legalizing same-sex marriage would present a challenge to religious liberty. When pressed by Justice Alito on whether Christian colleges would be forced to provide housing to same-sex couples if marriage were redefined Verrilli replied, “It’s certainly going to be an issue. I don’t deny that.” Prophetically, Verrilli’s remark foreshadowed the post-Obergefell political and legal landscape increasingly antagonistic to institutions and professionals guided by sincere religious convictions. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES School of Humanities Hume’s Conception of Character by Robert Heath Mahoney Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2009 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Doctor of Philosophy HUME’S CONCEPTION OF CHARACTER by Robert Heath Mahoney The thesis reconstructs Hume’s conception of character. Character is not just an ethical concern in Hume’s philosophy: Hume emphasises the importance of character in his ethics, aesthetics and history. The reconstruction therefore pays attention to Hume’s usage of the concept of character in his clearly philosophical works, the Treatise of Human Nature and the two Enquiries , as well as his less obviously philosophical works, the Essays, Moral, Political and Literary and the History of England . -

Building Better Care: Improving the System for Delivering Health Care to Older Adults and Their Families

Building Better Care: Improving the System for Delivering Health Care To Older Adults and Their Families A Special Forum Hosted by the Campaign for Better Care July 28, 2010 • National Press Club Speaker Biographies DEBRA L. NESS, MS President National Partnership for Women & Families For over two decades, Debra Ness has been an ardent advocate for the principles of fairness and social justice. Drawing on an extensive background in health and public policy, Ness possesses a unique understanding of the issues that women and families face at home, in the workplace, and in the health care arena. Before assuming her current role as President, she served as Executive Vice President of the National Partnership for 13 years. Ness has played a leading role in positioning the organization as a powerful and effective advocate for today’s women and families. Ness serves on the boards of some of the nation’s most influential organizations working to improve health care. She sits on the Boards of the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), the National Quality Forum (NQF), and recently completed serving on the Board of Trustees of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. She co-chairs the Consumer-Purchaser Disclosure Group and sits on the Steering Committee of the AQA and on the Quality Alliance Steering Committee. Ness also serves on the board of the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) and on the Executive Committee of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR), co-chairing LCCR’s Health Task Force. THE HONORABLE SHELDON WHITEHOUSE United States Senator For more than 20 years, Sheldon Whitehouse has served the people of Rhode Island: championing health care reform, standing up for our environment, helping solve fiscal crises, and investigating public corruption. -

Lee, George, Wax, and Geach on Gay Rights and Same-Sex Marriage Andrew Koppelman Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected]

Northwestern University School of Law Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Working Papers 2010 Careful With That Gun: Lee, George, Wax, and Geach on Gay Rights and Same-Sex Marriage Andrew Koppelman Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected] Repository Citation Koppelman, Andrew, "Careful With That Gun: Lee, George, Wax, and Geach on Gay Rights and Same-Sex Marriage" (2010). Faculty Working Papers. Paper 30. http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/facultyworkingpapers/30 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Draft: Jan. 11, 2010 Careful With That Gun: Lee, George, Wax, and Geach on Gay Rights and Same-Sex Marriage Andrew Koppelman* About half of Americans think that homosexual sex is morally wrong.1 More than half oppose same-sex marriage.2 * John Paul Stevens Professor of Law and Professor of Political Science, Northwestern University. Thanks to Marcia Lehr and Michelle Shaw for research assistance, and to June Carbone, Mary Anne Case, Mary Geach, Martha Nussbaum, and Dorothy Roberts for helpful comments. 1 This number is however shrinking. The Gallup poll found in 1982 that only 34 percent of respondents agreed that “homosexuality should be considered an acceptable alternative lifestyle.” The number increased to 50 percent in 1999 and 57 percent in 2007. Lydia Saad, Americans Evenly Divided on Morality of Homosexuality, June 18, 2008, available at http://www.gallup.com/poll/108115/Americans-Evenly-Divided-Morality- Homosexuality.aspx (visited April 27, 2009). -

Philosophy and Religious Studies

SPRING 2014 Philosophy and Religious Studies LEARN. DO. LIVE. From the Chair - Dr. Matt Altman With the recent groundbreaking of the Science Building (phase two) on campus, we’re once again reminded of how much people love the sciences. The humanities and the arts are often overlooked, like a run-over donut. They shouldn’t be. In philosophy and religious studies in particular, we deal with perennial questions of human existence, and it’s by considering these questions that we live up to our humanity. We step back and ask about right and wrong, knowledge, the mind, the basis of law and government, gender, meaning, the transcendent — all of the topics that have been perplexed us for thousands of years. Some of the world’s great artists have majored in philosophy, including writers such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Elie Wiesel, Umberto Eco, and David Foster Wallace; filmmakers Ethan Coen and Wes Anderson; and many others. The skills that students develop in philosophy and religious studies are also valued in the business world. Every employer looks for people who can think critically, can express themselves clearly verbally and in writing, and can engage people with different viewpoints — and all of these skills are developed especially well in philosophy and religious studies courses. The highest growth in jobs currently is in so-called “interaction-based work” that requires people who are able to communicate well, and in that area, humanities majors have a distinct advan- tage over majors in the sciences and even in business. Many of the most innovative and successful business executives in recent years have had undergraduate philosophy degrees, including activist investor Carl Icahn, former chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Sheila Bair, hedge fund manager George Soros, former Time Warner CEO Gerald Levin, Flickr co-founder Stewart Butterfield, PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel, and many more. -

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues in Philosophy

NEWSLETTER | The American Philosophical Association Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues in Philosophy FALL 2013 VOLUME 13 | NUMBER 1 FROM THE EDITOR William S. Wilkerson ARTICLES John Corvino Same-Sex Marriage and the Definitional Objection Raja Halwani Same-Sex Marriage Anonymous On Family and Family (The Ascension of Saint Connie) Richard Nunan U.S. v. Windsor and Hollingsworth v. Perry Decisions: Supreme Court Conservatives at the Deep End of the Pool VOLUME 13 | NUMBER 1 FALL 2013 © 2013 BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL ASSOCIatION ISSN 2155-9708 APA NEWSLETTER ON Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues in Philosophy WILLIAM S. WILKERSON, EDITOR VOLUME 13 | NUMBER 1 | FALL 2013 FROM THE EDITOR ARTICLES William Wilkerson Same-Sex Marriage and the Definitional UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA IN HUNTSVILLE, [email protected] Objection The two recent Supreme Court decisions regarding same- sex marriage are the occasion of this collection of essays John Corvino discussing the merits and problems of same-sex marriage, WaYNE STATE UNIVERSITY, [email protected] the status of queer families, and the legal ramifications. Excerpted and reprinted by permission from John Corvino The first two essays tackle the question from both more and Maggie Gallagher, Debating Same-Sex Marriage (Oxford abstract and more concrete locations. John Corvino has University Press, 2012). kindly consented to reprint his careful analysis of one the most common objections made to same-sex marriage. According to the Definitional Objection, what we are denying Conversely, Raja Halwani builds upon objections to same- to gays is not marriage, since marriage is by definition the sex marriage put forward by gays and lesbians, like Michael union of a man and a woman. -

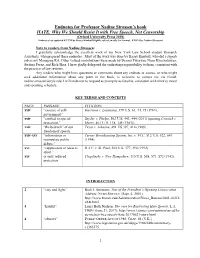

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen's Book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen’s book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship (Oxford University Press 2018) Endnotes last updated 4/27/18 by Kasey Kimball (lightly edited, mostly for format, 4/28/18 by Nadine Strossen) Note to readers from Nadine Strossen: I gratefully acknowledge the excellent work of my New York Law School student Research Assistants, who prepared these endnotes. Most of the work was done by Kasey Kimball, who did a superb job as my Managing RA. Other valued contributions were made by Dennis Futoryan, Nana Khachaturyan, Stefano Perez, and Rick Shea. I have gladly delegated the endnoting responsibility to them, consistent with the practice of law reviews. Any readers who might have questions or comments about any endnote or source, or who might seek additional information about any point in the book, is welcome to contact me via Email: [email protected]. I will endeavor to respond as promptly as feasible, consistent with a heavy travel and speaking schedule. KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS PAGE PASSAGE CITATION xxiv “essence of self- Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64, 74, 75 (1964). government.” xxiv “entitled to special Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 444 (2011) (quoting Connick v. protection.” Myers, 461 U. S. 138, 145 (1983)). xxiv “the bedrock” of our Texas v. Johnson, 491 US 397, 414 (1989). freedom of speech. xxiv-xxv “information or Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. FCC, 512 U.S. 622, 641 manipulate public (1994). debate.” xxv “suppression of ideas is R.A.V. v. St. -

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION a BROOKINGS BRIEFING SAVING DEMOCRACY: a PLAN for REAL REPRESENTATION in AMERICA Washington, D.C. Tues

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION A BROOKINGS BRIEFING SAVING DEMOCRACY: A PLAN FOR REAL REPRESENTATION IN AMERICA Washington, D.C. Tuesday, November 14, 2006 MODERATOR: E.J. DIONNE, JR. Senior Fellow, Governance Studies, The Brookings Institution; Columnist, The Washington Post PANELISTS: JONATHAN RAUCH Guest Scholar, The Brookings Institution; Columnist, National Journal THE HONORABLE EARL BLUMENAUER U.S. Representative (D-Ore.) KEVIN O’LEARY Senior Researcher, The Center for the Study of Democracy University of California, Irvine 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. DIONNE: I should tell you that I come at this book as both a strong friend and a skeptic. As I told Kevin when we talked months ago, I always thought that Oscar Wilde’s criticism of socialism, which was also a criticism of any form of highly participatory democracy, is the problem with socialism is that it would require too many evenings, that is to say too many meetings, and at the gatherings of the politically assiduous, victory often goes not to the wisest nor to the strongest nor to the majority but to the loudest and to those who can sit and sit and sit. Now, Kevin has a variety of solutions to that problem which he will talk about. I just want to share with you what some very thoughtful people have said about his book. That quote, by the way, came from a review I wrote many, many, many years ago of a wonderful book called Beyond Adversary Democracy written by a political scientist named Jane Mansbridge. Jane wrote a perfect blurb for Kevin’s book. -

APA Newsletters

APA Newsletters Volume 04, Number 2 Spring 2005 NEWSLETTER ON PHILOSOPHY AND LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER ISSUES FROM THE EDITOR, CAROL QUINN FROM THE CHAIR, MARY BLOODSWORTH-LUGO CURRENT COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP FEATURED ESSAYS MARY K. BLOODSWORTH-LUGO “Transgender Bodies and the Limits of Body Theory” RICHARD D. MOHR “America’s Promise and the Lesbian and Gay Future: The Concluding Chapter of The Long Arc of Justice” BOOK REVIEWS Richard D. Mohr: The Long Arc of Justice REVIEWED BY JAMES S. STRAMEL Laurence M. Thomas and Michael E. Levin: Sexual Orientation and Human Rights REVIEWED BY RAJA HALWANI © 2005 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN: 1067-9464 APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues Carol Quinn, Editor Spring 2005 Volume 04, Number 2 FROM THE EDITOR FROM THE CHAIR Carol Quinn Mary Bloodsworth-Lugo Washington State University In this issue, we feature two terrific papers, “Transgender My term as chair of the APA Committee on the Status of Bodies and the Limits of Body-Theory” by Mary Bloodsworth- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People in the Lugo, and “America’s Promise and the Lesbian and Gay Future,” Profession began on July 1, 2004. The committee would like which is the concluding chapter of Richard Mohr’s new book to thank Mark Chekola for his service as chair of the committee. The Long Arc of Justice. In her paper, Bloodsworth-Lugo Mark’s term ended on June 30, 2004. discusses transgender bodies as possible limit cases to frameworks offered by feminist theories of sexual difference, During the past year, the LGBT Committee sponsored and she engages the irony that discourses on bodies are often programs at all three APA meetings.