Harmonics: Composing in Extended Just Intonation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

The 17-Tone Puzzle — and the Neo-Medieval Key That Unlocks It

The 17-tone Puzzle — And the Neo-medieval Key That Unlocks It by George Secor A Grave Misunderstanding The 17 division of the octave has to be one of the most misunderstood alternative tuning systems available to the microtonal experimenter. In comparison with divisions such as 19, 22, and 31, it has two major advantages: not only are its fifths better in tune, but it is also more manageable, considering its very reasonable number of tones per octave. A third advantage becomes apparent immediately upon hearing diatonic melodies played in it, one note at a time: 17 is wonderful for melody, outshining both the twelve-tone equal temperament (12-ET) and the Pythagorean tuning in this respect. The most serious problem becomes apparent when we discover that diatonic harmony in this system sounds highly dissonant, considerably more so than is the case with either 12-ET or the Pythagorean tuning, on which we were hoping to improve. Without any further thought, most experimenters thus consign the 17-tone system to the discard pile, confident in the knowledge that there are, after all, much better alternatives available. My own thinking about 17 started in exactly this way. In 1976, having been a microtonal experimenter for thirteen years, I went on record, dismissing 17-ET in only a couple of sentences: The 17-tone equal temperament is of questionable harmonic utility. If you try it, I doubt you’ll stay with it for long.1 Since that time I have become aware of some things which have caused me to change my opinion completely. -

Perceptual Interactions of Pitch and Timbre: an Experimental Study on Pitch-Interval Recognition with Analytical Applications

Perceptual interactions of pitch and timbre: An experimental study on pitch-interval recognition with analytical applications SARAH GATES Music Theory Area Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University Montréal • Quebec • Canada August 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. Copyright © 2015 • Sarah Gates Contents List of Figures v List of Tables vi List of Examples vii Abstract ix Résumé xi Acknowledgements xiii Author Contributions xiv Introduction 1 Pitch, Timbre and their Interaction • Klangfarbenmelodie • Goals of the Current Project 1 Literature Review 7 Pitch-Timbre Interactions • Unanswered Questions • Resulting Goals and Hypotheses • Pitch-Interval Recognition 2 Experimental Investigation 19 2.1 Aims and Hypotheses of Current Experiment 19 2.2 Experiment 1: Timbre Selection on the Basis of Dissimilarity 20 A. Rationale 20 B. Methods 21 Participants • Stimuli • Apparatus • Procedure C. Results 23 2.3 Experiment 2: Interval Identification 26 A. Rationale 26 i B. Method 26 Participants • Stimuli • Apparatus • Procedure • Evaluation of Trials • Speech Errors and Evaluation Method C. Results 37 Accuracy • Response Time D. Discussion 51 2.4 Conclusions and Future Directions 55 3 Theoretical Investigation 58 3.1 Introduction 58 3.2 Auditory Scene Analysis 59 3.3 Carter Duets and Klangfarbenmelodie 62 Esprit Rude/Esprit Doux • Carter and Klangfarbenmelodie: Examples with Timbral Dissimilarity • Conclusions about Carter 3.4 Webern and Klangfarbenmelodie in Quartet op. 22 and Concerto op 24 83 Quartet op. 22 • Klangfarbenmelodie in Webern’s Concerto op. 24, mvt II: Timbre’s effect on Motivic and Formal Boundaries 3.5 Closing Remarks 110 4 Conclusions and Future Directions 112 Appendix 117 A.1,3,5,7,9,11,13 Confusion Matrices for each Timbre Pair A.2,4,6,8,10,12,14 Confusion Matrices by Direction for each Timbre Pair B.1 Response Times for Unisons by Timbre Pair References 122 ii List of Figures Fig. -

Muziek Voor Volwassenen / Johan Derksen Zaterdag 20 Oktober 2018

Muziek voor Volwassenen / Johan Derksen Zaterdag 20 oktober 2018 Album van de Week: "Life Will Humble You"- Malford Milligan & The Southern Aces TITEL ARTIEST COMPONIST TIJD PLATENLABEL LABELNO CD TITEL 09.00 - 10.00 uur 1 Insane asylum Long John Baldry Willie Dixon 5:24 Stoney Plain Records SPCD 1376 The best of Stoney Plain years 2 Walkin' with you baby Luther Guitar Junior Johnson Luther Johnson 4:17 Rounder Europe FAB14 50120 Slide guitar 3 Last train from poor valley Nothin' Fancy Mike Andes 4:59 Mountain Fever Records MFR151010 By any other name 4 One way ticket to Memphis Bobby King & Terry Evans Jorge Calderon 5:02 Rounder Europe FAB14 50120 Slide guitar 5 There's a chance Broken Sun D.G. van Schie, B.M.E. Dietvorst 3:30 Butler Records Promo On 6 Play on little girl Smokin' Joe Kubek Band Walker, Aaron 4:19 Rounder Europe FAB14 50120 Slide guitar 7 I'm glad to do it Malford Milligan & The Southern Aces Homer Banks, Johnny Keyes 4:47 Stagger Lee Records, Royal Family Records RFRCD-2903 Life will humble you 8 Son of the south Mohead John Mohead 4:24 Rogue Records CSCCD 1159 Son of the south 9 Baby please set a date George Thorogood Elmore James, 4:50 Rounder Europe FAB14 50120 Slide guitar 10 Making memories of us Rodney Crowell Rodney Crowell 4:12 RC1 Records 854083000478 Acoustic classics 11 Wild about you baby Mike Morgan and the Crawl Elmore James 4:29 Rounder Europe FAB14 50120 Slide guitar 12 Backstroke Ronnie Earl Albert Collins 3:47 Stoney Plain Records SPCD 1347 Spread the love 10.00 - 11.00 uur 1 Bring it on home to me Octopus F. -

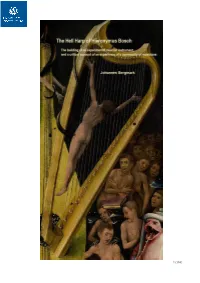

The Hell Harp of Hieronymus Bosch. the Building of an Experimental Musical Instrument, and a Critical Account of an Experience of a Community of Musicians

1 (114) Independent Project (Degree Project), 30 higher education credits Master of Fine Arts in Music, with specialization in Improvisation Performance Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring 2019 Author: Johannes Bergmark Title: The Hell Harp of Hieronymus Bosch. The building of an experimental musical instrument, and a critical account of an experience of a community of musicians. Supervisors: Professor Anders Jormin, Professor Per Anders Nilsson Examiner: Senior Lecturer Joel Eriksson ABSTRACT Taking a detail from Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden Of Earthly Delights as a point of departure, an instrument is built for a musical performance act deeply involving the body of the musician. The process from idea to performance is recorded and described as a compositional and improvisational process. Experimental musical instrument (EMI) building is discussed from its mythological and sociological significance, and from autoethnographical case studies of processes of invention. The writer’s experience of 30 years in the free improvisation and new music community, and some basic concepts: EMIs, EMI maker, musician, composition, improvisation, music and instrument, are analyzed and criticized, in the community as well as in the writer’s own work. The writings of Christopher Small and surrealist ideas are main inspirations for the methods applied. Keywords: Experimental musical instruments, improvised music, Hieronymus Bosch, musical performance art, music sociology, surrealism Front cover: Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly -

Imaginary Marching Band Paper 2

The Imaginary Marching Band: An Experiment in Invisible Musical Interfaces Scott Peterman Parsons, The New School for Design 389 6th Avenue #3 New York, NY 10014 USA +1 917 952 2360 [email protected] www.imaginarymarchingband.com ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION The Imaginary Marching Band is a series of open- The Imaginary Marching Band is not just an source wearable instruments that allow the wearer to experiment in interaction design or music generation. create real music simply by pantomiming playing an This is a project geared towards a larger goal: the instrument. liberation of spontaneous creativity from the theater, Keywords studio, and writing desk and to embed it into our daily lives. MIDI Interface, Wearable Computer, Fashionable Technology, Digital Music, Invisible It is also a performance piece, an actual band who will Instruments be performing at a variety of festivals and institutions around the world this summer and fall. This project is open-source, both as software and as hardware. The hope is to encourage others to experiment within this area of design: the creation of invisible interfaces that mimic real world actions, and in so doing inspire a sense of play and enhance - rather than diminish - the creative experience. INSPIRATION But almost none of these instruments have brought the The twentieth century saw frequent bursts of Dionysian joy of actually creating music to a wider innovation in the manufacture and design of musical audience, nor the act of performance out into the “real” instruments. From early novelties by Russolo and world; if anything, these inventions appeal exclusively Theramin to mid-century instrument modification by to the most experimental of musical spaces. -

Newly Cataloged Items in the Music Library August - December 2017

Newly Cataloged Items in the Music Library August - December 2017 Call Number Author Title Publisher Enum Publication Date MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.1 Vivaldi, Antonio, 1678- Vivaldi : Venetian splendour. International Masters 2006 2006 1741. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.2 Bach, Johann Sebastian, Bach : Baroque masterpieces. International Masters 2005 2005 1685-1750. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.3 Bach, Johann Sebastian, Bach : master musician. International Masters 2007 2007 1685-1750. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 B37 v.5 Handel, George Frideric, Handel : from opera to oratorio. International Masters 2006 2006 1685-1759. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.1 Haydn, Joseph, 1732- Haydn : musical craftsman. International Masters 2006 2006 1809. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.2 Haydn, Joseph, 1732- Haydn : master of music. International Masters 2006 2006 1809. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.3 Mozart, Wolfgang Mozart : musical masterpieces. International Masters 2005 2005 Amadeus, 1756-1791. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.4 Mozart, Wolfgang Mozart : classic melodies. International Masters 2005 2005 Amadeus, 1756-1791. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 C63 v.5 Mozart, Wolfgang Mozart : magic of music. International Masters 2007 2007 Amadeus, 1756-1791. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 .1 Beethoven, Ludwig van, Beethoven : the spirit of freedom. International Masters 2005 2005 1770-1827. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 Rossini, Gioacchino, Rossini : opera and overtures. International Masters 2006 v.10 2006 1792-1868. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 Schumann, Robert, 1810- Schumann : poetry and romance. International Masters 2006 v.11 2006 1856. Pub., MUSIC. MCD3.C63 E17 Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Mendelssohn : dreams and fantasies. International Masters 2005 v.12 2005 Felix, 1809-1847. -

Andrián Pertout

Andrián Pertout Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition Volume 1 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Produced on acid-free paper Faculty of Music The University of Melbourne March, 2007 Abstract Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition encompasses the work undertaken by Lou Harrison (widely regarded as one of America’s most influential and original composers) with regards to just intonation, and tuning and scale systems from around the globe – also taking into account the influential work of Alain Daniélou (Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales), Harry Partch (Genesis of a Music), and Ben Johnston (Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource). The essence of the project being to reveal the compositional applications of a selection of Persian, Indonesian, and Japanese musical scales utilized in three very distinct systems: theory versus performance practice and the ‘Scale of Fifths’, or cyclic division of the octave; the equally-tempered division of the octave; and the ‘Scale of Proportions’, or harmonic division of the octave championed by Harrison, among others – outlining their theoretical and aesthetic rationale, as well as their historical foundations. The project begins with the creation of three new microtonal works tailored to address some of the compositional issues of each system, and ending with an articulated exposition; obtained via the investigation of written sources, disclosure -

<I>Manifestations</I>: a Fixed Media Microtonal Octet

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2017 Manifestations: A fixed media microtonal octet Sky Dering Van Duuren University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Van Duuren, Sky Dering, "Manifestations: A fixed media microtonal octet. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4908 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Sky Dering Van Duuren entitled "Manifestations: A fixed media microtonal octet." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Andrew L. Sigler, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Barbara Murphy, Jorge Variego Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Manifestations A fixed media microtonal octet A Thesis Presented for the Master of Music Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Skylar Dering van Duuren August 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Skylar van Duuren. -

Xii - Les Tempéraments Justes De Plus De 12 Divisions (19, 31, 43)

XII - LES TEMPÉRAMENTS JUSTES DE PLUS DE 12 DIVISIONS (19, 31, 43) 1. INTRODUCTION Les acousticiens et théoriciens de la musique ont toujours été affrontés au problème de l’Intonation Juste. Depuis Ramis (ou Ramos) en 1482 [34], jusqu’à Helmholtz en 1863 [8], ils ont essayé de concevoir des échelles à intervalles consonants. Ça a repris en Europe dès le début du XXe siècle pour continuer outre- atlantique jusqu’à nos jours. Plusieurs fois on a eu recours à des octaves de plus de 12 divisions, ce qui donne des intervalles inférieurs au demi-ton, on parle alors de micro-tons. Continuons de parler de Ton dans le sens le plus large, ou bien d’Unité. Le système de F. Salinas (1557) était composé de 19 degrés et était censé être juste [48]. Défendu par Woolhouse au XIXe siècle, il sera relancé au XXe siècle par J. Yasser [49]. Le système à 31 tons a aussi des origines anciennes, l’archicembalo conçu en 1555 par Vicentino avait déjà 31 touches 1. Il avait pour objectif, entre autres, d’introduire des quarts de ton pour interpréter les madrigaux du napolitain Gesualdo. Etudié par le physicien C. Huygens à l’aide d’arguments scientifiques, il est basé sur la présence de la quinte, de la tierce et de la septième justes. 1 Comme dans tous les domaines, la Renaissance a connu une grande effervescence en théorie musicale. On a ressorti les anciens manuscrits (Aristoxène, Euclide, Nicomaque, Ptolemé,…), mais aussi hélas ceux de Boèce, unique référence du haut Moyen Âge. Le système de Vicentino n’avait donc rien d’insolite. -

Analyzing Modular Smoothness in Video Game Music

Analyzing Modular Smoothness in Video Game Music Elizabeth Medina-Gray KEYWORDS: video game music, modular music, smoothness, probability, The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, Portal 2 ABSTRACT: This article provides a detailed method for analyzing smoothness in the seams between musical modules in video games. Video game music is comprised of distinct modules that are triggered during gameplay to yield the real-time soundtracks that accompany players’ diverse experiences with a given game. Smoothness —a quality in which two convergent musical modules fit well together—as well as the opposite quality, disjunction, are integral products of modularity, and each quality can significantly contribute to a game. This article first highlights some modular music structures that are common in video games, and outlines the importance of smoothness and disjunction in video game music. Drawing from sources in the music theory, music perception, and video game music literature (including both scholarship and practical composition guides), this article then introduces a method for analyzing smoothness at modular seams through a particular focus on the musical aspects of meter, timbre, pitch, volume, and abruptness. The method allows for a comprehensive examination of smoothness in both sequential and simultaneous situations, and it includes a probabilistic approach so that an analyst can treat all of the many possible seams that might arise from a single modular system. Select analytical examples from The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker and Portal -

Divisions of the Tetrachord Are Potentially Infinite in Number

EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION ''''HEN I WAS A young student in California, Lou Harrison suggested that I send one of my first pieces, Piano Study #5 (forJPR) to a Dr. Chalmers, who might publish it in his journal Xenbarmonikon. Flattered and fascinated, I did, and John did, and thus began what is now my twenty year friendship with this polyglot fungus researcher tuning guru science fiction devotee and general everything expert. Lou first showed me the box of papers, already called Divisions ofthe Tetracbord, in 1975. I liked the idea of this grand, obsessive project, and felt that it needed to be availablein a way that was, likeJohn himself, out of the ordinary. When Jody Diamond, Alexis Alrich, and I founded Frog Peak Music (A Composers' Collective) in the early 80S, Divisions (along with Tenney's then unpublished Meta + Hodos) was in my mind as one of the publishing collective's main reasons for existing, and for calling itself a publisher of"speculative theory." The publication of this book has been a long and arduous process. Re vised manuscripts traveled with me from California to Java and Sumatra (John requested we bring him a sample of the local fungi), and finally to our new home in New Hampshire. The process of writing, editing, and pub lishing it has taken nearly fifteen years, and spanned various writing tech nologies. (When John first started using a word processor, and for the first time his many correspondents could actually read his long complicated letters, my wife and I were a bit sad-we had enjoyed reading his com pletely illegible writing aloud as a kind of sound poetry).