Angelica Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essential Oil Proudly South African & Foreign Formulations Presented by Professor Aubrey Parsons 2019

Essential oil Proudly South African & Foreign Formulations Presented by Professor Aubrey Parsons 2019 Photo by Itineranttrader / Public domain • Angelica (Angelica archangelica) • Aniseed (Illicium Verum) • Basil (Ocimum basilicum) • Bay (Pimenta racemose) • Benzoin resinoid (Styrax benzoin) • Bergamot (Citrus bergamia) Essential Oils • Black Pepper (Piper nigrum) • Cajuput (Melaleuca cajiputi) • Camphor (Cinnamomum camphora) • Cardamom (Eletarria cardamomum) • Carraway (Carum carvi) • Carrot Seed (Daucus carota • Cedarwood Atlas (Cedrus atlantica) • Chamomile Blue Egyptian (Matricaria recutita) • Chamomile Wild Maroc (Ormensis multicaulis) • Chamomile Roman (Anthemis nobilis) • Cinnamon (Cinnamon zaylanicum) • Citronella (Cymbopogon nardus) • Clary Sage (Salvia sclarea) Essential Oils • Clove Leaf (Eugenia caryophyllata) • Coriander (Coriandrum sativum) • Cummin (Cuminum cyminum) • Cypress (Cupressa sempervirens) • Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus) • Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) • Frankincense Olibanum (Boswellia thurifera) • Garlic (Allium sativum) • Geranium (Pelargonium graveolens) • Ginger (Zingiber officinale) • Grapefruit (Citrus paradise) • Ho Leaf (Cinnamomum camphora • Hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis) Essential Oils • Jasmine Absolute (Jasmine officinalis) • Juniper (Juniperus communis) • Lavender (Lavandula angustifolium) • Lemon (Citrus limonum) • Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) • Lime (Citrus aurrantifolia) • Mandarin (Citrus reticulata bianco) • Marjoram Cultivated (Marjorama hortensis) • Myrrh (Commiphora Myrrha) • Neroli (Citrus -

Xanthomonas Campestris Pv. Coriandri on Coriander

Identification of a X anthom onas pathogen of coriander from O regon A.R. Poplawsky (1), L. Robles (1), W . Chun (1), M .L. DERIE (2), L.J . du T oit (2), X.Q . M eng (3), and R.L. Gilbertson (3). (1) University of Idaho, M oscow ID; (2) W ashington State University, M ount V ernon W A; (3) University of California, Davis CA. A B S TR A CT Table 2. Umbelliferous host range of US coriander seed strains of X. campestris and Phytopathology 94:S 85. Poster 248, A PS A nn. M tg, 31 J uly–4 A ugust 2004, A naheim , CA . carrot seed strains of X. campestris pv. carotae A coriander seed lot grown in O regon yielded Xanthomonas-like colonies on M D5A agar, at 4.6 x 10 5 CFU/g S train of X . S ym ptom s of infection 25 days > inoculation (# plants sym ptom atic/# inoculated) seed. Colonies were mucoid, convex and yellow on Y DC agar. Koch’s postulates were completed on coriander. cam pestris W ater-soaked lesions developed on inoculated coriander leaves and turned necrotic in 1-2 weeks, with the Carrot Celery Coriander D ill Fennel Lovage Parsley Parsnip growing point killed on some plants. T he bacterium also was pathogenic on fennel, lovage and parsnip; but not on US coriander seed strains 1st test (M ay 2003) dill, celery or parsley. O n carrot, isolates occasionally produced very mild symptoms 3-4 weeks after inoculation. US-A + (1/9) - + (6/6) - + (12/12) + (6/8) - - T he bacteria were motile, Gram-negative, aerobic rods, positive for production of amylase, catalase, US-B - - + (6/6) - + (8/8) + (3/7) - + (1/18) xanthomonadins and H2S from cysteine, but negative for quinate metabolism, oxidase and nitrate reductase. -

Proposal for Plot Based Plant Phenology Sampling in Puale Bay, Alaska (Adapted from Long Term Ecological Monitoring Program, Vegetation Sampling Protocols 2006)

Plant Phenology Puale Bay 2010 Proposal for Plot Based Plant Phenology Sampling in Puale Bay, Alaska (Adapted from Long Term Ecological Monitoring Program, Vegetation Sampling Protocols 2006) Stacey E. Pecen U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alaska Peninsula/Becharof NWR, P.O. Box 277, King Salmon, AK 99613 BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES Phenology, the timing of major biological events during a plant or animal’s life, can be monitored to detect changes in climate. Major events are called phenophases: leaf emergence, flowering, fruit ripening, and senescing. According to Menzel and Estrella (2001), plant phenology studies have shown that the average growing season is increasing by 0.2 days/year. It is especially important to monitor changes in higher latitudes, such as Alaska, where global warming is expected to occur earlier and at a greater magnitude (Henry and Molau 1997). The Northern Hemisphere (above 40o N) has experienced an increase in temperature of at least 0.5oC/decade from 1966-1995 (Serreze et al. 2000, Euskirchen et al. 2009). Monitoring species abundance and diversity is also vital. Environmental conditions dictate the composition of plant communities. Changes can occur over time, disrupting the balance of these interactions. In a nine year study at Toolik Lake, AK, Chapin et al. (1995) found that species richness declined 30-50% when the mean temperature was increased by 3.5˚C. Forbs and grasses decreased in abundance while woody species, such as Betula spp., increased. Changes in species abundance in regions of the arctic, as a result of warming, were also noted by Euskirchen et al. (2009). -

Ornithocoprophilous Plants of Mount Desert Rock, a Remote Bird-Nesting Island in the Gulf of Maine, U.S.A

RHODORA, Vol. 111, No. 948, pp. 417–447, 2009 E Copyright 2009 by the New England Botanical Club ORNITHOCOPROPHILOUS PLANTS OF MOUNT DESERT ROCK, A REMOTE BIRD-NESTING ISLAND IN THE GULF OF MAINE, U.S.A. NISHANTA RAJAKARUNA Department of Biological Sciences, San Jose´ State University, One Washington Square, San Jose´, CA 95192-0100 e-mail: [email protected] NATHANIEL POPE AND JOSE PEREZ-OROZCO College of the Atlantic, 105 Eden Street, Bar Harbor, ME 04609 TANNER B. HARRIS University of Massachusetts, Fernald Hall, 270 Stockbridge Road, Amherst, MA 01003 ABSTRACT. Plants growing on seabird-nesting islands are uniquely adapted to deal with guano-derived soils high in N and P. Such ornithocoprophilous plants found in isolated, oceanic settings provide useful models for ecological and evolutionary investigations. The current study explored the plants foundon Mount Desert Rock (MDR), a small seabird-nesting, oceanic island 44 km south of Mount Desert Island (MDI), Hancock County, Maine, U.S.A. Twenty-seven species of vascular plants from ten families were recorded. Analyses of guano- derived soils from the rhizosphere of the three most abundant species from bird- 2 nesting sites of MDR showed significantly higher (P , 0.05) NO3 , available P, extractable Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn, and significantly lower Mn compared to soils from the rhizosphere of conspecifics on non-bird nesting coastal bluffs from nearby MDI. Bio-available Pb was several-fold higher in guano soils than for background levels for Maine. Leaf tissue elemental analyses from conspecifics on and off guano soils showed significant differences with respect to N, Ca, K, Mg, Fe, Mn, Zn, and Pb, although trends were not always consistent. -

Major Lineages Within Apiaceae Subfamily Apioideae: a Comparison of Chloroplast Restriction Site and Dna Sequence Data1

American Journal of Botany 86(7): 1014±1026. 1999. MAJOR LINEAGES WITHIN APIACEAE SUBFAMILY APIOIDEAE: A COMPARISON OF CHLOROPLAST RESTRICTION SITE AND DNA SEQUENCE DATA1 GREGORY M. PLUNKETT2 AND STEPHEN R. DOWNIE Department of Plant Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801 Traditional sources of taxonomic characters in the large and taxonomically complex subfamily Apioideae (Apiaceae) have been confounding and no classi®cation system of the subfamily has been widely accepted. A restriction site analysis of the chloroplast genome from 78 representatives of Apioideae and related groups provided a data matrix of 990 variable characters (750 of which were potentially parsimony-informative). A comparison of these data to that of three recent DNA sequencing studies of Apioideae (based on ITS, rpoCl intron, and matK sequences) shows that the restriction site analysis provides 2.6± 3.6 times more variable characters for a comparable group of taxa. Moreover, levels of divergence appear to be well suited to studies at the subfamilial and tribal levels of Apiaceae. Cladistic and phenetic analyses of the restriction site data yielded trees that are visually congruent to those derived from the other recent molecular studies. On the basis of these comparisons, six lineages and one paraphyletic grade are provisionally recognized as informal groups. These groups can serve as the starting point for future, more intensive studies of the subfamily. Key words: Apiaceae; Apioideae; chloroplast genome; restriction site analysis; Umbelliferae. Apioideae are the largest and best-known subfamily of tem, and biochemical characters exhibit similarly con- Apiaceae (5 Umbelliferae) and include many familiar ed- founding parallelisms (e.g., Bell, 1971; Harborne, 1971; ible plants (e.g., carrot, parsnips, parsley, celery, fennel, Nielsen, 1971). -

Food Recommendations Lovage Perennial Edible Herb Originally

Herbs-Who Are You?/ Written by Tome Shaaltiel, presented by Joan Plisko Herb ID pointers Medicinal value Fun fact! Food recommendations Lovage Perennial Some people Likely In foods and edible herb take lovage by unsafe to beverages, lovage originally from mouth as consume is used for Mediterranean "irrigation during flavoring. region, In the therapy" for pain pregnancy. carrot family, and swelling leaves look (inflammation) of like celery, the lower urinary grows up to tract, for 6ft tall, foliage preventing of is in an kidney stones, umbrella form and to increase with yellow the flow of urine flowers, roots during urinary are greyish tract infections. pink. But there is no good scientific research to support the use of lovage for these or other conditions. The oil can cause irritation to skin in a pure form. Thyme Perennial, essential oils in Can help Lemon thyme is woody stems thyme are you’re your great in a lemon with tiny green packed with anti- snoring cur or lemon pie. leaves on septic, anti-viral, problems! French or Italian opposite sides anti-rheumatic, Thyme is great in of the stem, anti-parasitic and quiches and purple or anti- lasagna. white flower fungal properties, depends on great immune the variety, system booster. grow in a The oil can cause bush. irritation to skin in a pure form. Comfrey Perennial, big If chewing it up Comfrey has Don't eat please! furry leaves, with your teeth deep roots that can stick or with a grinder that reach to clothes, all into a paste or the aquifer grow from one wrapping the bringing stem, purple leaves around energy and flowers, not fractures, water from edible. -

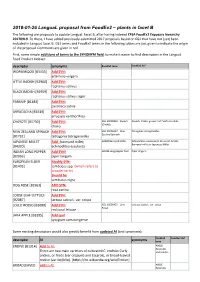

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

Harvesting Herbs

222 N Havana Spokane WA 99202 (509) 477-2181 e-mail: [email protected] http://extension.wsu.edu/spokane/master-gardener-program/home-lawn-and-garden/ C159 HARVESTING HERBS Herb plants (the ‘h’ is pronounced in England, generally silent in America) are flowering plants whose above-ground stems do not become woody. The plants commonly referred to as ‘herbs’ are valued for their medicinal, decorative properties, culinary flavors, and aromatic scents. When you look at the entire spectrum of herbs available, different parts of individual plants - leaves, flowers, seeds and roots – can be used for different purposes: Plant leaves or foliage are commonly used for flavoring food. Many seeds have highly individual flavors. Some stems are important for flavoring. Flowers tend to be used for dyes and perfumes. Roots are used as vegetables or as medicinal constituents. Sometimes the entire plant is used. Parts of an herb plant, other than the leaves, that are used for food flavoring are called ‘spices.’ Harvest time for herbs is decided by the individual plant. Most aromatic herbs are ready just as buds open into full blossom. The plants then contain the most volatile oils, which provide the greatest amount of fragrance and flavor. There are exceptions to this rule. Sage leaves should be picked when buds first appear. Hyssop, lavender and thyme should be picked when in full bloom. Many herbs are ready to flower and therefore harvest in mid-summer. Throughout the growing season, pick healthy leaves (not those yellow or brown with age) to use whole or chopped in culinary dishes. -

Poisonous Hemlocks

POISONOUS HEMLOCKS THEIR IDENTIFICATION AND CONTROL J . M. Tucker • M. E. Fowle r • W. A. Harvey • L. J. Berry .. POISONOUS HEMLOCKS THEIR IDENTIFI CA TION AND CONTROL THE poisonous plants referred to in this publica tion as "hemlocks" are members of the carrot or parsley family, Umbelliferae, and should not be confused with true hemlocks, which are coniferous trees of the pine family, Pinaceae. Poisonous hem locks are of two genera: Conium (Poison Hemlock), and Cicuta {Water Hemlock). They have a general family resemblance to one another but are not closely related; their toxic properties and effects are different, they present different problems to the live stock industry, and they have different diagnostic features. THE AUTHORS: J.M. Tucker is Professor of Botany and Botanist in the Experiment Station, Davis; M. E. Fowler is Assistant Professor of Veterinary Medicine and Assistant Veterinarian in the Experiment Station, Davis; W. A. Harvey is Extension Weed Control Specialist, Agri cultural Extension Service, Davis; L. J. Berry is Range Manage ment Specialist, Agricultural Extension Service, University ol California, Davis. OCTOBER, 1964 --------WARNING-------- 2,4-D is classified as an injurious material, by the State Department of Agriculture, and before it can be purchased or used a permit must be obtained from the County Agricultural, Commissioner. It should be used with care and at a time and in such a manner that it will not drift to other plants or properties and cause injury to susceptible plants or result in an illegal residue on other food or feed crops. THE GROWER IS RESPONSIBLE for residues on his own crops as well as for problems caused by drift of a chemical from his property to other properties or crops. -

BWSR Featured Plant Name: Purple-Stemmed Angelica

BOARD OF WATER rn, AND SOIL RESOURCES 2018 December Plant of the Month BWSR Featured Plant Name: Purple-stemmed Angelica (Angelica atropurpurea) Plant family: Carrot (Apiaceae) Purple-stemmed A striking 6 to 9 feet tall, purple- Angelica grows in stemmed Angelica is one of moist conditions in full sun to part Minnesota’s tallest wildflowers. This shade, reaching as robust herbaceous perennial grows tall as 9 feet. along streambanks, shores, marshes, Photo Credit: calcareous fens, springs and sedge Karin Jokela, Xerces Society meadows — often in calcium-rich alkaline soils. The species epithet “atropurpurea” comes from the Latin words āter (“dark”) Plant Stats and purpūreus (“purple”), in reference to the deep purple color of the stem. WETLANDSTATEWIDE Flowers bloom from May to July. Like INDICATOR other plants in the carrot family, the STATUS: OBL flowers provide easy-to-access floral PLANTING resources for a wide diversity of flies, METHODS: bees and other pollinators. Although Bare-root, not confirmed for this species, the containers, nectar of other members of the Angelica seed genus can have an intoxicating effect on insects. Both butterflies and bumble bees are reported to lose flight ability, or fly clumsily, for a short period after consuming the nectar. Purple-stemmed Angelica is a host plant for the Eastern black swallowtail butterflyPapilio ( polyxenes asterius) and the umbellifera borer moth (Papaipema birdi). Uses Native American cultures. The consumption must be done projects. Restorationists plant also has many culinary with EXTREME CAUTION. appreciate its ability to Purple-stemmed Angelica uses: the flavorful stems are The similar water hemlock tolerate wet soils, part shade has a long history of human similar in texture to celery and poison hemlock are both and high weed pressure use. -

Herbs Such As Spearmint

171 Greenhouse Road Middleburg, PA 17842 Phone: 570-837-0432 www.englesgreenhouse.com Fax 570-837-2165 BASIL (Ocimum) African Blue Tasty in the kitchen, beautiful in the border. Purple shading radiates from base of leaf to green (Kasar) tip. A dwarf Greek bush Basil with true basil taste. Its attractive, naturally mounded shape and Aristotle amazing fragrance make it a perfect basil for containers, both indoors and out. Water as needed all season to keep soil evenly moist, keeping your eye out for the first sign of Cardinal wilt. Wilting is a sure sign that your basil needs water. Feed with a vegetable fertilizer to ensure your bountiful harvest Cinnamon Basil is unique among basils as it leaves contain noticeable amounts of cinnamate, Cinnamon the same compound which gives cinnamon its distinctive smell. Dolce Fresca Large, sweet leaves ideal for pesto. Plants remain attractive after harvest. This 24-30” columnar basil is well-branched with short internodes creating beautiful towering Everleaf Emerald plants in ground or in pots. Flowering up to 12 weeks later than other basils, it has huge harvest Towers potential over a longer period of time. Dark green, glossy foliage with a traditional Genovese flavor. New dwarf variety of Genovese type basil with large, medium green leaves. A very fragrant plant Genovese Emily with a tight branching habit and long shelf life. Use fresh in pesto and tomato sauces or dry for year round flavor. Holy (Sacred) Red A common ingredient in Thai cuisine and in teas. Used medicinally for digestion and immune Green system support. -

INDEX for 2011 HERBALPEDIA Abelmoschus Moschatus—Ambrette Seed Abies Alba—Fir, Silver Abies Balsamea—Fir, Balsam Abies

INDEX FOR 2011 HERBALPEDIA Acer palmatum—Maple, Japanese Acer pensylvanicum- Moosewood Acer rubrum—Maple, Red Abelmoschus moschatus—Ambrette seed Acer saccharinum—Maple, Silver Abies alba—Fir, Silver Acer spicatum—Maple, Mountain Abies balsamea—Fir, Balsam Acer tataricum—Maple, Tatarian Abies cephalonica—Fir, Greek Achillea ageratum—Yarrow, Sweet Abies fraseri—Fir, Fraser Achillea coarctata—Yarrow, Yellow Abies magnifica—Fir, California Red Achillea millefolium--Yarrow Abies mariana – Spruce, Black Achillea erba-rotta moschata—Yarrow, Musk Abies religiosa—Fir, Sacred Achillea moschata—Yarrow, Musk Abies sachalinensis—Fir, Japanese Achillea ptarmica - Sneezewort Abies spectabilis—Fir, Himalayan Achyranthes aspera—Devil’s Horsewhip Abronia fragrans – Sand Verbena Achyranthes bidentata-- Huai Niu Xi Abronia latifolia –Sand Verbena, Yellow Achyrocline satureoides--Macela Abrus precatorius--Jequirity Acinos alpinus – Calamint, Mountain Abutilon indicum----Mallow, Indian Acinos arvensis – Basil Thyme Abutilon trisulcatum- Mallow, Anglestem Aconitum carmichaeli—Monkshood, Azure Indian Aconitum delphinifolium—Monkshood, Acacia aneura--Mulga Larkspur Leaf Acacia arabica—Acacia Bark Aconitum falconeri—Aconite, Indian Acacia armata –Kangaroo Thorn Aconitum heterophyllum—Indian Atees Acacia catechu—Black Catechu Aconitum napellus—Aconite Acacia caven –Roman Cassie Aconitum uncinatum - Monkshood Acacia cornigera--Cockspur Aconitum vulparia - Wolfsbane Acacia dealbata--Mimosa Acorus americanus--Calamus Acacia decurrens—Acacia Bark Acorus calamus--Calamus