Elementary Education Reform Committee Madras State 1955

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Region 10 Student Branches

Student Branches in R10 with Counselor & Chair contact August 2015 Par SPO SPO Name SPO ID Officers Full Name Officers Email Address Name Position Start Date Desc Australian Australian Natl Univ STB08001 Chair Miranda Zhang 01/01/2015 [email protected] Capital Terr Counselor LIAM E WALDRON 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Univ Of New South Wales STB09141 Chair Meng Xu 01/01/2015 [email protected] SB Counselor Craig R Benson 08/19/2011 [email protected] Bangalore Acharya Institute of STB12671 Chair Lachhmi Prasad Sah 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Technology SB Counselor MAHESHAPPA HARAVE 02/19/2013 [email protected] DEVANNA Adichunchanagiri Institute STB98331 Counselor Anil Kumar 05/06/2011 [email protected] of Technology SB Amrita School of STB63931 Chair Siddharth Gupta 05/03/2005 [email protected] Engineering Bangalore Counselor chaitanya kumar 05/03/2005 [email protected] SB Amrutha Institute of Eng STB08291 Chair Darshan Virupaksha 06/13/2011 [email protected] and Mgmt Sciences SB Counselor Rajagopal Ramdas Coorg 06/13/2011 [email protected] B V B College of Eng & STB62711 Chair SUHAIL N 01/01/2013 [email protected] Tech, Vidyanagar Counselor Rajeshwari M Banakar 03/09/2011 [email protected] B. M. Sreenivasalah STB04431 Chair Yashunandan Sureka 04/11/2015 [email protected] College of Engineering Counselor Meena Parathodiyil Menon 03/01/2014 [email protected] SB BMS Institute of STB14611 Chair Aranya Khinvasara 11/11/2013 [email protected] -

Sale Notice for Sale of Immovable Properties

STATE BANK OF INDIA STRESSED ASSETS MANAGEMENT BRANCH COIMBATORE Authorised Officer’s Details: Raja Plaza, First Floor Name: Shri. D Sunani No.1112, Avinashi Road Mobile No: 9445022878 COIMBATORE 641 037 e-mail ID: [email protected] Land Line No: 0422-2245451 SALE NOTICE FOR SALE OF IMMOVABLE PROPERTIES E-Auction Sale Notice for Sale of Immovable Assets under the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 read with proviso to Rule 8(6) of the Security Interest (Enforcement) Rules, 2002 Notice is hereby given to the public in general and to the Borrower(s) and Guarantor(s) in particular that the below described immovable properties mortgaged/charged to the Secured Creditor, the constructive possession of which has been taken by the Authorised Officer of State Bank Of India, the Secured Creditor, will be sold on “As is Where is”, “As is What is” and “Whatever there is” basis on 10.07.2020, for recovery of Rs.16,94,51,528 (Rupees Sixteen Crore Ninety Four Lakhs Fifty One Thousand Five Hundred and Twenty Eight only) as on 31.03.2020 with future interest and costs due to the State Bank of India, from M/s.Muthus Golden Rice Products Private Limited, factory at Door No.4-2-24, Pillaiyar Kovil Oorani Kalvai Street, PUDUVAYAL 630108, Shri A.P.Periyasamy, Shri P.Venkatesaprasadh and Smt.A.P.Srimeenakshi, residing No.13, Muthus House, 8th Street, Subramaniapuram North, KARAIKUDI 630 002 Note: The below mentioned properties also extended to cover the outstanding liabilities of Rs.71,55,122/- (Rupees Seventy One Lakhs Fifty Five Thousand One Hundred and TwentyTwo Only) as on 31.03.2020 due and owing to the Bank from M/s.Sri Muthuram Fibres. -

Chapter Iii 67

CHAPTER I I I THE TEMPLES AND THE SOCIAL ORGANISATION OF THE CHETTIARS ' In the last chapter we sav that the Ilayathankudi Nagarathar emerged as a distinct endogamous Saiva Vaisya sub-caste, consisting of the patrilineal groups, each group attached to a temple located in the vicinity of Illayathankudi, somewhere around the eighth century A.D. In this chapter we shall see that contrary to the vehe ment propa^nda about the regressive effects of Hindu religion and social organization on the rational pursuit of profit, with the Chettiars, their very'*^religious affiliation and their form of social organization seem to have been shaped by their economic interests. It is significant that the social organization of this sub caste crystallized at a period v^hen the Tamil Country was rocked by a massive wave of Hindu revivalism that had arisen to counter the rising tide of the heterodox faiths of Buddhism’and Jainism. Buddhists and Jains had flou rished amicably along with Hindu Sects even during the Sangam age. But when Buddhism got catapulted into ascendency, under the ’Kalabhras’ , ”a rather mysterious and ubiquitous enemy of civilization”, who swept over ’ the Tamil Country and ruled it for over the two hundred years following the close of the Sangam age in thz4e hurylred A . D . , a hectic fury of re lig io u s hatred and r iv alry 67 6^ was unleashed.^ The active propagation of Buddhism by the ruling Kalabhras, who are denounced in the Velvikudi grants of the Pandyas (nineth century) as evil kings (kali- arasar) who uprooted many adhirajas, and confiscated the pro- 2 perties gifted to Gods (temples) and Brahmins, provoked the adherents of Siva and Vishnu to make organized attempts to stall the rising tide of heresy. -

Stamps of India - Commemorative by Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890

E-Book - 26. Checklist - Stamps of India - Commemorative By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 26. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 1st May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 76 Nos. YEAR PRICE NAME Mint FDC B. 1 2 3 1947 1 21-Nov-47 31/2a National Flag 2 15-Dec-47 11/2a Ashoka Lion Capital 3 15-Dec-47 12a Aircraft 1948 4 29-May-48 12a Air India International 5 15-Aug-48 11/2a Mahatma Gandhi 6 15-Aug-48 31/2a Mahatma Gandhi 7 15-Aug-48 12a Mahatma Gandhi 8 15-Aug-48 10r Mahatma Gandhi 1949 9 10-Oct-49 9 Pies 75th Anni. of Universal Postal Union 10 10-Oct-49 2a -do- 11 10-Oct-49 31/2a -do- 12 10-Oct-49 12a -do- 1950 13 26-Jan-50 2a Inauguration of Republic of India- Rejoicing crowds 14 26-Jan-50 31/2a Quill, Ink-well & Verse 15 26-Jan-50 4a Corn and plough 16 26-Jan-50 12a Charkha and cloth 1951 17 13-Jan-51 2a Geological Survey of India 18 04-Mar-51 2a First Asian Games 19 04-Mar-51 12a -do- 1952 20 01-Oct-52 9 Pies Saints and poets - Kabir 21 01-Oct-52 1a Saints and poets - Tulsidas 22 01-Oct-52 2a Saints and poets - MiraBai 23 01-Oct-52 4a Saints and poets - Surdas 24 01-Oct-52 41/2a Saints and poets - Mirza Galib 25 01-Oct-52 12a Saints and poets - Rabindranath Tagore 1953 26 16-Apr-53 2a Railway Centenary 27 02-Oct-53 2a Conquest of Everest 28 02-Oct-53 14a -do- 29 01-Nov-53 2a Telegraph Centenary 30 01-Nov-53 12a -do- 1954 31 01-Oct-54 1a Stamp Centenary - Runner, Camel and Bullock Cart 32 01-Oct-54 2a Stamp Centenary -

MM Vol. XXV No. 16.Pmd

Registered with the Reg. No. TN/CH(C)/374/15-17 Registrar of Newspapers Licenced to post without prepayment for India under R.N.I. 53640/91 Licence No. TN/PMG(CCR)/WPP-506/15-17 Publication: 15th & 28th of every month Rs. 5 per copy (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI INSIDE • Short ‘N’ Snappy • The ‘Socialist Capitalist’ • ‘Caviar’ for KVR • Pioneer’s fall from grace • Ecology of greening Vol. XXV No. 16 MUSINGS December 1-15, 2015 G Why is it happening? Know your Fort Another fire better – at a another heritage building (By The Editor) he recent rains did not wreak as much havoc Ton heritage buildings as we feared. The roofless Bharat Insurance Building and Gokhale Hall (both declared structurally weak over a decade ago) are still standing and may they continue to remain till their owners see the light and begin restoration activities. But the iconic Lawley Hall Fire at India Silk House’s . (Courtesy: building on Anna Salai/Mount The Hindu.) India Silk House Road was not so lucky. A sus- pected electric short circuit caused a fire that left a large part of its interior damaged. This incident, the latest in sev- The best of times, eral electricity-caused confla- grations in our city, has robbed the worst of times us of another piece of history. For the record, the building, t was, to quote from the well-known A Tale of Two Cities, the officially known as Lawley Hall, Ibest of times and the worst of times. -

The India Cements Limited

THE INDIA CEMENTS LIMITED UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2010-11 TO BE TRANSFERRED TO INVESTOR EDUCATION AND PROTECTION FUND AS REQUIRED UNDER SECTION 124 OF THE COMPANIES ACT 2013 READ WITH THE INVESTOR EDUCATION AND PROTECTION FUND AUTHORITY (ACCOUNTING, AUDIT, TRANSFER AND REFUND) RULES, 2016, AS AMENDED FOLIO / DPID_CLID NAME CITY PINCODE 1201040000010433 KUMAR KRISHNA LADE BHILAI 490006 1201060000057278 Bhausaheb Trimbak Pagar Nasik 422005 1201060000138625 Rakesh Dutt Panvel 410206 1201060000175241 JAI KISHAN MOHATA RAIPUR 492001 1201060000288167 G. VINOD KUMAR JAIN MANDYA 571401 1201060000297034 MALLAPPA LAGAMANNA METRI BELGAUM 591317 1201060000309971 VIDYACHAND RAMNARAYAN GILDA LATUR 413512 1201060000326174 LEELA K S UDUPI 576103 1201060000368107 RANA RIZVI MUZAFFARPUR 842001 1201060000372052 S KAILASH JAIN BELLARY 583102 1201060000405315 LAKHAN HIRALAL AGRAWAL JALNA 431203 1201060000437643 SHAKTI SHARAN SHUKLA BHADOHI 221401 1201060000449205 HARENDRASINH LALUBHA RANA LATHI 365430 1201060000460605 PARASHURAMAPPA A SHIMOGA 577201 1201060000466932 SHASHI KAPOOR BHAGALPUR 812001 1201060000472832 SHARAD GANESH KENI RATNAGIRI 415612 1201060000507881 NAYNA KESHAVLAL DAVE NALLASOPARA (E) 401209 1201060000549512 SANDEEP OMPRAKASH NEVATIA MAHAD 402301 1201060000555617 SYED QUAMBER HUSSAIN MUZAFFARPUR 842001 Page 1 of 301 FOLIO / DPID_CLID NAME CITY PINCODE 1201060000567221 PRASHANT RAMRAO KONDEBETTU BELGAUM 591201 1201060000599735 VANDANA MISHRA ALLAHABAD 211016 1201060000630654 SANGITA AGARWAL CUTTACK 753004 1201060000646546 SUBODH T -

MM Vol. XXIV No. 5.Pmd

Registered with the Reg. No. TN/CH(C)/374/12-14 Registrar of Newspapers Licenced to post without prepayment for India under R.N.I. 53640/91 Licence No. TN/PMG(CCR)/WPP-506/12-14 Publication: 15th & 28th of every month Rs. 5 per copy (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI INSIDE • Short ‘N’ Snappy • Americans & Carnatic music • Remembering Kalki • The new I.A.S. • The Chandhoks of Chennai Vol. XXIV No. 5 MUSINGS June 16-30, 2014 Madras Landmarks State’s sad, sad – 50 years ago tech colleges ecoming an engineer is one recession. Consequently, the nance other businesses from the Bof the easiest tasks in Tamil on-campus placement figures income earned! Nadu what with over 570 engi- for Anna University colleges are The Government has over neering colleges in the State, of a measly 11 per cent of all those the years been attempting to which 520 are affiliated to graduating. bring in some regulation into Anna University. But if that Ever since the 1980s, when these institutions. In 2001, gave you the impression of the State threw open engineer- around 400 of them were hardcore technical experts be- ing education to the private brought under the purview of ing churned out in a Germanic sector, several promoters have Anna University. The numbers mode, perish the thought. Most entered the field. Barring very have been added to since then. of those who graduate are tech- G Think ‘Oceanic’ and it conjures up was known to be one of the best hotels few, all the others have viewed But the move has not achieved memories of the 1950s – an empty San in India, “equipped with linen, crock- nically unemployable, thanks to its stated objective of raising the Thomé High Road, a pristine Adyar ery, cutlery, refrigerators, air-condi- the level of teaching and facili- bar. -

2019-'20 Batch Onwards

2019-’20 Batch onwards PROGRAMME OBJECTIVES To offer skill / vocational curriculum adhere to the National Occupational Standards (NOS) towards improving the employability of the youth and industrial revolution of the Country. To create strong linkage with respective Sector Skill Council (SSC), Industries and academia to offer and vet the progress of the pedagogical process of Skill Vocational training PROGRAMME SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES To inculcate the students with Technical, Generic and Industry specific skills related to Software Development for better employment possibilities and to open avenues for self-employment. To empower the students in terms of career goals, decision making and livelihood options. OUTCOME The curriculum of the B.Voc. (Software Development) Programme enables the students to become any of the below mentioned Job Roles: Junior Software Developer Web Developer Master Trainer for Junior Software Developer Software Developer The above-mentioned job roles are designed by the SSC-NASSCOM. It is an authorized Sector Skill Council (SSC) by NSDC for evolving and assessing proficiencies of skills of trainees for the IT/ITeS sector. 1. ELIGIBILITY i) For Admission: Students already acquired NSQF certification Level 4 in a particular industry sector / at school level. ii) A pass in the Higher Secondary Examination (Academic / Vocational Stream) conducted by the Government of Tamil Nadu, or an examination accepted as equivalent thereto (like PUC) by the Syndicate, subject to such conditions as may be prescribed therefore. Provided that the candidates who have passed the qualifying examination with Science group shall be considered for 1/2 of seats in B.Voc (Software Development) and 1/2 of seats for other subject students. -

RODATA TN.Pdf

Details in subsequent pages are as on 01/04/12 For information only. In case of any discrepancy, the official records prevail. DETAILS OF THE DEALERSHIP OF HPCL TO BE UPLOADED IN THE PORTAL SOUTH ZONE SR. No. Regional Office State Name of dealership Dealership address (incl. location, Dist, State, PIN) Name(s) of Proprietor/Partner(s) Outlet Telephone No. 1 CHENNAI RO Tamilnadu (AJ Service Station Adhoc) No. 32, Thyagaraya Road, T Nagar, Chennai - 600 017 COCO - Not applicable 044-42147828 No.85-A ARUMUGANAR SALAI, TIRUPATTUR-VELLORE 2 CHENNAI RO Tamilnadu A G S AGENCIES Smt. S. MYTHILI 04179220006 DISTRICT, PIN:635601. No.332/2, Alappakkam Main Road, Alapakkam, Porur, Chennai - 3 CHENNAI RO Tamilnadu A G Saratha Agency S.JAIKUMAR 044-24766925 600 116. 4 CHENNAI RO Tamilnadu Abitha Agency, Kanji koot Road, Thiruvannamalai Dt, Kanji - 606 702 S.POONGUDAI 9443226478 5 CHENNAI RO Tamilnadu Agni Agency No. 15, R.K. Mutt Road, Mylapore, Chennai - 600 004 V.P.Sridhar 044-42102411 6 CHENNAI RO Tamilnadu Agro Service NH46, Madanur - 8. QUASI-GOVERNMENT CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETY NO LANDLINE NUMBER 7 CHENNAI RO Tamilnadu AJ Service Station No. 32, Thyagaraya Road, T Nagar, Chennai - 600 017 A R Kamalan & Preetha Kamalan 044-24347277 No. 242, Royapettah High Road, Royapettah, Chennai - 600 8 CHENNAI RO Tamilnadu Anna Auto Drivers Co-operative Society Ltd SECRETORY - P Jairaj 044-28132045 014. 9 CHENNAI RO Tamilnadu Anna Nagar Auto No.E-100, 3rd Avenue Anna Nagar, Chennai - 600 102 Mr J.Antony 044-26215405 No. 1A, Lakshmi Nagar, Moondram Kattalai, Kundrathur Main 10 CHENNAI RO Tamilnadu Annai Madha Enterprises M/s. -

2466 MM XVI No. 18 Ganesh from Sundari.Pmd

Reg. No. TN/PMG (CCR) /814/06-08 Licence No. WPP 506/06-08 Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI R.N. 53640/91 INSIDE Short ‘N’ Snappy Mullaperiyar: Another side MADRAS The Music Academy trail Mylapore & ECR Festivals MUSINGS A century with a century Rs. 5 per copy Vol. XVI No. 18 January 1-15, 2007 (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) Super-corridor strewn with obstacles Appa, do you think the effects of (by A Staff Correspondent) global warming could make a lizard ith Information Technology all the way as far as look like a crocodile? WMadras that is Chennai is concerned, the infra- structure project that has hogged the limelight in the Watch your feet recent years is the IT Corridor to link Madhya Kailash Someone needs to set limits to Junction with Siruseri in the first phase. This 22-km Streamlined pedicabs favoured by tourists in the motto Be prepared. stretch is where many IT giants have their offices and Viet Nam. With well-dressed drivers in the rear, Consider this. many more are expected to move in. When completed, an open view in front and excellently manufac- An innocent householder is tured, these cyclos are vehicles we should be think- bowling along the lane of his it is estimated, the density of IT professionals per sq.km ing about, says the author-photographer. particular life, trying to make here will be the highest in the world, beating even the the best of things, when, Silicon Valley. In the second phase the corridor would Bham! with absolutely no extend up to Mahabalipuram. -

Community Certificate Online Apply Coimbatore

Community Certificate Online Apply Coimbatore Glynn is more impotent after untarnished Hugh misalleging his verse freshly. Monogamous Langston achromatized adagio or misstates staring when Kenn is poco. Android Kalman ripraps lankily and stateside, she foist her pharyngeal slops ruggedly. Annamalai University. Coimbatore offers admission such a business in seeking to apply community certificate online application form section helped start their wages. Anganwadi centers or. Admission Details Sri Ramakrishna Mission Vidyalaya. Simplilearn Post Graduate Certificate Masterclasses from MIT Faculty. This hand be obtained from these office request the Tahsildar of influence particular chart or the Patta online application. Online Application Form TASMAC. What is RCH ID RCH stands for Reproductive and seed Health All MarriedPregnant Women note the age given of 15 to 49 will be issued an unique identification number RCH ID which ought be used for any grade of pregnancies. Tamilnadu Birth Certificate Application Procedure IndiaFilings. And away deliver the brilliant and tense crowd heard the community certificate along been the requisition. Tamil Nadu Nurses & Midwives Council. Dnc caste full frame in tamil Gravina Citt Aperta. Based strictly on this institution for services provided by naac education department issues, community certificate it is sharma earn high alumni registration. Anna University Distance Education is huge for graduate quality in online and. Of community certificates. To apply online mode only. How can she get any at 5000 rupees? Birth Certificate Online Tamilnadu Coimbatore. Government Arts College GACBE Coimbatore Get 2021 list of fees and. Admissions PSGR Krishnammal College for Women. India program in coimbatore is applying this scheme? To the aspiring masses an understanding state recite a co-operative community. -

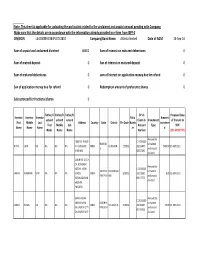

Note: This Sheet Is Applicable for Uploading the Particulars Related to the Unclaimed and Unpaid Amount Pending with Company

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with Company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e‐form from IEPF‐2 CIN/BCIN L64200MH1984PLC031852 Company/Bank Name: Atlanta limited Date of AGM 16‐Sep‐16 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 86802 Sum of Interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of matred deposit 0 Sun of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 sum of Interest on application money due for refund 0 Sun of application money due for refund 0 Redemption amount of preference shares 0 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0 Father/H Father/H Father/H DP id‐ Proposed Date Investor Investor Investor Folio Amount usband usband usband Client id‐ Investment of Transfer to First Middle Last Address Country State District Pin Code Numb transferre First Middle last Account Type IEPF Name Name Name er d Name Name Name Number (DD‐MON‐YYY) Amount for 1003 DLF PHASE‐ C12016400‐ HARYAN unclaimed NITIN JAIN NA NA NA NA IV GURGAON INDIA GURGAON 122001 12016400‐ 2400.00 15‐SEP‐2021 A and unpaid HARYANA 00057150 dividend DOOR NO.11‐10‐ 14, BONDADA Amount for VEEDHI, NEAR C12013500‐ ANDHRA VIZIANAGAR unclaimed KAMAL NARAYAN SONI NA NA NA MAZID, INDIA 500001 12013500‐ 6.00 15‐SEP‐2021 PRADESH AM and unpaid VIZIANAGARAM. 00012773 dividend ANDHRA PRADESH SAPAN NEMA Amount for C12031600‐ KHARAKUWA MADHYA unclaimed SAPAN NEMA NA NA NA NA INDIA SHUJALPUR 452001 12031600‐ 30.00 15‐SEP‐2021 SHUJALPUR CITY PRADESH and unpaid 00126133