Chapter Iii 67

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thirumayam Whether for Polling Location and Name of Building in All Voters Or Sl.No Station Polling Areas Which Polling Station Located Men Only Or No

AC181 - Thirumayam Whether for Polling Location and name of building in All Voters or Sl.No station Polling Areas which Polling Station located Men only or No. Women only 1 2 3 4 5 1 1 Panchayat Union Middle School 1.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-1 oliyamangalam , 2.Oliyamangalam (R.V), All Voters Tiled Building, West Portion Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-1 Eluvankurai , 3.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-2 ,Oliamangalam - 621308 Kayampatti , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS 2 2 Panchayat Union Middle School 1.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-2 Kurunthadipatti , 2.Oliyamangalam (R.V), All Voters Tiled Building, East Portion Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-5 Servaikaranpatti , 3.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-5 ,Oliamangalam - 621308 Vengampatti , 4.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-5 Vettukadu , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS 3 3 Panchayat Union Middle School 1.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-3 Surakkaipatti , 2.Oliyamangalam (R.V), All Voters West Portion Tiled Building Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-3 Sundampatti , 3.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-3 ,Oliamangalam, 621308 Madathupatti , 4.Oliyamangalam (R.V), Oliyamangalam (P) Ward-4 Vellalapatti , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS 4 4 Panchayat Union Elementary 1.Vellayakoundampatti (R.V)Usilampatti (P) Ward-4 Vellayakoundampatti , 2.Avampatti (R.V), All Voters School, Terraced Building, Usilampatti (P) Ward-4 Avampatti , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS OVERSEAS ELECTORS ,Avampatti 622002 5 5 Panchayat Union Elementary -

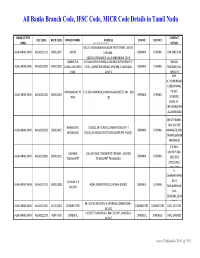

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

Nagarathar Matrimonial Services

Nagarathar Matrimonial Services https://www.indiamart.com/nagarathar-matrimonial-services/ n the earlier days in the Nagarathar community there were well informed elders in our native place who suggested suitable match for the boy or girl. All the marriage or religious functions are attended to by the eligible grooms and brides within ... About Us n the earlier days in the Nagarathar community there were well informed elders in our native place who suggested suitable match for the boy or girl. All the marriage or religious functions are attended to by the eligible grooms and brides within whom suitable alliances were matched. Now a days the, as the community is spread allover the globe, on their employment or occupation, the boy and girls are not able to find time/ interested to go to their native to attend the functions. Hence a place was required to make a link for those who seek alliance for their sons and daughters. A thoughtful Nagarathar Mr. M. Chidambaram Chettiar (Ex Indian Bank Officer) of Devakottai, felt the need of the hour and started the Nagarathar Thirumana Sevai Maiyam at Besant Nagar, Chennai in his own house. He was the forerunner in establishing such a service. After running the service for more than a decade he has decided to hand over the responsibility of continuing the service to a service minded person with a similar aspiration in the year 2001. He has rightly chosen Mr. SM. Lakshmanen of Devakottai who was also a retired Officer of Indian Bank, to succeed him in running the service from Jan. -

Kanadukathan) Address No

கானா翁கா鏍தா இரணி埍ககாவில் ꯁள்ளிகள் Sl. Permanent Address Present Residence Telephone Email Name No. (Kanadukathan) Address No. ID Sri. CT. Muthuraman No. 76. PL. M. CT. House. Ph: 04595-2S3014 KM. Street, 1 Kanadukathan – 630 103. Sivagangai Dist. Sri. CT. Palaniappan No. 76. PL. M. CT. House. Ph: 04595-2S3014 KM. Street, 2 Kanadukathan – 630 103. Sivagangai Dist. Sri. CT. Annamalai No. 14/8, T. KR. Street, Prajwal Vaigai Flats, Ph: 044-24794026 amalaichidambaram@gma il. Kanadukathan – 630 103. N0. 7/318-D, 2nd Main Road, Cell: 9444941149 com 3 Sivagangai Dist. Natesa Nagar, Virugambakkam, Cell : 9677207358 Chennai – 600 092. Sri. M. Chidambaram Flat No 1, Majestic Park, Ph: 044-23764992 48/9/1, Muthukumarappa Cell: 9445378472 4 Road, Saligramam, Chennai – 600 093. Sri. PL. Chidambaram Sree Sathiamurthy lllam, Ph: 04565-226237 No. 1580, Cell: 9442200046 Valluvar Nagar Main Street, 5 Sekkalai Kottai, Karaikudi – 630 002. Sri. A. Chidambaram No. 267/3, 2nd Main Road, Ph: 044-24793079 [email protected] Natesa Nagar, Virugambakkam, Cell : 9444058718 Chennai – 600 092. Cell: 9677048718 6 Smt. CT. Umayal: 9444625960 Selvi. CT. Valliammai: 9600012927 Sri. A. Senthilnathan Arunachalam, New GRT, Ph: 044-24797598 No. 254, 2nd Main Road, Cell: 9843228644 Natesa Nagar, Virugambakkam, Cell: 9486887310 7 Chennai – 600 092. Smt. S. Meenal: 9443037235 Sri. A. Selvakumar 54/18, Manali New Town, Cell: 9841342000 Chennai – 600 103. Cell: 9842108800 8 Cell: 9443140223 Sri. A. Lakshmanan 1570, SE Tradition Trace, Ph: (772)283-2057 [email protected] 34997 Stuart, Cell: 561-310-9681 9 Florida – USA. Cell: 561-801-2310 Zip code: 34997. -

District Census Handbook

Census of India 2011 TAMIL NADU PART XII-B SERIES-34 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SIVAGANGA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS TAMIL NADU CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 TAMIL NADU SERIES-34 PART XII - B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SIVAGANGA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations TAMIL NADU MOTIF SIVAGANGA PALACE Sivaganga palace in Sivaganga Town was built near the Teppakulam has its historical importance. It is a beautiful palace, once the residence of the Zamindar of Sivaganga. The palace was occupied by the ex-rulers, one of the biggest and oldest, wherein Chinna Marudhu Pandiyar gave asylum to Veerapandiya Katta Bomman of Panchalankurichi when the British was trying to hang him as he was fighting against the colonial rule. There i s a temple for Sri Raja Rajeswari, inside the palace. CONTENTS Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 5 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 7 5 Brief History of the District 9 6 Administrative Setup 10 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 11 8 Important Statistics 12 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 16 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 21 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 35 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 55 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 63 (vi) Rural PCA-C.D. blocks wise Village Primary Census Abstract 71 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 163 Tables based on Households Amenities and Assets (Rural 10 Section –II /Urban) at District and Sub-District level. -

Region 10 Student Branches

Student Branches in R10 with Counselor & Chair contact August 2015 Par SPO SPO Name SPO ID Officers Full Name Officers Email Address Name Position Start Date Desc Australian Australian Natl Univ STB08001 Chair Miranda Zhang 01/01/2015 [email protected] Capital Terr Counselor LIAM E WALDRON 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Univ Of New South Wales STB09141 Chair Meng Xu 01/01/2015 [email protected] SB Counselor Craig R Benson 08/19/2011 [email protected] Bangalore Acharya Institute of STB12671 Chair Lachhmi Prasad Sah 02/19/2013 [email protected] Section Technology SB Counselor MAHESHAPPA HARAVE 02/19/2013 [email protected] DEVANNA Adichunchanagiri Institute STB98331 Counselor Anil Kumar 05/06/2011 [email protected] of Technology SB Amrita School of STB63931 Chair Siddharth Gupta 05/03/2005 [email protected] Engineering Bangalore Counselor chaitanya kumar 05/03/2005 [email protected] SB Amrutha Institute of Eng STB08291 Chair Darshan Virupaksha 06/13/2011 [email protected] and Mgmt Sciences SB Counselor Rajagopal Ramdas Coorg 06/13/2011 [email protected] B V B College of Eng & STB62711 Chair SUHAIL N 01/01/2013 [email protected] Tech, Vidyanagar Counselor Rajeshwari M Banakar 03/09/2011 [email protected] B. M. Sreenivasalah STB04431 Chair Yashunandan Sureka 04/11/2015 [email protected] College of Engineering Counselor Meena Parathodiyil Menon 03/01/2014 [email protected] SB BMS Institute of STB14611 Chair Aranya Khinvasara 11/11/2013 [email protected] -

Sale Notice for Sale of Immovable Properties

STATE BANK OF INDIA STRESSED ASSETS MANAGEMENT BRANCH COIMBATORE Authorised Officer’s Details: Raja Plaza, First Floor Name: Shri. D Sunani No.1112, Avinashi Road Mobile No: 9445022878 COIMBATORE 641 037 e-mail ID: [email protected] Land Line No: 0422-2245451 SALE NOTICE FOR SALE OF IMMOVABLE PROPERTIES E-Auction Sale Notice for Sale of Immovable Assets under the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 read with proviso to Rule 8(6) of the Security Interest (Enforcement) Rules, 2002 Notice is hereby given to the public in general and to the Borrower(s) and Guarantor(s) in particular that the below described immovable properties mortgaged/charged to the Secured Creditor, the constructive possession of which has been taken by the Authorised Officer of State Bank Of India, the Secured Creditor, will be sold on “As is Where is”, “As is What is” and “Whatever there is” basis on 10.07.2020, for recovery of Rs.16,94,51,528 (Rupees Sixteen Crore Ninety Four Lakhs Fifty One Thousand Five Hundred and Twenty Eight only) as on 31.03.2020 with future interest and costs due to the State Bank of India, from M/s.Muthus Golden Rice Products Private Limited, factory at Door No.4-2-24, Pillaiyar Kovil Oorani Kalvai Street, PUDUVAYAL 630108, Shri A.P.Periyasamy, Shri P.Venkatesaprasadh and Smt.A.P.Srimeenakshi, residing No.13, Muthus House, 8th Street, Subramaniapuram North, KARAIKUDI 630 002 Note: The below mentioned properties also extended to cover the outstanding liabilities of Rs.71,55,122/- (Rupees Seventy One Lakhs Fifty Five Thousand One Hundred and TwentyTwo Only) as on 31.03.2020 due and owing to the Bank from M/s.Sri Muthuram Fibres. -

A Brief History of Karaikudi

A Brief History of Karaikudi Karaikudi is a greater municipality in Sivaganga district in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu . It is the 20th largest urban agglomeration of Tamil Nadu based on 2011 census data. It is part of the area commonly referred to as " Chettinad " and has been declared a heritage town by the Government of Tamil Nadu ,[1] on account of the palatial houses built with limestone called karai veedu . Karaikudi comes under the Karaikudi assembly constituency, which elects a member to the Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly once every five years, and it is a part of the Sivaganga (Lok Sabha constituency) , which elects its member of parliament (MP) once in five years. The town is administered by the special grade Karaikudi municipality, which covers an area of 33.75 km 2 (13.03 sq mi). As of 2011, the town had a population of 106,714. Roadways are the major mode of transportation to Karaikudi and the nearest airports are Tiruchirapalli International Airport (TRZ) located (95 kilometres (59 mi)) and Madurai International Airport (IXM) is 97 km away from the town History The town derives its name from thorny plant Karai referred in ancient literature as Karaikudi , which in modern times became Karaikudi . The town was established in the 19th century, and the oldest known structure is the Koppudaiya Nayagi Amman Temple.[2] Mahatma Gandhi delivered two speeches in Karaikudi in 1927 and Bharathiyar visited Karaikudi in 1919 to participate in a function.Post independence, the town registered significant growth in the industrial sector. Karaikudi and surrounding areas are generally referred as "Chettinad".The town is home to Nagarathar , a business community and Chettiars , financiers and trade facilitators. -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Tiruppattur Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 Jothika S SenthilKumar (F) 13-1-13, Pethatchi chettiar street, Kottaiyur, , 2 16/11/2020 PAVITHRA SIVARAJAN (H) 1-4-12B, KALIYAMMAN KOVIL, ALAGAPURI, , 3 16/11/2020 sebasthi clinton savarimuthu (F) 2/54, thalakkavur, karaikudi, , 4 16/11/2020 Azhagar Chinnappan (F) 8-23, Asari Theru, Ooranikarai, A.Kalappur, , 5 16/11/2020 Sarasu Azhagar (H) 8/23, Asari Theru, Ooranikarai, A.Kalappur, , 6 16/11/2020 sathishkumar periyandhavar balamani balamani, kilasevalpatti, periyandhavar (F) kilasevalpatti, , 7 16/11/2020 Swathi pillai daughter in law pillai (O) Rajamani Ammal Illam, manachai ,Thrichy main road, manachai village, , 8 16/11/2020 Shanmugi Shanmugi Periyannan Periyannan (F) 8, chithambaram ambalam theru, kottaiyur, , £ In case of Union territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibition at @ For this revision for this designated location designated location under Date of exhibition at Electoral * Place, time and date of hearings as fixed by electoral registration officer rule 15(b) Registration Officer¶s Office under $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each designated rule 16(b) location # Give relationship as F-Father, M=Mother, and H=Husband within brackets i.e. -

DEVAKOTTAI MUNCIPALITY August, 2008

CITY CORPORATE CUM BUSINESS PLAN FINAL REPORT DEVAKOTTAI MUNCIPALITY August, 2008 Sponsored by Tamil Nadu Urban Infrastructure Financial Services Limited Government of Tamil Nadu Consultants FICHTNER Consulting Engineers (India) Private Ltd. Chennai – 600 028 CONTENTS I ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS II EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Page No 1 CONTEXT, CONCEPT AND CONTENTS OF CCCBP 1 1.1 Context of the Study 1 1.2 Objectives 1 1.3 Review meeting for Draft Final Reports 2 2 TOWN PROFILE, PHYSICAL PLANNING AND GROWTH MANAGEMENT 5 2.1 Regional Setting 5 2.2 Physical Features 5 2.3 Climate and Rainfall 5 2.4 History of the municipality 5 2.5 Demographic Features 6 2.5.1 Population and its growth 6 2.5.2 Population projection 6 2.5.3 Sex ratio and Literacy Rate 7 2.5.4 Density pattern 7 2.6 Occupational Pattern 7 2.7 Physical Planning and Growth Management 8 2.7.1 Land use and growth management 8 2.7.2 Growth Direction 9 2.7.3 Land Use Pattern 10 3 VISION AND STRATEGY 11 3.1 Stakeholders Workshop and Vision Statement 11 3.2 SWOT Analysis 12 3.3 Vision for Devakottai Town 12 3.4 Strategies for Economic Development 12 3.5 Urban Infrastructure 15 3.5.1 Vision 15 3.6 Performance and demand Assessment 16 3.7 Stratefies for Poverty Reduction and Slum Upgradation 18 3.8 Income Generation Activities 19 4 ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE 21 4.1 Elected Body 21 4.2 Executive Body 21 4.2.1 General Administration 22 4.2.2 Engineering Department 22 4.2.3 Accounts Department 22 4.2.4 Public Health Department 23 4.2.5 Town Planning Department 23 4.3 Staff Strength Position and Vacancy -

BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna

BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna University DAE5 May 2016 to September 2016 1 Figure 1 First courtyard of a Chettiar house in Kanadukathan (photo by M.SINOU) BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna University DAE5 May 2016 to September 2016 2 BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna University DAE5 May 2016 to September 2016 Content Part 2/3 Gallery ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Different attempts to protect the area........................................................................................................................................................ 13 A. Different type of projects ......................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Chettinad enhance via individual initiatives ................................................................................................................................................ 13 Chettinad enhance via institutions .............................................................................................................................................................. 13 B. An UNESCO application ............................................................................................................................................................................. 15 World Heritage -

Stamps of India - Commemorative by Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890

E-Book - 26. Checklist - Stamps of India - Commemorative By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 26. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 1st May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 76 Nos. YEAR PRICE NAME Mint FDC B. 1 2 3 1947 1 21-Nov-47 31/2a National Flag 2 15-Dec-47 11/2a Ashoka Lion Capital 3 15-Dec-47 12a Aircraft 1948 4 29-May-48 12a Air India International 5 15-Aug-48 11/2a Mahatma Gandhi 6 15-Aug-48 31/2a Mahatma Gandhi 7 15-Aug-48 12a Mahatma Gandhi 8 15-Aug-48 10r Mahatma Gandhi 1949 9 10-Oct-49 9 Pies 75th Anni. of Universal Postal Union 10 10-Oct-49 2a -do- 11 10-Oct-49 31/2a -do- 12 10-Oct-49 12a -do- 1950 13 26-Jan-50 2a Inauguration of Republic of India- Rejoicing crowds 14 26-Jan-50 31/2a Quill, Ink-well & Verse 15 26-Jan-50 4a Corn and plough 16 26-Jan-50 12a Charkha and cloth 1951 17 13-Jan-51 2a Geological Survey of India 18 04-Mar-51 2a First Asian Games 19 04-Mar-51 12a -do- 1952 20 01-Oct-52 9 Pies Saints and poets - Kabir 21 01-Oct-52 1a Saints and poets - Tulsidas 22 01-Oct-52 2a Saints and poets - MiraBai 23 01-Oct-52 4a Saints and poets - Surdas 24 01-Oct-52 41/2a Saints and poets - Mirza Galib 25 01-Oct-52 12a Saints and poets - Rabindranath Tagore 1953 26 16-Apr-53 2a Railway Centenary 27 02-Oct-53 2a Conquest of Everest 28 02-Oct-53 14a -do- 29 01-Nov-53 2a Telegraph Centenary 30 01-Nov-53 12a -do- 1954 31 01-Oct-54 1a Stamp Centenary - Runner, Camel and Bullock Cart 32 01-Oct-54 2a Stamp Centenary