ATINER's Conference Paper Series ARC2017-2393

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

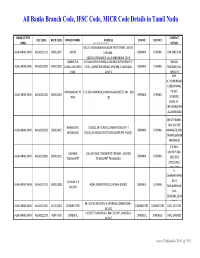

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

Kanadukathan) Address No

கானா翁கா鏍தா இரணி埍ககாவில் ꯁள்ளிகள் Sl. Permanent Address Present Residence Telephone Email Name No. (Kanadukathan) Address No. ID Sri. CT. Muthuraman No. 76. PL. M. CT. House. Ph: 04595-2S3014 KM. Street, 1 Kanadukathan – 630 103. Sivagangai Dist. Sri. CT. Palaniappan No. 76. PL. M. CT. House. Ph: 04595-2S3014 KM. Street, 2 Kanadukathan – 630 103. Sivagangai Dist. Sri. CT. Annamalai No. 14/8, T. KR. Street, Prajwal Vaigai Flats, Ph: 044-24794026 amalaichidambaram@gma il. Kanadukathan – 630 103. N0. 7/318-D, 2nd Main Road, Cell: 9444941149 com 3 Sivagangai Dist. Natesa Nagar, Virugambakkam, Cell : 9677207358 Chennai – 600 092. Sri. M. Chidambaram Flat No 1, Majestic Park, Ph: 044-23764992 48/9/1, Muthukumarappa Cell: 9445378472 4 Road, Saligramam, Chennai – 600 093. Sri. PL. Chidambaram Sree Sathiamurthy lllam, Ph: 04565-226237 No. 1580, Cell: 9442200046 Valluvar Nagar Main Street, 5 Sekkalai Kottai, Karaikudi – 630 002. Sri. A. Chidambaram No. 267/3, 2nd Main Road, Ph: 044-24793079 [email protected] Natesa Nagar, Virugambakkam, Cell : 9444058718 Chennai – 600 092. Cell: 9677048718 6 Smt. CT. Umayal: 9444625960 Selvi. CT. Valliammai: 9600012927 Sri. A. Senthilnathan Arunachalam, New GRT, Ph: 044-24797598 No. 254, 2nd Main Road, Cell: 9843228644 Natesa Nagar, Virugambakkam, Cell: 9486887310 7 Chennai – 600 092. Smt. S. Meenal: 9443037235 Sri. A. Selvakumar 54/18, Manali New Town, Cell: 9841342000 Chennai – 600 103. Cell: 9842108800 8 Cell: 9443140223 Sri. A. Lakshmanan 1570, SE Tradition Trace, Ph: (772)283-2057 [email protected] 34997 Stuart, Cell: 561-310-9681 9 Florida – USA. Cell: 561-801-2310 Zip code: 34997. -

District Census Handbook

Census of India 2011 TAMIL NADU PART XII-B SERIES-34 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SIVAGANGA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS TAMIL NADU CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 TAMIL NADU SERIES-34 PART XII - B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK SIVAGANGA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations TAMIL NADU MOTIF SIVAGANGA PALACE Sivaganga palace in Sivaganga Town was built near the Teppakulam has its historical importance. It is a beautiful palace, once the residence of the Zamindar of Sivaganga. The palace was occupied by the ex-rulers, one of the biggest and oldest, wherein Chinna Marudhu Pandiyar gave asylum to Veerapandiya Katta Bomman of Panchalankurichi when the British was trying to hang him as he was fighting against the colonial rule. There i s a temple for Sri Raja Rajeswari, inside the palace. CONTENTS Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 5 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 7 5 Brief History of the District 9 6 Administrative Setup 10 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 11 8 Important Statistics 12 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 16 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 21 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 35 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 55 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 63 (vi) Rural PCA-C.D. blocks wise Village Primary Census Abstract 71 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 163 Tables based on Households Amenities and Assets (Rural 10 Section –II /Urban) at District and Sub-District level. -

Chapter Iii 67

CHAPTER I I I THE TEMPLES AND THE SOCIAL ORGANISATION OF THE CHETTIARS ' In the last chapter we sav that the Ilayathankudi Nagarathar emerged as a distinct endogamous Saiva Vaisya sub-caste, consisting of the patrilineal groups, each group attached to a temple located in the vicinity of Illayathankudi, somewhere around the eighth century A.D. In this chapter we shall see that contrary to the vehe ment propa^nda about the regressive effects of Hindu religion and social organization on the rational pursuit of profit, with the Chettiars, their very'*^religious affiliation and their form of social organization seem to have been shaped by their economic interests. It is significant that the social organization of this sub caste crystallized at a period v^hen the Tamil Country was rocked by a massive wave of Hindu revivalism that had arisen to counter the rising tide of the heterodox faiths of Buddhism’and Jainism. Buddhists and Jains had flou rished amicably along with Hindu Sects even during the Sangam age. But when Buddhism got catapulted into ascendency, under the ’Kalabhras’ , ”a rather mysterious and ubiquitous enemy of civilization”, who swept over ’ the Tamil Country and ruled it for over the two hundred years following the close of the Sangam age in thz4e hurylred A . D . , a hectic fury of re lig io u s hatred and r iv alry 67 6^ was unleashed.^ The active propagation of Buddhism by the ruling Kalabhras, who are denounced in the Velvikudi grants of the Pandyas (nineth century) as evil kings (kali- arasar) who uprooted many adhirajas, and confiscated the pro- 2 perties gifted to Gods (temples) and Brahmins, provoked the adherents of Siva and Vishnu to make organized attempts to stall the rising tide of heresy. -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Tiruppattur Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 Jothika S SenthilKumar (F) 13-1-13, Pethatchi chettiar street, Kottaiyur, , 2 16/11/2020 PAVITHRA SIVARAJAN (H) 1-4-12B, KALIYAMMAN KOVIL, ALAGAPURI, , 3 16/11/2020 sebasthi clinton savarimuthu (F) 2/54, thalakkavur, karaikudi, , 4 16/11/2020 Azhagar Chinnappan (F) 8-23, Asari Theru, Ooranikarai, A.Kalappur, , 5 16/11/2020 Sarasu Azhagar (H) 8/23, Asari Theru, Ooranikarai, A.Kalappur, , 6 16/11/2020 sathishkumar periyandhavar balamani balamani, kilasevalpatti, periyandhavar (F) kilasevalpatti, , 7 16/11/2020 Swathi pillai daughter in law pillai (O) Rajamani Ammal Illam, manachai ,Thrichy main road, manachai village, , 8 16/11/2020 Shanmugi Shanmugi Periyannan Periyannan (F) 8, chithambaram ambalam theru, kottaiyur, , £ In case of Union territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibition at @ For this revision for this designated location designated location under Date of exhibition at Electoral * Place, time and date of hearings as fixed by electoral registration officer rule 15(b) Registration Officer¶s Office under $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each designated rule 16(b) location # Give relationship as F-Father, M=Mother, and H=Husband within brackets i.e. -

BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna

BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna University DAE5 May 2016 to September 2016 1 Figure 1 First courtyard of a Chettiar house in Kanadukathan (photo by M.SINOU) BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna University DAE5 May 2016 to September 2016 2 BUGEIA Camille Polytech Tours & Anna University DAE5 May 2016 to September 2016 Content Part 2/3 Gallery ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Different attempts to protect the area........................................................................................................................................................ 13 A. Different type of projects ......................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Chettinad enhance via individual initiatives ................................................................................................................................................ 13 Chettinad enhance via institutions .............................................................................................................................................................. 13 B. An UNESCO application ............................................................................................................................................................................. 15 World Heritage -

Review of Research

Review of ReseaRch HERITAGE TOURISM AROUND KARAIKUDI - A STUDY R. Radha1 and G. Poornima Thilagam2 issN: 2249-894X 1Teaching Assistant, Department of History, Alagappa impact factoR : 5.7631(Uif) University, Karaikudi. UGc appRoved JoURNal No. 48514 2 Teaching Assistant, Department of History, Alagappa volUme - 8 | issUe - 8 | may - 2019 University, Karaikudi. ABSTRACT: Karaikudi is a municipal town located in Sivaganga district of the state of Tamil Nadu. The place is the most famous in the entire municipality because it is also the largest town in the district. It is part of the Chettinad region that includes a total of 75 villages. The town is on the highway that connects Trichy and Rameshwaram. It is a well-known town in this southern state of India mainly because of the style of houses that is unique to the place. The houses in this town are constructed using the limestone that is called "karai veedu" in local language. Some people also believe that the town got its name from the plant of karai, which is found in abundance in the place. Karaikudi was earlier counted in the Ramanathapuram district and achieved the status of a municipality in 1928. Chettiars And Karaikudi It is a well-known fact that the family of Chettiars was instrumental in developing the town of Karaikudi. They have helped shape the town and brought it into prominence by building educational institutes, funding banks, constructing temples and celebrating festivals in the traditional ways. They have also taken upon them the onus of bringing social reforms. To make Karaikudi self-sufficient in every way, Vallal Alagappar, who belonged to the Chettiar family, established the Alagappa University in the place and this university has a good nationwide ranking. -

Mint Building S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU

pincode officename districtname statename 600001 Flower Bazaar S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Chennai G.P.O. Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Govt Stanley Hospital S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Mannady S.O (Chennai) Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Mint Building S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600001 Sowcarpet S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600002 Anna Road H.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600002 Chintadripet S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600002 Madras Electricity System S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Park Town H.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Edapalayam S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Madras Medical College S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600003 Ripon Buildings S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600004 Mandaveli S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600004 Vivekananda College Madras S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600004 Mylapore H.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Tiruvallikkeni S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Chepauk S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Madras University S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600005 Parthasarathy Koil S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 Greams Road S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 DPI S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 Shastri Bhavan S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600006 Teynampet West S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600007 Vepery S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600008 Ethiraj Salai S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600008 Egmore S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600008 Egmore ND S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600009 Fort St George S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600010 Kilpauk S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600010 Kilpauk Medical College S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600011 Perambur S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600011 Perambur North S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600011 Sembiam S.O Chennai TAMIL NADU 600012 Perambur Barracks S.O Chennai -

Download Download

Creative Space,Vol. 7, No. 1, July 2019, pp. 45–56 Vol.-7 | No.-1 | July 2019 Creative Space Journal homepage: https://cs.chitkara.edu.in/ Analyzing the Values in the Built Heritage of Chettinadu Region, Tamil Nadu, India Seetha RajivKumar1 and Thirumaran Kesavaperumal2 1Department of Architecture, National Institute of Technology, Tiruchirappalli, India Email: [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Received: June 18, 2019 Chettinadu, a region in southern India, is situated in Tamil Nadu State 32 km from the west coast of Revised: June 27, 2019 the Bay of Bengal with a total area of 1,550 square kilometers in the heart of Tamil Nadu. The built Accepted: July 5, 2019 heritage of Chettinadu is an irreplaceable cultural resource giving it a unique identity and character. In the tentative list of UNESCO 2014, the Chettinadu region has been classified into three clusters based Published online: July 11, 2019 on their Outstanding Universal Values and this provides a framework for our research.The region has experienced a tremendous amount of change from its original design and the old buildings are mirrors of the procession of history and culture that together have formed the heritage of the town. Well known Keywords: for its palatial mansions with their unique architectural style, the conservation of old buildings is a must Built Heritage, Architectural Values, Cultural in retaining the character of the city. In this paper we studied the historical background of heritage Values, Environmental Values, Chettinadu areas and buildings in the Chettinadu region and attempted to establish the values in the built heritage by means of a selected set of variables. -

1/14D,Chokkanatha Puram, 3Rd St, Vilangudi

Page 1 of 84 SL APP. CANDIDATE NAME NO NO AND ADDRESS RAJESHKUMAR P, S/O PITCHAIMANI V, 1 5828 3- 1/14D,CHOKKANATHA PURAM, 3RD ST, VILANGUDI, MADURAI-625018 RAJAVELU G, 2 5829 3/B, KASTHURI URAN ST., PALANGANATHAM, MADURAI- 625003 SAKTHIVEL A, S/O A.ALPATI, 3 5830 14 THIRISULAKALIAMMAN THERU, PALANGANATHAM, MADURAI-625003 RAJENDRAN B, S/O P BOSE, 4 5831 KOODAKOIL POST, TIRUMANGALAM TK, - MADURAI-0 MURUGAN P, NO.138, SAHAYARANI COMPD, MADHA KOIL STREET, 5 5832 FATHIMA NAGAR, BETHANIYAP URAM, MADURAI-625016 PITCHAI C, S/O C CHINNAPPAN, 6 5833 SOUTH STREET, SEDAPATTY PO, DINDIGUL-0 BALAMURUGAN M, S/O MUTHUMANI M, MUNIYANDI KOIL MAIN ST, 7 5834 KALLIKUDI, THIRUMANGALAM TK MADURAI-0 JEYA PRAKASH P, S/O S. PAULRAJ, 8 5835 1488, SOUTH STREET, KEELAKKOTTAI VGE, TIRUMANGALAM TK MADURAI-625704 MANIVANNAN G, S/O GANDHIRAJAN, THAVASIYENDALPATTY, 9 5836 KARUNKULAM PO, THIRUPPATHUR TK- SIVAGANGA-0 Page 2 of 84 SATHEESH P, S/O C PANDI, 1/56 THOPPAMPATTI, 10 5837 SAMIYAR PATTI POST, GANDHIGRAMAM VIA., ATTUR TK., DINDIGUL-624312 MURUGANANDHINI K, D/O KRISHNARAJ, 11 5838 52 AGRAHARAM, AVANIYAPURAM, MADURAI- 625011 MAHENDRAKUMAR V, S/O K.VARADHARAJAN, 12 5839 VELLAICHAMI NAICKER THOTTAM, KAPPALUR PO, TIRUMANGALAM TK- MADURAI-0 ARCHUNAN C, S/O CHINNASAMY, KANNIMAR KOIL ST, 13 5840 BATLAGUNDU, NILAKOTTAI TK- DINDIGUL. KARTHICK PL, S/O.PALANIYAPPAN,, 14 5841 24 PANDIAN NAGAR,, KARAIKUDI PO,TK,, SIVAGANGA-0 SRINIVASAN.G, NO.37- P/2-3, VADAMADURAI, 15 5842 VADAMADURAI PORURATCHI, VEDASANTHUR T.K., DINDIGUL-624802 PARAMES .V, S/O VEERAIAH GOUNDER, 16 5843 KURUMBAPATTI, PAGANATHAM PO, VEDASENDUR TK, DINDIGUL. -

Chapter 4.1.9 Ground Water Resources Sivagangai

CHAPTER 4.1.9 GROUND WATER RESOURCES SIVAGANGAI DISTRICT 1 INDEX CHAPTER PAGE NO. INTRODUCTION 3 SIVGANGAI DISTRICT – ADMINISTRATIVE SETUP 3 1. HYDROGEOLOGY 3-7 2. GROUND WATER REGIME MONITORING 8-15 3. DYNAMIC GROUND WATER RESOURCES 15-24 4. GROUND WATER QUALITY ISSUES 24-25 5. GROUND WATER ISSUES AND CHALLENGES 25-26 6. GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT AND REGULATION 26-32 7. TOOLS AND METHODS 32-33 8. PERFORMANCE INDICATORS 33-36 9. REFORMS UNDERTAKEN/ BEING UNDERTAKEN / PROPOSED IF ANY 10. ROAD MAPS OF ACTIVITIES/TASKS PROPOSED FOR BETTER GOVERNANCE WITH TIMELINES AND AGENCIES RESPONSIBLE FOR EACH ACTIVITY 2 GROUND WATER REPORT OF SIVAGANGAI DISTRICT INRODUCTION : In Tamil Nadu, the surface water resources are fully utilized by various stake holders. The demand of water is increasing day by day. So, groundwater resources play a vital role for additional demand by farmers and Industries and domestic usage leads to rapid development of groundwater. About 63% of available groundwater resources are now being used. However, the development is not uniform all over the State, and in certain districts of Tamil Nadu, intensive groundwater development had led to declining water levels, increasing trend of Over Exploited and Critical Firkas, saline water intrusion, etc. ADMINISTRATIVE SET UP The geographical extent of Sivagangai District is 4, 18,900 hectares or 4,189 sq.km. Accounting for 3.22% of the geographical area of Tamilnadu State. The district has well laidout roads and railway lines connecting all major towns within and outside the State for administrative purpose. For administrative purpose , the district has been divided into 6 Taluks, 12 Blocks and 38 Firkas. -

Department of History

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY RANK HOLDERS 2005-2006 S.Selvarani III Rank T.Usharani V Rank T.Manimaran VII Rank 2008-2009 A.Arumugam I Rank DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY History of the Department Name of the Course B.A. History (Aided) Year of Establishment 1981 Affiliation Granted by Madurai University, Madurai Presently Affiliated to Alagappa University, Karaikudi DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Faculty Members Sl. No. Name Qualification Designation Area of Specialization 1 Dr.D.K.Venkatachalapathy M.A.,M.Phil., Ph.D., Associate Professor Ancient Dip. in Archaeology and Head of the History Department 2 Associate Professor Modern History Ms. D. Arulmoni Gunavathi M.A.,M.Phil., in History Assistant Professor Modern History 3 Ms.T.Dhanalakshmi M.A.,M.Phil., of History 4 Ms.M.Muthulakshmi M.A.,M.Phil., PTA Guest Lecturer Modern History There are three aided staff members and one unaided staff member, who is paid by the management. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY FACILITIES Library Reference and Text books are kept in the library. Text books are issued to the students. Every year library is updated with newer books. Department Library Books in the department library include reference and text books. Maps Historical maps are kept in the department for better learning. Number of History books in the General Library 1800 Number of History books in the Department Library 301 Number of Maps in the Department 44 The available ICT tools are used in the Teaching-Learning process. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ACTIVITIES 1. Dr.D.K.Venkatachalapathy :Pursued his part time doctoral research and received his doctoral degree from M.K.University on Dec.2008 for his thesis entitled “Folk Religion of Sivaganga District in Tamilnadu: A Cultural Historical Study”.