Papists” and Prejudice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tablet Features Spread 14/04/2020 15:17 Page 13

14_Tablet18Apr20 Diary Puzzles Enigma.qxp_Tablet features spread 14/04/2020 15:17 Page 13 WORD FROM THE CLOISTERS [email protected] the US, rather than given to a big newspaper, Francis in so that Francis could address the people of God directly, unfiltered. He had been gently the garden rebuffed. So the call from the Pope’s Uruguayan priest secretary, Fr Gonzalo AUSTEN IVEREIGH tells us he was in his Aemilius, a week later was a delightful shock: garden and just about to plant a large jasmine “Would it be alright if the Holy Father when the audio file arrived in his inbox. It recorded his answers to your questions?” The was the voice of Pope Francis, who had complete interview appeared in last week’s agreed to record his answers to the questions Easter issue of The Tablet. Ivereigh had put to him about navigating our way through the coronavirus storm. LAST YEAR Austen and his wife Linda and Ivereigh decided to put his headphones on their dogs deserted south Oxfordshire for a and listen to the Pope speaking to him while small farm near Hereford, with charmingly he was digging. By the time the plant was decayed old barns and 15 acres of grass mead- in the ground, watered and mulched, Francis ows, at the edge of a hamlet off a busy road was still only halfway through the third to Wales. He blames Laudato Si’ . The Brecon answer. “I checked the recording,” Austen Ivereigh, who was deputy editor of The Beacons beckon from a far horizon; the Wye, says, “46 minutes!” Tablet in the long winter of the John Paul II swelled by fast Welsh rivers, courses close by; “By the end I was stunned. -

Mary and the Catholic Church in England, 18541893

bs_bs_banner Journal of Religious History Vol. 39, No. 1, March 2015 doi: 10.1111/1467-9809.12121 CADOC D. A. LEIGHTON Mary and the Catholic Church in England, 1854–1893 The article offers description of the Marianism of the English Catholic Church — in particular as manifested in the celebration of the definition of the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception in 1854 and the solemn consecration of England to the Virgin in 1893 — in order to comment on the community’s (and more particularly, its leadership’s) changing perception of its identity and situation over the course of the later nineteenth century. In doing so, it places particular emphasis on the presence of apocalyptic belief, reflective and supportive of a profound alienation from con- temporary English society, which was fundamental in shaping the Catholic body’s modern history. Introduction Frederick Faber, perhaps the most important of the writers to whom one should turn in attempting to grasp more than an exterior view of English Catholicism in the Victorian era, was constantly anxious to remind his audiences that Marian doctrine and devotion were fundamental and integral to Catholicism. As such, the Mother of God was necessarily to be found “everywhere and in everything” among Catholics. Non-Catholics, he noted, were disturbed to find her introduced in the most “awkward and unexpected” places.1 Faber’s asser- tion, it might be remarked, seems to be extensively supported by the writings of present-day historians. We need look no further than to writings on a sub-theme of the history of Marianism — that of apparitions — and to the period spoken of in the present article to make the point. -

The Tablet June 2011 Standing of Diocese’S Schools and Colleges Reflected in Rolls

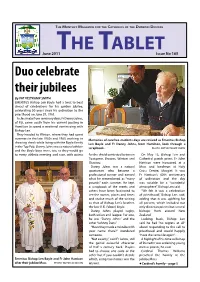

THE MON T HLY MAGAZINE FOR T HE CA T HOLI C S OF T HE DUNE D IN DIO C ESE HE ABLE T June 2011T T Issue No 165 Duo celebrate their jubilees By PAT VELTKAMP SMITH EMERITUS Bishop Len Boyle had a treat to beat ahead of celebrations for his golden jubilee, celebrating 50 years since his ordination to the priesthood on June 29, 1961. A classmate from seminary days, Fr Danny Johns, of Fiji, came south from his current posting in Hamilton to spend a weekend reminiscing with Bishop Len. They headed to Winton, where they had spent summers in the late 1950s and 1960, working in Memories of carefree students days are revived as Emeritus Bishop shearing sheds while living with the Boyle family Len Boyle and Fr Danny Johns, from Hamilton, look through a in the Top Pub. Danny Johns was a natural athlete scrapbook. PHOTO: PAT VELTKAMP SMITH and the Boyle boys were, too, so they would go to every athletic meeting and race, with points for the shield contested between On May 13, Bishop Len and Tuatapere, Browns, Winton and Cathedral parish priest Fr John Otautau. Harrison were honoured at a Danny Johns was a natural Mass and luncheon at Holy sportsman who became a Cross Centre, Mosgiel. It was professional runner and earned Fr Harrison’s 40th anniversary what he remembered as “many of ordination and the day pounds’’ each summer. He kept was notable for a “wonderful a scrapbook of the meets and atmosphere”, Bishop Len said. others have been fascinated to “We felt it was a celebration see the names, places and times of priesthood,” Bishop Len said, and realise much of the writing adding that it was uplifting for as that of Bishop Len’s brother, all present, which included not the late V. -

Tablet Features Spread

175 YEARS – 50 GREAT CATHOLICS / Carmen Mangion on Sr Mary Clare Moore Born in Dublin To mark our anniversary, we have invited 50 Catholics to choose adored. In October 1854 she led on 20 March a person from the past 175 years whose life has been a personal a party of four Bermondsey sisters 1814, Georgiana inspiration to them and an example of their faith at its best to join Nightingale to nurse in the Moore converted Crimea. Jerry Barrett’s painting to Catholicism the first four women to join her, the leaders that founded nine Mission of Mercy: Florence with her mother taking the name Mary Clare. Convents of Mercy in England. Nightingale receiving the wounded in 1823. Aged Aged 23, Moore became supe- She worked well with the at Scutari (in the National Portrait 14, she was rior of the Cork convent. Then in English hierarchy, becoming a Gallery) gives us our only contem- employed by the founder of the 1839, she was lent to the first close and trusted confidante of porary image of her. Her face, like Sisters of Mercy, Catherine English foundation in the slums Thomas Grant, the Bishop of her life, is in the shadows. McAuley, as a governess but was of Bermondsey, south London. Southwark. Her letters to her sis- Mary Clare Moore died of soon drawn by her House of She managed the Convent of ters reflect her compassion and pleurisy in 1874, aged only 60, Mercy, a refuge and school for Mercy in Bermondsey until her encouragement. She wrote to con- but worn out by her exertions on impoverished female servants death in 1874. -

Jesus Christ's Sufferings and Death in the Iconography of the East and the West

Скрижали, 4, 2012, с. 122-138 V.V.Akimov Jesus Christ's sufferings and death in the iconography of the East and the West The image of God sufferings, Jesus Christ crucifixion has received such wide spreading in the Christian world that is hardly possible to count up total of the similar monuments created throughout last one and a half thousand of years. The crucifixion has got a habitual symbol of Christianity and various types of the Crucifix became a distinctive feature of some Christian faiths. From time to time modern Christians, looking at the Cross with crucified Jesus Christ, don’t think of the tragedy of Christ’s death and the joy of His resurrection but whether the given Crucifix is «their own» or «another's». Meanwhile, the iconography of the Crucifix as far as the iconography of God’s Mother can testify to a generality of Christian tradition of the East and the West. There are much more general lines than differences between them. The evangelical narration of God sufferings and the history of Crucifix iconography formation, both of these, testify to the unity of east and western tradition of the image of the Crucifixion. Traditions of the East and the West had one source and were in constant interaction. Considering the Crucifix iconography of the East and the West in a context of the evangelical narration and in a historical context testifies to the unity of these traditions and leads not to dissociation, conflicts and mutual recriminations, but gives an impulse to search of the lost unity. -

Catholicism and European Politics: Introducing Contemporary Dynamics

religions Editorial Catholicism and European Politics: Introducing Contemporary Dynamics Michael Daniel Driessen Department of Political Science and International Affairs, John Cabot University, 00165 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 1. Introduction Recent research on political Catholicism in Europe has sought to theorize the ways in which Catholic politics, including Catholic political parties, political ideals, and political entrepreneurs, have survived and navigated in a post-secular political environment. Many of these studies have articulated the complex ways in which Catholicism has adjusted and transformed in late modernity, as both an institution and a living tradition, in ways which have opened up unexpected avenues for its continuing influence on political practices and ideas, rather than disappearing from the political landscape altogether, as much Citation: Driessen, Michael Daniel. previous research on religion and modernization had expected. Among other things, this 2021. Catholicism and European new line of research has re-evaluated the original and persistent influence of Catholicism Politics: Introducing Contemporary on the European Union, contemporary European politics and European Human Rights Dynamics. Religions 12: 271. https:// discourses. At the same time, new political and religious dynamics have emerged over doi.org/10.3390/rel12040271 the last five years in Europe that have further challenged this developing understanding of contemporary Catholicism’s relationship to politics in Europe. This includes the papal Received: 26 March 2021 election of Pope Francis, the immigration “crisis”, and, especially, the rise of populism and Accepted: 6 April 2021 new European nationalists, such as Viktor Orbán, Jaroslaw Kaczynski and Matteo Salvini, Published: 13 April 2021 who have publicly claimed the mantles of Christian Democracy and Catholic nationalism while simultaneously refashioning those cloaks for new ends. -

The Tablet,” and Handed It Farewelled Stuart at a Lunch on Friday, Over Weed Free and Blooming

THE MONTHLY MAGAZINE FOR THE CATHOLICS OF THE DUNEDIN DIOCESE HE ABLET FebruaryT 2013 T Issue No 183 Refurbished St Mary’s School, Mosgiel The official opening ceremony of Mihi Whakatau, Blessing and Dedication took place at St Mary’s School, Mosgiel, on Friday 8th February 2013. Addressing the large gathering of school community and invited guests, Bishop Colin said, “We are fortunate with this lovely site as it has been dedicated over long years to educational use; the students will be learning in a scholastic atmosphere that has seen the education of NZ clergy for nigh on a hundred years. We are truly blessed.” He went on to speak of the nearby parish church, which was the Holy Cross Chapel, built and opened in 1963 when he was the junior Sacristan. “I encourage stopping faith and education at work together. the children, families and staff in for a It is all about the Catholic character of to make use of it, not only for school prayer before school and asking God’s our schools, based on the values and and class liturgies, but to make visits help with their work - a wonderful teaching of Jesus and his Church.” to Our Lord regularly on a daily basis. custom from the past. This spells out See feature on page 7 ➤ I look forward to seeing the children in a special way a fullness and bond of General Manager, on Sabbatical Leave Gillian planted Stuart Young, Diocesan General has felt drawn towards priesthood and Manager, has been granted leave to during recent years he has immersed a fine garden attend the national Seminary this year. -

Vestments Are More Than Just Clothes for the Pope Sunday, April 13, 2008 by DAVID GIBSON

Vestments are more than just clothes for the pope Sunday, April 13, 2008 BY DAVID GIBSON During Pope Benedict XVI's visit this week, the first since his election three years ago, Catholics will listen intently to what he says, and how he says it, all in hopes of figuring out if Joseph Ratzinger has indeed become a kindly German shepherd or whether he remains God's Rottweiler, one of the many monikers he earned during a long tenure as the Vatican's doctrinal watchdog. Yet as important as Benedict's words will be in introducing the pope to an American audience that knows little about him, it may be just as important to check out what he's wearing. No, not the red Prada shoes that set tongues wag ging early on in his pontificate. (Besides, the designer kicks were apparently knockoffs by the papal cobbler.) Of greater import than Benedict's shoes or his sunglasses (rumored to be Serengetis by Bushnell) will be his choice of liturgical vestments and other papal accouterments, choices that speak volumes not only about his personal tastes but also about his vision of the church's future and its past. With increasing regularity, Benedict has been reintroducing elaborate lace garments and monarchical regalia that have not been seen around Rome in decades, even centuries. He has presided at mass using the wide cope (a cape so ample it is held up by two attendants) and high mitre of Pius IX, a 19th-century pope known for his dim views of the modern world, and on Ash Wednesday he wore a chasuble modeled on one worn by Paul V, a Borghese pope of the 17th century remembered for censuring Galileo. -

Downloaded from the Website of the Anglican-Roman Catholic Theological Consultation in the United States of America (ARCUSA) At

Downloaded from the website of the Anglican-Roman Catholic Theological Consultation in the United States of America (ARCUSA) at http://arcusa.church First published as “Anglican Ordinariates: A New Form of Uniatism?” Ecumenical Trends 40:8 (September 2011), pp. 118-126. The National Workshop on Christian Unity Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, May 11, 2011 What is Uniatism? An exploration of the concept of uniatism in relation to the creation of the Anglican Ordinariates By Rev. Ronald G. Roberson, CSP With a Response by Rev. James Massa In this seminar Fr James Massa and I will be looking at the theme, “The Anglican Ordinariates: A New Form of Uniatism?” This has to do with the Apostolic Constitution Anglicanorum Coetibus of November 2009, in which Pope Benedict XVI provided for the establishments of personal ordinariates for former Anglicans that will retain elements of the Anglican patrimony. After the document was released, some claimed that this was a new form of uniatism, which has long been a major stumbling block in relations between Catholics and Orthodox. There was a fear that these new structures might seriously set back relations between Catholics and Anglicans as well. So my first task here will be to answer the question, “what is uniatism?” It’s a concept that until now has been used exclusively in the context of the Christian East, and more specifically with regard to the Eastern Catholic Churches. To get a handle on this very complicated concept, I will first examine the historical circumstances in which these Eastern Catholic churches came into existence. With that in mind, we can then clarify what is meant by the term “uniatism,” both in ordinary usage and as it was defined by the international Catholic-Orthodox dialogue. -

Inspiration from a Bold Mystic

19-22 Tablet 11 Aug 07 BooksLL 8/8/07 3:20 pm Page 1 BOOKS AUSTEN IVEREIGH Desolata, one both intimate and empty; and she is Theotokos, mother of God, the per- sonification of the Scriptures. Lubich on INSPIRATION Mary often hits notes of extravagance: she is “the flower blossoming on the tree of humanity, born of God who created the first seed in Adam. FROM A BOLD She is the daughter of God her Son” – which some may think best confined to a spiritual MYSTIC diary. But she can equally strike on something apparently straightforward – “do to others what would you have them do to you” – and flesh Chiara Lubich, Essential Writings: out a whole practical programme for living. spirituality, dialogue, culture The second part of the book is a series of Compiled and ed. Michel Vandeleene insights for such a programme. In one essay NEW CITY PRESS, £12.40 she suggests asking yourself, when you meet ■ Tablet bookshop price £11.20 Tel 01420 592974 someone, what they are going through, and keep loving them until you find that same suf- fering in yourself. “Love will suggest to me how ith 140,000 members worldwide, I can help them,” she says, “because as Chris- and another 2 million connected tians we know the value of suffering.” Spend in other ways through its prayer Chiara Lubich, founder of the Focolare one day doing this, Chiara insists, and “a joy W groups, ecumenical and interfaith movement, receiving an honorary we have never felt before will flood over us. meetings – not to mention its 20-odd towns doctorate from the Catholic University A new power will fill us. -

Victory and the Cross Last Sunday We Celebrated Jesus' Resurrection And

Victory and the Cross Last Sunday we celebrated Jesus’ resurrection and we talked briefly about his death by crucifixion. This morning I want to focus our attention on what actually happened on the cross. I don’t mean physically to Jesus, but spiritually to us. What does it mean to us and for us that Jesus’ died on the cross? What was accomplished on the cross? The bible says in Colossians 2:15 that Jesus “disarmed the powers and authorities, [making] a public spectacle of them, triumphing over them by the cross.” Colossians 2:15. Look at those words “disarmed” and “triumph” and tell me, what’s wrong with this picture? Is there anything about Jesus’ trial, torture and death by crucifixion that looks triumphant? Beaten, bleeding, nailed to a cross, struggling for breath, his life slipping away. Nothing points to victory. Jesus is the public spectacle, not the devil. The only victory appears to be that of evil over good. But while the world sees a dying man, we see a kinsman redeemer, taking our place to set us free from sin’s bondage. Rome sees a criminal paying for his crimes, but we see the One who knew no sin becoming sin for us so we could become the righteousness of God in Christ. Something else was happening on that cross. How did it all happen and what does that victory mean for us? Let’s look at how this unfolds through the ages. Victory Predicted. I hesitate to use the word predicted because it might imply the possibility it wouldn’t happen. -

The Franciscan Friars in Britain Since 1829 It Has Always Been Difficult To

The Franciscan Friars in Britain Since 1829 It has always been difficult to answer the question, “What do Franciscans do?” for they exercise a variety of ministries and exclude very little. The answer given in the documents of the Order today is that they are an evangelising fraternity, but for what that means in practice, and Franciscanism has always been eminently practical, it is most instructive to look at what Franciscans have done in these lands. The English Franciscan Province began in 1224, with the friars establishing their first residence in Canterbury at the time St. Francis received the Stigmata on Mount La Verna. From the small group of nine who arrived, the Province grew with breathtaking rapidity. Within fifty years it contained 1,500 friars. That medieval province gave glory to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge and provided the Church with luminaries such as John Duns Scotus, Roger Bacon and William of Ockham. If the medieval period provided the province with thinkers, the Reformation gave it heroes: the Observant Franciscans were the first religious to be attacked and dissolved by Henry VIII (not surprising since they lived next door to his palace in Greenwich and in his presence one compared his marriage to Anne Boleyn with that of Ahab to Jezebel!). Many were imprisoned, martyred or exiled. Restored under Mary, the friars were again expelled by Elizabeth, and relocated to Douai in northern France, whence they sent missionaries to England, providing an uninterrupted presence throughout penal times. The French Revolution deprived the English friars of their base at Douai and the Province, unable to establish a stable novitiate and student house, went into decline.