Mary and the Catholic Church in England, 18541893

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men of God Homosexual and Catholic Identity Negotiation, Through Holland‟S Catholic Priests Kyle Alexander SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2011 Men of God Homosexual and Catholic Identity Negotiation, Through Holland‟s Catholic Priests Kyle Alexander SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Alexander, Kyle, "Men of God Homosexual and Catholic Identity Negotiation, Through Holland‟s Catholic Priests" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1092. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1092 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MenHomosexual of and God Catholic Identity Negotiation, Through Holland‟s Catholic Priests Kyle Alexander Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Netherlands: International perspectives on sexuality & gender, SIT Study Abroad, Spring 2011 University Affiliation: Fordham University, Departments of Psychology and Sociology Author: Alexander, Kyle Academic Director: Kevin Connors, Advisor: Balázs Boross Europe, Netherlands, Amsterdam Men of God 2 Consent to Use of Independent Study Project (ISP) Student Name: Kyle Alexander Title of ISP: Return of the Faithful. Examining the Contemporary Dutch Gay, Catholic Male. Program and Term: Netherlands: International perspectives on sexuality & gender. Fall 2010 1. When you submit your ISP to your Academic Director, World Learning/SIT Study Abroad would like to include and archive it in the permanent library collection at the SIT Study Abroad program office in the country where you studied and/or at any World Learning office. -

Politics of Identity

v Politics of Identity What Next after Multiculturalism May 2015 Summary Vít Novotný1 The failure of multiculturalism has been declared by many. Yet few have come up with alternatives to how Europe’s ethnic and religious groups can co-exist in our liberal democracies. This InFocus argues that Europe can benefit from the genuine desire that many immigrants have, to identify with the constitutions of their new home countries while maintaining elements of their own culture. European and national policymakers should elaborate on the existing concept of interculturalism, and they could learn from the US and Canadian approaches to integration. Europe’s centre-right political parties have a particular role not only in opening politics to immigrants and their descendants but also in forging strong national and European allegiances that are compatible with group belonging.1 Introduction The jihadist terror attacks in Paris and Copenhagen in early 2015 starkly reminded us that not all is well with the integration of Muslims into European societies. Paradoxically, the public demonstrations in France that followed the attacks injected a degree of optimism into European public life. These moving and encouraging public displays demonstrated beyond doubt that France continues to be a country of liberty. The 3.7 million people who were on the streets also proved, in their support for tolerance and freedom of speech, that liberal democracy is not dead. 1 I am grateful to Roland Freudenstein for his extensive comments that significantly improved the argument of this paper. I would also like to thank Michael Benhamou for his remarks. Nevertheless, if anyone still had doubts, European liberal democracy is facing a number of external and internal tests. -

Tablet Features Spread 14/04/2020 15:17 Page 13

14_Tablet18Apr20 Diary Puzzles Enigma.qxp_Tablet features spread 14/04/2020 15:17 Page 13 WORD FROM THE CLOISTERS [email protected] the US, rather than given to a big newspaper, Francis in so that Francis could address the people of God directly, unfiltered. He had been gently the garden rebuffed. So the call from the Pope’s Uruguayan priest secretary, Fr Gonzalo AUSTEN IVEREIGH tells us he was in his Aemilius, a week later was a delightful shock: garden and just about to plant a large jasmine “Would it be alright if the Holy Father when the audio file arrived in his inbox. It recorded his answers to your questions?” The was the voice of Pope Francis, who had complete interview appeared in last week’s agreed to record his answers to the questions Easter issue of The Tablet. Ivereigh had put to him about navigating our way through the coronavirus storm. LAST YEAR Austen and his wife Linda and Ivereigh decided to put his headphones on their dogs deserted south Oxfordshire for a and listen to the Pope speaking to him while small farm near Hereford, with charmingly he was digging. By the time the plant was decayed old barns and 15 acres of grass mead- in the ground, watered and mulched, Francis ows, at the edge of a hamlet off a busy road was still only halfway through the third to Wales. He blames Laudato Si’ . The Brecon answer. “I checked the recording,” Austen Ivereigh, who was deputy editor of The Beacons beckon from a far horizon; the Wye, says, “46 minutes!” Tablet in the long winter of the John Paul II swelled by fast Welsh rivers, courses close by; “By the end I was stunned. -

DIOCESE of EAST ANGLIA (Province of Westminster) Charity No

DIOCESE OF EAST ANGLIA (Province of Westminster) Charity No. 278742 Website: www.rcdea.org.uk Twinned with The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem & The Apostolic Prefecture of Battambang, Cambodia PATRONS OF THE DIOCESE Our Lady of Walsingham, 24th September St Felix, 8th March St Edmund, 20th November St Etheldreda, 23rd June BISHOP Rt. Rev. Alan Stephen Hopes BD AKC Bishop’s Residence: The White House, 21 Upgate, Poringland, Norwich, Norfolk NR14 7SH. Tel: (01508) 492202 Fax:(01508) 495358 Email: [email protected] Cover Illustration: The illustration on the front cover shows Pope Francis before the Holy Door to announce the Jubilee Year of Mercy (copyright: L’Osservatore Romano) Map of the Diocese.........................................................................................4 Foreword by the bishop..................................................................................5 Pope Francis reflects on the Jubilee Year of Mercy......................................7 Telephone Numbers........................................................................................9 Convents.......................................................................................................12 Schools.........................................................................................................13 Dates for your Diary.....................................................................................15 The Pope and National Hierarchy................................................................17 The Diocese..................................................................................................20 -

An Assessment of Religious Segregation in Northern Ireland's Schools

Stockholm Research Reports in Demography | no 2021:15 An Assessment of Religious Segregation in Northern Ireland’s Schools Brad Campbell ISSN 2002-617X | Department of Sociology 1 An Assessment of Religious Segregation in Northern Ireland’s Schools Brad Campbell Stockholm University Queen’s University Belfast Abstract Reflecting the deep ethno-national differences that exist between the Protestant-British and Catholic-Irish communities in Northern Ireland, a considerable wealth of knowledge exists on the nature and intensity of residential segregation. However, in contrast there have been relatively few empirical studies undertaken to quantify the scale and intensity of religious segregation between Protestant and Catholic pupils in Northern Ireland’s schools. This paper aims to contribute to the literature by using school census data from the Department of Education (DoE) for the school year 2018/19 to investigate religious segregation from several perspectives including (1) educational stage, (2) school type and (3) by pupils’ religion. The analysis will adopt well established indices to capture two dimensions of segregation; firstly, population unevenness to measure the intensity of segregation between Protestant and Catholic pupils using the index of dissimilarity (D) and the degree of unevenness by each religious and non-religious group using the segregation index (IS). The second dimension – social exposure will be used measured using the interaction index (P*x) to explore the intra group inter-group contact. The main findings from this study are that primary schools are more segregated than post-primary attributed to smaller, more localised catchment area and the influence of familial ties. The Protestant “Controlled” sector is less segregated than the Catholic “Maintained” sector due to a more religiously diverse intake. -

Language of Hope in Europe

Journal of Christian Education in Korea Vol. 65(2021. 3. 30) : 29-54 DOI: 10.17968/jcek.2021..65.002 Language of Hope in Europe Monique van Dijk-Groeneboer (Professor, Tilburg University, The Netherlands) Michal Opatrny (Professor, South Bohemian University, Budojevice Czech Republic) Eva Escher (Professor, University of Erfurt, Germany) Abstract In Europe, the diversity in religions, cultures, languages and historical backgrounds is enormous. World War II and the Soviet Regime have played a large part in this and the flow of refugees from other continents in- creases the pluralism. How can religious education add to bridging between differences? The language across European countries is different, literally between countries, but also figuratively speaking and even inside individual countries. These differences occur in cultural sense and across age groups as well. Secondary education has the task to form young people to become firmly rooted people who can hold their own in society. It is essential that they learn to examine their own core values and their roots. Recognising their values should be a main focus of religious education. However, schools are currently accommodating increasing numbers of non-religious pupils. What role do religious values still play in this situation? How do pupils feel about active involvement in religious institutions, and about basing life choices on religious beliefs? Can other, non-religious values be detected which could form the basis for value-oriented personal formation? Research of these subjects has been ongoing in the Netherlands for more than twenty years and is currently being expanded to the Czech Republic 30 Journal of Christian Education in Korea and(former East) Germany. -

Kuyper and Apartheid: a Revisiting

Kuyper and Apartheid: A revisiting Patrick Baskwell (Brandon, Florida, USA)1 Research Associate: Department of Dogmatics and Christian Ethics University of Pretoria Abstract Was Abraham Kuyper, scholar, statesman, and university founder, the ideological father of Apartheid in South Africa? Many belief so. But, there are others, amongst them George Harinck of the Free University in Amsterdam, who don’t think so. The article argues that there is an element of truth in both opinions. Kuyper did exhibit the casual racism so characteristic of the Victorian era, with its emphasis on empire building and all that it entailed. Kuyper was also directly responsible, ideologically, for the social structure in the Netherlands known as “verzuiling” or “pillarization” in terms of which members of the Catholic, Protestant, or Socialist segments of society had their own social institutions. This pillarizing, or segmenting, of society was, however, always voluntary. This is not true of the pillarizing or segmenting of South African society known as Apartheid. While there are similarities between Apartheid and “verzuiling”, especially in their vertical partitioning of the individual’s entire life, the South African historical context, the mediation of Kuyper’s ideas through South African scholars, the total government involvement, and therefore, the involuntary nature of Apartheid, point to their inherent dissimilarity. Apartheid was simply not pure Kuyper. Hence, while the effects of Kuyper’s ideas are clearly discernable in Apartheid policy, the article aims at arguing that Kuyper cannot be considered the father of Apartheid in any direct way. 1. INTRODUCTION In a recent article, George Harinck, director of the Historisch Documentatiecentrum voor het Nederlands Protestantisme (1800-current) at the Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, describes the beginnings of his research for a book on Abraham Kuyper. -

The Tablet June 2011 Standing of Diocese’S Schools and Colleges Reflected in Rolls

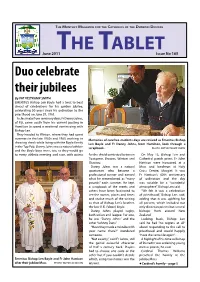

THE MON T HLY MAGAZINE FOR T HE CA T HOLI C S OF T HE DUNE D IN DIO C ESE HE ABLE T June 2011T T Issue No 165 Duo celebrate their jubilees By PAT VELTKAMP SMITH EMERITUS Bishop Len Boyle had a treat to beat ahead of celebrations for his golden jubilee, celebrating 50 years since his ordination to the priesthood on June 29, 1961. A classmate from seminary days, Fr Danny Johns, of Fiji, came south from his current posting in Hamilton to spend a weekend reminiscing with Bishop Len. They headed to Winton, where they had spent summers in the late 1950s and 1960, working in Memories of carefree students days are revived as Emeritus Bishop shearing sheds while living with the Boyle family Len Boyle and Fr Danny Johns, from Hamilton, look through a in the Top Pub. Danny Johns was a natural athlete scrapbook. PHOTO: PAT VELTKAMP SMITH and the Boyle boys were, too, so they would go to every athletic meeting and race, with points for the shield contested between On May 13, Bishop Len and Tuatapere, Browns, Winton and Cathedral parish priest Fr John Otautau. Harrison were honoured at a Danny Johns was a natural Mass and luncheon at Holy sportsman who became a Cross Centre, Mosgiel. It was professional runner and earned Fr Harrison’s 40th anniversary what he remembered as “many of ordination and the day pounds’’ each summer. He kept was notable for a “wonderful a scrapbook of the meets and atmosphere”, Bishop Len said. others have been fascinated to “We felt it was a celebration see the names, places and times of priesthood,” Bishop Len said, and realise much of the writing adding that it was uplifting for as that of Bishop Len’s brother, all present, which included not the late V. -

Religion and Socialism in the Long 1960S: from Antithesis to Dialogue in Eastern and Western Europe

Contemporary European History (2020), 29, 127–138 doi:10.1017/S0960777320000077 INTRODUCTION Religion and Socialism in the Long 1960s: From Antithesis to Dialogue in Eastern and Western Europe Heléna Tóth and Todd H. Weir History Department, Otto-Friedrich-University, Fischstrasse 5/7, 96047 Bamberg, Germany [email protected] One of the most remarkable transformations of European society and politics during the Cold War period was in relations between socialism and religion. Extreme hostility between revolutionary socialism and Christianity had been a structural component of major political conflicts in the trans-war period of 1914 to 1945. With an eye to violence against churches in Mexico, Spain and the Soviet Union, Pope Pius XI had declared in 1937 that ‘for the first time in history we are witnessing a struggle, cold-blooded in purpose and mapped out to the least detail, between man and “all that is called God”’. Upon the German invasion of his native Netherlands in 1940, Europe’s leading ecumenical spokesman Willem Visser ’t Hooft similarly spoke of the Christian struggle against godlessness as ‘a war behind the war’ that had begun ‘long before September 1939 and will certainly go on long after an armistice has been con- cluded’.1 This hostility flowed into the accelerating polarisation of European politics and diplomacy in the immediate post-war period that led to the Cold War.2 Events such as the exchange of letters between US President Harry S. Truman and Pope Pius XII in 1946 confirming the Christian core of Western civilisa- tion or the show trial of Cardinal József Mindszenty in Hungary in 1949 were moments of deep symbolic significance that welded religion to the solidifying political rhetoric.3 As Dianne Kirby writes, ‘for many who lived through the period, the Cold War was one of history’s great religious wars, a global conflict between the god-fearing and the godless’.4 In the 1960s, however, the situation changed dramatically. -

Tablet Features Spread

175 YEARS – 50 GREAT CATHOLICS / Carmen Mangion on Sr Mary Clare Moore Born in Dublin To mark our anniversary, we have invited 50 Catholics to choose adored. In October 1854 she led on 20 March a person from the past 175 years whose life has been a personal a party of four Bermondsey sisters 1814, Georgiana inspiration to them and an example of their faith at its best to join Nightingale to nurse in the Moore converted Crimea. Jerry Barrett’s painting to Catholicism the first four women to join her, the leaders that founded nine Mission of Mercy: Florence with her mother taking the name Mary Clare. Convents of Mercy in England. Nightingale receiving the wounded in 1823. Aged Aged 23, Moore became supe- She worked well with the at Scutari (in the National Portrait 14, she was rior of the Cork convent. Then in English hierarchy, becoming a Gallery) gives us our only contem- employed by the founder of the 1839, she was lent to the first close and trusted confidante of porary image of her. Her face, like Sisters of Mercy, Catherine English foundation in the slums Thomas Grant, the Bishop of her life, is in the shadows. McAuley, as a governess but was of Bermondsey, south London. Southwark. Her letters to her sis- Mary Clare Moore died of soon drawn by her House of She managed the Convent of ters reflect her compassion and pleurisy in 1874, aged only 60, Mercy, a refuge and school for Mercy in Bermondsey until her encouragement. She wrote to con- but worn out by her exertions on impoverished female servants death in 1874. -

Jesus Christ's Sufferings and Death in the Iconography of the East and the West

Скрижали, 4, 2012, с. 122-138 V.V.Akimov Jesus Christ's sufferings and death in the iconography of the East and the West The image of God sufferings, Jesus Christ crucifixion has received such wide spreading in the Christian world that is hardly possible to count up total of the similar monuments created throughout last one and a half thousand of years. The crucifixion has got a habitual symbol of Christianity and various types of the Crucifix became a distinctive feature of some Christian faiths. From time to time modern Christians, looking at the Cross with crucified Jesus Christ, don’t think of the tragedy of Christ’s death and the joy of His resurrection but whether the given Crucifix is «their own» or «another's». Meanwhile, the iconography of the Crucifix as far as the iconography of God’s Mother can testify to a generality of Christian tradition of the East and the West. There are much more general lines than differences between them. The evangelical narration of God sufferings and the history of Crucifix iconography formation, both of these, testify to the unity of east and western tradition of the image of the Crucifixion. Traditions of the East and the West had one source and were in constant interaction. Considering the Crucifix iconography of the East and the West in a context of the evangelical narration and in a historical context testifies to the unity of these traditions and leads not to dissociation, conflicts and mutual recriminations, but gives an impulse to search of the lost unity. -

J?, ///? Minor Professor

THE PAPAL AGGRESSION! CREATION OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND, 1850 APPROVED! Major professor ^ J?, ///? Minor Professor ItfCp&ctor of the Departflfejalf of History Dean"of the Graduate School THE PAPAL AGGRESSION 8 CREATION OP THE SOMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND, 1850 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For she Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Denis George Paz, B. A, Denton, Texas January, 1969 PREFACE Pope Plus IX, on September 29» 1850, published the letters apostolic Universalis Sccleslae. creating a terri- torial hierarchy for English Roman Catholics. For the first time since 1559» bishops obedient to Rome ruled over dioceses styled after English place names rather than over districts named for points of the compass# and bore titles derived from their sees rather than from extinct Levantine cities« The decree meant, moreover, that6 in the Vati- k can s opinionc England had ceased to be a missionary area and was ready to take its place as a full member of the Roman Catholic communion. When news of the hierarchy reached London in the mid- dle of October, Englishmen protested against it with unexpected zeal. Irate protestants held public meetings to condemn the new prelates» newspapers cried for penal legislation* and the prime minister, hoping to strengthen his position, issued a public letter in which he charac- terized the letters apostolic as an "insolent and insidious"1 attack on the queen's prerogative to appoint bishops„ In 1851» Parliament, despite the determined op- position of a few Catholic and Peellte members, enacted the Ecclesiastical Titles Act, which imposed a ilOO fine on any bishop who used an unauthorized territorial title, ill and permitted oommon informers to sue a prelate alleged to have violated the act.