Byzantine Gastronomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùù

ùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùùù K. S. Sorochan Byzantine Spices as a Daily Byzantine Cuisine Part picery, preservatives and seasonings were widely used in the daily cuisine of Byzantine Empire, succeeded the traditions of ancient Greece and Rome. They were in the list of the main components of the diet of a Middle Byzantium. But due to change of territorial boundaries, contact with new peoples and development of intercon- tinental trade service the assortment of Roman τὰ ἀρώματα (τὸ ἄρωμα — aromatic herb, spice), and the forms of their use have been rather changed. Therefore, it is necessary to clarify the range of this goods, direction and terminal points of its import-export trade movements, to find out the issue on professional specialization of trade in spicery, which were ap- preciated and really valuable. At that the spices popularity had not been decreased as they were in the same demand as the preservatives for their special ability to inhibit bacteria (bactericidal action), mainly putrefaction bacteria, and so to promote continued preservation of food. Byzantine historiography of the issue is rather narrow. Usually the researches study spe- cies in the context of Byzantine Empire’s cuisine or perfumery (Ph. Koukoules, M. Grünbart, J. Koder, A. Dalby and especially I. Anagnostakis), or less — Roman trade (J. Irmscher, A. Laiou, N. Oikonomides, С. Morrisson). The works of M. Montanari relate more to me- dieval Italy and Western Europe culinary tradition, but also contain some references to Byz- antium in context of trade relationship [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. There are studies of this kind applied to the history of ancient Greece and Rome such as works of J. -

In Ancient and Early Byzantine Medicine and Cuisine

MEDICINA NEI SECOLI ARTE E SCIENZA, 30/2 (2018) 579-616 Journal of History of Medicine Articoli/Articles MALABATHRON (ΜΑΛΑΒΑΘΡΟΝ) IN ANCIENT AND EARLY BYZANTINE MEDICINE AND CUISINE MACIEJ KOKOSZKO ZOFIA RZEŹNICKA Department of Byzantine History, University of Łódź, Łódź, PL The Waldemar Ceran Research Centre for the History and Culture of the Mediterranean Area and South-East Europe Ceraneum, University of Łódź, Łódź, PL SUMMARY This study of the history and applications of μαλάβαθρον (malábathron), known as tejpat, suggests that the spice had an appreciable effect on Mediterranean medicine and cuisine. A significant increase in the interest in the plant occurred in the 1st c. BC, though extant information on the dietetic-pharmacological uses of tejpat dates only to the 1st c. AD, and appears in Dioscorides’ De materia medica. Malábathron never became a common medicament, nor a cheap culinary ingredient. Nevertheless, it was regularly used in medical practice, but only in remedies prescribed to the upper social classes. In Roman cuisine it was also an ingredient of sophisticated dishes. In De re coquinaria it features in twelve preparations. Sources Any research into the role of μαλάβαθρον (malábathron – tejpat in English) in antiquity and the early Middle Ages has to be based on a wide range of sources. Only sources of primary importance, how- Key words: History of medicine - History of food - Tejpat, spices 579 Maciej Kokoszko, Zofia Rzeźnicka ever, are listed and briefly here. Three texts of the 1st c. AD should definitely be mentioned for the study of the provenance and origins of tejpat’s presence in the Mediterranean: the anonymous Periplus Maris Erythraei1, Historia naturalis by Pliny the Elder2, and De ma- teria medica by Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbus3. -

Chapter 3 the Social and Economic History of the Cyclades

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/58774 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Roussos, K. Title: Reconstructing the settled landscape of the Cyclades : the islands of Paros and Naxos during the late antique and early Byzantine centuries Issue Date: 2017-10-12 Chapter 3 The social and economic history of the Cyclades 3.1 INTRODUCTION in the early 13th century (the domination of the Franks on the Aegean islands and other Byzantine The Cyclades are rarely mentioned in the territories) shaped the historical fate of the islands of literary sources of Late Antiquity and the Byzantine the southern Aegean and the Cyclades in particular. Early Middle Ages. Sporadic information in different The chronological framework followed by this kind of written sources that are separated by a study is: i) the Late Antique or Late Roman period great chronological distance, such as the Hierokles (from the foundation of Constantinople in 324 to the Synekdemos (Parthey 1967; see more in Chapter middle 7th century), ii) the Byzantine Early Middle 3.3.2), the Stadiasmus of Maris Magni (Müller 1855; Ages or the so-called “Byzantine Dark centuries” see more in Chapter 5.2.2), Notitiae Episcopatuum, (from the late 7th to the early 10th century), and iii) Conciliar Acts (Mansi 1961; Darrouzès 1981; the Middle Byzantine period (from the middle 10th Fedalto 1988; see more in Chapters 3.3.3 and 3.), century to the beginning of the venetian occupation hagiographical texts (the Life of Saint Theoktiste: in 1207). This chronological arrangement slightly Talbot 1996; see more in Chapter 1.3; the Miracles differs from the general historical subdivision of of Saint Demetrius: Lemerle 1979; 1981; Bakirtzes the Byzantine Empire, because it is adjusted to the 1997; see more in Chapter 3.3.2), the lists of the civil, peculiar circumstances pertaining to the maritime military and ecclesiastical offices of the Byzantine area of the south Aegean after the 7th century. -

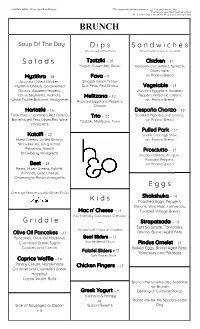

Menu Items Also Available

11:00PM-4:00PM | Weekends & Bank Holidays *The consumption of raw or uncooked eggs, meat, poultry or shellfish may increase your risk of food borne illness. Please inform your server of any allergies or dietary restrictions. BRUNCH Soup Of The Day D i p s S a n d w i c h e s Served with Pita Points Served with Crisps or Crudités Tzatziki – 10 – 17 S a l a d s Chicken Yogurt, Cucumber, Garlic Haloumi, Cucumbers, Spinach, Olive Paste, Myzithra – 18 Fava – 9 on Panino Bread Arugula, Grilled Chicken, Smooth Greek Yellow Myzithra Cheese, Caramelized Split Peas, Red Onions Vegetable – 13 Onions, Roasted Peppers, Zucchini, Eggplant, Roasted Citrus Segments, Walnuts, Melitzana – 13 Peppers, Balsamic Cream, White Truffle Balsamic Vinaigrette Roasted Eggplant, Peppers, on Panino Bread Onions Horiatiki – 16 Despaña Chorizo – 15 Tomatoes, Cucumbers,Red Onions, Trio – 22 Sautéed Peppers and Onions, Barrel-Aged Feta,Olives,Red Wine Tzatziki, Melitzana, Fava on Panino Bread Vinaigrette Pulled Pork – 17 Kataïfi – 22 Greek Cabbage Slaw, Mixed Greens, Grilled Shrimp, on Panino Bread Strawberries, Gorgonzola, Pistachios, Kataïfi, Prosciutto – 17 Strawberry Vinaigrette Kasseri Cheese, Arugula, Roasted Peppers, Beet – 18 on Panino Bread Beets, Mixed Greens, Falafel, Almonds, Goat Cheese, Champagne Raisin Vinaigrette E g g s Dressings Feature Locally-Owned EVOO Shakshuka – 14 K i d s Poached Eggs, Peppers, Onions, Vine Ripe Tomatoes, Mac n’ Cheese – 11 Toasted Village Bread Kid Friendly Cavatappi Cheddar G r i d d l e — Strapatsada – 13 Soft Scramble, Tomatoes, -

Traditional Foods in Europe- Synthesis Report No 6. Eurofir

This work was completed on behalf of the European Food Information Resource (EuroFIR) Consortium and funded under the EU 6th Framework Synthesis report No 6: Food Quality and Safety thematic priority. Traditional Foods Contract FOOD – CT – 2005-513944. in Europe Dr. Elisabeth Weichselbaum and Bridget Benelam British Nutrition Foundation Dr. Helena Soares Costa National Institute of Health (INSA), Portugal Synthesis Report No 6 Traditional Foods in Europe Dr. Elisabeth Weichselbaum and Bridget Benelam British Nutrition Foundation Dr. Helena Soares Costa National Institute of Health (INSA), Portugal This work was completed on behalf of the European Food Information Resource (EuroFIR) Consortium and funded under the EU 6th Framework Food Quality and Safety thematic priority. Contract FOOD-CT-2005-513944. Traditional Foods in Europe Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 What are traditional foods? 4 3 Consumer perception of traditional foods 7 4 Traditional foods across Europe 9 Austria/Österreich 14 Belgium/België/Belgique 17 Bulgaria/БЪЛГАРИЯ 21 Denmark/Danmark 24 Germany/Deutschland 27 Greece/Ελλάδα 30 Iceland/Ísland 33 Italy/Italia 37 Lithuania/Lietuva 41 Poland/Polska 44 Portugal/Portugal 47 Spain/España 51 Turkey/Türkiye 54 5 Why include traditional foods in European food composition databases? 59 6 Health aspects of traditional foods 60 7 Open borders in nutrition habits? 62 8 Traditional foods within the EuroFIR network 64 References 67 Annex 1 ‘Definitions of traditional foods and products’ 71 1 Traditional Foods in Europe 1. Introduction Traditions are customs or beliefs taught by one generation to the next, often by word of mouth, and they play an important role in cultural identification. -

The Food and Culture Around the World Handbook

The Food and Culture Around the World Handbook Helen C. Brittin Professor Emeritus Texas Tech University, Lubbock Prentice Hall Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montreal Toronto Delhi Mexico City Sao Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo Editor in Chief: Vernon Anthony Acquisitions Editor: William Lawrensen Editorial Assistant: Lara Dimmick Director of Marketing: David Gesell Senior Marketing Coordinator: Alicia Wozniak Campaign Marketing Manager: Leigh Ann Sims Curriculum Marketing Manager: Thomas Hayward Marketing Assistant: Les Roberts Senior Managing Editor: Alexandrina Benedicto Wolf Project Manager: Wanda Rockwell Senior Operations Supervisor: Pat Tonneman Creative Director: Jayne Conte Cover Art: iStockphoto Full-Service Project Management: Integra Software Services, Ltd. Composition: Integra Software Services, Ltd. Cover Printer/Binder: Courier Companies,Inc. Text Font: 9.5/11 Garamond Credits and acknowledgments borrowed from other sources and reproduced, with permission, in this textbook appear on appropriate page within text. Copyright © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 07458. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. This publication is protected by Copyright, and permission should be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, or transmission in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or likewise. To obtain permission(s) to use material from this work, please submit a written request to Pearson Education, Inc., Permissions Department, 1 Lake Street, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 07458. Many of the designations by manufacturers and seller to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. -

Cretan Dinner

CRETAN DINNER STARTERS SALADS Chicken Soup Spinach 10,00€ 14,00€ With coarsely cooked tomatoes in the wood Hearts of spinach arugula, pomegranate, oven and pure virgin olive oil. crushed sour mizithra, almond, jelly from strawberry and orange fillets with pumpkin seeds. Flute 10,00€ Potato salad With greens and fennel on cream cheesse. 15,00€ Salad of broken boiled potatoes, summer toma- Liver toes, cucumber, onion and egg with 14,00€ pure virgin olive oil and village vinegar. Savory liver with caramelized onions & raisins. Snails 11,00€ PASTA With coarse salt, rosemary and vinegar. Skioufichta Haniotiko mpoureki 14,00€ 12,00€ Cretan traditional pasta cooked with tomato, Zucchini and Potato pie from Chania. served with cream cheese. Zucchini blossoms Magiri 13,00€ 16,00€ Stuffed with wild artichokes vegetables, rice and Round shapped Cretan pasta, with rabbit, light yoghurt mousse. and dry cream cheese. Meatballs Pilaf 12,00€ 14,00€ Minced beef with sour & mint served with With smoked apaki lime and saffron. smoked paprika emulsion. Cretan Tacos 12,00€ With lightly cooked lamb and potato. MAIN COURSES DESSERTS Organic Chicken Baklava 18,00€ 11,00€ Stuffed with Cretan gruyere, sun-dried tomatoes With walnuts and fresh vanilla ice cream with and olives on spinach & cream. cinnamon. Beef Sfakiani pie 19,00€ 11,00€ Roasted in dessert wine and round maggiri Traditional pie from Sfakia, stuffed with sweet with gruyere & okra. mizithra served with honey. Lamb shank Cool pie 22,00€ 11,00€ Simmered in the wood oven with herbs and With sheep yoghurt and sour cherries. papardelles cooked in its own juice with tomato and Cretan cream cheese. -

|||GET||| a Short History of Byzantium 1St Edition

A SHORT HISTORY OF BYZANTIUM 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE John Julius Norwich | 9780679772699 | | | | | Byzantine Chronicle Preface xxxvi. Although Norwich does his best to keep the pace brisk and lively, the book still A Short History of Byzantium 1st edition like it drags on a bit, particularly towards the end. And when they weren't having those Wow they sure did a lot of gouging out of eyes and tongues and noses and throwing people off cliffs! Norwich's page narrative of the year history of the Normans Kingd This is a truly ghastly book by an historian who has written several outstanding works. Picture Information. Leo was also the first emperor to receive the crown not from a general or A Short History of Byzantium 1st edition officer, as in the Roman tradition, but from the hands of the patriarch of Constantinople. As for bread, the bakers of Constantinople were in a most favored trade, according to the ninth century Book of the Eparch, a handbook of city administration: "bakers are never liable to be called for any public service, neither themselves nor their animals, to prevent any interruption of the baking of bread. It had seen the birth of a new capital, and the adoption of Christianity as the official religion of the Empire. The Vandals surrendered after a couple of battles, and Belisarius returned to a Roman triumph in Constantinople with the last Vandal king, Gelimer, as his prisoner. Jun 28, Jared rated it it was amazing. The Donation of Constantine, one of the most famous forged documents in history, played a crucial role in this. -

Liudprand Von Cremona Als Gesandter Am Byzantinischen Kaiserhof*

Johannes Koder Erfolglos als Diplomat, erfolgreich als Erzähler? Liudprand von Cremona als Gesandter am byzantinischen Kaiserhof* Vorbemerkungen ner Porphyrogenita nicht, sondern sandte Theophano, eine Nichte des Nikephoros Phokas 4 . Die Vermählung fand am 14. Liudprand von Cremona 1 (im Folgenden L.) wurde bald nach April 972 in Rom statt. L. starb 971 oder 972, während der 920 geboren 2 und genoss eine vorzügliche Ausbildung an der Reise oder wenig später. Rhetorikschule in Pavia. Nach seinen Studien wurde er, um Vorweg sei auf einige Besonderheiten der Antapodosis 940, in Pavia zum Diakon (levites Ticinensis) geweiht. Ab der und der Relatio hingewiesen. Auffallend ist die fallweise bis Jahreswende wirkte er in dem ca. 90 km entfernten Cremona ins Detail gehende Genauigkeit seiner Schilderungen. Die- als Bischof. ser Genauigkeit der Berichterstattung steht eine beachtliche L. hielt sich wahrscheinlich dreimal in Kon stan tinopel auf: Flexibilität der Interpretation vergleichbarer Geschehnisse ge- Das erste Mal wurde er im Herbst 949 von Berengar II. von genüber, die in der – jeweils situationsbedingt unterschiedli- Ivrea (900-966, Markgraf seit ca. 925, von 950 bis 961 Kö- chen – positiven oder negativen Schilderung zum Ausdruck nig von Italien) zu Kaiser Kon stan tin VII. Porphyrogennetos kommt. Zwei Beispiele, die über die jeweiligen konkreten entsandt. Über diesen ersten Aufenthalt in Kon stan tinopel Situationen hinaus auch einen hohen Symbolwert haben: Das berichtet er im »Buch der Vergeltung der Könige und Fürsten kaiserliche Zeremoniell wird in Antapodosis VI stets positiv eines Teils von Europa« (Liber Antapodóseos, Aνταποδοσεως, kommentiert, in der Relatio hingegen stets negativ 5 . Dies trifft retributionis, regum atque principum partis Europae, im Fol- auch für die feierliche kaiserliche Tafel und die aus diesem genden: Antapodosis). -

Cathedral President Reveals Multiple Problems Catsimatidis Comes Close

S O C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of E ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek- Americans N c v A wEEkly GREEk-AmERICAN PuBlICATION www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 16, ISSUE 831 September 14-20, 2013 $1.50 Catsimatidis Comes Dukakis: Punish the Users of Chemical Weapons Close; Constantinides Ex-Pres. Candidate Talks to TNH about Wins by a Landslide Syria, Debt, Greece By Constantine S. Sirigos over this two opponents, each By Theodore Kalmoukos of who gained about 22 percent. NEW YORK – In a mixed night He is now well-positioned to be - BOSTON, MA – A quarter cen - for Greek-American candidates come the first Greek- or Cypriot- tury ago, then-Massachusetts in New York City politics, may - American – he has roots in both Governor Michael Dukakis was oral hopeful John Catsimatidis countries – to be elected to the the Democratic Party’s nominee mounted a strong challenge to City Council. for president of the United Joe Lhota, capturing approxi - The throng that filled the States. After leading his Repub - mately 41 percent of the Repub - ballroom of Manhattan’s Roo - lican opponent – George H.W. lican Primary, with Lhota win - sevelt hotel came to terms with Bush, who was Vice President ning with about 52. Although the numbers on the big screen under President Ronald Reagan Catsimatidis was endorsed by long before John and Margo at the time – in the polls the Liberal Party a few months Catsimatidis made their en - through the summer of 1988, ago, it remained unclear at press trance, but they were in an exu - Dukakis lost his lead by the fall time whether he would stay in berant mood nonetheless. -

Pics for PECS 2011 Wordlist

Pics for PECS™ 2011 Wordlist© new images are in red Alphabet and Numerals Upper case A-Z Lower case a-z Numerals 0-10 Activities and Events 1. art 1 30. empty trash 59. morning circle 91. sort mail 2. art 2 31. file 2 92. sort post 3. assembly 32. fingerpaint 60. mow lawn 93. sort silverware 4. bed time 33. fire drill 1 61. music 94. sort washing 5. breakfast 34. fire drill 2 62. music class 95. sorting 6. cafeteria 35. fold 63. OT 96. speech 7. centers 36. fold clothes 64. party 97. spelling 8. centres 37. food prep 65. PE 1 98. stock shelves 9. change 38. grooming 66. PE 2 99. story time clothes 39. gross motor 67. picnic 100. stuff 10. circle 2 40. gross motor 68. play area envelopes 11. circle 3 game 69. PT 101. surprise 12. class 41. group 70. quiet time 102. sweep 13. clean 42. gym 71. reading 103. take out bathroom 43. iron 72. recess rubbish 14. collate 44. jobs 73. rec-leisure 104. take out trash 15. color 45. laminate 74. recycle 105. vacuum 16. colour 46. leisure 75. rice table 106. vending 17. cook 47. library 76. sand pit machine 18. cooking 48. line up 77. sand play 107. walk the dog 19. crafts 49. listen 78. sand table 108. wash dishes 20. cut grass 50. listening 79. sand tray 109. wash face 21. deliver mail 51. load 80. sandbox 110. wash hands 22. deliver dishwasher 81. school shop 111. wash windows message 52. look out 82. -

0 Koder Bibliographie 01

Schriftenverzeichnis Johannes Koder http://tib.oeaw.ac.at/repository/Bibliographie_Koder.pdf Monographien / Sammelbände 1 Die Hymnen Symeons des neuen Theologen. Vorarbeiten zu einer kritischen Ausgabe, maschinschriftl. Diss., Wien 1965, 128 S. 2 Syméon le nouveau théologien, Hymnes, t. I, Introduction, texte critique et notes (traduction par J. Paramelle) 301 S., t. II, Texte (traduction et notes par L. Neyrand) 499 S., t. III, Texte et index (Traduction et notes par J. Paramelle et L. Neyrand) 402 S. (Sources Chrétiennes 156, 174, 196), Paris 1969, 1971, 1973. 3 Negroponte. Untersuchungen zur Topographie und Siedlungsgeschichte der Insel Euboia während der Zeit der Venezianerherrschaft, Wien 1973 (VTIB 1 = Denkschr. ph. h. Kl. ÖAW 112), 191 S., 76 Abb., 16 Textfig. 4 (unter Mitarbeit von F. Hild) (Register von P. Soustal) Tabula Imperii Byzantini 1: Hellas und Thessalia (Denkschr. ph. h. Kl. ÖAW 125), Wien 1976, 316 S. mit 2 Karten. 5 Friedrich Rückert und Byzanz. Der Gedichtzyklus „Hellenis“ und seine byzantinischen Quellenvorlagen, Schweinfurt 1982 (Rückert-Studien IV), 1-117. 6 Der Lebensraum der Byzantiner. Historisch-geographischer Abriß ihres mittelalterlichen Staates im östlichen Mittelmeerraum (Byz. Gesch.-schreiber, Erg. bd. 1), Graz-Wien-Köln 1984, 190 S., 23 Abb., 1 Faltkarte. Nachdruck mit bibliographischen Nachträgen, Wien 2001, 222 S., 23 Abb., 1 Faltkarte. 7 Das Eparchenbuch Leons des Weisen, Einführung, Edition, Übersetzung und Indizes (Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae XXXIII). Wien 1991, 168 S., 10 Taf. 8 Gemüse in Byzanz. Die Frischgemüseversorgung Konstantinopels im Licht der Geoponika (Byz. Geschichtsschreiber, Erg.band 3), Wien, Fassbaender 1993, 131 S., 3 Fig. 9 Mit der Seele Augen sah er deines Lichtes Zeichen, Herr ..