The Shi of Huizhou Merchants and Craftsmen Around 1800 AD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater Bay Area Logistics Markets and Opportunities Colliers Radar Logistics | Industrial Services | South China | 29 May 2020

COLLIERS RADAR LOGISTICS | INDUSTRIAL SERVICES | SOUTH CHINA | 29 MAY 2020 Rosanna Tang Head of Research | Hong Kong SAR and Southern China +852 2822 0514 [email protected] Jay Zhong Senior Analyst | Research | Guangzhou +86 20 3819 3851 [email protected] Yifan Yu Assistant Manager | Research | Shenzhen +86 755 8825 8668 [email protected] Justin Yi Senior Analyst | Research | Shenzhen +86 755 8825 8600 [email protected] GREATER BAY AREA LOGISTICS MARKETS AND OPPORTUNITIES COLLIERS RADAR LOGISTICS | INDUSTRIAL SERVICES | SOUTH CHINA | 29 MAY 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INSIGHTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 3 MAP OF GBA LOGISTICS MARKETS AND RECOMMENDED CITIES 4 MAP OF GBA TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM 5 LOGISTICS INDUSTRY SUPPLY AND DEMAND 6 NEW GROWTH POTENTIAL AREA IN GBA LOGISTICS 7 GBA LOGISTICS CLUSTER – ZHUHAI-ZHONGSHAN-JIANGMEN 8 GBA LOGISTICS CLUSTER – SHENZHEN-DONGGUAN-HUIZHOU 10 GBA LOGISTICS CLUSTER – GUANGZHOU-FOSHAN-ZHAOQING 12 2 COLLIERS RADAR LOGISTICS | INDUSTRIAL SERVICES | SOUTH CHINA | 29 MAY 2020 Insights & Recommendations RECOMMENDED CITIES This report identifies three logistics Zhuhai Zhongshan Jiangmen clusters from the mainland Greater Bay The Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau We expect Zhongshan will be The manufacturing sector is Area (GBA)* cities and among these Bridge Zhuhai strengthens the a logistics hub with the now the largest contributor clusters highlights five recommended marine and logistics completion of the Shenzhen- to Jiangmen’s overall GDP. logistics cities for occupiers and investors. integration with Hong Kong Zhongshan Bridge, planned The government aims to build the city into a coastal logistics Zhuhai-Zhongshan-Jiangmen: and Macau. for 2024, connecting the east and west banks of the Peral center and West Guangdong’s > Zhuhai-Zhongshan-Jiangmen’s existing River. -

Study on the Measurement of Regional Economic Connection in the Pearl River Delta

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 416 4th International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2020) Study on the Measurement of Regional Economic Connection in the Pearl River Delta Longfang Chen Zhuhai College of Jilin University Zhuhai, China 519041 Abstract—The process of regional economic development is agricultural products, and in technology and economy. [1] a process in which regional economic connections are The measures include accessibility, economic influence continuously strengthened. This paper uses gravity model to scope, economic connection strength, the degree of measure the economic connection strength and total strength economic membership, and so on. The measurement models of cities in the Pearl River Delta from 2000 to 2017, and then mainly include gravity model, central function intensity calculates the economic connection strength within the region, model, and potential model. Many scholars in academia have and analyzes the historical trajectory of economic connections used various methods to measure and study the regional in the Pearl River Delta. The results show that the total economic connections in the economic zone on the west side strength of economic connections between the cities in the of the Straits, the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban Pearl River Delta keeps going up, forming the Guangzhou- agglomeration, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Pearl River Foshan-Shenzhen area with the strongest total strength of connections, Dongguan-Zhongshan-Jiangmen area with strong Delta [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]. Regarding the study of regional total strength and Huizhou-Zhuhai-Zhaoqing area with weak economic connection in the Pearl River Delta, Zhu Lie total strength. -

Huizhou Is Envisioned As Guangdong Silicon Valley

News Focus No.3 2019 Huizhou is envisioned as PEGGY CHEUNG ADVISORY DEPARTMENT Guangdong Silicon Valley JAPANESE CORPORATE BANKING DIVISION FOR ASIA T +852-2821-3782 [email protected] MUFG Bank, Ltd. 20 FEB 2019 A member of MUFG, a global financial group When talking about China Silicon Valley or Innovation Hub, the first place that comes to mind would be the media darling-Shenzhen. Following in Shenzhen’s footsteps, the wave of innovation has not only been set off in its neighbouring cities such as Guangzhou and Dongguan, but also in Huizhou, where the local government is putting effort in building Guangdong Silicon Valley. This article will give a brief introduction on Huizhou’s movement towards establishment of Guangdong Silicon Valley and its current Social Implementation1 of innovation and advanced technology. 1. BACKGROUND Huizhou occupies a pivotal position in Shenzhen-Dongguan-Huizhou Economic Circle2 and lies in the core district of eastern Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (hereinafter “Greater Bay Area”). Since China’s reform and opening up, it has been acting as one of the major industrial cities in Pearl River Delta (hereinafter “PRD”) and has matured petrochemicals and electronic information industries as its pillar industries. Apart from undertaking overflowed industries from Shenzhen and Dongguan, over recent years, Huizhou has been accelerating its level of high-tech R&D activity, with the ultimate goal of evolving as an innovation hub for the emerging industries in Guangdong province. Huizhou was designated -

The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China

The Heritage of Non-theistic Belief in China Joseph A. Adler Kenyon College Presented to the international conference, "Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought" (San Diego, September 2011) Naturalism and humanism have long histories in China, side-by-side with a long history of theistic belief. In this paper I will first sketch the early naturalistic and humanistic traditions in Chinese thought. I will then focus on the synthesis of these perspectives in Neo-Confucian religious thought. I will argue that these forms of non-theistic belief should be considered aspects of Chinese religion, not a separate realm of philosophy. Confucianism, in other words, is a fully religious humanism, not a "secular humanism." The religion of China has traditionally been characterized as having three major strands, the "three religions" (literally "three teachings" or san jiao) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Buddhism, of course, originated in India in the 5th century BCE and first began to take root in China in the 1st century CE, so in terms of early Chinese thought it is something of a latecomer. Confucianism and Daoism began to take shape between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. But these traditions developed in the context of Chinese "popular religion" (also called folk religion or local religion), which may be considered a fourth strand of Chinese religion. And until the early 20th century there was yet a fifth: state religion, or the "state cult," which had close relations very early with both Daoism and Confucianism, but after the 2nd century BCE became associated primarily (but loosely) with Confucianism. -

Impacts of Urbanization on the Ecosystem Services in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, China

remote sensing Article Impacts of Urbanization on the Ecosystem Services in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, China Xuege Wang 1,2,3, Fengqin Yan 2 and Fenzhen Su 1,2,3,* 1 School of Geography and Ocean Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China; [email protected] 2 State Key Laboratory of Resources and Environmental Information System, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] 3 Collaborative Innovation Center for the South China Sea Studies, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 September 2020; Accepted: 6 October 2020; Published: 8 October 2020 Abstract: Unprecedented urbanization has occurred globally, which has converted substantial natural landscapes into impervious surfaces and further impacted ecosystem services and functioning. In this study, we quantified the spatiotemporal patterns of urbanization and investigated the impacts of urbanization on the ecosystem service value (ESV) in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) of China from 1980 to 2018. The results show that the GBA has experienced extensive urbanization, with the urban area increasing from 2607.4 to 8243.5 km2 from 1980 to 2018. Zhongshan, Zhuhai, Dongguan, Shenzhen, and Foshan exhibited the top five highest urban expansion rates. Throughout the study period, edge expansion was the most dominant growth mode, with a decreasing trend, while infilling increased in the GBA. The total ESV loss induced by urban expansion in the GBA reached 40.5 billion yuan over the past four decades. The ESV loss due to the water body decrease caused by urbanization was the largest. -

A Abbasid Caliphate, 239 Relations Between Tang Dynasty China And

INDEX A anti-communist forces, 2 Abbasid Caliphate, 239 Antony, Robert, 200 relations between Tang Dynasty “Apollonian” culture, 355 China and, 240 archaeological research in Southeast Yang Liangyao’s embassy to, Asia, 43, 44, 70 242–43, 261 aromatic resins, 233 Zhenyuan era (785–805), 242, aromatic timbers, 230 256 Arrayed Tales aboriginal settlements, 175–76 (The Arrayed Tales of Collected Abramson, Marc, 81 Oddities from South of the Abu Luoba ( · ), 239 Passes Lĩnh Nam chích quái liệt aconite, 284 truyện), 161–62 Agai ( ), Princess, 269, 286 becoming traditions, 183–88 Age of Exploration, 360–61 categorizing stories, 163 agricultural migrations, 325 fox essence in, 173–74 Amarapura Guanyin Temple, 314n58 and history, 165–70 An Dương Vương (also importance of, 164–65 known as Thục Phán ), 50, othering savages, 170–79 165, 167 promotion of, 164–65 Angkor, 61, 62 savage tales, 179–83 Cham naval attack on, 153 stories in, 162–63 Angkor Wat, 151 versions of, 170 carvings in, 153 writing style, 164 Anglo-Burmese War, 294 Atwill, David, 327 Annan tuzhi [Treatise and Âu Lạc Maps of Annan], 205 kingdom, 49–51 anti-colonial movements, 2 polity, 50 371 15 ImperialChinaIndexIT.indd 371 3/7/15 11:53 am 372 Index B Biography of Hua Guan Suo (Hua Bạch Đằng River, 204 Guan Suo zhuan ), 317 Bà Lộ Savages (Bà Lộ man ), black clothing, 95 177–79 Blakeley, Barry B., 347 Ba Min tongzhi , 118, bLo sbyong glegs bam (The Book of 121–22 Mind Training), 283 baneful spirits, in medieval China, Blumea balsamifera, 216, 220 143 boat competitions, 144 Banteay Chhmar carvings, 151, 153 in southern Chinese local Baoqing siming zhi , traditions, 149 224–25, 231 boat racing, 155, 156. -

Millet, Wheat, and Society in North China in the Very Long Term By

Cereals and Societies: Millet, Wheat, and Society in North China in the Very Long Term By Hongzhong He, Joseph Lawson, Martin Bell, and Fuping Hui. Abstract: This paper outlines a very longue durée history of three of North China’s most important cereal crops—broomcorn and foxtail millet, and wheat—to illustrate their place within broader social-environmental formations, to illustrate the various biological and cultural factors that enable the spread of these crops, and the ways in which these crops and the patterns in which they are grown influenced the further development of the societies that grew them. This article aims to demonstrate that a very long-run approach raises new questions and clarifies the significance of particular transitions. It, firstly, charts the transition from broomcorn to foxtail millet cultivation in the late Neolithic; secondly, shows efforts to spread winter wheat often met some degree of resistance from farming communities; thirdly, considers the significance of the different processing requirements of wheat and millet, and their implications for social and economic development; and, fourthly, considers the debate over the spread of multiple-cropping systems to North China. Introduction Scholars have highlighted the importance of crops in comparative studies that seek to explain broad differences in development among various Eurasian societies over long periods of time.1 European crops—oats, barley, wheat, and rye—entailed the proliferation of mills, establishing the monasteries and magnates who owned them, and rudimentary mechanization, at the heart of European society. In contrast, the East Asian rice growing communities invested not in milling-machines, but in skilled labour. -

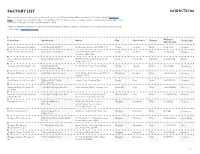

Factory List

FACTORY LIST Our commitment to transparency is core to our Corporate Social Responsibility efforts. Nordstrom’s Tier 1 factory list for Nordstrom Made, our family of private-label brands, is included below. This list reflects our most strategic suppliers, which we classify internally as Level 1 and Level 2. The data is current as of December 11, 2020. Additional information about our commitment to human rights, including our goals for ethical labor practices and women’s empowerment, can be found on nordstromcares.com. Factory Name Manufacturer Address City State/Province Country Employees Product Type (Male/Female) Industria de Calcados Karlitos Ltda. South Service Trading S/A Rua Benedito Merlino, 999, 14405-448 Franca Sao Paulo Brazil 146 (62/84) Footwear Industria de Calcados Kissol Ltda. South Service Trading S/A Rua Irmãos Antunes, 813, Jardim Franca Sao Paulo Brazil 196 (137/59) Footwear Guanabara, 14405-445 Eminent Garment (Cambodia) Eminent Garment Limited Phum Preak Thmey, Khum Teukvil, Srok Saang Khet Kandal Cambodia 866 (105/761) Woven Limited Saang, Phnom Penh Zhejiang Sunmans Knitting Co. Ltd. Royal Bermuda LLC No. 139 North of Biyun Road, 314400 Haining Zhejiang China 197 (39/158) Accessories West Coast Hosiery Group Dongguan Mayflower Footwear Corp. Pagoda International Footwear Golden Dragon Road, 1st Industrial Park of Dongcheng Dongguan China 500 (350/150) Footwear Sangyuan, 523119 Fujian Fuqing Huatai Footwear Co. Madden Intl. Ltd. Trading Lingjiao Village, Shangjing Town Fuqing Fujian China 360 (170/190) Footwear Ltd. Dolce Vita Intl. Nanyuan Knitting & Garments Co. South Asia Knitting Factory Ltd. Nanhua Industry District, Shengxin Town Nanan City Fujian China 604 (152/452) Sweaters Ltd. -

The Ghost of Liaozhai: Pu Songling's Ghostlore and Its History of Reception

THE GHOST OF LIAOZHAI: PU SONGLING’S GHOSTLORE AND ITS HISTORY OF RECEPTION Luo Hui A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Hui Luo, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58980-9 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-58980-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Huizhou Documents a Newl Y Found, Rich And

Zhang Xuehui 5K ~ !, THE HUIZHOU DOCUMENTS A NEWL Y FOUND, RICH AND PRECIOUS SOURCE FOR THE STUDY OF CHINESE HIS TORY Jixi, Shexian, Xiuning, Yixian, Qimen and Wuyuan are six counties located from the southem Anlmi to the northern Jiangxi province. The first five are within the jurisdiction of the modern Anhui Province and the last one, of Jiangxi Province. During Ming and Qing Dynasties in Chinese history, they aB belonged to the Huizhou f*,t 1i'l Prefecture, horne to the renowned scenie spot Huangshan Mountain. Huizhou has been the hometown of many literary figures who played important roles in the development of Chinese culture like Zhu Xi, the founder of Neo-Confucianism, and Hu Shi, the famous modem scholar. Huizhou is now attracting new attention from scholars aB over the world for the diseovery of local documents, whieh cover a span of ab out one thousand years from the Song Dynasty to the 38th year of the Republie of China. The earliest doeument found so far is "Land Sale Contract by Wu Gong in Qimen County in the 8th year of Jiading Reign (1215 AD) in the Song Dynasty" (Songdai Jiading banian Qimen Wu Gong diqi *1~ ~ ;t ;\~~~ n ~A#±1!!.~). The materials in the documents graphicaBy cover not only the six eounties l11entioned above, but also l11any other regions in China as weIl as overseas. There are more than twenty thousand itel11s of Huizhou Doeul11ents eollected l11ainly by the Institute of History and the Institute of Eeonomy of Chinese Aeademy of Social Scienees in Beijing, Animi Province, Nanjing University, Tianjin, and Shandong Provinee. -

Exploring Annual Urban Expansions in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area: Spatiotemporal Features and Driving Factors in 1986–2017

remote sensing Article Exploring Annual Urban Expansions in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area: Spatiotemporal Features and Driving Factors in 1986–2017 Jie Zhang 1,2, Le Yu 3 , Xuecao Li 4 , Chenchen Zhang 1,2, Tiezhu Shi 1,5, Xiangyin Wu 5 , Chao Yang 1 , Wenxiu Gao 5, Qingquan Li 1,2,* and Guofeng Wu 1 1 MNR Key Laboratory for Geo-Environmental Monitoring of Great Bay Area & Guangdong Key Laboratory of Urban Informatics & Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Spatial Smart Sensing and Services, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, China; [email protected] (J.Z.); [email protected] (C.Z.); [email protected] (T.S.); [email protected] (C.Y.); [email protected] (G.W.) 2 College of Civil and Transportation Engineering, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, China 3 Department of Earth System Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China; [email protected] 4 Department of Geological and Atmospheric Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA; [email protected] 5 School of Architecture & Urban Planning, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, China; [email protected] (X.W.); [email protected] (W.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-6485-5094 Received: 13 July 2020; Accepted: 10 August 2020; Published: 13 August 2020 Abstract: The Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macau Greater Bay Area (GBA) of China is one of the largest bay areas in the world. However, the spatiotemporal characteristics and driving mechanisms of urban expansions in this region are poorly understood. Here we used the annual remote sensing images, Geographic Information System (GIS) techniques, and geographical detector method to characterize the spatiotemporal patterns of urban expansion in the GBA and investigate their driving factors during 1986–2017 on regional and city scales. -

Download the Longcheer Fact Sheet

LONGCHEER.COM HONORABLE | PROGRESSIVE | PROFESSIONAL Longcheer, founded in 2002, focuses on the Design, R&D, and Manufacturing of Smart Phones, Tablet/PCs, Virtual Reality THE POWER OF AN and other Smart Products. We provide a complete set of mobile EXPERIENCED PARTNER solutions for product planning, concept design, product delivery, • 17+ years design and and after-sales services. Longcheer aims to be a leading manufacturing experience Smart Products service provider. Our well-developed software, • Full-service ODM specialized hardware, and design capabilities ensure that the company in mid to high volume, multi- continues to meet the diversified needs of our customers. SKU programs As of 2018, Longcheer has sold more than 800 million products. • Quick ramp, high volume Longcheer’s headquarters is located in Shanghai, China and we factory capacity have R&D centers in Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Huizhou. • Modern manufacturing Our manufacturing facilities are located in equipment and technology • Huizhou, Nanchang, Nanning, India, Vietnam and we have Tier 1 supply chain, logistics and quality management business offices in Beijing, • Consistent NPI and Go-to- Shenzhen, Hong Kong, and San Jose, CA (USA). Market processes COMPANY CULTURE • Our Vision: Be a leading smart product service provider • Our Mission: Create values through technology QUALITY • Our Values: Honorable is our principle, Progressive is our CERTIFICATIONS approach and Professional is our execution • ISO 9001: 2015 HOW WE SERVE OUR CUSTOMERS • ISO 14001: 2015 • ISO45001:2018 • QC 080000: 2017 20% CM • ANS/IEC17025:2005 30% JDM • OHSAS 18001: 2007 • ESD CONTROL CERTIFICATION 50% ODM WORLDWIDE PARTNER IN ORIGINAL DESIGN MANUFACTURING 30+ 16,000 5 9.5 MU EXPORT EMPLOYEES MANUFACTURING CAPACITY CHINA LICENSED PRODUCTS FOR EXPORT DEVELOPED 2,650+ FACILITIES PER MONTH AND DOMESTIC ANNUALLY ( ENGINEERS ) ACROSS ALL MARKETS LOCATIONS LONGCHEER.COM HONORABLE | PROGRESSIVE | PROFESSIONAL ORIGINAL DESIGN MANUFACTURING (ODM) Our manufacturing process is enhanced through our broad manufacturing capabilities.