The Organic Intellectual in Filipino Drama 1903-1907

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Patria É Intereses": Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado

3DWULD«LQWHUHVHV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH2ULJLQVDQG &KDQJLQJ0HDQLQJVRI,OXVWUDGR Caroline Sy Hau Philippine Studies, Volume 59, Number 1, March 2011, pp. 3-54 (Article) Published by Ateneo de Manila University DOI: 10.1353/phs.2011.0005 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/phs/summary/v059/59.1.hau.html Access provided by University of Warwick (5 Oct 2014 14:43 GMT) CAROLINE SY Hau “Patria é intereses” 1 Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado Miguel Syjuco’s acclaimed novel Ilustrado (2010) was written not just for an international readership, but also for a Filipino audience. Through an analysis of the historical origins and changing meanings of “ilustrado” in Philippine literary and nationalist discourse, this article looks at the politics of reading and writing that have shaped international and domestic reception of the novel. While the novel seeks to resignify the hitherto class- bound concept of “ilustrado” to include Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs), historical and contemporary usages of the term present conceptual and practical difficulties and challenges that require a new intellectual paradigm for understanding Philippine society. Keywords: rizal • novel • ofw • ilustrado • nationalism PHILIPPINE STUDIES 59, NO. 1 (2011) 3–54 © Ateneo de Manila University iguel Syjuco’s Ilustrado (2010) is arguably the first contemporary novel by a Filipino to have a global presence and impact (fig. 1). Published in America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and in Great Britain by Picador, the novel has garnered rave reviews across Mthe Atlantic and received press coverage in the Commonwealth nations of Australia and Canada (where Syjuco is currently based). -

Emindanao Library an Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition)

eMindanao Library An Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition) Published online by Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, Hawaii July 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii I. Articles/Books 1 II. Bibliographies 236 III. Videos/Images 240 IV. Websites 242 V. Others (Interviews/biographies/dictionaries) 248 PREFACE This project is part of eMindanao Library, an electronic, digitized collection of materials being established by the Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. At present, this annotated bibliography is a work in progress envisioned to be published online in full, with its own internal search mechanism. The list is drawn from web-based resources, mostly articles and a few books that are available or published on the internet. Some of them are born-digital with no known analog equivalent. Later, the bibliography will include printed materials such as books and journal articles, and other textual materials, images and audio-visual items. eMindanao will play host as a depository of such materials in digital form in a dedicated website. Please note that some resources listed here may have links that are “broken” at the time users search for them online. They may have been discontinued for some reason, hence are not accessible any longer. Materials are broadly categorized into the following: Articles/Books Bibliographies Videos/Images Websites, and Others (Interviews/ Biographies/ Dictionaries) Updated: July 25, 2014 Notes: This annotated bibliography has been originally published at http://www.hawaii.edu/cps/emindanao.html, and re-posted at http://www.emindanao.com. All Rights Reserved. For comments and feedbacks, write to: Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa 1890 East-West Road, Moore 416 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Email: [email protected] Phone: (808) 956-6086 Fax: (808) 956-2682 Suggested format for citation of this resource: Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. -

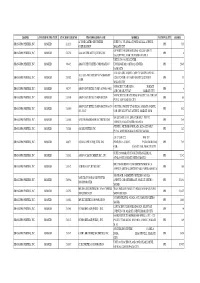

Department of Labor and Employment List of Contractors/Subcontractors Registered Under D.O

Department of Labor and Employment List of Contractors/Subcontractors registered under D.O. 18-A (as of March 2018) Date of Region Name of Establishments Address Registration Number Nature of Business Registration JANITORIAL AND GENERAL IVA @YOURSERVICE MANPOWER AND GENERAL SERVICES, INC. 702A OSMEÑA ST., BRGY. 3, LUCENA CITY, QUEZON 05-Jul-16 ROIVA-QPO-18A-0716-008 SERVICES IX 10 POBLACION, BAYOG, ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR 10-Nov-15 ZDS-CSC-2015-11-019 TRUCKING SERVICES NCR 10 DALIRI MULTI-PURPOSE COOPERATIVE 783 IRC COMPOUND GEN. LUIS ST., PASO DE BLAS, VALENZUELA CITY 01-Jun-16 NCR-CFO-78101-061516-046-N REPACKING / MANPOWER IVA 157 RAPTOR SECURITY AGENCY 2ND FLR., #777 LONDON ST., G7 CYPRESS VILLAGE, BRGY. STO. DOMINGO, CAINTA, RIZAL 02-Mar-16 ROIVA-RPO-18A-0316-005 SECURITY SERVICES NCR 168 MANPOWER SERVICES #8 SCOUT CHUATOCO ST., ROXAS DISTRICT, QUEZON CITY 24-Aug-16 NCR-QCFO-78101-081716-099 MANPOWER SERVICES NCR 1983 SECURITY AND INVESTIGATION CORPORATION G/F MARINOLD BLDG., B-52 L-48 PHASE 2, BRGY., PINAGSAMA, TAGUIG CITY 12-May-16 NCR-MUNTA-801000416-048 N SECURITY SERVICES NCR 1SIGMAFORCE SECURITY AGENCY CORPORATION 7F. OCAMPO AVE., MANUELA 4, BRGY. PAMPLONA TRES, LAS PIÑAS CITY 18-Nov-16 NCR-MUNTA-801000716-091 N SECURITY AGENCY NCR 1ST QUANTUM LEAP SECURITY AGENCY, INC. G/F LILI BLDG., 110 MALAKAS ST., BRGY. CENTRAL, DILIMAN, QUEZON CITY 11-Aug-15 NCR-QCFO-80100-081115-076 SECURITY SERVICES XII 2BOD GENERAL SERVICES CORPORATION APZ BUILDING, YUMANG STREET, DELFIN SUBD., SAN ISIDRO, GENERAL SANTOS CITY 25-Jul-16 MANPOWER/LABOR SERVICES IX 2C KINGS MANPWER AND JANITORIAL SERVICES COOPERATIVE DVN BLDG., M. -

In Search of Filipino Philosophy

IN SEARCH OF FILIPINO PHILOSOPHY PRECIOSA REGINA ANG DE JOYA B.A., M.A. (Ateneo de Manila) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2013 ii Acknowledgments My deepest thanks to friends and family who have accompanied me in this long and wonderful journey: to my parents, who taught me resilience and hardwork; to all my teachers who inspired me, and gently pushed me to paths I would not otherwise have had the courage to take; and friends who have shared my joys and patiently suffered my woes. Special thanks to my teachers: to my supervisor, Professor Reynaldo Ileto, for introducing me to the field of Southeast Asian Studies and for setting me on this path; to Dr. John Giordano, who never ceased to be a mentor; to Dr. Jan Mrazek, for introducing me to Javanese culture; Dr. Julius Bautista, for his insightful and invaluable comments on my research proposal; Professor Zeus Salazar, for sharing with me the vision and passions of Pantayong Pananaw; Professor Consolacion Alaras, who accompanied me in my pamumuesto; Pak Ego and Pak Kasidi, who sat with me for hours and hours, patiently unraveling the wisdom of Javanese thought; Romo Budi Subanar, S.J., who showed me the importance of humor, and Fr. Roque Ferriols, S.J., who inspired me to become a teacher. This journey would also have not been possible if it were not for the people who helped me along the way: friends and colleagues in the Ateneo Philosophy department, and those who have shared my passion for philosophy, especially Roy Tolentino, Michael Ner Mariano, P.J. -

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published By

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published by: NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE T.M. Kalaw St., Ermita, Manila Philippines Research and Publications Division: REGINO P. PAULAR Acting Chief CARMINDA R. AREVALO Publication Officer Cover design by: Teodoro S. Atienza First Printing, 1990 Second Printing, 1996 ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 003 — 4 (Hardbound) ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 006 — 9 (Softbound) FILIPINOS in HIS TOR Y Volume II NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 Republic of the Philippines Department of Education, Culture and Sports NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE FIDEL V. RAMOS President Republic of the Philippines RICARDO T. GLORIA Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports SERAFIN D. QUIASON Chairman and Executive Director ONOFRE D. CORPUZ MARCELINO A. FORONDA Member Member SAMUEL K. TAN HELEN R. TUBANGUI Member Member GABRIEL S. CASAL Ex-OfficioMember EMELITA V. ALMOSARA Deputy Executive/Director III REGINO P. PAULAR AVELINA M. CASTA/CIEDA Acting Chief, Research and Chief, Historical Publications Division Education Division REYNALDO A. INOVERO NIMFA R. MARAVILLA Chief, Historic Acting Chief, Monuments and Preservation Division Heraldry Division JULIETA M. DIZON RHODORA C. INONCILLO Administrative Officer V Auditor This is the second of the volumes of Filipinos in History, a com- pilation of biographies of noted Filipinos whose lives, works, deeds and contributions to the historical development of our country have left lasting influences and inspirations to the present and future generations of Filipinos. NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 MGA ULIRANG PILIPINO TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Lianera, Mariano 1 Llorente, Julio 4 Lopez Jaena, Graciano 5 Lukban, Justo 9 Lukban, Vicente 12 Luna, Antonio 15 Luna, Juan 19 Mabini, Apolinario 23 Magbanua, Pascual 25 Magbanua, Teresa 27 Magsaysay, Ramon 29 Makabulos, Francisco S 31 Malabanan, Valerio 35 Malvar, Miguel 36 Mapa, Victorino M. -

Philippine National Bibliography 2014

ISSN 0303-190X PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY 2014 Manila National Library of the Philippines 2015 i ___________________________________________________ Philippine national bibliography / National Library of the Philippines. - Manila : National Library of the Philippines, Jan. - Feb. 1974 (v. 1, no. 1)- . - 30 cm Bi-monthly with annual cumulation. v. 4 quarterly index. ISSN 0303-190X 1. Philippines - Imprints. 2. Philippines - Bibliography. I. Philippines. National Library 059.9921’015 ___________________________________________________ Copies distributed by the Collection Development Division, National Library of the Philippines, Manila ii PREFACE Philippine National Bibliography lists works published or printed in the Philippines by Filipino authors or about the Philippines even if published abroad. It is published quarterly and cumulated annually. Coverage Philippine National Bibliography lists the following categories of materials: (a) Copyrighted materials under Presidential Degree No. 49, the Decree on the Protection of Intellectual Property which include books, pamphlets and non-book materials such as cassette tapes, etc.; (b) Books, pamphlets and non-book materials not registered in the copyright office; (c) Government publications; (d) First issues of periodicals, annuals, yearbooks, directories, etc.; (e) Conference proceedings, seminar or workshop papers; (f) Titles reprinted in the Philippines under Presidential Decree No. 285 as amended by Presidential Decree No. 1203. Excluded are the following: (a) Certain publications such as department, bureau, company and office orders, memoranda, and circulars; (b) Legal documents and judicial decisions; and (c) Trade lists, catalogs, time tables and similar commercial documents. Arrangement Philippine National Bibliography is arranged in a classified sequence with author, title and series index and a subject index. iii Sample Entry Dewey Decimal Class No. -

THE GENESIS of the PHILIPPINE COMMUNIST PARTY Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. Dames Andrew Richardson School of Orienta

THE GENESIS OF THE PHILIPPINE COMMUNIST PARTY Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. dames Andrew Richardson School of Oriental and African Studies University of London September 198A ProQuest Number: 10673216 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673216 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Unlike communist parties elsewhere in Asia, the Partido Komunista sa Pilipinas (PKP) was constituted almost entirely by acti vists from the working class. Radical intellectuals, professionals and other middle class elements were conspicuously absent. More parti cularly, the PKP was rooted In the Manila labour movement and, to a lesser extent, in the peasant movement of Central Luzon. This study explores these origins and then examines the character, outlook and performance of the Party in the first three years of its existence (1930-33). Socialist ideas began to circulate during the early 1900s, but were not given durable organisational expression until 1922, when a Workers’ Party was formed. Led by cadres from the country's principal labour federation, the Congreso Obrero, this party aligned its policies increasingly with those of the Comintern. -

Silliman Journal a JOURNAL DEVOTED to DISCUSSION and INVESTIGATION in the HUMANITIES and SCIENCES VOLUME 58 NUMBER 1 | JANUARY to JUNE 2017

ARTICLE AUTHOR 1 Silliman Journal A JOURNAL DEVOTED TO DISCUSSION AND INVESTIGATION IN THE HUMANITIES AND SCIENCES VOLUME 58 NUMBER 1 | JANUARY TO JUNE 2017 IN THIS ISSUE Lily Fetalsana-Apura Maria Mercedes Arzadon Rosario Maxino-Baseleres Gina A. Fontejon-Bonior Ian Rosales Casocot Josefina Dizon Benjamina Flor Elenita Garcia Augustus Franco B. Jamias Serlie Jamias Carljoe Javier Zeny Sarabia-Panol Mark Anthony Mujer Quintos Andrea Gomez-Soluta JANUARY TO JUNE 2017 - VOLUME 58 NO. 1 2 ARTICLE TITLE The Silliman Journal is published twice a year under the auspices of Silliman University, Dumaguete City, Philippines. Entered as second class mail matter at Dumaguete City Post Office on 1 September 1954. Copyright © 2017 by the individual authors and Silliman Journal All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the authors or the publisher. ISSN 0037-5284 Opinions and facts contained in the articles published in this issue of Silliman Journal are the sole responsibility of the individual authors and not of the Editors, the Editorial Board, Silliman Journal, or Silliman University. Annual subscription rates are at PhP600 for local subscribers, and $35 for overseas subscribers. Subscription and orders for current and back issues should be addressed to The Business Manager Silliman Journal Silliman University Main Library 6200 Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental Philippines Issues are also available in microfilm format from University Microfilms International 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor Michigan 48106 USA Other inquiries regarding editorial policies and contributions may be addressed to the Silliman Journal Business Manager or the Editor at the following email address: [email protected]. -

Shang List 052316

ISSUER STOCKHOLDER TYPE STOCKHOLDER NO STOCKHOLDER NAME ADDRESS NATIONALITY SHARES A. T. DE CASTRO SECURITIES SUITE 701, 7/F AYALA TOWER AYALA AVENUE, SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211123 PH 535 CORPORATION MAKATI CITY G/F FORTUNE LIFE BUILDING 162 LEGASPI ST., SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211238 AAA SOUTHEAST EQUITIES, INC. PH 8 LEGASPI VILL. MAKATI, METRO MANILA UNIT E 2904-A PSE CENTER SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 80442 ABACUS SECURITIES CORPORATION EXCHANGE RD., ORTIGAS CENTER PH 2,049 PASIG CITY ALL ASIA SEC. MGMT. CORP. 7/F SYCIP-LAW ALL ALL ASIA SECURITIES MANAGEMENT SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211322 ASIA CENTER 105 PASEO DE ROXAS STREET PH 35 CORP. MAKATI CITY 5/F PACIFIC STAR BLDG., MAKATI SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 80257 AMON SECURITIES CORP. A/C#001-54011 PH 6 AVE COR GIL PUYAT MAKATI CITY 5/F PACIFIC STAR BUILDING MAKATI AVE. COR. GIL SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211303 AMON SECURITIES CORPORATION PH 98 PUYAT AVE MAKATI CITY AMON SECURITIES CORPORATION A/C # 10TH FLR., PACIFIC STAR BLDG. MAKATI AVENUE, SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211050 PH 982 001-33247 COR. SEN GIL PUYAT AVENUE, MAKATI, M. M. 3/F ASIAN PLAZA 1, SENATOR GIL J. PUYAT SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211014 ANSCOR HAGEDORN SECURITIES INC PH 285 AVENUE, MAKATI METRO MANILA 9TH FLR., METROBANK PLAZA BLDG SEN GIL J. SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211244 ASI SECURITIES, INC. PH 142 PUYAT AVENUE MAKATI, METRO MANILA A/C-CAXN1222 RM. 207 SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 80673 ASIAN CAPITAL EQUITIES, INC. PENINSULA COURT, PASEO DE ROXAS PH 785 COR., MAKATI AVE., MAKATI CITY SUITE 210 MAKATI STOCK EXCHANGE BLDG., SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. -

Philippine Muslims on Screen: from Villains to Heroes Vivienne Angeles Lasalle University, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 20 Issue 1 The 2015 International Conference on Religion Article 6 and Film in Istanbul 1-4-2016 Philippine Muslims on Screen: From Villains to Heroes Vivienne Angeles LaSalle University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Angeles, Vivienne (2016) "Philippine Muslims on Screen: From Villains to Heroes," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol20/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Philippine Muslims on Screen: From Villains to Heroes Abstract Early portrayals of Philippine Muslims in film show them not only as a people who profess a “heathen religion” but also whose culture is dominated by notions of superiority and violence against women and non- Muslims. This presentation is largely due to the colonial legacies of Spain and the United States, whose respective occupation of the Philippines was met with resistance by Muslims. Such negative portrayals made their way into early films as indicated by Brides of Sulu (1934) and The Real Glory (1939). This paper argues that representations of Philippine Muslims in films changed over time, depending on the prevailing government policies and perceptions of people on Christian-Muslim relations. The other films included for this paper are Badjao (1957), Perlas ng Silangan (Pearl of the Orient, 1969), Muslim Magnum .357 (1986), Mistah: Mga Mandirigma (Mistah: Warriors, 1994), Bagong Buwan (New Moon, 2001) and Captive (2012). -

2016 YCC Citations Final

The Film Desk of the Young Critics Circle The 27th Annual Circle Citations for Distinguished Achievement 2016in Film for + SINE SIPat: Recasting Roles and Images, Stars,Awards, and Criticism Thursday, 27 April 2017 Jorge B. Vargas Museum University of the Philippines Roxas Avenue, UP Campus Diliman, Quezon City | 1 } 2 The 27th Annual CIrcLE CItatIONS for Distinguished Achievement in 2016Film for + SINE SIPat: Recasting Roles and Images, Stars, Awards, and Criticism 3 4 The Citation he Film Desk of the Young Critics Circle (YCC) first gave its annual citations in film achievement in 1991, a year after the YCC was Torganized by 15 reviewers and critics. In their Declaration of Principles, the members expressed the belief that cultural texts always call for active readings, “interactions” in fact among different readers who have the “unique capacities to discern, to interpret, and to reflect... evolving a dynamic discourse in which the text provokes the most imaginative ideas of our time.” The Film Desk has always committed itself to the discussion of film in the various arenas of academe and media, with the hope of fostering an alternative and emergent articulation of film critical practice, even within the severely debilitating culture of “awards.” binigay ng Film Desk ng Young Critics Circle (YCC) ang unang taunang pagkilala nito sa kahusayan sa pelikula noong 1991, ang taon pagkaraang maitatag ang YCC ng labinlimang tagapagrebyu at kritiko. Sa kanilang IDeklarasyon ng mga Prinsipyo, ipinahayag ng mga miyembro ang paniniwala na laging bukas ang mga tekstong kultural sa aktibong pagbasa, sa “mga interaksiyon” ng iba’t ibang mambabasa na may “natatanging kakayahan para sumipat, magbigay-kahulugan, at mag-isip .. -

Audio/Visual Materials

Philippine Studies Audio-Visual Resources Available at Wong Audio-Visual Room, Sinclair Library University of Hawaii at Manoa Tel: (808) 956-8308 URL: http://www.sinclair.hawaii.edu/wavc/ Alamat ni Julian Makabayan (The minor kingdoms, the series chronicles the Legend life of Amaya, a daughter of a Datu and a of Julian Makabayan) slave, prophecized to be the one who would 2 videodiscs : sd., col. ; 4 3/4 inches, defeat the fierce Rajah Mangubat. Born as a Pasig City : Viva Video, Inc., 2003 princess, she was demoted to slave status as Rajah Mangubat slayed her father. Guided A rice farmer stands up for social justice by her kambal-ahas, she embarks on a during the period when Spain ruled the journey to avenge her father's death and Philippines. (In Tagalog with English eventually to defeat the person that has been subtitles) the root cause of her misery and the downfall of her beloved land. With these, UH MANOA DVD 6130 she must climb the social ladder, from being a slave, to being an alabay, to become a tribe leader, then a warrior, and eventually Aloha Philippines: The Sakada fulfill her destiny to become the most Generation powerful woman of her time. (In Tagalog with English subtitles) Sakada Generation 60 minutes, color with b&w sequences, 1/2 UH MANOA DVD 10895 inch, VHS. Honolulu, HI: KITV, 1996. Telecast March 14, 1996. American Adobo This program looks at the Filipino community in Hawai‘i, tracing its roots 90 years ago, to 103 minutes, color, 4 ¾ inch, DVD. the first sugar plantation immigrants called U.S.: First Look Home Entertainment sakadas.