Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emindanao Library an Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition)

eMindanao Library An Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition) Published online by Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, Hawaii July 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii I. Articles/Books 1 II. Bibliographies 236 III. Videos/Images 240 IV. Websites 242 V. Others (Interviews/biographies/dictionaries) 248 PREFACE This project is part of eMindanao Library, an electronic, digitized collection of materials being established by the Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. At present, this annotated bibliography is a work in progress envisioned to be published online in full, with its own internal search mechanism. The list is drawn from web-based resources, mostly articles and a few books that are available or published on the internet. Some of them are born-digital with no known analog equivalent. Later, the bibliography will include printed materials such as books and journal articles, and other textual materials, images and audio-visual items. eMindanao will play host as a depository of such materials in digital form in a dedicated website. Please note that some resources listed here may have links that are “broken” at the time users search for them online. They may have been discontinued for some reason, hence are not accessible any longer. Materials are broadly categorized into the following: Articles/Books Bibliographies Videos/Images Websites, and Others (Interviews/ Biographies/ Dictionaries) Updated: July 25, 2014 Notes: This annotated bibliography has been originally published at http://www.hawaii.edu/cps/emindanao.html, and re-posted at http://www.emindanao.com. All Rights Reserved. For comments and feedbacks, write to: Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa 1890 East-West Road, Moore 416 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Email: [email protected] Phone: (808) 956-6086 Fax: (808) 956-2682 Suggested format for citation of this resource: Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. -

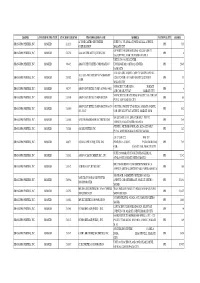

Department of Labor and Employment List of Contractors/Subcontractors Registered Under D.O

Department of Labor and Employment List of Contractors/Subcontractors registered under D.O. 18-A (as of March 2018) Date of Region Name of Establishments Address Registration Number Nature of Business Registration JANITORIAL AND GENERAL IVA @YOURSERVICE MANPOWER AND GENERAL SERVICES, INC. 702A OSMEÑA ST., BRGY. 3, LUCENA CITY, QUEZON 05-Jul-16 ROIVA-QPO-18A-0716-008 SERVICES IX 10 POBLACION, BAYOG, ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR 10-Nov-15 ZDS-CSC-2015-11-019 TRUCKING SERVICES NCR 10 DALIRI MULTI-PURPOSE COOPERATIVE 783 IRC COMPOUND GEN. LUIS ST., PASO DE BLAS, VALENZUELA CITY 01-Jun-16 NCR-CFO-78101-061516-046-N REPACKING / MANPOWER IVA 157 RAPTOR SECURITY AGENCY 2ND FLR., #777 LONDON ST., G7 CYPRESS VILLAGE, BRGY. STO. DOMINGO, CAINTA, RIZAL 02-Mar-16 ROIVA-RPO-18A-0316-005 SECURITY SERVICES NCR 168 MANPOWER SERVICES #8 SCOUT CHUATOCO ST., ROXAS DISTRICT, QUEZON CITY 24-Aug-16 NCR-QCFO-78101-081716-099 MANPOWER SERVICES NCR 1983 SECURITY AND INVESTIGATION CORPORATION G/F MARINOLD BLDG., B-52 L-48 PHASE 2, BRGY., PINAGSAMA, TAGUIG CITY 12-May-16 NCR-MUNTA-801000416-048 N SECURITY SERVICES NCR 1SIGMAFORCE SECURITY AGENCY CORPORATION 7F. OCAMPO AVE., MANUELA 4, BRGY. PAMPLONA TRES, LAS PIÑAS CITY 18-Nov-16 NCR-MUNTA-801000716-091 N SECURITY AGENCY NCR 1ST QUANTUM LEAP SECURITY AGENCY, INC. G/F LILI BLDG., 110 MALAKAS ST., BRGY. CENTRAL, DILIMAN, QUEZON CITY 11-Aug-15 NCR-QCFO-80100-081115-076 SECURITY SERVICES XII 2BOD GENERAL SERVICES CORPORATION APZ BUILDING, YUMANG STREET, DELFIN SUBD., SAN ISIDRO, GENERAL SANTOS CITY 25-Jul-16 MANPOWER/LABOR SERVICES IX 2C KINGS MANPWER AND JANITORIAL SERVICES COOPERATIVE DVN BLDG., M. -

La Mesa Hosts the Year's Biggest Family Event

December 2005 La Mesa hosts the year’s biggest family event By Chito S. Maniago Families came in droves as early as 8 a.m. on November 12 for the Family Wellness Festival at the La Mesa Eco Park, orga- ‘KBP: Serving the nized by ABS-CBN Foundation Inc. nation’... p.4 (AFI)-Bantay Kalikasan. The event kicked off with a spiritual earth ceremony led by AFI managing di- rector Gina Lopez and visiting space cleaner Shiela Gomez, one of 12 regis- tered “space clearers” in the world. Que- zon City mayor Feliciano Belmonte, MWSS administrator Orlando Hondrade and Senator Jamby Madrigal joined the ribbon-cutting ceremony to officially mark the start of the event. Among special guests were ABS-CBN chairman Eugenio Lopez III, Miss Earth 2005 Alexandra Braun Waldeck and ABS-CBN’s “Sports Unlimited” tandem Dyan Castillejo and Marc Nelson. The wellness festival gathered close to AFI’s Gina Lopez, Mayor Feliciano Belmonte, Miss Earth 2005 Alexandra Braun Waldeck 10,000 participants who attended various Meralco is a proud and Sen. Jamby Madrigal at the opening of the Wellness Festival on Nov. 12 Turn to page 6 sponsor of the 23rd Southeast Asian (SEA) Games, one of the Knowledge Channel in Tawi Tawi biggest sports events in …p.3 KNOWLEDGE Channel Foundation Inc. the region (KCFI) has launched Year 2 of its project, Television Education for the Advancement of Muslim Mindanao (dubbed TEAM- Mindanao) in Languyan Island, Tawi Tawi. The launch marked the initial entry of KC- FI into the Basulta (Basilan, Sulu, Tawi Tawi) area. TEAM-Mindanao is a USAID-assisted project which is providing some 150 pub- lic schools in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) with educa- tional television to help students in remote areas learn better and faster. -

20 Century Ends

New Year‟s Celebration 2013 20th CENTURY ENDS ANKIND yesterday stood on the threshold of a new millennium, linked by satellite technology for the most closely watched midnight in history. M The millennium watch was kept all over the world, from a sprinkle of South Pacific islands to the skyscrapers of the Americas, across the pyramids, the Parthenon and the temples of Angkor Wat. Manila Archbishop Luis Antonio Cardinal Tagle said Filipinos should greet 2013 with ''great joy'' and ''anticipation.'' ''The year 2013 is not about Y2K, the end of the world or the biggest party of a lifetime,'' he said. ''It is about J2K13, Jesus 2013, the Jubilee 2013 and Joy to the World 2013. It is about 2013 years of Christ's loving presence in the world.'' The world celebration was tempered, however, by unease over Earth's vulnerability to terrorism and its dependence on computer technology. The excitement was typified by the Pacific archipelago nation of Kiribati, so eager to be first to see the millennium that it actually shifted its portion of the international dateline two hours east. The caution was exemplified by Seattle, which canceled its New Year's party for fear of terrorism. In the Philippines, President Benigno Aquino III is bracing for a “tough” new year. At the same time, he called on Filipinos to pray for global peace and brotherhood and to work as one in facing the challenges of the 21st century. Mr. Estrada and at least one Cabinet official said the impending oil price increase, an expected P60- billion budget deficit, and the public opposition to amending the Constitution to allow unbridled foreign investments would make it a difficult time for the Estrada presidency. -

Art of Nation Building

SINING-BAYAN: ART OF NATION BUILDING Social Artistry Fieldbook to Promote Good Citizenship Values for Prosperity and Integrity PHILIPPINE COPYRIGHT 2009 by the United Nations Development Programme Philippines, Makati City, Philippines, UP National College of Public Administration and Governance, Quezon City and Bagong Lumad Artists Foundation, Inc. Edited by Vicente D. Mariano Editorial Assistant: Maricel T. Fernandez Border Design by Alma Quinto Project Director: Alex B. Brillantes Jr. Resident Social Artist: Joey Ayala Project Coordinator: Pauline S. Bautista Siningbayan Pilot Team: Joey Ayala, Pauline Bautista, Jaku Ayala Production Team: Joey Ayala Pauline Bautista Maricel Fernandez Jaku Ayala Ma. Cristina Aguinaldo Mercedita Miranda Vincent Silarde ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of research or review, as permitted under the copyright, this book is subject to the condition that it should not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, sold, or circulated in any form, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by applied laws. ALL SONGS COPYRIGHT Joey Ayala PRINTED IN THE PHILIPPINES by JAPI Printzone, Corp. Text Set in Garamond ISBN 978 971 94150 1 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS i MESSAGE Mary Ann Fernandez-Mendoza Commissioner, Civil Service Commission ii FOREWORD Bro. Rolando Dizon, FSC Chair, National Congress on Good Citizenship iv PREFACE: Siningbayan: Art of Nation Building Alex B. Brillantes, Jr. Dean, UP-NCPAG vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii INTRODUCTION Joey Ayala President, Bagong Lumad Artists Foundation Inc.(BLAFI) 1 Musical Reflection: KUNG KAYA MONG ISIPIN Joey Ayala 2 SININGBAYAN Joey Ayala 5 PART I : PAGSASALOOB (CONTEMPLACY) 9 “BUILDING THE GOOD SOCIETY WE WANT” My Hope as a Teacher in Political and Governance Jose V. -

In Search of Filipino Philosophy

IN SEARCH OF FILIPINO PHILOSOPHY PRECIOSA REGINA ANG DE JOYA B.A., M.A. (Ateneo de Manila) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2013 ii Acknowledgments My deepest thanks to friends and family who have accompanied me in this long and wonderful journey: to my parents, who taught me resilience and hardwork; to all my teachers who inspired me, and gently pushed me to paths I would not otherwise have had the courage to take; and friends who have shared my joys and patiently suffered my woes. Special thanks to my teachers: to my supervisor, Professor Reynaldo Ileto, for introducing me to the field of Southeast Asian Studies and for setting me on this path; to Dr. John Giordano, who never ceased to be a mentor; to Dr. Jan Mrazek, for introducing me to Javanese culture; Dr. Julius Bautista, for his insightful and invaluable comments on my research proposal; Professor Zeus Salazar, for sharing with me the vision and passions of Pantayong Pananaw; Professor Consolacion Alaras, who accompanied me in my pamumuesto; Pak Ego and Pak Kasidi, who sat with me for hours and hours, patiently unraveling the wisdom of Javanese thought; Romo Budi Subanar, S.J., who showed me the importance of humor, and Fr. Roque Ferriols, S.J., who inspired me to become a teacher. This journey would also have not been possible if it were not for the people who helped me along the way: friends and colleagues in the Ateneo Philosophy department, and those who have shared my passion for philosophy, especially Roy Tolentino, Michael Ner Mariano, P.J. -

Philippine National Bibliography 2014

ISSN 0303-190X PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY 2014 Manila National Library of the Philippines 2015 i ___________________________________________________ Philippine national bibliography / National Library of the Philippines. - Manila : National Library of the Philippines, Jan. - Feb. 1974 (v. 1, no. 1)- . - 30 cm Bi-monthly with annual cumulation. v. 4 quarterly index. ISSN 0303-190X 1. Philippines - Imprints. 2. Philippines - Bibliography. I. Philippines. National Library 059.9921’015 ___________________________________________________ Copies distributed by the Collection Development Division, National Library of the Philippines, Manila ii PREFACE Philippine National Bibliography lists works published or printed in the Philippines by Filipino authors or about the Philippines even if published abroad. It is published quarterly and cumulated annually. Coverage Philippine National Bibliography lists the following categories of materials: (a) Copyrighted materials under Presidential Degree No. 49, the Decree on the Protection of Intellectual Property which include books, pamphlets and non-book materials such as cassette tapes, etc.; (b) Books, pamphlets and non-book materials not registered in the copyright office; (c) Government publications; (d) First issues of periodicals, annuals, yearbooks, directories, etc.; (e) Conference proceedings, seminar or workshop papers; (f) Titles reprinted in the Philippines under Presidential Decree No. 285 as amended by Presidential Decree No. 1203. Excluded are the following: (a) Certain publications such as department, bureau, company and office orders, memoranda, and circulars; (b) Legal documents and judicial decisions; and (c) Trade lists, catalogs, time tables and similar commercial documents. Arrangement Philippine National Bibliography is arranged in a classified sequence with author, title and series index and a subject index. iii Sample Entry Dewey Decimal Class No. -

Pdabs363.Pdf

COASTAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PROJECT PHILIPPINES SPECIAL MID-TERM REPORT 1997 2001 1996 1998 1999 2000 2002 CRMP IN MID-STREAM: ON COURSE TO A THRESHOLD OF SUSTAINED COASTAL MANAGEMENT IN THE PHILIPPINES COASTAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PROJECT IMPLEMENTED BY DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES SUPPORTED BY UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PREPARED BY TETRA TECH EM INC. UNDER USAID CONTRACT NO. AID-492-0444-C-00-6028-00 CRMP in Mid-Stream: On Course to a Threshold of Sustained Coastal Management in the Philipppines 2000 PRINTED IN CEBU CITY, PHILIPPINES Citation: CRMP. 2000. CRMP in Mid-Stream: On Course to a Threshold of Sustained Coastal Management in the Philippines. Special Mid-term Report (1996-1999), Coastal Resource Management Project, Cebu City, Philippines, 100pp. This publication was made possible through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms and conditions of Contract No. AID-492-0444-C-00- 6028-00 supporting the Coastal Resource Management Project. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID. This publication may be reproduced or quoted in other publications as long as proper reference is made to the source. CRMP Document No. 09-CRM/2000 ISBN 971-91925-5-0 contents List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................ v Preface ............................................................................................................................................... -

The Organic Intellectual in Filipino Drama 1903-1907

UNITAS The Organic Intellectual in Filipino Drama 1903-1907 From Resistance to Agency . VOL. 87 • NO. 2 • NOVEMBER 2014 UNITAS semi-annual peer-reviewed international online journal of advanced research in literature, culture, and society The Organic Intellectual in Filipino Drama 1903-1907 From Resistance to Agency Jennifer Bermudez Indexed in the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America The Organic Intellectual in Filipino Drama 1903-1907: From Resistance to Agency Copyright © 2014 Jennifer Bermudez and the University of Santo Tomas About the Book Cover The interior of Teatro Zorilla. Photo was taken from the website, All About Juan. (“The Teatro Zorilla.” All About Juan, 29 Sept. 2014, http:// all-about-juan.info/2014/09/teatro-zorrilla/) Photo of Aurelio Tolentino. Taken from Noel Barcelona’s blog Dreams and Other Musings. (Barcelona, Noel. Photo of Aurelio Tolentino.”Aurelio Tolentino and His Play Kahapon, Ngayon, at Bukas,” Dreams and Other Musings, 16 May 2009, http://pagguguniguni.blogspot.com/2009/05/ aurelio-tolentino-and-his-play-kahapon.html) Layout by Paolo Miguel G. Tiausas UNITAS Logo by Francisco T. Reyes ISSN: 2619-7987 ISSN: 0041-7149 UNITAS is an international online peer-reviewed open-access journal of advanced research in literature, culture, and society published bi-annually (May and November). UNITAS is published by the University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines, the oldest university in Asia. It is hosted by the Department of Literature, with its editorial address at the Office of the Scholar-in-Residence under the auspices of the Faculty of Arts and Letters. Hard copies are printed on demand or in a limited edition. -

Shang List 052316

ISSUER STOCKHOLDER TYPE STOCKHOLDER NO STOCKHOLDER NAME ADDRESS NATIONALITY SHARES A. T. DE CASTRO SECURITIES SUITE 701, 7/F AYALA TOWER AYALA AVENUE, SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211123 PH 535 CORPORATION MAKATI CITY G/F FORTUNE LIFE BUILDING 162 LEGASPI ST., SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211238 AAA SOUTHEAST EQUITIES, INC. PH 8 LEGASPI VILL. MAKATI, METRO MANILA UNIT E 2904-A PSE CENTER SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 80442 ABACUS SECURITIES CORPORATION EXCHANGE RD., ORTIGAS CENTER PH 2,049 PASIG CITY ALL ASIA SEC. MGMT. CORP. 7/F SYCIP-LAW ALL ALL ASIA SECURITIES MANAGEMENT SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211322 ASIA CENTER 105 PASEO DE ROXAS STREET PH 35 CORP. MAKATI CITY 5/F PACIFIC STAR BLDG., MAKATI SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 80257 AMON SECURITIES CORP. A/C#001-54011 PH 6 AVE COR GIL PUYAT MAKATI CITY 5/F PACIFIC STAR BUILDING MAKATI AVE. COR. GIL SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211303 AMON SECURITIES CORPORATION PH 98 PUYAT AVE MAKATI CITY AMON SECURITIES CORPORATION A/C # 10TH FLR., PACIFIC STAR BLDG. MAKATI AVENUE, SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211050 PH 982 001-33247 COR. SEN GIL PUYAT AVENUE, MAKATI, M. M. 3/F ASIAN PLAZA 1, SENATOR GIL J. PUYAT SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211014 ANSCOR HAGEDORN SECURITIES INC PH 285 AVENUE, MAKATI METRO MANILA 9TH FLR., METROBANK PLAZA BLDG SEN GIL J. SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211244 ASI SECURITIES, INC. PH 142 PUYAT AVENUE MAKATI, METRO MANILA A/C-CAXN1222 RM. 207 SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 80673 ASIAN CAPITAL EQUITIES, INC. PENINSULA COURT, PASEO DE ROXAS PH 785 COR., MAKATI AVE., MAKATI CITY SUITE 210 MAKATI STOCK EXCHANGE BLDG., SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. -

Philippine Muslims on Screen: from Villains to Heroes Vivienne Angeles Lasalle University, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 20 Issue 1 The 2015 International Conference on Religion Article 6 and Film in Istanbul 1-4-2016 Philippine Muslims on Screen: From Villains to Heroes Vivienne Angeles LaSalle University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Angeles, Vivienne (2016) "Philippine Muslims on Screen: From Villains to Heroes," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol20/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Philippine Muslims on Screen: From Villains to Heroes Abstract Early portrayals of Philippine Muslims in film show them not only as a people who profess a “heathen religion” but also whose culture is dominated by notions of superiority and violence against women and non- Muslims. This presentation is largely due to the colonial legacies of Spain and the United States, whose respective occupation of the Philippines was met with resistance by Muslims. Such negative portrayals made their way into early films as indicated by Brides of Sulu (1934) and The Real Glory (1939). This paper argues that representations of Philippine Muslims in films changed over time, depending on the prevailing government policies and perceptions of people on Christian-Muslim relations. The other films included for this paper are Badjao (1957), Perlas ng Silangan (Pearl of the Orient, 1969), Muslim Magnum .357 (1986), Mistah: Mga Mandirigma (Mistah: Warriors, 1994), Bagong Buwan (New Moon, 2001) and Captive (2012). -

2016 YCC Citations Final

The Film Desk of the Young Critics Circle The 27th Annual Circle Citations for Distinguished Achievement 2016in Film for + SINE SIPat: Recasting Roles and Images, Stars,Awards, and Criticism Thursday, 27 April 2017 Jorge B. Vargas Museum University of the Philippines Roxas Avenue, UP Campus Diliman, Quezon City | 1 } 2 The 27th Annual CIrcLE CItatIONS for Distinguished Achievement in 2016Film for + SINE SIPat: Recasting Roles and Images, Stars, Awards, and Criticism 3 4 The Citation he Film Desk of the Young Critics Circle (YCC) first gave its annual citations in film achievement in 1991, a year after the YCC was Torganized by 15 reviewers and critics. In their Declaration of Principles, the members expressed the belief that cultural texts always call for active readings, “interactions” in fact among different readers who have the “unique capacities to discern, to interpret, and to reflect... evolving a dynamic discourse in which the text provokes the most imaginative ideas of our time.” The Film Desk has always committed itself to the discussion of film in the various arenas of academe and media, with the hope of fostering an alternative and emergent articulation of film critical practice, even within the severely debilitating culture of “awards.” binigay ng Film Desk ng Young Critics Circle (YCC) ang unang taunang pagkilala nito sa kahusayan sa pelikula noong 1991, ang taon pagkaraang maitatag ang YCC ng labinlimang tagapagrebyu at kritiko. Sa kanilang IDeklarasyon ng mga Prinsipyo, ipinahayag ng mga miyembro ang paniniwala na laging bukas ang mga tekstong kultural sa aktibong pagbasa, sa “mga interaksiyon” ng iba’t ibang mambabasa na may “natatanging kakayahan para sumipat, magbigay-kahulugan, at mag-isip ..