St. Marks River and Apalachee Bay Surface Water Improvement and Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comprehensive River Management Plan

September 2011 ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT WEKIVA WILD AND SCENIC RIVER SYSTEM Florida __________________________________________________________________________ The Wekiva Wild and Scenic River System was designated by an act of Congress on October 13, 2000 (Public Law 106-299). The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (16 USC 1247) requires that each designated river or river segment must have a comprehensive river management plan developed. The Wekiva system has no approved plan in place. This document examines two alternatives for managing the Wekiva River System. It also analyzes the impacts of implementing each of the alternatives. Alternative A consists of the existing river management and trends and serves as a basis for comparison in evaluating the other alternative. It does not imply that no river management would occur. The concept for river management under alternative B would be an integrated program of goals, objectives, and actions for protecting and enhancing each outstandingly remarkable value. A coordinated effort among the many public agencies and entities would be needed to implement this alternative. Alternative B is the National Park Service’s and the Wekiva River System Advisory Management Committee’s preferred alternative. Implementing the preferred alternative (B) would result in coordinated multiagency actions that aid in the conservation or improvement of scenic values, recreation opportunities, wildlife and habitat, historic and cultural resources, and water quality and quantity. This would result in several long- term beneficial impacts on these outstandingly remarkable values. This Environmental Assessment was distributed to various agencies and interested organizations and individuals for their review and comment in August 2010, and has been revised as appropriate to address comments received. -

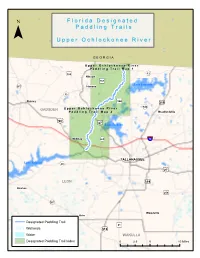

Upper Ochlockonee River Paddling Guide

F ll o r ii d a D e s ii g n a tt e d ¯ P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll s U p p e r O c h ll o c k o n e e R ii v e r G E O R G I A U p p e rr O c h ll o c k o n e e R ii v e rr P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 1 159 «¬12 )" Hinson )"157 343 Lake Iamonia )" «¬267 Havana «¬12 344 Quincy )" ¤£319 342 GADSDEN U p p e rr O c h ll o c k o n e e R ii v e rr «¬ P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 2 Bradfordville 90 ¤£ 27 ¤£ Lake Jackson Midway «¬263 ¨¦§10 1)"541 Capitola TALLAHASSEE Lake Talquin «¬20 «¬267 ¤£27 LEON ¤£319 Bloxham )"259 «¬267 Woodville Helen Designated Paddling Trail )"61 Wetlands ¤£319 Water WAKULLA Designated Paddling Trail Index 0 2.5 5 10 Miles 319 ¤£ 61 Newport Arran )" U p p e rr O c h ll o c k o n e e R ii v e rr P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 1 ¯ Bell Rd d R d or n c Co o ir a C !| River Ridge «¬12 Plantation Concord Conservation Easement Access Point 1: SR 12 N: 30.6689 W: -84.3051 Havana Hiamonee à Plantation Conservation «¬12 Easement River Ridge Plantation C Conservation o n c Easement o d r R d n a R i id d r e M Kemp Rd N E D Tall Timbers Research Station S D & Land Conservancy A N O G E L Lake Iamonia I ro n B r id g e R d d Pond R ard ch Or !| Mallard Pond Access Point 2: Old Bainbridge Rd Bridge N: 30.5858 W: -84.3594 O l d B Carr Lake a i n b r i d Upper Ochlockonee River Paddling Trail g e R Canoe/Kayak Launch d !| Conservation Lands 27 0 0.5 1 2 Miles ¤£ Wetlands ¯ U p p e rr O c h ll o c k o n e e R ii v e rr P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 2 )"270 RCM Farms Conservation Easement O l d B a i -

Exhibit Specimen List FLORIDA SUBMERGED the Cretaceous, Paleocene, and Eocene (145 to 34 Million Years Ago) PARADISE ISLAND

Exhibit Specimen List FLORIDA SUBMERGED The Cretaceous, Paleocene, and Eocene (145 to 34 million years ago) FLORIDA FORMATIONS Avon Park Formation, Dolostone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; with echinoid sand dollar fossil (Periarchus lyelli); specimen from Florida Geological Survey Avon Park Formation, Limestone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; with organic layers containing seagrass remains from formation in shallow marine environment; specimen from Florida Geological Survey Ocala Limestone (Upper), Limestone from Eocene time; Jackson County, Florida; with foraminifera; specimen from Florida Geological Survey Ocala Limestone (Lower), Limestone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; specimens from Tanner Collection OTHER Anhydrite, Evaporite from early Cenozoic time; Unknown location, Florida; from subsurface core, showing evaporite sequence, older than Avon Park Formation; specimen from Florida Geological Survey FOSSILS Tethyan Gastropod Fossil, (Velates floridanus); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Barge Canal spoil island, Levy County, Florida; specimen from Tanner Collection Echinoid Sea Biscuit Fossils, (Eupatagus antillarum); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Barge Canal spoil island, Levy County, Florida; specimens from Tanner Collection Echinoid Sea Biscuit Fossils, (Eupatagus antillarum); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Mouth of Withlacoochee River, Levy County, Florida; specimens from John Sacha Collection PARADISE ISLAND The Oligocene (34 to 23 million years ago) FLORIDA FORMATIONS Suwannee -

Burned to Be Wild: Science, Society, and Ecological Conservation In

BURNED TO BE WILD: SCIENCE, SOCIETY, AND ECOLOGICAL CONSERVATION IN THE SOUTHERN LONGLEAF PINE by ALBERT GLOVER WAY (Under the Direction of Paul S. Sutter) ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the development of ecological conservation and science in the southern coastal plain’s dominant ecosystem – the longleaf pine-grassland forest. It examines how the impetus for conservation changed over the long twentieth-century from concerns over bodily health, landscape aesthetics, and recreation, into concerns for ecological integrity and landscape diversity, and argues that the biocentric turn in twentieth-century science and society was rooted in the very processes of production that it sought to moderate. To unearth this story, it focuses on the region surrounding Thomasville, Georgia and Tallahassee, Florida, known as the Red Hills, where wealthy northerners came after the Civil War and Reconstruction in search of health, and remained to convert failing farms and plantations into winter retreats and hunting preserves. In the years covered here, roughly 1880-1960, this land of wealth and poverty was a working landscape that produced a variety of goods and supported a large number of people; yet, at the same time it was a conservation landscape and laboratory where a great deal of scientific knowledge about the longleaf pine-grassland environment came to light. The central figure in this dissertation is Herbert L. Stoddard, an ornithologist, wildlife biologist, and ecological forester who came to the Red Hills in 1924 as an agent of the U.S. Bureau of the Biological Survey to examine the life history and preferred habitat of the bobwhite quail. -

A Light in the Dark: Illuminating the Maritime Past of The

A LIGHT IN THE DARK: ILLUMINATING THE MARITIME PAST OF THE BLACKWATER RIVER by Benjamin Charles Wells B.A., Mercyhurst University, 2010 A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida For partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 © 2015 Benjamin Charles Wells The thesis of Benjamin Charles Wells is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory D. Cook, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ Brian R. Rucker, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ Della A. Scott-Ireton, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ John R. Bratten, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ John Clune, Ph.D., Interim AVP for Academic Programs Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project would not have been possible without the help of numerous individuals. First and foremost, a massive thank you to my committee—Dr. Della Scott-Ireton, Dr. Greg Cook, and Dr. Brian Rucker. The University of West Florida Archaeology Institute supplied the materials and financial support to complete the field work. Steve McLin, Fritz Sharar, and Del de Los Santos maintained the boats and diving equipment for operations. Cindi Rogers, Juliette Moore, and Karen Mims – you three ladies saved me, and encouraged me more than you will ever know. To those in the Department of Anthropology who provided assistance and support, thank you. Field work would not have occurred without the graduate and undergraduate students in the 2013 and 2014 field schools and my fellow graduate students on random runs to the river. -

Wakulla County Wakulla

MAP INSIDE! MAP printed on recycled paper using vegetable-based ink. vegetable-based using paper recycled on printed . http://www.fl-seafood.com visit recipes, seafood MARINA LOCATOR MARINA sustainable printing practices. This document is is document This practices. printing sustainable RAMP & Recipe courtesy of Fresh from Florida Seafood. For more more For Seafood. Florida from Fresh of courtesy Recipe Florida Sea Grant is committed to responsible and and responsible to committed is Grant Sea Florida BOAT fresh dill and season with freshly ground pepper. pepper. ground freshly with season and dill fresh 2017 July SGEF-244 your choice, such as angel hair. Garnish with with Garnish hair. angel as such choice, your Serve immediately over prepared pasta of of pasta prepared over immediately Serve http://myfwc.com scallops. scallops. Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission Wildlife and Fish Florida and pepper to taste. Stir for 3 minutes and add add and minutes 3 for Stir taste. to pepper and over medium-low heat; add 2 cloves garlic, salt salt garlic, cloves 2 add heat; medium-low over Wipe out skillet, then melt 1/2 cup butter butter cup 1/2 melt then skillet, out Wipe scallops from skillet and set aside. aside. set and skillet from scallops Overcooking makes the texture rubbery. Remove Remove rubbery. texture the makes Overcooking medium heat. Stir until opaque, about 1 minute. minute. 1 about opaque, until Stir heat. medium tablespoons melted butter in a large skillet over over skillet large a in butter melted tablespoons and limits, contact: limits, and Sauté 3 pounds Florida scallops in 2 2 in scallops Florida pounds 3 Sauté seasons open requirements, license beds, collecting the scallops by hand. -

Florida Marine Research Institute

ISSN 1092-194X FLORIDA MARINE RESEARCH INSTITUTE TECHNICALTECHNICAL REPORTSREPORTS Florida’s Shad and River Herrings (Alosa species): A Review of Population and Fishery Characteristics Richard S. McBride Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission FMRI Technical Report TR-5 2000 Jeb Bush Governor of Florida Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission Allan E. Egbert Executive Director The Florida Marine Research Institute (FMRI) is a division of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Con- servation Commission (FWC). The FWC is “managing fish and wildlife resources for their long- term well-being and the benefit of people.” The FMRI conducts applied research pertinent to managing marine-fishery resources and marine species of special concern in Florida. Programs at the FMRI focus on resource-management topics such as managing gamefish and shellfish populations, restoring depleted fish stocks and the habitats that support them, pro- tecting coral reefs, preventing and mitigating oil-spill damage, protecting endangered and threatened species, and managing coastal-resource information. The FMRI publishes three series: Memoirs of the Hourglass Cruises, Florida Marine Research Publi- cations, and FMRI Technical Reports. FMRI Technical Reports contain information relevant to imme- diate resource-management needs. Kenneth D. Haddad, Chief of Research James F. Quinn, Jr., Science Editor Institute Editors Theresa M. Bert, Paul R. Carlson, Mark M. Leiby, Anne B. Meylan, Robert G. Muller, Ruth O. Reese Judith G. Leiby, Copy Editor Llyn C. French, Publications Production Florida’s Shad and River Herrings (Alosa species): A Review of Population and Fishery Characteristics Richard S. McBride Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Florida Marine Research Institute 100 Eighth Avenue Southeast St. -

11-1 335-6-11-.02 Use Classifications. (1) the ALABAMA RIVER BASIN Waterbody from to Classification ALABAMA RIVER MOBILE RIVER C

335-6-11-.02 Use Classifications. (1) THE ALABAMA RIVER BASIN Waterbody From To Classification ALABAMA RIVER MOBILE RIVER Claiborne Lock and F&W Dam ALABAMA RIVER Claiborne Lock and Alabama and Gulf S/F&W (Claiborne Lake) Dam Coast Railway ALABAMA RIVER Alabama and Gulf River Mile 131 F&W (Claiborne Lake) Coast Railway ALABAMA RIVER River Mile 131 Millers Ferry Lock PWS (Claiborne Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Millers Ferry Sixmile Creek S/F&W (Dannelly Lake) Lock and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Sixmile Creek Robert F Henry Lock F&W (Dannelly Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Robert F Henry Lock Pintlala Creek S/F&W (Woodruff Lake) and Dam ALABAMA RIVER Pintlala Creek Its source F&W (Woodruff Lake) Little River ALABAMA RIVER Its source S/F&W Chitterling Creek Within Little River State Forest S/F&W (Little River Lake) Randons Creek Lovetts Creek Its source F&W Bear Creek Randons Creek Its source F&W Limestone Creek ALABAMA RIVER Its source F&W Double Bridges Limestone Creek Its source F&W Creek Hudson Branch Limestone Creek Its source F&W Big Flat Creek ALABAMA RIVER Its source S/F&W 11-1 Waterbody From To Classification Pursley Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Beaver Creek ALABAMA RIVER Extent of reservoir F&W (Claiborne Lake) Beaver Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Cub Creek Beaver Creek Its source F&W Turkey Creek Beaver Creek Its source F&W Rockwest Creek Claiborne Lake Its source F&W Pine Barren Creek Dannelly Lake Its source S/F&W Chilatchee Creek Dannelly Lake Its source S/F&W Bogue Chitto Creek Dannelly Lake Its source F&W Sand Creek Bogue -

Florida Historical Uarterly

The Florida Historical uarterly APRIL 1970 PUBLISHED BY THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY FRONT COVER “A View of Pensacola in West Florida” is a black and white engraving published and dedicated by George Gauld to Sir William Burnaby, rear admiral and commander of the British fleet at Jamaica. From the British ensigns on the vessels and the flag flying from the flagstaff, this is obviously a picture of Pensacola during the British period. Since Gauld’s name is not mentioned in any reference sources as an engraver, and since such a skill is not mentioned in his book, it is unlikely that he was the engraver of this picture, but he probably drew the sketch of the scene from which it was made. The engraving is in the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. Gauld, surveyor of the coasts of Florida, was born in 1732 at Ardbrack, Bamffshire, and he was educated at King’s College, Aberdeen. In 1763 he was appointed to make a survey of all newly acquired English territory in the West Indies, and in March of the following year he sailed aboard the Tartar for Jamaica to join Burnaby’s fleet. In August 1764 he accompanied Sir John Lindsay to Pensacola and he may have made a sketch of the harbor at that time. He was a friend of Philip Pittman, author of The Present State of the European Settlements on the Mississippi . (1770), and Thomas Hutchins whose An Historical Narrative and Topogaphical Description of Louisiana, and West-Florida was published in 1784. They helped him draft charts and plans of West Florida. -

State-Designated Paddling Trails Paddling Guides

State-Designated Paddling Trails Paddling Guides Compiled from (http://www.dep.state.fl.us/gwt/guide/paddle.htm) This paddling guide can be downloaded at http://www.naturalnorthflorida.com/download-center/ Last updated March 16, 2016 The Original Florida Tourism Task Force 2009 NW 67th Place Gainesville, FL 32653-1603 352.955.2200 ∙ 877.955.2199 Table of Contents Chapter Page Florida’s Designated Paddling Trails 1 Aucilla River 3 Ichetucknee River 9 Lower Ochlockonee River 13 Santa Fe River 23 Sopchoppy River 29 Steinhatchee River 39 Wacissa River 43 Wakulla River 53 Withlacoochee River North 61 i ii Florida’s Designated Paddling Trails From spring-fed rivers to county blueway networks to the 1515-mile Florida Circumnavigational Saltwater Paddling Trail, Florida is endowed with exceptional paddling trails, rich in wildlife and scenic beauty. If you want to explore one or more of the designated trails, please read through the following descriptions, click on a specific trail on our main paddling trail page for detailed information, and begin your adventure! The following maps and descriptions were compiled from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the Florida Office of Greenways and Trails. It was last updated on March 16, 2016. While we strive to keep our information current, the most up-to-date versions are available on the OGT website: http://www.dep.state.fl.us/gwt/guide/paddle.htm The first Florida paddling trails were designated in the early 1970s, and trails have been added to the list ever since. Total mileage for the state-designated trails is now around 4,000 miles. -

Strategic Habitat and River Reach Units for Aquatic Species of Conservation Concern in Alabama by E

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA SPECIAL MAP 248 Strategic Habitat and River Reach Units for Aquatic Species of Conservation Concern in Alabama by E. Anne Wynn, Patrick E. O'Neil, and Stuart W. McGregor - Geological Survey of Alabama; Jeffrey R. Powell, Jennifer M. Pritchett, and Anthony D. Ford - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist and Paul D. Johnson - Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources TENNESSEE Explanation Rivers and streams 4 Open water County lines 3 5 8 9 Hydrologic Unit Code (HUC) 10 LAUDERDALE 6 subregion boundary LIMESTONE Strategic Habitat Unit (SHU) 2 39 MADISON JACKSON COLBERT Strategic River Reach Unit (SRRU) LAWRENCE FRANKLIN 7 MORGAN The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service DE KALB 1 MARSHALL in conjunction with the Alabama 20 22 CHEROKEE Department of Conservation and MARION Natural Resources and the Geological 18 37 CULLMAN GEORGIA Survey of Alabama have selected WINSTON BLOUNT ETOWAH watersheds and river segments in the five 19 38 major HUC 4 subregions in Alabama to focus 23 36 conservation activities for managing, recovering, FAYETTE WALKER LAMAR ST CLAIR 35 and restoring populations of rare fishes, mussels, 21 41 CALHOUN snails, and crayfishes. These Strategic Habitat Units 17 CLEBURNE 14 (SHUs) and Strategic River Reach Units (SRRUs) 32 33 JEFFERSON include a substantial part of Alabama’s remaining 16 34 high-quality water courses and reflect the variety of aquatic 31 RANDOLPH habitats occupied by these species historically and presently. MISSISSIPPI 30 PICKENS 15 The SHUs were selected based on the presence of federally CLAY SHELBY listed and state imperiled species, potential threats to the TUSCALOOSA TALLADEGA 27 species, designation of critical habitat, and the best available 29 TALLAPOOSA information about the essential habitat components required by 13 BIBB CHAMBERS these aquatic species to survive. -

Black Creek Crayfish (Procambarus Pictus) Species Status Assessment

Black Creek Crayfish (Procambarus pictus) Species Status Assessment Version 1.0 Photo by Christopher Anderson July 2020 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service South Atlantic, Gulf & Mississippi Basin Regions Atlanta, GA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document was prepared by Kathryn N. Smith-Hicks (Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute), Heath Rauschenberger (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [Service]), Lourdes Mena (Service), David Cook (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission [FWC]), and Erin Rivenbark (Service). Other species expertise, guidance, and document reviews were provided by Paul Moler (FWC), Gary Warren (FWC), Lindsey Reisinger (University of Florida), Katherine Lawlor (FWC), Kristi Lee (FWC), and Kasey Fralick (FWC). Additionally, peer reviewers including Troy Keller and Chester R. Figiel, Jr. provided valuable input into the analysis and reviews of a draft of this document. We appreciate their input and comments, which resulted in a more robust status assessment and final report. Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2020. Species status assessment report for Procambarus pictus (Black Creek crayfish), Version 1.0. July 2020. Atlanta, Georgia. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Black Creek crayfish (Procambarus pictus) are small to medium sized crayfish endemic to four northeastern Florida counties (Clay, Duval, Putnam, and St. Johns) in the Lower St. Johns River Basin. Black Creek crayfish rely on cool, flowing, sand-bottomed, and tannic-stained streams that are highly oxygenated. Locations that fulfill the species’ habitat requirements are typically headwater sections of streams that maintain a constant flow; however, they are found in small and large tributary streams. Within these streams, Black Creek crayfish require aquatic vegetation and debris for shelter with alternation of shaded and open canopy cover where they eat aquatic plants, dead plant and animal material, and detritus.