Chapter 1: the Everglades to the 1920S Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Everglades: Wetlands Not Wastelands Marjory Stoneman Douglas Overcoming the Barriers of Public Unawareness and the Profit Motive in South Florida

The Everglades: Wetlands not Wastelands Marjory Stoneman Douglas Overcoming the Barriers of Public Unawareness and the Profit Motive in South Florida Manav Bansal Senior Division Historical Paper Paper Length: 2,496 Bansal 1 "Marjory was the first voice to really wake a lot of us up to what we were doing to our quality of life. She was not just a pioneer of the environmental movement, she was a prophet, calling out to us to save the environment for our children and our grandchildren."1 - Florida Governor Lawton Chiles, 1991-1998 Introduction Marjory Stoneman Douglas was a vanguard in her ideas and approach to preserve the Florida Everglades. She not only convinced society that Florida’s wetlands were not wastelands, but also educated politicians that its value transcended profit. From the late 1800s, attempts were underway to drain large parts of the Everglades for economic gain.2 However, from the mid to late 20th century, Marjory Stoneman Douglas fought endlessly to bring widespread attention to the deteriorating Everglades and increase public awareness regarding its importance. To achieve this goal, Douglas broke societal, political, and economic barriers, all of which stemmed from the lack of familiarity with environmental conservation, apathy, and the near-sighted desire for immediate profit without consideration for the long-term impacts on Florida’s ecosystem. Using her voice as a catalyst for change, she fought to protect the Everglades from urban development and draining, two actions which would greatly impact the surrounding environment, wildlife, and ultimately help mitigate the effects of climate change. By educating the public and politicians, she served as a model for a new wave of environmental activism and she paved the way for the modern environmental movement. -

Everglades Biographies Everglades Biographies

Everglades Digital Library Guide to Collection Everglades Timeline Everglades Biographies Everglades Biographies Research Help Everglades Librarian Ordering Reproductions Copyright Credits Home Search the Expanded Collection Browse the Expanded Collection Bowman F. Ashe James Edmundson Ingraham Ivar Axelson James Franklin Jaudon Mary McDougal Axelson May Mann Jennings Access the Original Richard J. Bolles Claude Carson Matlack Collection at Chief Billy Bowlegs Daniel A. McDougal Guy Bradley Minnie Moore-Willson Napoleon Bonaparte Broward Frederick S. Morse James Milton Carson Mary Barr Munroe Ernest F. Coe Ralph Middleton Munroe Barron G. Collier Ruth Bryan Owen Marjory Stoneman Douglas John Kunkel Small David Fairchild Frank Stranahan Ion Farris Ivy Julia Cromartie Stranahan http://everglades.fiu.edu/reclaim/bios/index.htm[10/1/2014 2:16:58 PM] Everglades Digital Library Henry Flagler James Mallory Willson Duncan Upshaw Fletcher William Sherman Jennings John Clayton Gifford Home | About Us | Browse | Ask an Everglades Librarian | FIU Libraries This site is designed and maintained by the Digital Collections Center - [email protected] Everglades Information Network & Digital Library at Florida International University Libraries Copyright © Florida International University Libraries. All rights reserved. http://everglades.fiu.edu/reclaim/bios/index.htm[10/1/2014 2:16:58 PM] Everglades Digital Library Guide to Collection Everglades Timeline Everglades Biographies Everglades Biographies Bowman Foster Ashe Research Help Bowman Foster Ashe, a native of Scottsdale, Pennsylvania, came to Miami in Everglades Librarian 1926 to be involved with the foundation of the University of Miami. Dr. Ashe graduated from the University of Pittsburgh and held honorary degrees from the Ordering Reproductions University of Pittsburgh, Stetson University, Florida Southern College and Mount Union College. -

Wilderness on the Edge: a History of Everglades National Park

Wilderness on the Edge: A History of Everglades National Park Robert W Blythe Chicago, Illinois 2017 Prepared under the National Park Service/Organization of American Historians cooperative agreement Table of Contents List of Figures iii Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in Footnotes xv Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s 1 Chapter 2: Early Conservation Efforts in the Everglades 40 Chapter 3: The Movement for a National Park in the Everglades 62 Chapter 4: The Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment 92 Chapter 5: First a Wildlife Refuge, Then a National Park 131 Chapter 6: Land Acquisition 150 Chapter 7: Developing the Park 176 Chapter 8: The Water Needs of a Wetland Park: From Establishment (1947) to Congress’s Water Guarantee (1970) 213 Chapter 9: Water Issues, 1970 to 1992: The Rise of Environmentalism and the Path to the Restudy of the C&SF Project 237 Chapter 10: Wilderness Values and Wilderness Designations 270 Chapter 11: Park Science 288 Chapter 12: Wildlife, Native Plants, and Endangered Species 309 Chapter 13: Marine Fisheries, Fisheries Management, and Florida Bay 353 Chapter 14: Control of Invasive Species and Native Pests 373 Chapter 15: Wildland Fire 398 Chapter 16: Hurricanes and Storms 416 Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources 430 Chapter 18: Museum Collection and Library 449 Chapter 19: Relationships with Cultural Communities 466 Chapter 20: Interpretive and Educational Programs 492 Chapter 21: Resource and Visitor Protection 526 Chapter 22: Relationships with the Military -

Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources

Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources Everglades National Park was created primarily because of its unique flora and fauna. In the 1920s and 1930s there was some limited understanding that the park might contain significant prehistoric archeological resources, but the area had not been comprehensively surveyed. After establishment, the park’s first superintendent and the NPS regional archeologist were surprised at the number and potential importance of archeological sites. NPS investigations of the park’s archeological resources began in 1949. They continued off and on until a more comprehensive three-year survey was conducted by the NPS Southeast Archeological Center (SEAC) in the early 1980s. The park had few structures from the historic period in 1947, and none was considered of any historical significance. Although the NPS recognized the importance of the work of the Florida Federation of Women’s Clubs in establishing and maintaining Royal Palm State Park, it saw no reason to preserve any physical reminders of that work. Archeological Investigations in Everglades National Park The archeological riches of the Ten Thousand Islands area were hinted at by Ber- nard Romans, a British engineer who surveyed the Florida coast in the 1770s. Romans noted: [W]e meet with innumerable small islands and several fresh streams: the land in general is drowned mangrove swamp. On the banks of these streams we meet with some hills of rich soil, and on every one of those the evident marks of their having formerly been cultivated by the savages.812 Little additional information on sites of aboriginal occupation was available until the late nineteenth century when South Florida became more accessible and better known to outsiders. -

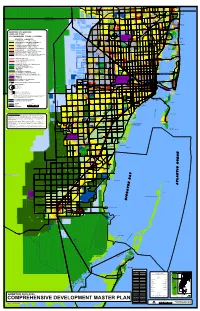

Comprehensive Development Master Plan (CDMP) and Are NAPPER CREEK EXT Delineated in the Adopted Text

E E E A I E E E E E V 1 E V X D 5 V V V V I I V A Y V A 9 A S A A A D E R A 7 I A W 7 2 U 7 7 2 K 7 O 3 7 H W 7 4 5 6 P E W L 7 E 9 W T W N F V W E V 7 W N W N W A W N V 2 A N N 5 N N 7 A 7 S 7 0 1 7 I U 1 1 8 W S DAIRY RD GOLDEN BEACH W SNAKE CREEK CANAL IVE W N N N NW 202 ST AVENTURA BROWARD COUNTY MAN C LEH SWY OMPIAA-MLOI- C K A MIAMI-DADE COUNTY DAWDEES T CAOIRUPNOTYR T NW 186 ST MIAMI GARDENS SUNNY ISLES BEACH E K P T ST W A NE 167 NORTH MIAMI BEACH D NW 170 ST O I NE 163 ST K R SR 826 EXT E E E O OLETA RIVER E V C L V STATE PARK A A H F 0 O 2 1 B 1 ADOPTED 2015 AND 2025 E E E T E N R X N D E LAND USE PLAN * NW 154 ST 9 R Y FIU/BUENA MIAMI LAKES S W VISTA H 1 FOR MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA OPA-LOCKA E AIRPORT I S HAULOVER X U I PARK D RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITIES NW 138 ST OPA-LOCKA W ESTATE DENSITY (EDR) 1-2.5 DU/AC G ESTATE DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) R NORTH MIAMI BAL HARBOUR A T BR LOW DENSITY (LDR) 2.5-6 DU/AC IG OAD N BAY HARBOR ISLANDS HIALEAH GARDENS Y CSW LOW DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) Y AMELIA EARHART PKY E PARK E V E E BISCAYNE PARK E V LOW-MEDIUM DENSITY (LMDR) 6-13 DU/AC V A V V V A D I A A A SURFSIDE MDOC A V 7 M LOW-MEDIUM DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) 2 L 2 7 NORTH 2 1 A B INDIAN CREEK VILLAGE I 2 E E W W E E M W V MEDIUM DENSITY (MDR) 13-25 DU/AC N N N W N V N A N Y NW 106 ST N A 6 MEDIUM DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) A HIALEAH C S E IS N MEDIUM-HIGH DENSITY (MHDR) 25-60 DU/AC N B I MEDLEY L L HIGH DENSITY (HDR) 60-125 DU/AC OR MORE/GROSS AC E MIAMI SHORES O V E C A TWO DENSITY -

Vegetation Trends in Indicator Regions of Everglades National Park Jennifer H

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons GIS Center GIS Center 5-4-2015 Vegetation Trends in Indicator Regions of Everglades National Park Jennifer H. Richards Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, [email protected] Daniel Gann GIS-RS Center, Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/gis Recommended Citation Richards, Jennifer H. and Gann, Daniel, "Vegetation Trends in Indicator Regions of Everglades National Park" (2015). GIS Center. 29. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/gis/29 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the GIS Center at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GIS Center by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Final Report for VEGETATION TRENDS IN INDICATOR REGIONS OF EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK Task Agreement No. P12AC50201 Cooperative Agreement No. H5000-06-0104 Host University No. H5000-10-5040 Date of Report: Feb. 12, 2015 Principle Investigator: Jennifer H. Richards Dept. of Biological Sciences Florida International University Miami, FL 33199 305-348-3102 (phone), 305-348-1986 (FAX) [email protected] (e-mail) Co-Principle Investigator: Daniel Gann FIU GIS/RS Center Florida International University Miami, FL 33199 305-348-1971 (phone), 305-348-6445 (FAX) [email protected] (e-mail) Park Representative: Jimi Sadle, Botanist Everglades National Park 40001 SR 9336 Homestead, FL 33030 305-242-7806 (phone), 305-242-7836 (Fax) FIU Administrative Contact: Susie Escorcia Division of Sponsored Research 11200 SW 8th St. – MARC 430 Miami, FL 33199 305-348-2494 (phone), 305-348-6087 (FAX) 2 Table of Contents Overview ............................................................................................................................ -

Natural, Cultural & Agricultural Resources January 21,, 2010

Sawyer County Comprehensive Plan – Natural, Cultural & Agricultural Resources January 21, 2010 Natural, Cultural & Agricultural Resources Wisconsin State Statute 66.1001(2)(e) Agricultural, Natural & Cultural Resources A compilation of objectives, policies, goals, maps and programs for the conservation, and promotion of the effective management, of natural resources such as groundwater, forests, productive agricultural areas, environmentally sensitive areas, threatened and endangered species, stream corridors, surface water, floodplains, wetlands, wildlife habitat, metallic and nonmetallic mineral resources consistent with zoning limitations under s.295.20(2), parks, open spaces, historical and cultural resources, community design, recreational resources and other natural resources. INTRODUCTION The protection of natural resources is necessary for the welfare of both people and the environment. By allowing natural processes, such as the hydrologic system, to function without impediment, property, water supply and the environment are protected. The protection of natural resources also preserves important ecological communities. Certain natural resources have more than merely aesthetic and leisure‐time activity values. They are essential to long‐term human survival and the preservation of life, health and general welfare. As such, the protection and management of these resources clearly are in the public interest. Thus, the analysis of those natural resources found within the planning area is done for the purpose of directing development away from those areas not intrinsically suitable for a particular use, or to at least guide development in a direction that is least disruptive. TOPOGRAPHY An undulating plain dissected by many lakes, rivers and streams characterizes the topography of Sawyer County. The northeastern corner of the County is quite hilly and the southwestern corner contains many high quartzite ridges. -

Recommended Minimum Flows for the Lower Peace River and Proposed Minimum Flows Lower Shell Creek, Draft Report

Recommended Minimum Flows for the Lower Peace River and Proposed Minimum Flows Lower Shell Creek, Draft Report November 30, 2020 Recommended Minimum Flows for the Lower Peace River and Proposed Minimum Flows for Lower Shell Creek, Draft Report November 30, 2020 Yonas Ghile, PhD, PH, Lead Hydrologist XinJian Chen, PhD, PE, Chief Professional Engineer Douglas A. Leeper, MFLs Program Lead Chris Anastasiou, PhD, Chief Water Quality Scientist Kristina Deak, PhD, Staff Environmental Scientist Southwest Florida Water Management District 2379 Broad Street Brooksville, Florida 34604-6899 The Southwest Florida Water Management District (District) does not discriminate on the basis of disability. This nondiscrimination policy involves every aspect of the District’s functions, including access to and participation in the District’s programs, services, and activities. Anyone requiring reasonable accommodation, or who would like information as to the existence and location of accessible services, activities, and facilities, as provided for in the Americans with Disabilities Act, should contact Donna Eisenbeis, Sr. Performance Management Professional, at 2379 Broad St., Brooksville, FL 34604-6899; telephone (352) 796-7211 or 1-800- 423-1476 (FL only), ext. 4706; or email [email protected]. If you are hearing or speech impaired, please contact the agency using the Florida Relay Service, 1-800-955-8771 (TDD) or 1-800-955-8770 (Voice). If requested, appropriate auxiliary aids and services will be provided at any public meeting, forum, or event of the District. In the event of a complaint, please follow the grievance procedure located at WaterMatters.org/ADA. i Table of Contents Acronym List Table......................................................................................................... vii Conversion Unit Table .................................................................................................. -

Exhibit Specimen List FLORIDA SUBMERGED the Cretaceous, Paleocene, and Eocene (145 to 34 Million Years Ago) PARADISE ISLAND

Exhibit Specimen List FLORIDA SUBMERGED The Cretaceous, Paleocene, and Eocene (145 to 34 million years ago) FLORIDA FORMATIONS Avon Park Formation, Dolostone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; with echinoid sand dollar fossil (Periarchus lyelli); specimen from Florida Geological Survey Avon Park Formation, Limestone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; with organic layers containing seagrass remains from formation in shallow marine environment; specimen from Florida Geological Survey Ocala Limestone (Upper), Limestone from Eocene time; Jackson County, Florida; with foraminifera; specimen from Florida Geological Survey Ocala Limestone (Lower), Limestone from Eocene time; Citrus County, Florida; specimens from Tanner Collection OTHER Anhydrite, Evaporite from early Cenozoic time; Unknown location, Florida; from subsurface core, showing evaporite sequence, older than Avon Park Formation; specimen from Florida Geological Survey FOSSILS Tethyan Gastropod Fossil, (Velates floridanus); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Barge Canal spoil island, Levy County, Florida; specimen from Tanner Collection Echinoid Sea Biscuit Fossils, (Eupatagus antillarum); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Barge Canal spoil island, Levy County, Florida; specimens from Tanner Collection Echinoid Sea Biscuit Fossils, (Eupatagus antillarum); In Ocala Limestone from Eocene time; Mouth of Withlacoochee River, Levy County, Florida; specimens from John Sacha Collection PARADISE ISLAND The Oligocene (34 to 23 million years ago) FLORIDA FORMATIONS Suwannee -

In Honor of Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Guardian of the Everglades

I I lr4sTIluTEFOn SCientifiC IN f0t7MAT10N@ I 3501 MARKET ST, PHILADELPHIA, PA 191Cd In Honor of Marjory Stoneman Douglas, I Guardian of the Everglades [ Number 33 Auizust 14, 1989 This essay considers the life and work of Marjory Stoneman Douglas (1890- ), an authority on the Florida Everglades whose writings and advocacy have made her one of the most celebrated defenders of that subtropicalregion, Also discussedis a bronze sratue of a Ftorida panther by Philadelphia scufptor Eric Berg, which ISI@ has commissioned for installation in the Everglades NationaI Park. Activism on behalf of the environment, tually, we visited the Everglades National at least on a broad scale, seems a relatively Park together, where I purchased her books. recent phenomenon. The late- 1960s’ ‘‘ecol- I then asked Len to arrange a meeting with ogy” movement, which probably reached his old tilend. The three of us met at her its height with the observance of Earth Day home in Coconut Grove last summer. in 1970, gave rise to a new popular con- When I spoke with this remarkable wom- sciousness of environmental issues. While an, she shared many insights into her own this consciousness may have waned at times life, the problems facing the Everglades and in succeeding years, there is no doubt that surrounding areas, education, politics, and in the late 1980s, with headlines being made a host of other topics. In tits essay, in honor by oil spills, toxic waste, polluted beaches, of Douglas, I’d like to describe briefly some- disappearing rain forests, and the green- thing of her life and work, present a few ex- house effect, concern for the environment cerpts from our conversation, and discuss has returned to the forefront as an intern- one small way in which ISI@ is helping to ational priority. -

Collier Miami-Dade Palm Beach Hendry Broward Glades St

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission F L O R ID A 'S T U R N P IK E er iv R ee m Lakewood Park m !( si is O K L D INDRIO ROAD INDRIO RD D H I N COUNTY BCHS Y X I L A I E O W L H H O W G Y R I D H UCIE BLVD ST L / S FT PRCE ILT SRA N [h G Fort Pierce Inlet E 4 F N [h I 8 F AVE "Q" [h [h A K A V R PELICAN YACHT CLUB D E . FORT PIERCE CITY MARINA [h NGE AVE . OKEECHOBEE RA D O KISSIMMEE RIVER PUA NE 224 ST / CR 68 D R !( A D Fort Pierce E RD. OS O H PIC R V R T I L A N N A M T E W S H N T A E 3 O 9 K C A R-6 A 8 O / 1 N K 0 N C 6 W C W R 6 - HICKORY HAMMOCK WMA - K O R S 1 R L S 6 R N A E 0 E Lake T B P U Y H D A K D R is R /NW 160TH E si 68 ST. O m R H C A me MIDWAY RD. e D Ri Jernigans Pond Palm Lake FMA ver HUTCHINSON ISL . O VE S A t C . T I IA EASY S N E N L I u D A N.E. 120 ST G c I N R i A I e D South N U R V R S R iv I 9 I V 8 FLOR e V ESTA DR r E ST. -

University of Michigan Radiocarbon Dates Xii H

[Ru)Ioc!RBo1, Vol.. 10, 1968, P. 61-114] UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN RADIOCARBON DATES XII H. R. CRANE and JAMES B. GRIFFIN The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan The following is a list of dates obtained since the compilation of List XI in December 1965. The method is essentially the same as de- scribed in that list. Two C02-CS2 Geiger counter systems were used. Equipment and counting techniques have been described elsewhere (Crane, 1961). Dates and estimates of error in this list follow the practice recommended by the International Radiocarbon Dating Conferences of 1962 and 1965, in that (a) dates are computed on the basis of the Libby half-life, 5570 yr, (b) A.D. 1950 is used as the zero of the age scale, and (c) the errors quoted are the standard deviations obtained from the numbers of counts only. In previous Michigan date lists up to and in- cluding VII, we have quoted errors at least twice as great as the statisti- cal errors of counting, to take account of other errors in the over-all process. If the reader wishes to obtain a standard deviation figure which will allow ample room for the many sources of error in the dating process, we suggest doubling the figures that are given in this list. We wish to acknowledge the help of Patricia Dahlstrom in pre- paring chemical samples and David M. Griffin and Linda B. Halsey in preparing the descriptions. I. GEOLOGIC SAMPLES 9240 ± 1000 M-1291. Hosterman's Pit, Pennsylvania 7290 B.C. Charcoal from Hosterman's Pit (40° 53' 34" N Lat, 77° 26' 22" W Long), Centre Co., Pennsylvania.