Washington Journal of Modern China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12';I. ,Ft ,{Il No

12';i. ,ft ,{il No. 6 February 9, 1970 BEIJI Vice-Premier Deng in Washington $ China's Minority Peoples a*'-15-- BEIJING REVIEW CTilRONNCN,E ih a A.fu Jan. 2E Xinhua News Agency reports that the C.P.C. VoL t2, No. 6 Februory g, liln Central Committee recently passed a "Decision on the Question of .Removing the Designations of Landlords and Rich Peasants and on the Class Status of the Children of Landlords and Rich CONIENTS Peasants.;' The decision points out that, except those who persist in maintaining their reac- CHRONICLE tionary stand, all landlords, rich peasants, eounter-revolutionaries and bad elements who, over EVENTS E IRENDS the years; have obs.erved government laws and decrees a4d who have worked honestly, shall"be con- Vice-Premier Deng Visits the Uniied Stotcs sidered as members of rural Beople's communes. All Longings for Kinsfolk members of rural people's communes whose class ' Commission for lnspection of Dlsciplinc origin is that of landlord or rich peasant shalL have Meets the class status of commune member and the class member Fewer Bobies Born Lost Yeor origin of their children shall be commune and no longer that of landlord or rich peasant. In Thirteen Veteron Codres Rehobilitoted urban areas the above also applies. ARTICLES AND DOCUMENTS Jan. 3l Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping and President Vice-Premier Deng in Woshington Carter sign a scien.tific and technological co- New Poge Annols Sino-Americon in of operation agreement and a cultural agreement. Relotions Vice-Premier Deng Xioo- - ping's vish to the United Stotes-Yugn Feb. -

Download Transcript

Getting Real NOW: Documenting Press Freedom & Impact - Transcript Cassidy Dimon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to our panel. We're going to take a couple minutes here and let the room populate before we begin. Just hold tight. Thank you. Hello all. Again thank you for joining. I see a lot of you have joined recently. We're going to take just two more minutes here and let people get into the room. And we will get started at approximately 5:03. Thank you. Carrie Lozano: Good evening, everyone. I know some of you are still joining us tonight. But I'm so happy to kick off this conversation. I honestly can't imagine anywhere else I'd rather be right now. So thank you for joining us for this second installment of Getting Real Now. My name is Carrie Lozano. I am the director of IDA's Enterprise Documentary Fund. I would like to acknowledge that I am in northern California on Ohlone land. And as many of you might know, we are encircled by fire and smoke throughout the west coast. And I am just reminded that in Native tradition, it's the Earth's way of renewing its soil and making it fertile to burn. And while it might be uncomfortable for us, it's the planet's way of healing itself. And so I hope we can all hold space together and honor all that the planet is doing to correct itself. Before I introduce our speakers, I really want to thank all of the sponsors and supporters that make these conversations and getting real in the digital space possible. -

Winthrop Students Win Prizes in C-SPAN Video Documentary Competition

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: WEDNESDAY, MARCH 10, 2021 Winthrop Students Win Prizes in C-SPAN Video Documentary Competition During unprecedented times, students addressed issues of national importance WASHINGTON (March 10, 2021) – Today C-SPAN announced that students in Winthrop, Iowa, are winners in C-SPAN’s national 2021 StudentCam competition. The following students from East Buchanan Community School have won prizes: Trey Johnson, Tristan Lau and Cole Bowden will receive $250 as honorable mention winners for the documentary, "Government Subsidies for Electric Vehicles." Keira Hellenthal , Hannah McMurrin and Emma Kress will receive $250 as honorable mention winners for the documentary, "Our Future Reality," about the environment and changing climate. The competition, now in its 17th year, invited all middle and high school students to enter by producing a short documentary. C-SPAN, in cooperation with cable television partners, asked students to join the national conversation on the challenges our country is facing with the theme: "Explore the issue you most want the president and new Congress to address in 2021." Despite the unique challenges brought about by COVID-19 this year, more than 2,300 students across the country participated in the contest. C-SPAN received over 1,200 entries from 43 states and Washington, D.C. The most popular topics addressed were: Health Care (14.9%) Environmental and Energy Policy (14.6%) Equal Rights and Equity (13.5%) Criminal Justice/Policing (7.6%) Education (7.5%) "With the continual shift in the educational landscape, it is difficult to overstate just how challenging the pandemic has proven for schools across our nation," said Craig McAndrew, Director, C-SPAN Education Relations. -

Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #Metoo

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 49 Issue 1 Article 3 2019 Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #MeToo Nicole Hallett University of Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hallett, Nicole (2019) "Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #MeToo," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 49 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol49/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMMIGRANT WOMEN IN THE SHADOW OF #METOO Nicole Hallett* I. INTRODUCTION We hear Daniela Contreras’s voice, but we do not see her face in the video in which she recounts being raped by an employer at the age of sixteen.1 In the video, one of four released by a #MeToo advocacy group, Daniela speaks in Spanish about the power dynamic that led her to remain silent about her rape: I couldn’t believe that a man would go after a little girl. That a man would take advantage because he knew I wouldn’t say a word because I couldn’t speak the language. Because he knew I needed the money. Because he felt like he had the power. And that is why I kept quiet.2 Daniela’s story is unusual, not because she is an undocumented immigrant who was victimized -

Public Service, Private Media: the Political Economy of The

PUBLIC SERVICE, PRIVATE MEDIA: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE CABLE-SATELLITE PUBLIC AFFAIRS NETWORK (C-SPAN) by GLENN MICHAEL MORRIS A DISSERTATION Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2010 11 University of Oregon Graduate School Confirmation ofApproval and Acceptance of Dissertation prepared by: Glenn Morris Title: "Public Service, Private Media: The Political Economy ofthe Cable-Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN)." This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree in the Department of Journalism and Communication by: Janet Wasko, Chairperson, Journalism and Communication Carl Bybee, Member, Journalism and Communication Gabriela Martinez, Member, Journalism and Communication John Foster, Outside Member, Sociology and Richard Linton, Vice President for Research and Graduate Studies/Dean ofthe Graduate School for the University of Oregon. June 14,2010 Original approval signatures are on file with the Graduate School and the University of Oregon Libraries. 111 © 2010 Glenn Michael Morris IV An Abstract of the Dissertation of Glenn Michael Morris for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism and Communication to be taken June 2010 Title: PUBLIC SERVICE, PRIVATE MEDIA: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE CABLE-SATELLITE PUBLIC AFFAIRS NETWORK (C-SPAN) Approved: _ Dr. Janet Wasko The Satellite-Cable Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN) is the only television outlet in the U.S. providing Congressional coverage. Scholars have studied the network's public affairs content and unedited "gavel-to-gavel" style of production that distinguish it from other television channels. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

Greta Thunberg: the Voice of Our Planet

Berkeley Leadership Case Series 21-180-017 February 16, 2021 1 Greta Thunberg: The Voice of Our Planet “Over 1,000 students and adults sit alongside Greta on the last day of the school strike. Media and news reporters from several different countries gather around the crowd at Mynttorget Square. Many people believe she has achieved more for the climate than most politicians and the mass media has done in years. But Greta seems to disagree. “Nothing has changed,” she says. “The emissions continue to increase and there is no change in sight.” - Malena Ernman (Greta Thunberg’s mother) i At the age of 17, Greta Thunberg is one of the most powerful voices in the global movement addressing Earth’s climate crisis. Thunberg has successfully stepped up to create a call to action, reached a massive audience, and rallied support across multiple nations. Her activism and sudden rise to the world stage has earned her numerous honors as the youngest Time Person of the Year and two-time Nobel Peace Prize nominee. “The Greta Thunberg Effect”, as journalists have dubbed it, has compelled politicians and government officials to focus on climate change. Despite her accolades, however, Thunberg believes there remains much to do before the planet is truly safe and healthy. “Our house is still on fire,” she warned earlier this year. Going forward, how can Thunberg scale her movement to deliver substantive policy change? The Problem of Climate Change Since the mid-20th century, scientists and researchers have attributed the exponential increase in global temperature (see Exhibit 1) to an increase in human activity. -

C-Span Announces Winners of 2020 Studentcam Documentary Competition

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: WEDNESDAY, MARCH 11, 2020 C-SPAN ANNOUNCES WINNERS OF 2020 STUDENTCAM DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION Students explore issues of national importance in the 2020 presidential campaign Jason Lin, Amar Karoshi and Sara Yen receive $5,000 for their Grand Prize documentary, “Cmd-Delete: Technology's Damaging Effect on Democracy in 2020.” WASHINGTON (March 11, 2020) – C-SPAN announced the winners of the national 2020 StudentCam documentary competition, awarding a total of $100,000 in cash prizes to 150 winning documentaries. Each year since 2006, C-SPAN partners with local cable television providers in communities nationwide to invite middle and high school students to produce short documentaries about a subject of national importance. This year students addressed the theme, "What's Your Vision in 2020? Explore the issue you most want presidential candidates to address during the campaign." In response, nearly 5,400 students from 44 states and Washington, D.C., participated. C-SPAN received over 2,500 submissions on a variety of topics. The most popular topics addressed were: • Environment (18%) – Climate Change, Green New Deal, Pollution and Plastics • Equality/Discrimination (15%) – Prison Rights, Affirmative Action, Veterans' Rights, Human Rights • Guns (13%) – Gun Control, Mass Shootings, Second Amendment, Gun Safety • Health Care (12%) – Universal Health Care, Mental Health, Addictions, Vaping • Immigration (9%) – Border Security, Undocumented Immigration, Separation of Families, DACA "StudentCam provides a platform for young people to have their voices heard on the issues they are clearly passionate about," said C-SPAN's Director of Education Relations Craig McAndrew. "This year's entries reflect remarkable research and production values and feature a wide range of interviews with elected officials and experts. -

Spring Taps 2020

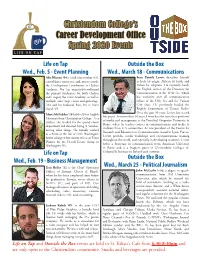

Christendom College’College’ss CarCareereer Development Office Spring 2020 Events Life on Tap Outside the Box Wed., Feb. 5 - Event Planning Wed., March 18 - Communications Alex Klassen ‘04 is a full time mother of 6, Sean Patrick Lovett describes himself retired dance instructor, and, most recently, as Irish by origin, African by birth, and the Development Coordinator at Chelsea Italian by adoption. He currently heads Academy. She has organized/coordinated the English section of the Dicastery for the primary fundraisers for both Chelsea Communication of the Holy See, which and Gregory the Great Academy, as well as has authority over all communication multiple other large events and gatherings. offices of the Holy See and the Vatican Alex and her husband, Ron, live in Front City State. He previously headed the Royal, VA. English Department of Vatican Radio. Over the past 40 years, Lovett has served Maria McFadden ‘18 holds a BA in English five popes. For more than 30 years, Lovett has also served as a professor Literature from Christendom College. As a of media and management at the Pontifical Gregorian University in student, she worked for the special events Rome, where he teaches courses in communications and media to department and directed Swing ‘n Sundaes, students from U.S. universities. As vice president of the Centre for among other things. She initially worked Research and Education in Communication, based in Lyon, France, as a florist at the Inn at Little Washington Lovett provides media workshops and communications training before taking on her current role as an Event throughout the world, and especially in developing countries. -

Last Name First Name Abrams Stacey Adichie Chimamanda Albright

Last Name First Name Identifying Information Former Minority Leader of the Georgia State House of Representatives (2011-2017) and Democratic candidate for Governor of Georgia and author of "Minority Abrams Stacey Leader: How to Lead from the Outside and Make Real Change" (2018) Adichie Chimamanda Novelist/writer MacArthur “genius” Fellowship & Women’s prize for fiction 2012 Ted Talk "We Should All Be Feminists" American politician and diplomat. She is the first female United States Secretary of State in U.S. history, having served from 1997 to 2001 under President Bill Albright Madeline Clinton Anthony Carmelo Played for SU one year, winning national championship, NBA star, Philanthropist Atwood Margaret Canadian poet, novelism teacher and enviornmental activist. Biden Joseph Syracuse Law School graduate. Previous Vice President of the United States Boeheim Jim SU Alum, SU Men's Basketball Head Coach, former SU basketball player A research professor at the University of Houston where she holds the Huffington Foundation – Brené Brown Endowed Chair at The Graduate College of Social Brown Dr. Brené Work. Burke Tarana founder of the "Me Too Movement" and the organization Just Be Inc. Girls for Gender Equity; advocate against sexual assault and harassment Burnie Burns Technology/Media Entrepreneur. Created successful 21st century media company (rooster teeth) by bridging gap between technology and liberal arts. George Walker Bush is an American politician who served as the 43rd President of the United States from 2001 to 2009. He was also the 46th Governor of Texas Bush George W. from 1995 to 2000. Chopra Deepak Author, Alternative Medicine Advocate Colbert Stephen CBS Late Show host, American political satirist, writer, producer. -

Social Movements 1965-1975

Turn Turn Turn social movements 1965–75 March 26–November 6, 2011 contact:Jennifer Reynolds, media specialist, 909-307-2669 ext. 278 Michele Nielsen, curator of history, 909-307-2669 ext. 240 Power to the people social and political movements And three people do it, three, can you imagine, three people walking in [to the draft board] singin’ a bar of Alice’s Restaurant and walking out. They may think it’s an organization. And can you, can you imagine fifty people a day, I said fifty people a day walking in singin’ a bar of Alice’s Restaurant and walking out. And friends, they may think it’s a movement. —Arlo Guthrie, “Alice’s Restaurant,” ©1966 1965 • Time Magazine calls young people a “generation of conformists” • Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) organizes first teach-in to protest US involvement in the Vietnam War at the University of Michigan; 3000 people participate. • SDS leads the first anti-Vietnam War march in Washington. 25,000 attend including Phil Ochs, Joan Baez and Judy Collins 909-307-2669 • www.sbcountymuseum.org 2024 Orange Tree Lane, Redlands CA 92374 • Martin Luther King Jr. and 770 other protesters are arrested in Selma, Alabama while picketing the county courthouse to end discriminatory voting rights. • The first public burning of a draft card occurs in protest of the Vietnam War. It is coordinated by the student National Coordinating Committee to End the War in Vietnam. 1966 • Soon after taking charge at SNCC (Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee), Stokely Carmichael rejects nonviolence and invokes “Black Power.” • The National Organization for Women (NOW) is founded to bring women “into full participation in the mainstream of American society.” Betty Friedan becomes its first president. -

Lawyers for #Ustoo: an Analysis of the Challenges Posed by the Contingent Fee System in Tort Cases for Sexual Assault

LAWYERS FOR #USTOO: AN ANALYSIS OF THE CHALLENGES POSED BY THE CONTINGENT FEE SYSTEM IN TORT CASES FOR SEXUAL ASSAULT Christine Rua* ABSTRACT According to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, one in five women will be raped at some point in their lives, and one in three women will experience some form of sexual violence. Despite the widespread prevalence of sexual assault, it is the country’s most under- reported crime. These illustrative statistics are alarming and suggest that current criminal law approaches to the sexual assault epidemic are inadequate, both in meeting the needs of survivors and in holding perpetrators accountable. These inadequacies have the potential to become even more widely experienced in light of movements like #MeToo, given that survivors may now be more willing to come forward, seek support, and engage with the legal system. Given these realities, scholars have begun to explore alternatives to criminal prosecutions for sexual assault, and many have identified tort law as a potential alternative path. However, tort law is generally underused, despite its potential to provide sexual assault survivors with a variety of benefits. This Note aims to provide a structural explanation for why more sexual assault claims are not successfully pursued in tort. Specifically, this Note explores how the contingent fee system and tort reform may affect the frequency and type of sexual assault cases plaintiff-side lawyers are willing to accept and bring to trial. This Note draws on both quantitative data and informal attorney interviews to demonstrate how tort reform statutes influence attorney decisionmaking in sexual assault cases, and how attorney screening decisions in the aggregate may foreclose legal recourse for survivors in * J.D.