MAKING Shiff 1. Essex Record Office

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Services to Chelmsford 2020/21 Routes: 510 Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Steeple - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford

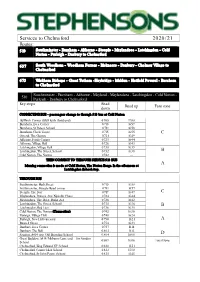

Services to Chelmsford 2020/21 Routes: 510 Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Steeple - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford 637 South Woodham - Woodham Ferrers - Bicknacre - Danbury - Chelmer Village to Chelmsford 673 Wickham Bishops - Great Totham -Heybridge - Maldon - Hatfield Peverel - Boreham to Chelmsford Southminster - Burnham - Althorne - Mayland - Maylandsea - Latchingdon - Cold Norton - 510 Purleigh - Danbury to Chelmsford Key stops Read Read up Fare zone down CONNECTING BUS - passengers change to through 510 bus at Cold Norton Bullfinch Corner (Old Heath Road end) 0708 1700 Burnham, Eves Corner 0710 1659 Burnham, St Peters School 0711 1658 Burnham, Clock Tower 0715 1655 C Ostend, The George 0721 1649 Althorne, Fords Corner 0725 1644 Althorne, Village Hall 0726 1643 Latchingdon, Village Hall 0730 1639 Latchingdon, The Street, School 0732 1638 B Cold Norton, The Norton 0742 -- THEN CONNECT TO THROUGH SERVICE 510 BUS A Morning connection is made at Cold Norton, The Norton Barge. In the afternoon at Latchingdon School stop. THROUGH BUS Southminster, High Street 0710 1658 Southminster, Steeple Road corner 0711 1657 Steeple, The Star 0719 1649 C Maylandsea, Princes Ave/Nipsells Chase 0724 1644 Maylandsea, The Drive, Drake Ave 0726 1642 Latchingdon, The Street, School 0735 1636 B Latchingdon, Red Lion 0736 1635 Cold Norton, The Norton (Connection) 0742 1630 Purleigh, Village Hall 0748 1624 Purleigh, New Hall vineyard 0750 1621 A Runsell Green 0754 1623 Danbury, Eves Corner 0757 1618 Danbury, The -

Research Framework Revised.Vp

Frontispiece: the Norfolk Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment Survey team recording timbers and ballast from the wreck of The Sheraton on Hunstanton beach, with Hunstanton cliffs and lighthouse in the background. Photo: David Robertson, copyright NAU Archaeology Research and Archaeology Revisited: a revised framework for the East of England edited by Maria Medlycott East Anglian Archaeology Occasional Paper No.24, 2011 ALGAO East of England EAST ANGLIAN ARCHAEOLOGY OCCASIONAL PAPER NO.24 Published by Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers East of England http://www.algao.org.uk/cttees/Regions Editor: David Gurney EAA Managing Editor: Jenny Glazebrook Editorial Board: Brian Ayers, Director, The Butrint Foundation Owen Bedwin, Head of Historic Environment, Essex County Council Stewart Bryant, Head of Historic Environment, Hertfordshire County Council Will Fletcher, English Heritage Kasia Gdaniec, Historic Environment, Cambridgeshire County Council David Gurney, Historic Environment Manager, Norfolk County Council Debbie Priddy, English Heritage Adrian Tindall, Archaeological Consultant Keith Wade, Archaeological Service Manager, Suffolk County Council Set in Times Roman by Jenny Glazebrook using Corel Ventura™ Printed by Henry Ling Limited, The Dorset Press © ALGAO East of England ISBN 978 0 9510695 6 1 This Research Framework was published with the aid of funding from English Heritage East Anglian Archaeology was established in 1975 by the Scole Committee for Archaeology in East Anglia. The scope of the series expanded to include all six eastern counties and responsi- bility for publication passed in 2002 to the Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers, East of England (ALGAO East). Cover illustration: The excavation of prehistoric burial monuments at Hanson’s Needingworth Quarry at Over, Cambridgeshire, by Cambridge Archaeological Unit in 2008. -

Evolve Launch Brochure (Colchester)

FIND YOUR SPACE COLCHESTER starting Evolve is a new concept in flexible, affordable, self owned and operated workspace - designed for both start-up and investment. Consider the facts: I can own my own freehold commercial property*. † There’s zero stamp duty and zero business rates . I’d have all the advantages of placing the property in a SIPP. I could receive mortgage interest tax relief. I’d be operating in a prime location close to all town centre amenities. I could decide to invest in one or more units and enjoy superb projected rental returns. up my business RELOCATING OR OPENING A SATELLITE BRANCH So what do I get... ‘ A brand new split level ‘ready to go’ unit from 395 sqft up to 1358 sqft. In short, your business will Fully connected service including high have everything it needs to speed internet (1 GBPS line). operate under a professional identity in a A free parking bay with additional on-site visitor parking. new small business community with a respected business park address... Full use of on-site private gymnasium and shower facilities. ‘ Full use of meeting suite. we simply Evolve Break out and refreshment facilities. around you * Tenure is 999 year leasehold (virtual freehold). † Subject to being the owner’s sole commercial premises with a rateable value less than £12,000. BURY-ST-EDMUNDS CAMBRIDGE HAVERHILL IPSWICH 9 SUDBURY 33 FELIXSTOWE 29 A120 Evolve Colchester is situated immediately Stansted Airport HARWICH adjacent to the A12 and lies within 2 minutes drive of Junction 29 (A12/A120). BISHOP’S BRAINTREE 25 A120 STORTFORD 8/A COLCHESTER This primary north/south artery connects to the M25 (J28) in 40 minutes or travelling north M11 CLACTON-ON-SEA to Ipswich in just 24 minutes drive time. -

Ardleigh Parish Council

ARDLEIGH PARISH COUNCIL To: Members of Ardleigh Parish Council You are hereby summoned to attend the Meeting of Ardleigh Parish Council to be held on Monday 08 March 2021 by remote Zoom link commencing at 7.30pm for the purpose of transacting the business as set out in the Agenda. Rachel Fletcher - Clerk Dated 3 March 2021 Rachel Fletcher Link to join the Zoom Meeting via internet https://us02web.zoom.us/j/86367365324?pwd=RzhCTlFkS1BZdE5sQWVudmxUVG1VUT09 Meeting ID: 863 6736 5324 Passcode: 293004 Members of the public wishing to attend by telephone should contact the Clerk [email protected] 21.039 Chair’s welcome and outline of proceedings on Zoom 21.040 Apologies and reasons for absence 21.041 Public participation session relating to items on the agenda or other matters of mutual interest There will be 15 minutes available for question time, if required. At the close of this item members of the public will no longer be permitted to address the Council. 21.042 Declaration of Interests To receive declaration of any pecuniary or non-pecuniary interests relating to agenda items. 21.043 Minutes of the last meeting of the Council held on 15 February 2021 To agree the minutes of the last meeting as a true and accurate record (see attachment). 21.044 Planning To comment on the applications published/ received/ validated since the last meeting which cannot be deferred. Applications All applications for consideration can be found on the Tendring District Council web pages https://www.tendringdc.gov.uk/planning/planning-applications and are normally sent to Councillors via the weekly lists provided the Tendring District Council. -

Reading History in Early Modern England

READING HISTORY IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND D. R. WOOLF published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarco´n 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Sabon 10/12pt [vn] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Woolf, D. R. (Daniel R.) Reading History in early modern England / by D. R. Woolf. p. cm. (Cambridge studies in early modern British history) ISBN 0 521 78046 2 (hardback) 1. Great Britain – Historiography. 2. Great Britain – History – Tudors, 1485–1603 – Historiography. 3. Great Britain – History – Stuarts, 1603–1714 – Historiography. 4. Historiography – Great Britain – History – 16th century. 5. Historiography – Great Britain – History – 17th century. 6. Books and reading – England – History – 16th century. 7. Books and reading – England – History – 17th century. 8. History publishing – Great Britain – History. I. Title. II. Series. DA1.W665 2000 941'.007'2 – dc21 00-023593 ISBN 0 521 78046 2 hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page vii Preface xi List of abbreviations and note on the text xv Introduction 1 1 The death of the chronicle 11 2 The contexts and purposes of history reading 79 3 The ownership of historical works 132 4 Borrowing and lending 168 5 Clio unbound and bound 203 6 Marketing history 255 7 Conclusion 318 Appendix A A bookseller’s inventory in history books, ca. -

London Southend Airport Consultation Feedback Report

London Southend Airport Consultation Feedback Report Introduction of New Approach Procedures Issue 1.1 Prepared by: NATS Unmarked London Southend Airport Consultation Feedback Report 2 Table of contents 1. Introduction 5 1.1. Project Overview 5 1.2. Consultation Overview 7 2. Confidentiality 8 3. Stakeholder Engagement 9 3.1. Introduction 9 3.2. National Air Traffic Management Advisory Committee 10 3.3. London Southend Airport Consultative Committee 11 3.4. Local Authorities 13 3.5. National Bodies 16 3.6. MPs 17 3.7. Airspace Users 18 3.8. Others 20 3.9. Members of the Public 20 4. Summary of Consultation Feedback 22 4.1. Stakeholder Invitees 22 4.2. Stakeholder Responses 23 4.3. Responses and Key Themes 24 5. Stakeholder Responses 26 5.1. Key Themes Raised by Stakeholders 26 5.2. Direct Questions Raised & Answers 30 5.3. Concerns Raised & Answers 32 6. Intention to Proceed with the Airspace Change Proposal 35 7. Post-Consultation Steps 37 7.1. Feedback to Stakeholders 37 7.2. Airspace Change Proposal 37 7.3. Post-Implementation Review 37 8. Further Correspondence & Feedback 38 Introduction of New Approach Procedures Page 2 of 40 London Southend Airport Consultation Feedback Report 3 Appendix A 39 Appendix B 40 List of Figures Figure 1 - Image illustrating London Southend CAS (incl. Danger Areas) ............................................ 5 Figure 2 - Image illustrating proposed RNAV routes & CAS .................................................................. 6 Figure 3 - Image illustrating missed approach and Runway 05 transition routes & CAS ................... 7 Figure 4 - Chart showing NATMAC responses...................................................................................... 11 Figure 5 - Chart showing LSACC responses .......................................................................................... 13 Figure 6 - Chart showing Kent Councils responses ............................................................................. -

Appeal Decision

Appeal Decision Inquiry held on 18-21 and 25-27 July 2017 Site visit made on 25 July 2017 by Julia Gregory BSc (Hons), BTP, MRTPI, MCMI an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government Decision date: 06 September 2017 Appeal Ref: APP/Z1510/W/17/3173352 Land off Finchingfield Road, Steeple Bumpstead The appeal is made under section 78 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 against a refusal to grant outline planning permission. The appeal is made by Gladman Developments Ltd against the decision of Braintree District Council. The application Ref 16/01665/OUT, dated 30 September 2016, was refused by notice dated 1 February 2017. The development proposed is the resubmission of application 16/0410/OUT-outline planning permission for up to 65 dwellings (including up to 40% affordable housing), introduction of structural planting and landscaping, informal public open space and children’s play area, surface water flood mitigation and attenuation, vehicular access point from Finchingfield Road, pedestrian access to George Gent Close and associated ancillary works. All matters to be reserved with the exception of the main vehicular site access. Decision 1. The appeal is dismissed. Preliminary matters 2. A linked appeal, reference APP/Z1510/W/16/3157939 in respect of a larger scheme on the same site, was withdrawn on 3 May 2017. 3. The application is in outline with all matters apart from the means of access reserved for future determination. The appellant accepted at the inquiry that the scale on the access plan no A095603-P001 Revision B should be 1:1000 and not 1:500. -

History of the Welles Family in England

HISTORY OFHE T WELLES F AMILY IN E NGLAND; WITH T HEIR DERIVATION IN THIS COUNTRY FROM GOVERNOR THOMAS WELLES, OF CONNECTICUT. By A LBERT WELLES, PRESIDENT O P THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OP HERALDRY AND GENBALOGICAL REGISTRY OP NEW YORK. (ASSISTED B Y H. H. CLEMENTS, ESQ.) BJHttl)n a account of tljt Wu\\t% JFamtlg fn fHassssacIjusrtta, By H ENRY WINTHROP SARGENT, OP B OSTON. BOSTON: P RESS OF JOHN WILSON AND SON. 1874. II )2 < 7-'/ < INTRODUCTION. ^/^Sn i Chronology, so in Genealogy there are certain landmarks. Thus,n i France, to trace back to Charlemagne is the desideratum ; in England, to the Norman Con quest; and in the New England States, to the Puri tans, or first settlement of the country. The origin of but few nations or individuals can be precisely traced or ascertained. " The lapse of ages is inces santly thickening the veil which is spread over remote objects and events. The light becomes fainter as we proceed, the objects more obscure and uncertain, until Time at length spreads her sable mantle over them, and we behold them no more." Its i stated, among the librarians and officers of historical institutions in the Eastern States, that not two per cent of the inquirers succeed in establishing the connection between their ancestors here and the family abroad. Most of the emigrants 2 I NTROD UCTION. fled f rom religious persecution, and, instead of pro mulgating their derivation or history, rather sup pressed all knowledge of it, so that their descendants had no direct traditions. On this account it be comes almost necessary to give the descendants separately of each of the original emigrants to this country, with a general account of the family abroad, as far as it can be learned from history, without trusting too much to tradition, which however is often the only source of information on these matters. -

Windlebrook House Wicken Bonhunt, Saffron Walden, Essex, CB11 3UG Guide Price £835,000 T: 01799 668 600

Windlebrook House Wicken Bonhunt, Saffron Walden, Essex, CB11 3UG Guide Price £835,000 www.arkwrightandco.co.uk T: 01799 668 600 A Deceptively spacious family home in the centre of this popular village with adjoining annex overlooking an area of woodland with a tributary of the River Cam running through the garden of just under half an acre Accommodation Light and airy rooms with a delightful aspect over Windlebrook House was originally built in the early woodland 1970’s and extended in the mid 1980’s. The annexe Large sitting room with open fireplace and triple was converted from the garaging in the 1990’s. The aspect accommodation is well laid out with light and airy Well fitted kitchen with range of modern cabinets, rooms and the added benefit of the adjoining work surface over, fitted Neff ceramic hob and Bosche electric oven and grill, stainless steel sink annexe. There is a large entrance hall with double and drainer, plumbing for dishwasher , plus space doors leading through to the dining room which has for washing machine and dryer a connecting door to the triple aspect sitting room Self-contained annexe with versatile use as part of with its open fireplace. The kitchen/breakfast room the main house or independent is well fitted with modern appliances and a door Delightful garden overlooking a stream and leads through to the boiler room and then the woodland beyond utility room of the annexe. The annexe (currently used as an office) has its own access and with night Location storage heaters comprises a sitting room, kitchen, Windlebrook is situated in the heart of this popular bedroom and wet room. -

South Essex Outline Water Cycle Study Technical Report

South Essex Outline Water Cycle Study Technical Report Final September 2011 Prepared for South Essex: Outline Water Cycle Study Revision Schedule South Essex Water Cycle Study September 2011 Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 01 April 2011 D132233: S. Clare Postlethwaite Carl Pelling Carl Pelling Essex Outline Senior Consultant Principal Consultant Principal Consultant WCS – First Draft_v1 02 August 2011 Final Draft Clare Postlethwaite Rob Sweet Carl Pelling Senior Consultant Senior Consultant Principal Consultant 03 September Final Clare Postlethwaite Rob Sweet Jon Robinson 2011 Senior Consultant Senior Consultant Technical Director URS/Scott Wilson Scott House Alençon Link Basingstoke RG21 7PP Tel 01256 310200 Fax 01256 310201 www.urs-scottwilson.com South Essex Water Cycle Study Limitations URS Scott Wilson Ltd (“URS Scott Wilson”) has prepared this Report for the sole use of Basildon Borough Council, Castle Point Borough Council and Rochford District Council (“Client”) in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by URS Scott Wilson. This Report is confidential and may not be disclosed by the Client or relied upon by any other party without the prior and express written agreement of URS Scott Wilson. The conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others and upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has been requested and that such information is accurate. Information obtained by URS Scott Wilson has not been independently verified by URS Scott Wilson, unless otherwise stated in the Report. -

Essex, Where It Remains to This Day, the Oldest Friends' School in the United Kingdom

The Journal of the Friends Historical Society Volume 60 Number 2 CONTENTS page 75-76 Editorial 77-96 Presidential Address: The Significance of the Tradition: Reflections on the Writing of Quaker History. John Punshon 97-106 A Seventeenth Century Friend on the Bench The Testimony of Elizabeth Walmsley Diana Morrison-Smith 107-112 The Historical Importance of Jordans Meeting House Sue Smithson and Hilary Finder 113-142 Charlotte Fell Smith, Friend, Biographer and Editor W Raymond Powell 143-151 Recent Publications 152 Biographies 153 Errata FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: 2004 John Punshon Clerk: Patricia R Sparks Membership Secretary/ Treasurer: Brian Hawkins Editor of the Journal Howard F. Gregg Annual membership Subscription due 1st January (personal, Meetings and Quaker Institutions in Great Britain and Ireland) raised in 2004 to £12 US $24 and to £20 or $40 for other institutional members. Subscriptions should be paid to Brian Hawkins, Membership Secretary, Friends Historical Society, 12 Purbeck Heights, Belle Vue Road, Swanage, Dorset BH19 2HP. Orders for single numbers and back issues should be sent to FHS c/o the Library, Friends House, 173 Euston Road, London NW1 2BJ. Volume 60 Number 2 2004 (Issued 2005) THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY Communications should be addressed to the Editor of the Journal c/o 6 Kenlay Close, New Earswick, York YO32 4DW, U.K. Reviews: please communicate with the Assistant Editor, David Sox, 20 The Vineyard, Richmond-upon-Thames, Surrey TW10 6AN EDITORIAL The Editor apologises to contributors and readers for the delayed appearance of this issue. Volume 60, No 2 begins with John Punshon's stimulating Presidential Address, exploring the nature of historical inquiry and historical writing, with specific emphasis on Quaker history, and some challenging insights in his text. -

ECC Bus Consultation

Essex County Council ‘Getting Around in Essex’ Local Bus Service Network Review Consultation September 2015 Supporting Documentation 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Proposed broader changes to the way As set out in the accompanying questionnaire, Essex County Council (ECC) is undertaking ECC contracts for services that may also affect a major review of the local bus services in Essex that it pays for. These are the services that are not provided by commercial bus operators. It represents around 15% of the total customers bus network, principally in the evenings, on Sundays and in rural areas although some As well as specific service changes there are a number of other proposals which may do operate in or between towns during weekdays and as school day only services. This affect customers. These include: consultation does not cover services supported by Thurrock and Southend councils. • Service Support Prioritisation. The questionnaire sets out how the County Council will The questionnaire asks for your views about proposed changes to the supported bus in future prioritise its support for local bus services in Essex, given limited funding. network in your district. This booklet contains the information you need to understand This is based on public responses to two previous consultations and a long standing the changes and allow you to answer the questionnaire. Service entries are listed in assessment of value for money. This will be based on service category and within straight numerical order and cover the entire County of Essex (they are not divided by each category on the basis of cost per passenger journey.