Jazzimprov, November 2008 Interview of Mark Weinstein by Winthop Bedford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Biography-George-ROBERT.Pdf

George ROBERT Born on September 15, 1960 in Chambésy (Geneva), Switzerland, George Robert is internationally reCognized as one of the leading alto saxophonists in jazz today. He started piano at a very early age and at age 10 he began Clarinet lessons at the Geneva Conservatory with LuC Hoffmann. In 1980 he moved to Boston and studied alto saxophone with Joe Viola at the Berklee College of MusiC. In 1984 he earned a Bachelor of Arts in Jazz Composition & Arranging and moved to New York where he enrolled at the Manhattan SChool of MusiC. He studied with Bob Mintzer and earned a Master’s Degree in Jazz PerformanCe in 1987. He played lead alto in the Manhattan SChool of MusiC Big Band for 2 years, whiCh earned in 1985 the 1st Prize in the College Big Band Category in the Down Beat Magazine Jazz Awards In July 1984 he performed on the main stage of the Montreux Jazz Festival and earned an Outstanding PerformanCe Award from Down Beat Magazine. In 1985 & 1986 he toured Europe extensively. In 1987 he met Tom Harrell and together they founded the George Robert-Tom Harrell Quintet (with Dado Moroni, Reggie Johnson & Bill Goodwin). The group Completed 125 ConCerts worldwide between 1987 & 1992, and reCorded 5 albums. He remained in New York City and free-lanCed for 7 years, playing with Billy Hart, Buster Williams, the Lionel Hampton Big Band, the Toshiko Akiyoshi-Lew Tabackin Jazz OrChestra, Joe Lovano, and many others. He met Clark Terry and started touring with him extensively, Completing a 16- week, 65-ConCert world tour in 1991. -

88-Page Mega Version 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010

The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! 88-PAGE MEGA VERSION 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 COMBINED jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! INDEX 2017 Gift Guide •••••• 3 2016 Gift Guide •••••• 9 2015 Gift Guide •••••• 25 2014 Gift Guide •••••• 44 2013 Gift Guide •••••• 54 2012 Gift Guide •••••• 60 2011 Gift Guide •••••• 68 2010 Gift Guide •••••• 83 jazz &blues report jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com 2017 Gift Guide While our annual Gift Guide appears every year at this time, the gift ideas covered are in no way just to be thought of as holiday gifts only. Obviously, these items would be a good gift idea for any occasion year-round, as well as a gift for yourself! We do not include many, if any at all, single CDs in the guide. Most everything contained will be multiple CD sets, DVDs, CD/DVD sets, books and the like. Of course, you can always look though our back issues to see what came out in 2017 (and prior years), but none of us would want to attempt to decide which CDs would be a fitting ad- dition to this guide. As with 2016, the year 2017 was a bit on the lean side as far as reviews go of box sets, books and DVDs - it appears tht the days of mass quantities of boxed sets are over - but we do have some to check out. These are in no particular order in terms of importance or release dates. -

Jazz History, November 2015

JAZZ HISTORY ONLINE NOVEMBER, 2015! Luciana Souza: Passion and Versatility by Thomas Cunniffe Like Ray Charles, Sarah Vaughan, and Bobby McFerrin, Luciana Souza retains her unique identity regardless of the type of music she sings. Her range is staggering. She is a remarkable improviser with recordings that pair her with the most progressive musicians in jazz today. She is also an exquisite interpreter of pop songs, both classic and contemporary, offering definitive renditions of songs as varied as “Never Let Me Go”, “Waters of March” and “The Very Thought of You”. Her three albums of “Brazilian Duos” introduced great songs from Souza’s native land to American audiences by setting her expressive voice against solo guitar accompaniments by Romero Lubambo, Marco Pereira, Toninho Horta, Guilherme Monteiro, Swami, Jr. and her father, Walter Santos. She is also one of the premier interpreters of the music of the contemporary classical composer Osvaldo Golijov, performing his dramatic and vocally challenging music with orchestras and choruses around the world. She has written her own compositions with original words and music, and has also set the poetry of Elizabeth Bishop, Pablo Neruda and Leonard Cohen to her own melodies. JAZZ HISTORY ONLINE NOVEMBER, 2015! However, there is more to Souza’s art than just the mastery of diverse styles. Souza brings deep passion to everything she sings. She picks her repertoire carefully, and is meticulous about finding the right tempo and setting to properly transmit a song’s message. Her recording of “All of Me” sounds like a total act of romantic submission, and her setting of Neruda’s “Tonight I Can Write” conveys a feeling of loneliness and release. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

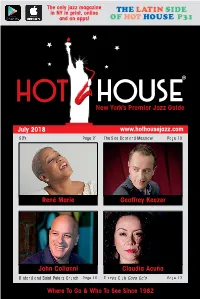

July 2018 92Y Page 21 the Side Door and Mezzrow Page 10

193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 1 DE The only jazz magazine THE LATIN SIDE in NY in print, online P32 and on apps! OF HOT HOUSE P31 July 2018 www.hothousejazz.com 92Y Page 21 The Side Door and Mezzrow Page 10 René Marie Geoffrey Keezer John Colianni Claudia Acuña Birdand and Saint Peter's Church Page 10 Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola Page 17 Where To Go & Who To See Since 1982 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 2 2 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 3 3 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 4 4 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 5 5 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 6 6 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 7 7 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 8 8 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 9 9 193398_HH_July_0 6/25/18 12:30 PM Page 10 WINNING SPINS By George Kanzler WO PIANISTS IN THE PRIME OF time suspending style of the late Shirley their careers bring fresh ideas to their Horn. Tlatest albums, featured in this Winning Gillian delivers her own lyrics on the Spins. Both reach beyond the usual piano pair's collaborative song, "You Stay with trio format—one by collaborating with a Me," and reveals her prowess as a scat vocalist on half the tracks, the other by set- singer on the bubbly "Guanajuato," anoth- ting his piano in the context of a swinging er collaboration with improvised sextet. -

Catching up With: Anne Drummond

Catching Up With: Anne Drummond What has become of Anne Drummond, Then Barron brought Anne onto his In another new project during the the flautist, trombonist, and pianist who more straightahead quintet with vibra- past year, Drummond scored the film impressed mightily during her time at phonist Stefon Harris, drummer Kim Revolving Door. It has no dialogue, and 1999 Garfield High School before head- Thompson, and ace Japanese bassist its “dim but serious message” called for ing off to Manhattan School of Music? Kiyoshi Kitagawa, who has worked with “music with great tension, and dramatic She’s found great success out East. Kenny Garrett, among others. That band contrasts, she says. “We’ll see how it’s While in high school here, Anne won received by audiences once released in several competition and festival awards, the festivals, as I gave it some pretty bold and was one of the pillars of Clarence themes.” Acox’s outstanding program. Recently, Anne has also been touring She is now a regular member of re- with Stefon Harris as he presents his nowned pianist Kenny Barron’s bands, suite, “Portrait of the Promised,” with playing flute. And she has made her mark band members Tim Warfield, Jeremy in other settings, too. Pelt, Mark Gross, Xavier Davis, Terrion But to start at the beginning of her New Gully, and Derick Hodge. They will York career: In 2000, early in her degree record the music, soon. at Manhattan School of Music, the per- Anne also recorded on Harris’s African sonable and unassuming Drummond was Anne Drummond has gone on to great things. -

Facing La Label Success

tk iv t %' /.4 rt' 4 4 1 1 L.A. & ABU Facing La Label Success 11 plume XV No. 45 December 7, 1990 $5.00 Newspaper ,YOU WANTED IT SMOOTHED OUT OX THE TIP "WHEN WILL SEE YOU SMILE AGAIN" THE FIRST BALLAD AND FOURTH HIT SINGLE FROM THE MULTI-PLATINUM ALBUM POISON Produced By Ti m my Gatiing and Alton " Wookie " Ste wart • Executil;le Produced By Lcaoil Silas, Jr. and Miria m nicks .PACA „,1;;4 ONTENTS Publisher SIDINFY Milt ER Assistant Publisher SUSAN MILLER DECEMBER 7. 1990 VOLUME XV. NUMBER 45 Editor-in-Chief RUTH ADKINS ROBINSON Managing Editor JOSEPH ROLAND REYNOLDS VP/Midwest Editor JERO ME SIM MONS Art Department FEATURES LANCE VANTILE WHITFIELD art director COVER STORY—L A & Babyface 24 MARTIN BLACK WELL INTRO —Queen Mother Rage/Adeva 11 typography/computers PROFILE—D-Nice 28 International Dept. DOTUN ADEBAYO. Great Britain STAR TALK—Sybil 38 JONATHAN KING. Japan SECTIONS NORMAN RICH MOND. Canada PUBLISHER'S 5 Columnists NEWS 6 Rap/Roots/Reggae. On Stage LARRIANN FLORES MUSIC REVIEWS 18 What Ever Happened To JAZZ NOTES 16 SPIDER HARRISON Ivory's Notes STEVEN IVORY MUSIC REPORT 22 In Other Media ALAN LEIGH RADIO NEWS 39 Gosp-I TIM SMITH GRAPEVINE/STAR VIEW 46 Record Reviews CHARTS & RESEARCH LARRIANN FLORES 16 TERRY MUGGLETON JAZZ CHART RACHEL WILLIAMS ALBUMS CHART 19 Staff Writers SINGLES CHART 20 CORNELIUS GRANT NEW RELEASE CHART 27 LYNETTE JONES RADIO tiEPORT 31 RACHEL WILLIAMS Production THE NATIONAL ADDS 33 RUSSELL CARTER PROGRAM MER'S POLL 43 ANGELA JOHNSON COLUMNS RAY MYRIE BRITISH INVASION 9 Administration INGRID BAILEY. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

2009 Festival Brochure

ELEVENTH ANNUAL Artisitc Director Jessica Felix James Moody Quartet with special guest Marlena Shaw Randy Weston’s African Rhythms BAy AReA LegendS: Denny Zeitlin - Solo Piano John Handy and the Bay Area Melding Pot Stars of BraziL: Toninho Horta trio with special guest Airto Trio da Paz Leny Andrade with Stephanie ozer esperanza Spalding Quartet Julian Lage group oakland interfaith gospel Choir Richard Howell Quintet Montclair Women’s Big Band Rising Stars Concert with Debbie Poryes trio Jason Bodlovich Quartet Noam Lemish Quintet Jazz tastings – music and wine pairings at tasting rooms around the Plaza and many more performers... Painting (detail): Robin Eschner WWW . HEALDSBURGJAZZFESTIVAL . ORG M A J O R S P O NS or S OFF I C ia L S P O NS or S SA SYST O EM R S A , T I N N C A . S T SRS O S T N A O L I E T Q U U OL IPMENT S BU S I N E SS S P O NS or S HEALDSBURG LODGING GRAPHITE STUDI O COALITION CO MM UNICAT I O N D E S I G N official airline sponsor TA S TI N G R O O M SP O NS OR S GRA N TI N G A G E NC IE S Artiste Winery Steinway Pianos Provided by Bottle Barn/Wine Annex Sherman Clay San Francisco, Topel Winery CA T HE H EALDSBURG J AZZ F ES T IVAL , I NC . IS A 5 0 1 ( C ) ( 3 ) NON - PRO F I T ORGANIZAT ION Friday, May 8: “Havana Nights” Healdsburg Jazz Festival Gala Dinner, Dance, and Auction Celebrating the 11th Anniversary of the Healdsburg Jazz Festival with wine, food, music, and a fund-raising auction to the benefit the Festival’s Education Program. -

Top 5 Chieftains Albums

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • January 8, 2007 Volume 3, Number 7 • $7.95 World Music Q&A: The Chieftains’ PADDY MOLONEY On The Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Diana Krall #1 Smooth Album – Benson/Jarreau #1 College Jazz – Madeleine Peyroux #1 Smooth Single – George Benson #1 World Music – Lynch/Palmieri JazzWeek This Week EDITOR/PUBLISHER Ed Trefzger anuary 10-13 marks the 2007 International Association MUSIC EDITOR Tad Hendrickson fo Jazz Education Annual Conference. Here’s a quick Jplug for the events JazzWeek is sponsoring each day CONTRIBUTING WRITER/ from 10:00 a.m. to noon: PHOTOGRAPHER Tom Mallison Thursday Workshop: Jazz Radio In Crisis: Why That’s A Good Thing PHOTOGRAPHY Barry Solof This session will focus on why some stations are disappearing or seeing big drops in audience, whie other stations with more progressiveapproaches are Contributing Editors seeing audience increases. Panelists will discuss the adoption of more youth- Keith Zimmerman oriented music, the realization that there’s a younger demographic during lat- Kent Zimmerman er hours, and the success stations programming for that audience are seeing. Founding Publisher: Tony Gasparre Panelists: Bob Rogers, Bouille & Rogers consultants; Jenny Toomey, Future of Music Coalition; Gary Vercelli, KXJZ; Linda Yohn, WEMU; Rafi Za- ADVERTISING: Devon Murphy bor. Location: Riverside Ballroom, Sheraon 3rd Fl. Call (866) 453-6401 ext. 3 or email: [email protected] Friday Workshop: Jazz Radio and the Community: How to Make Your Station More Relevant. Stations around the country have made their pro- SUBSCRIPTIONS: gramming more in tune with the local community by reaching out to arts Free to qualified applicants Premium subscription: $149.00 per year, organizations, schools, colleges and universities. -

Susan Pereira & Sabor Brasil

SUSAN PEREIRA & SABOR BRASIL Vocalist, pianist, percussionist, composer and arranger Susan Pereira, a New York native, has been one of the most versatile musicians on that city’s Brazilian music scene since 1983. While deeply rooted in traditional Brazilian styles, her broad background in jazz and world music has enabled her to develop a distinct musical personality. Fluent in Portuguese and French, she is a singer who blends a silky, rich tone with superior vocal technique and is a particularly skilled lyric interpreter and scat singer. Susan’s percussive piano style is enhanced by her mastery of complex Brazilian rhythms and her original Brazilian jazz compositions are a popular part of her performances. Formed in 1991 by Susan and Brazilian drummer Vanderlei Pereira, Sabor Brasil has established itself as one of the most popular Brazilian ensembles in the New York area by fusing traditional Brazilian styles with contemporary jazz. Susan Pereira and Sabor Brasil regularly thrill audiences with their dynamic performances that draw upon influences ranging from hot samba to cool bossa nova, from the elegance of chorinho to the exotic rhythms of Bahia and modern Brazilian jazz. Their début recording Tudo Azul (Riony Records) was released in 2007 and features the core band joined by special guests Claudio Roditi on trumpet, Hendrik Meurkens on harmonica, Romero Lubambo on guitar and Luis Bonilla on trombone. Produced by Susan, the CD includes five of her compositions and one each by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Milton Nascimento, among other selections. Since its inception Sabor Brasil has appeared at many of New York’s leading venues, including Lincoln Center, Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola, Iridium, B.B.