Best Available Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abortion Rates

MEASURE DHS assists countries worldwide in the collection and use of data to monitor and evaluate population, health, and nutrition programs. Funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), MEASURE DHS is implemented by ORC Macro in Calverton, Maryland. The main objectives of the MEASURE DHS project are: 1) to provide decisionmakers in survey countries with information useful for informed policy choices, 2) to expand the international population and health database, 3) to advance survey methodology, and 4) to develop in participating countries the skills and resources necessary to conduct high-quality demographic and health surveys. Information about the MEASURE DHS project or the status of MEASURE DHS surveys is available on the Internet at http://www.measuredhs.com or by contacting: ORC Macro 11785 Beltsville Drive, Suite 300 Calverton, MD 20705 USA Telephone: 301-572-0200 Fax: 301-572-0999 E-mail: [email protected] DHS Analytical Studies No. 8 Recent Trends in Abortion and Contraception in 12 Countries Charles F. Westoff Office of Population Research Princeton University ORC Macro Calverton, Maryland, USA February 2005 This publication was made possible through support provided by the U.S. Agency for Interna- tional Development under the terms of Contract No. HRN-C-00-97-00019-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development Suggested citation: Westoff, Charles F. 2005. Recent Trends in Abortion and Contraception -

Population Advisor Project Ministry of Public Health N

POPULATION ADVISOR PROJECT MINISTRY OF PUBLIC HEALTH N'DJAMENA, CHAD FINAL REPORT Submitted to the Agency for International Development N'Djamena, Chad to the Agency for International Development Washington, D.C. and to REDSO/WCA By Leslie Leila Brandon M.S.W., M.P.H. Population Advisor May 26, 1989 HARVARD INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT FINAL REPORT Submitted to the Agency for International Development N'Djamena, Chad to the Agency for International Development Washington, D.C. and to REDSO/WCA By Leslie Leila Brandon M.S.W., M.P.H. Population Advisor May 26, 1989 HARVARD INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A successful project is never the effort of just one person it takes a cohesive and committed team to make it work. I was very fortunate not only to be a part of several different teams but to have the support of many people who really cared about the success of the first family planning project in Chad. I owe each of them my deepest appreciation and thank them for their generosity and persistent commitment to Chad and to family planning. The follow:ng institutions and individuals are: 1. The Agency for International Development/N'Djamena a) Mrs. Diane Blane: My supervisor at USAID and the one person who should take the credit for making the project work. Without her loyalty, commitment and encouragement the project would have encountered endless obstacles. b) Mr. Bernie Wilder: The USAID representative whose commitment to family planning issues helped make the project successful. c) Mr. John Woods: Deep appreciation for all his support and wisdom in the beginning of the project as the USAID representative. -

Access to Abortion Reports

ACCESS TO ABORTION: An Annotated Bibliography of Reports and Scholarship Second edition (as of April 1, 2020) prepared by The International Reproductive and Sexual Health Law Program Faculty of Law, University of Toronto, Canada, 2020 http://www.law.utoronto.ca/documents/reprohealth/abortionbib.pdf Online Publication History: This edition: Access to Abortion: An Annotated Bibliography of Reports and Scholarship. “Second edition,” current to April 1 2020, published online August 31, 2020 at: http://www.law.utoronto.ca/documents/reprohealth/abortionbib.pdf Original edition: “Access to Abortion Reports: An Annotated Bibliography” (published online January 2008, slightly updated January 2009) has been moved to: http://www.law.utoronto.ca/documents/reprohealth/abortionbib2009.pdf Publisher: The International Reproductive and Sexual Health Law Program Faculty of Law, University of Toronto, 78 Queen’s Park Crescent, Toronto Canada M5S 2A5 Website Reprohealthlaw Blog Contact: reprohealth.law{at}utoronto.ca Acknowledgements: We are most grateful to Professor Joanna Erdman for founding this bibliography in 2008-9. We are also indebted to Katelyn Sheehan (LL.M.) and Sierra Farr (J.D. candidate) for expertly collecting and analyzing new resources up to April 1, 2020, and to Sierra Farr for updating the introduction to this second edition. Updates: Kindly send suggestions for the next edition of this bibliography to: Professor Joanna Erdman, MacBain Chair in Health Law and Policy, Health Law Institute, Schulich School of Law, Dalhousie University, Email: joanna.erdman{at}dal.ca ACCESS TO ABORTION: An Annotated Bibliography of Reports and Scholarship, 2020 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY: Widespread evidence indicates that abortion services remain inaccessible and inequitably available for many people despite legal entitlement.1 This is true in jurisdictions that permit abortion for specific indications (e.g. -

Abortion in Turkey: Women in Rural Areas and the Law

Abortion in Turkey: women in rural areas and the law MATERNAL DEATHS AND country in the Middle East and one of the This paper aims to emphasise that the UNSAFE ABORTIONS 20 most populous countries in the world. law for safe abortion services may itself Worldwide, an estimated 529 000 girls and Women constitute 36.1 million of the represent a barrier to service provision for women die of pregnancy-related causes population, and half of this number is of all women of reproductive age. each year, about one every minute, and reproductive age. Each year approximately many times that number suffer long-term 1.5 million births take place and 728 –1000 REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH injuries and disabilities. Ninety-nine percent mothers die due to pregnancy-, delivery-, PRIORITIES IN TURKEY of all maternal deaths occur in the and birth-related complications. In Turkey, the reproductive health status of developing world. 1–5 Turkey has made progress in improving the population, particularly women, is low Direct causes of pregnancy-related reproductive health since the 1994 compared to other countries at the same deaths worldwide are: International Conference on Population level of development. In spite of improved and Development (ICPD), and the life expectancy, maternal and infant • severe bleeding, 25%; government has reflected the ICPD targets mortality rates are still above the regional • infection, 15%; and strategies in the country’s averages, as compared with Europe. Some • unsafe abortion, 13%; Development Plan. Furthermore, a National findings of the 2003 Turkish Demographic • hypertensive disorders, 12%; Strategic Plan for Women’s Health and Health Survey (TDHS) may be significant in • obstructed labour, 8%; and Family Planning was developed, which explaining the low status of reproductive • other, 8%. -

Abortion Morbidity in Uganda: Evidence from Two Communities

Men in Abortion Decision-Making and Care in Uganda Ann M. Moore 1, Gabriel Jagwe-Wadda 2, and Akinrinola Bankole 3 1Corresponding author: Senior Research Associate, Guttmacher Institute, NY, NY, USA 2 Deceased, last position was as Lecturer, Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda 3 Director of International Research, Guttmacher Institute, NY, NY, USA 1 Summary Abortion is illegal in Uganda except to save the life of the woman. Nevertheless, the practice is quite common: About 300,000 induced abortions occur annually among Ugandan women aged 15–49 (Singh et al., 2005) and a large proportion of these women require treatment for postabortion complications. In a male dominant culture as exists in Uganda where men control most of the financial resources, men play a critical part in determining whether women receive a safe abortion or appropriate treatment if they experience abortion complications. This study examines men’s role in determining women’s access to a safer 1 abortion and postabortion care. It draws on in-depth interviews (IDIs) carried out in 2003 with 61 women aged 18–60 and 21 men aged 20–50 from Kampala and Mbarara, Uganda. Respondents’ descriptions of men’s involvement in women’s abortion care agreed: Men’s attitudes about abortion often prevented women from involving them in either the abortion or postabortion care. Most men believe that if a woman is having an abortion, it must be because she is pregnant with another man’s child. If the woman does experience postabortion complications, many men said that they cannot support a woman in such a situation seeking care because if it had been his child, she would not have had a clandestine abortion. -

The Foreign Service Journal, February 1993

PROBLEMS AND PRECEDENTS SOMALIA AS VICTIM: EACT AND FICTION Tv tuai/UiiLiiiru SEEKING A SOLUTION VIGNETTE PROM OLD MOGADISHU Li\I • V UlLliliUVt VI I I • I -I • 1 Li.I I LKLllTI I I I I I M l-LUS: IxLHUUl- LILTULI lill liRtlltiyilci tlLLLL Liu.' LLULULALLIUVCIL UliLLLLLLcUllUS When it’s time to entrust your valuable belongings for moving or storage, you can select Interstate with confidence. Since 1943 Interstate has represented a Now that your choice is made, call Interstate and tradition of excellence and quality for all your ask for our State Department Coordinators at (703) moving needs. For the sixth consecutive year, 569-2121, extension 233, or if you are out of town, Interstate has been selected as a primary (800) 336-4533, extension 233. contractor to provide moving and storage services for United States Department of State Our competition is good, but let us show personnel. Do you want a moving company you that Interstate is the best!! with trained professional movers, climate- It’s your choice! controlled storage, personal consultation throughout your move, a proven record of performance? Then choose Interstate. We invite you to ask your colleagues, review our ™INTERSTATE commendation letters from prior moves, and EXCELLENCE IN MOVING A STORAGE visit our facilities. 5801 Rolling Road, Springfield, VA 22152-1041 MC 1745 FMC 2924 When You Go Abroad, We Go Abroad. ★ ★ Clements & Company The Leaders in Insurance for the Foreign Service. At Clements & Company, Our Primary Products Include: we are the leaders in providing • Automobile domestic and international • Household Effects coverage for the foreign • Personal Liability service community. -

Comprehensive Abortion Care Pilot Project in Tigray, Ethiopia FINAL REPORT

May 2011 Comprehensive Abortion Care Pilot Project in Tigray, Ethiopia FINAL REPORT Tigray Regional Health Bureau (TRHB) is the semi-autonomous public health administrative body for the region of Tigray, Ethiopia. The Bureau is responsible for developing region-specific policy, implementing federal and regional public health programs, and overseeing all health service delivery. Venture Strategies Innovations (VSI) is a California-based nonprofit organization committed to improving women’s health in developing countries by creating access to effective and affordable technologies on a large scale. VSI’s innovative approach involves partnerships that build upon existing infrastructure, resources and markets. VSI focuses on reducing barriers to access and enhancing human capacity to bring about sustainable improvements in health. Bixby Center for Population, Health, and Sustainability is a research center located at the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) School of Public Health. The Center is dedicated to developing innovations to improve reproductive health in resource-poor settings, including reliable health information systems, local access to essential technologies, and guidelines for prioritizing interventions to maximize health impact. The Center assists in the implementation of maternal health programs and seeks to improve the health outcomes of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable women and their families. Tigray Regional Health Bureau P.O. Box 7 Mekele, Tigray, Ethiopia Tel +251 34 440 02 22 / +251 34 440 93 66 Website: -

APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS

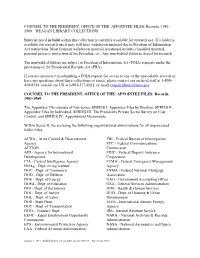

COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS Material noted in bold within this collection is currently available for research use. If a folder is available for research use it may still have withdrawn material due to Freedom of Information Act restrictions. Most frequent withdrawn material is national security classified material, personal privacy, protection of the President, etc. Any non-bolded folder is closed for research. The non-bolded folders are subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests under the provisions of the Presidential Records Act (PRA). If you are interested in submitting a FOIA request for access to any of the unavailable records or have any questions about these collections or series, please contact our archival staff at 1-800- 410-8354, outside the US at 1-805-577-4012, or email [email protected] COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981-1989 The Appointee File consists of four series: SERIES I: Appointee Files by Position; SERIES II: Appointee Files by Individual; SERIES III: The President's Private Sector Survey on Cost Control, and SERIES IV: Appointment Memoranda Within Series II, we are using the following organizational abbreviations for all unprocessed folder titles: ACDA - Arms Control & Disarmament FBI - Federal Bureau of Investigation Agency FCC - Federal Communications ACTION Commission AID - Agency for International FDIC - Federal Deposit Insurance Development Corporation CIA - Central Intelligence Agency FEMA - Federal Emergency Management DOAg - Dept. of Agriculture Agency DOC - Dept. of Commerce FNMA - Federal National Mortgage DOD - Dept. of Defense Association DOE - Dept. -

A Discourse Analysis of the Abortion Debate in Turkey and the United States

T.C. KADİR HAS UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF AMERICAN CULTURE AND LITERATURE A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE ABORTION DEBATE IN TURKEY AND THE UNITED STATES M.A. THESIS IN AMERICAN STUDIES BY SULTAN KOMUT İSTANBUL, 2009 T.C. KADİR HAS UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF AMERICAN CULTURE AND LITERATURE A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE ABORTION DEBATE IN TURKEY AND THE UNITED STATES M.A. THESIS IN AMERICAN STUDIES BY SULTAN KOMUT ADVISOR ASSIST.PROF. MARY LOU O’NEIL İSTANBUL, 2009 iv ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to observe and analyze abortion issue in the contexts of Turkey and America via various written and spoken discourses such as; religion, ethic, economy, social norms and women's rights and thus comparing these two countries. Throughout the representation of Turkish society's view on abortion, the predominant religion of the country; Islam and its regulations have been the main focus as they are the inevitable parts of forming the traditions, beliefs and behaviors of the society and thus affecting people's discourses on the cores of abortion issue which are mainly sexuality, virginity, honor killing and social codes. In the second part of the study, American people's views on the abortion debate have been examined through the opposing discourses of pro-life and pro-choice supporters who make abortion a hot issue throughout the country, which influences even the politics. This study does not mean to be a discourse analysis but an overview of the abortion debate in Turkey and America by means of various discourses prevalent in both countries. -

“It Was As If Society Didn't Want a Woman to Get an Abortion”: a Qualitative Study in Istanbul, Turkey☆ ⁎ Katrina A

Contraception 95 (2017) 154–160 Original research article “It was as if society didn't want a woman to get an abortion”: a qualitative study in Istanbul, Turkey☆ ⁎ Katrina A. MacFarlanea, Mary Lou O'Neilb, Deniz Tekdemirc, Angel M. Fostera,d, aFaculty of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada bGender and Women's Studies Research Center, Kadir Has University, Istanbul, Turkey cIndependent Consultant, Istanbul, Turkey dInstitute of Population Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada Received 19 May 2016; revised 22 July 2016; accepted 25 July 2016 Abstract Introduction: In 1983, abortion without restriction as to reason was legalized in Turkey. However, at an international conference in 2012, the Prime Minister condemned abortion and announced his intent to draft restrictive abortion legislation. As a result of public outcry and protests, the law was not enacted, but media reports suggest that barriers to abortion access have since worsened. Objectives: We aimed to conduct a qualitative study exploring women's recent abortion experiences in Istanbul, Turkey. Study design: In 2015, we conducted 14 semi-structured in-depth interviews with women aged 18 or older who had obtained abortion care in Istanbul on/after January 1, 2009. We employed a multimodal recruitment strategy and analyzed these interviews for content and themes using deductive and inductive techniques. Results: Women reported on a total of 19 abortions. Although abortion care is available in private facilities, only one public hospital provides abortion services without restriction as to reason. Women who had multiple abortions in different facility types described quality of care more positively in the private sector. -

Table of Contents

GABON COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS L. Michael Rives 1961-1963 Director for Central African Countries- State Department, Washington, DC Dorothy E. Eardley 1963-1965 Secretary to the Ambassador, Libreville Robert V. Keeley 1963-1965 Congo-Leopoldville Desk Officer- Central African Affairs, Washington, DC Thompson R. Buchanan 1966-1967 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville John Propst Blane 1966-1969 Desk Officer, State Department, Washington, DC Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1967-1969 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville Richard Funkhouser 1969-1970 Ambassador, Gabon Edward Gibson Lanpher 1969-1971 Political Officer, Libreville Nancy Forbord 1969-1972 Representative to African-American Institute, Libreville Fernando E. Rondon 1970 Madagascar Desk Officer- State Department, Washington, DC Laurent E. Morin 1970 Alternate Country Director- African Bureau, Washington, DC James K. Bishop Jr. 1970-1972 Desk Officer- Central African Affairs, Washington, DC John R. Countryman 1971-1975 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville John A. McKesson, III 1971-1975 Ambassador, Gabon Michael P.E. Hoyt 1972-1974 Rhodesian Desk Officer-State Department, Washington, DC 1 Andrew Steigman 1975-1977 Ambassador, Gabon Arthur T. Tienken 1978-1981 Ambassador, Gabon Francis Terry McNamara 1981-1984 Ambassador, Gabon Herman J. Rossi III 1982-1984 Deputy Chief of Mission, Libreville Larry C. Williamson 1984-1987 Ambassador, Gabon Ronald K. McMullen 1988-1990 Economic-Commercial Officer, Libreville Keith L. Wauchope 1989-1992 Ambassador, Gabon Joseph C. Wilson, IV 1992-1995 Ambassador, Gabon L. MICHAEL RIVES Director for Central African Countries- State Department Washington, DC (1961-1963) L. Michael Rives was born in New York in 1921. He received a bachelor's degree from Princeton University in 1947 and joined the Foreign Service in 1950. -

Erosion of Reproductive Rights in Turkey Ayse Dayi

a. dayi / abortion in the middle east and north africa, 57-68 Neoliberal Health Restructuring, Neoconservatism and the Limits of Law: Erosion of Reproductive Rights in Turkey ayse dayi Abstract Through focusing on the neoliberal “Health Transformation Programme” launched in 2003 in Turkey, I show how reproductive law can be modified by neoliberal mechanisms that are implemented with neoconservative policies and pressures. The paper builds on original data collected in 2014 and 2015 through focus groups and interviews with health practitioners in family health centers and women receiving reproductive care in Izmir, Diyarbakir, Van, and Gaziantep. The data analysis informed by writings on the debt economy by Maurizio Lazzarato and Bifo Berardi and transnational feminist theory demonstrate that neoliberal mechanisms of “dismantling the public” interact with pronatalist policies and pressures to erode women’s reproductive rights in Turkey. This has resulted in (1) indebtedness of women through out-of-pocket payments for contraception and abortion, (2) indebtedness of providers through performance measures, (3) reduction in the quality of reproductive care, and (4) reduction in access to reproductive care itself (contraception, counseling, and abortion). There is a need to pay attention to neoliberal mechanisms and the legal framings of reproductive rights to fully understand the limitations of law and counter the neoliberal and conservative assaults on women’s sexual and reproductive rights. Ayse Dayi, PhD, is an Academy in Exile Fellow at the Margherita Von Brentano Center, Freie University, Berlin, Germany. Please address correspondence to the author. Email: [email protected]. Competing interests: None declared. Copyright © 2019 Dayi. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.