Willem Sandberg – Portrait of an Artist – Chapter 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vienna Method in Amsterdam: Peter Alma's Office for Pictorial Statistics Benjamin Benus, Wim Jansen

The Vienna Method in Amsterdam: Peter Alma’s Office for Pictorial Statistics Benjamin Benus, Wim Jansen The Dutch artist and designer, Peter Alma (see Figure 1), is today remembered for his 1939 Amstel Station murals, as well as for Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/desi/article-pdf/32/2/19/1715594/desi_a_00379.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 his earlier involvement with the Cologne-based Gruppe progres- siver Künstler [Progressive Artists’ Group]. Yet Alma also pro- duced an extensive body of information graphics over the course of the 1930s. Working first in Vienna at the Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum [Social and Economic Museum] (GWM) and later setting up an independent design firm in Amsterdam, Alma became one of the principal Dutch practitioners and promoters of the design approach known as the “Vienna Method of Picto- rial Statistics.” To date, most accounts of this method’s history have focused on its chief inventor, Austrian social scientist Otto Figure 1 Neurath, and his principal collaborators, Germans Marie Neurath August Sander, photograph of Peter Alma, (née Reidemeister) and Gerd Arntz.1 Yet Alma’s work in pictorial late 1920s. Private collection. Reproduced by permission from Sinja L. Alma and statistics also constitutes a substantial chapter in this history, Peter L. Alma. although it has not yet been fully appreciated or adequately docu- mented.2 In addition to providing an account of Alma’s role in the 1 For a detailed history of the Vienna development and dissemination of the Vienna Method, this essay Method, see Christopher Burke, Eric assesses the nature of Alma’s contribution to the field of informa- Kindel, and Sue Walker, eds., Isotype: tion design and considers the place of his pictorial statistics work Design and Contexts, 1925–1971 within his larger oeuvre. -

This Cannot Happen Here Studies of the Niod Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

This Cannot Happen Here studies of the niod institute for war, holocaust and genocide studies This niod series covers peer reviewed studies on war, holocaust and genocide in twentieth century societies, covering a broad range of historical approaches including social, economic, political, diplomatic, intellectual and cultural, and focusing on war, mass violence, anti- Semitism, fascism, colonialism, racism, transitional regimes and the legacy and memory of war and crises. board of editors: Madelon de Keizer Conny Kristel Peter Romijn i Ralf Futselaar — Lard, Lice and Longevity. The standard of living in occupied Denmark and the Netherlands 1940-1945 isbn 978 90 5260 253 0 2 Martijn Eickhoff (translated by Peter Mason) — In the Name of Science? P.J.W. Debye and his career in Nazi Germany isbn 978 90 5260 327 8 3 Johan den Hertog & Samuël Kruizinga (eds.) — Caught in the Middle. Neutrals, neutrality, and the First World War isbn 978 90 5260 370 4 4 Jolande Withuis, Annet Mooij (eds.) — The Politics of War Trauma. The aftermath of World War ii in eleven European countries isbn 978 90 5260 371 1 5 Peter Romijn, Giles Scott-Smith, Joes Segal (eds.) — Divided Dreamworlds? The Cultural Cold War in East and West isbn 978 90 8964 436 7 6 Ben Braber — This Cannot Happen Here. Integration and Jewish Resistance in the Netherlands, 1940-1945 isbn 978 90 8964 483 8 This Cannot Happen Here Integration and Jewish Resistance in the Netherlands, 1940-1945 Ben Braber Amsterdam University Press 2013 This book is published in print and online through the online oapen library (www.oapen.org) oapen (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative initiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. -

Sheila Hicks CV

SHEILA HICKS Born Hastings, Nebraska 1934 EDUCATION 1959 MFA, Yale University, New Haven, CT 1957 BFA, Yale University, New Haven, CT SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Sheila Hicks: Life Lines, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France, February 6 – April 30, 2018. Sheila Hicks: Send Dessus Dessous, Domaine de Chaumont-sur Loire Centre d’Arts et de Nature, Chaumont-sur Loire, France, March 30, 2018 – February 2, 2019. Down Side Up, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY, May 24 – July 6, 2018. 2017 Sheila Hicks: Glossolalia, Domaine de Chaumont-sur Loire Centre d’Arts et de Nature, Chaumont-sur Loire, France, April 1 – November 5, 2017. Sheila Hicks: Hilos Libres. El Textil y Sus Raíces Preshispánicas, 1954-2017, Museo Amparo, Puebla, Mexico, November 4, 2017 – April 2, 2018. Sheila Hicks: Stones of Piece, Alison Jaques Gallery, London, England, October 4 – November 11, 2017. Sheila Hicks: Hop, Skip, Jump, and Fly: Escape from Gravity, High Line, New York, New York, June 2017 – March 2018. Sheila Hicks: Au-delà, Museé d’Arte Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France, December 1 – May 20, 2018. 2016 Si j’étais de laine, m’accepteriez-vous?, galerie frank elbaz, Paris, France, September 10 – October 15, 2016. Apprentissages, Festival d’Automne, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, France, September 13 – October 2, 2016; Nanterre-Amandiers, Paris, France, December 9 – 17, 2016. Sheila Hicks: Material Voices, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, June 5 – September 4, 2016; travels to: Textile Museum of Canada, Toronto, Canada, October 6, 2016 – February 5, 2017. Sheila Hicks: Why Not?, Textiel Museum, Tilburg, The Netherlands, March 5 – June 5, 2016. -

Finding Aid to the Grabhorn Letterpress Printing Ephemera Collection

Finding Aid to the Grabhorn Letterpress Printing Ephemera Collection Finding Aid by: Samantha Cairo-Toby Finding Aid date: November 2018 Book Arts & Special Collections San Francisco Public Library 100 Larkin Street San Francisco 94102 (415)557-4560 [email protected] Summary Information: Repository: Book Arts & Special Collections Creator: Grabhorn, Robert Title: Finding Aid for the Grabhorn Letterpress Printing Ephemera Colletion Finding Aid Filing Title: Grabhorn Letterpress Printing Ephemera Collection ID: BASC 1 Date [inclusive]: 950 CE-2018 (bulk 1890-2018) Physical Description: 230.4 linear feet (300 boxes) Physical Location: Collection is stored on site. Language of Material: Collection materials are primarily in English, but includes French, German, Dutch, Italian, Latin, Welsh, Russian, Greek, Spanish, and Chinese. Abstract: The collection contains ephemeral materials printed with metal or wood type using a letterpress. Ephemeral materials include: prospectuses, notices, fliers, postcards, broadsides, bookmarks, chapbooks, pamphlets and small books/accordion fold books. The collection dates range from 950 CE (China) to present, with the bulk of the collection ranging from 1890 CE to present. Additions to the Collection are ongoing. The earliest printed materials in the collection come from China and Europe, but the bulk of the collection is from California and the United States of America printed in the 20th century. Preferred Citation: [Identification of item/Title of folder], Grabhorn Letterpress Printing Ephemera Collection (BASC 1), Book Arts & Special Collections, San Francisco Public Library. Custodial History: Ephemera has been part of Book Arts & Special Collections since 1925 when William Randolph Young, a library trustee, was instrumental in establishing the Max Kuhl Collection of rare books and manuscripts, after the destruction of the Library’s collection in the 1906 earthquake and fire. -

Hicks, Sheila CV

SHEILA HICKS Born Hastings, Nebraska 1934 EDUCATION 1959 MFA, Yale University, New Haven, CT 1957 BFA, Yale University, New Haven, CT SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Sheila Hicks: Off the Grid, The Hepworth Wakefield, Wakefield, United Kingdom, November 27, 2021 – May 2022 Sheila Hicks: Music to My Eyes, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK, June 4 – July 31, 2021 Sheila Hicks: Cosmic Vibrations, Galerie Nähst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder, Vienna, Austria, May 28 – August 21, 2021 Sheila Hicks: Cosmic Arrivals, Francesca Minini, Milan, Italy, May 19 - July 17, 2021 Sheila Hicks: The Questioning Column, Moody Center for the Arts at Rice University, Houston, TX, May 17 – August 28, 2021 2020 Sheila Hicks, Galerie nächst St. Stephan, Vienna, Austria, December 22, 2020 – February 6, 2021 Sheila Hicks: Thread, Trees, River, Museum of Applied Arts [MAK] Vienna, Vienna, Austria, December 10, 2020 – April 18, 2021 2019 Reencuentro, Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, Santiago, Chile, August 8, 2019 – January 31, 2020, curated by Carolina Arévalo Sheila Hicks: Secret Structures, Looming Presence, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX, June 30, 2019 – January 12, 2020 Sheila Hicks: Seize, Weave Space, Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas, TX, May 11 – August 18, 2019 Sheila Hicks: Line by Line, Step by Step, Demisch Danant, New York, NY, April 29 – June 8, 2019 Sheila Hicks: Campo Abierto (Open Field), The Bass, Miami Beach, FL, April 13 – September 29, 2019 2018 MIGDALOR, Magasin III Jaffa, Tel Aviv, Israel, October 11, 2018 – February 15, 2019 Down Side Up, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY, May 24 – July 6, 2018 Sheila Hicks: Sens Dessus Dessous, Domaine de Chaumont-sur Loire Centre d’Arts et de Nature, Chaumont-sur Loire, France, March 30, 2018 – February 2, 2019 Sheila Hicks: Life Lines, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France, February 6 – April 30, 2018, curated by Michel Gauthier 2017 Sheila Hicks: Au-delà, Museé d’Arte Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France, December 1, 2017 – May 20, 2018 Sheila Hicks: Hilos Libres. -

Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility Full Text Edited by Paula Marincola

QUESTIONS OF PRACTICE Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility Full Text Edited by Paula Marincola THE PEW CENTER FOR ARTS & HERITAGE / PCAH.US / @PEWCENTER_ARTS CURATING NOW: IMAGINATIVE PRACTICE/PUBLIC RESPONSIBILITY OCT 14-15 2000 Paula Marincola Robert Storr Symposium Co-organizers Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative Funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts Administered by The University of the Arts The Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative is a granting program funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and administered by The University of the Arts, Philadelphia, that supports exhibitions and accompanying publications.“Curating Now: Imaginative Practice/Public Responsibility” has been supported in part by the Pew Fellowships in the Arts’Artists and Scholars Program. Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative 230 South Broad Street, Suite 1003 Philadelphia, PA 19102 215-985-1254 [email protected] www.philexin.org ©2001 Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative All rights reserved ISBN 0-9708346-0-8 Library of Congress catalog card no. 2001 131118 Book design: Gallini Hemmann, Inc., Philadelphia Copy editing: Gerald Zeigerman Printing: CRW Graphics Photography: Michael O’Reilly Symposium and publication coordination: Alex Baker CONTENTS v Preface Marian Godfrey vii Introduction and Acknowledgments Paula Marincola SATURDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2000 AM 3 How We Do What We Do. And How We Don’t Robert Storr 23 Panel Statements and Discussion Paul Schimmel, Mari-Carmen Ramirez, Hans-Ulrich Obrist,Thelma Golden 47 Audience Question and Answer SATURDAY, -

Women Memory Agency and Some Things Hidden

SOME THINGS HIDDENTHINGS SOME HIDDEN THINGS THINGS SOME SOME AND AND AGENCY AGENCY MEMORY MEMORY RESISTANCE 2018 / 2017 WOMEN Highlights of The Female Perspective Perspective Female The of Highlights 2017/2018 programme Hélène Amouzou Alexis Blake SOME THINGS Sara Blokland Lynn Hershman Leeson HIDDEN Zhana Ivanova Bertien van Manen Charlott Markus Shana Moulton Femmy Otten CASTRUM PEREGRINI Marijn Ottenhof 18-26 Nov 2017 Cauleen Smith Batia Suter FRAMER FRAMED curated by Charlott Markus HIGHLIGHTS OF THE FEMALE PERSPECTIVE PROGRAMME PROGRAMME PERSPECTIVE FEMALE THE OF HIGHLIGHTS 18 Jan-11 March 2018 and Nina Folkersma PERSPECTIVE THE FEMALE Contents 05 Preface Michaël Defuster WOMEN AND AGENCY 06 For today I am a woman 48 Free speech. Nina Folkersma Intersectionality in theory and practice WOMEN AND RESISTANCE Adeola Enigbokan 10 ‘Das passt zu Dir’ 52 Guess who’s coming to Annet Mooij dinner too? Patricia Kaersenhout 15 Jacoba van Tongeren Or: How women disappeared from the history 56 The modest resistance of of resistance Marjan Schwegman Wendelien van Oldenborgh Lieneke Hulshof 19 Letter to ‘her’ Pieter Paul Pothoven 59 Thinking diferently and imagining things diferently An exchange with Katerina Gregos 23 Red, white and blue laundry Nat Muller Bianca Stigter 26 Artist contribution: 64 Colophon Ronit Porat WOMEN AND MEMORY 30 The warp and weft SOME THINGS HIDDEN of memory Renée Turner 02 Note to the reader Charlott Markus and Nina Folkersma 34 Some notes on women, labour and textile craft 04 The politics of the invisible Christel Vesters -

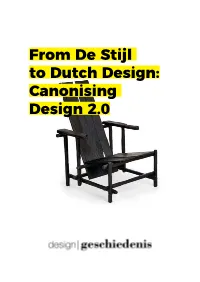

From De Stijl to Dutch Design: Canonising Design 2.0 Table of Contents

From De Stijl to Dutch Design: Canonising Design 2.0 Table of Contents From De Stijl to Dutch Design: Canonising Design 2.0 3 A Note from the Chair of the Dutch Design History Society 7 Frederike Huygen Introduction: The Canonisation of Dutch design 8 Joana Meroz The Dance around the Red Blue Chair 15 Ida van Zijl Bauhaus Houses and the Design Canon: 1923 - 2019 25 Jeremy Aynsley The Exploded Design Canon: Open Source Design Criticism 34 in the 21st Century Alice Twemlow The I Love SU T-shirt 43 Cyril Tjahja and Marlom Aguiar Design from an International Perspective 57 Renilde Steeghs Emergent Nature-Cultures 61 Thought Collider Studio Minale-Maeda and Governmental Subsidies 63 Studio Minale-Maeda Migrationlab 65 Laura Pana 2 From De Stijl to Dutch Design: Canonising Design 2.0 In 2017, tourism agencies, governments, museums, and design academies in the Netherlands are celebrating the centennial of 100 years of De Stijl and 25 years of Dutch Design. On December 9, 2016, the annual Dutch Design History Society symposium was dedicated to critically reflect on the production of such a centen- nial and design canonisation in general. While De Stijl’s implied beginnings (1917) are relatively uncontroversial, the proposition that Dutch design originates from 1992 is much more so. This par- ticular construction of ‘Dutch design’ as an avant-garde phenomenon that started in the 1990s with Droog design, and is today centred around the Design Academy Eindhoven, is a clear example of design canonisation at work. In this process, what comes to count as (good) design and the knowledge that surrounds it is produced, selectively, in line with specific (cultural, political, economic, etc.) agendas. -

Sammlerleidenschaft – Leidenschaftlich Sammler •Sammler – Leidenschaft – Museum

•Impulse •THEMA: Sammlerleidenschaft – leidenschaftlich Sammler •Sammler – Leidenschaft – Museum. Universal- April sammler und Volksbildner Georg Wieninger aus Schärding •Georg Gasser – Initiator des Naturmuseum Südtirol 2010 •Musikinstrumente für Adel und Bürgerschaft. Die Sammlung von Franz Ferk im Pokrajinski Museum Ptuj (Slowenien) •Die Hanns Schell Collection in Graz. Museum für Schloss, Schlüssel, Kästchen und Eisenkunstguss •Spuren bewahren 09/4 – Kultur erleben – Zeichen setzen. Walter Just und die Gründung des lebensspuren.museum •Die Anfänge der Samm- lung Leopold •Der Fürst als Sammler. Neuerwerbungen unter Hans-Adam II. von und zu Liechtenstein •SCHAUPLÄTZE: 10/1 Da, dort & dazwischen – 20 Jahre Kulturkontakt Austria •Die Öffentlichkeit im Museumsdepot •www.monteprojects.at •KIKIS KOSMOS – Die Kunst der KIKI KOGELNIK •OBJEKTiv FOKUSsiert: Vermeers Malkunst THEMA Sammler- leidenschaft Herausgegeben vom Museumsbund Österreich ISSN 1015-6720 € 14,30 GOLDENER HORIZONT 4000 Jahre Nomaden der Ukraine SCHLOSSMUSEUM LINZ 21. März 2010 – 22. August 2010 Schlossmuseum Linz Öffnungszeiten: Schlossberg 1 (Tummelplatz 10) Di, Mi, Fr: 9.00 – 18.00 Uhr A 4010 Linz Do: 9.00 – 21.00 Uhr T: +43 732 774419 Sa, So, Fei: 10.00 – 17.00 Uhr [email protected] Mo geschlossen www.schlossmuseum.at Editorial Geschätzte Leserinnen und Leser! ammeln ist nicht nur eine und Unvollständigkeit der Sammlung, an Sletztlich die zentrale Aufgabe ei- den fehlenden Mitteln, am fehlenden nes Museums, sondern auch eine Lei- Platz – vielleicht auch ein wenig an der denschaft. Erfolgreich sammeln funk- fehlenden gesellschaftlichen Akzep- tioniert nur mit einem hohen Einsatz tanz des Sammelns, vor allem der Mu- an Wissen und Begeisterung. Das gilt seen. Denn in gegenwärtigen, media- für eine erfolgreiche Sammeltätigkeit len, gesellschaftlichen und politischen im musealen Kontext genauso wie bei Diskussionen hat dieses Aufgabenfeld einem Privatsammler. -

Willem Van Konijnenburg Rijnders, M.L.J

VU Research Portal Willem van Konijnenburg Rijnders, M.L.J. 2007 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Rijnders, M. L. J. (2007). Willem van Konijnenburg: Leonardo van de Lage Landen. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Willem van Konijnenburg Leonardo van de Lage Landen VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Willem van Konijnenburg Leonardo van de Lage Landen ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. L.M. Bouter, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de faculteit der Letteren op donderdag 13 december 2007 om 10.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Maria Lambertha Johanna Rijnders geboren te Geldrop 1 promotor: prof.dr. -

Leven En Werk Van Stedenbouwkundig Architecte Lotte Stam-Beese

'Want de grond behoort ons allen toe' : leven en werk van stedenbouwkundig architecte Lotte Stam-Beese Citation for published version (APA): Oosterhof, J. (2018). 'Want de grond behoort ons allen toe' : leven en werk van stedenbouwkundig architecte Lotte Stam-Beese. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Document status and date: Gepubliceerd: 06/11/2018 Document Version: Uitgevers PDF, ook bekend als Version of Record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Paris | London

Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London Holland Herold Siegal, Nina: A New Hope February 2017 Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (left page) Den Haag Gemeentemuseum maxhetzler.com Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London Cobra Art A New Hope After WWII, a group of artists set out to change the world forever. With their Cobra movement, they aimed to create a utopia through spontaneous poetry and painting. Text Nina Siegal Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (left page) Den Haag Gemeentemuseum maxhetzler.com Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London Cobra Art ovember 1948: an international group of artists gathered at the Café de l’Hotel Notre-Dame on the Quai Saint-Michel in Paris. Why? To start nothing less than an artistic revolution. NTheir goal was to leave the past – WWII and its destruction – behind, and everything they had been taught that art should be. They “The artists wanted to forge ahead with a new kind of art that was primal, emotive, bold, and above shared the all, experimental. Their movement, called Cobra, after the idea that cities from which they came – Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam – was a fierce, wild, art should untamed and joyous one. Its goal was to help create a utopian society of the future built on be as free playfulness, spontaneity, collaboration and ‘free thought’. as possible” The movement burned like a furious fire for only three years, from 1948 to 1951, and then died out almost as quickly, which is Page 26: why many people have not heard of it. But Child IV (1951) by Karel Appel. today, many art historians regard Cobra as c/o Pictoright Amsterdam.