Chinese Smallholder Farmers' Engagements in Ghanaian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Strategic Plan for Immunization 2014–2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Regional Strategic Plan for Immunization 2014 - 2020 AFRO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Regional Strategic Plan for Immunization 2014-2020 1. Vaccination – trends 2. Immunization Programs – organization and administration 3. Child Mortality – prevention and control 4. Communicable Diseases – prevention and control 5. Healthcare Disparities 6. Regional Health Planning 7. Strategic planning I. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Africa ISBN: 978 929 023 2780 (NLM Classification: WA 115) © WHO Regional Office for Africa, 2015 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. All rights reserved. Copies of this publication may be obtained from the Library, WHO Regional Office for Africa, P.O. Box 6, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo (Tel: +47 241 39100; Fax: +47 241 39507; E-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate this publication, whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution, should be sent to the same address. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Localizing the Decent Work Agenda Through South-South and City-To-City Cooperation

Localizing the Decent Work Agenda through South-South and City-to-City Cooperation Department of Partnerships and Field Support International Labour Office Localizing the Decent Work Agenda through South-South and City-to-City Cooperation Department of Partnerships and Field Support International Labour Office Copyright © International Labour Organization 2015 First published 2015 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organisations may make copies in accordance with licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Localizing the Decent Work Agenda through South-South and City-to-City Cooperation, Geneva 2015 ISBN: 978-92-2-130321-3 (print) ISBN: 978-92-2-130322-0 (web pdf) ISBN: 978-92-2-030356-6 (CD-ROM) ILO Cataloguing in Publication Data The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rest solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. -

Independent Evaluation of the ILO's Strategy to Address HIV and AIDS and the World of Work /Carla Henry, Mei Zegers; International Labour Office, Evaluation Unit

Independent evaluation of the ILO’s strategy to address HIV and AIDS and the world of work For more information: International Labour Offi ce (ILO) Tel.: (+ 41 22) 799 6440 Evaluation Unit (EVAL) Fax: (+41 22) 799 6219 OCTOBER 2011 4, route des Morillons E-mail: [email protected] CH-1211 Geneva 22 http://www.ilo.org/evaluation Switzerland EVALUATION UNIT Independent evaluation of the ILO’s strategy to address HIV and AIDS and the world of work International Labour Office September 2011 Copyright © International Labour Organization 2011 First published 2011 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Henry, Carla; Zegers, Mei Independent evaluation of the ILO's strategy to address HIV and AIDS and the world of work /Carla Henry, Mei Zegers; International Labour Office, Evaluation Unit. - Geneva: ILO, 2011 1 v. ISBN print: 978-92-2-125422-5 -

And Trade Development Roadmap of the Gambia 2018-2022

Strategic Youth and Trade Development Roadmap of The Gambia 2018-2022 Republic of The Gambia STRATEGIC YOUTH AND TRADE DEVELOPMENT ROADMAP OF THE GAMBIA 2018-2022 Republic of The Gambia This Strategic Youth and Trade Development Roadmap (SYTDR ) was developed on the basis of the process, methodology and technical assistance of International Trade Centre (ITC ) within the framework of its Trade Development Strategy programme. ITC is the joint agency of the World Trade Organization and the United Nations. As part of ITC’s mandate of fostering sustain- able development through increased trade opportunities, the Chief Economist and Export Strategy section offers a suite of trade-related strategy solutions to maximize the development pay-offs from trade. ITC-facilitated trade development strategies and roadmaps are oriented to the trade objectives of a country or region and can be tailored to high-level economic goals, specific development targets or particular sectors, allowing policymakers to choose their preferred level of engagement. The views expressed herein do not reflect the official opinion of ITC. Mention of firms, products and product brands does not imply the endorsement of ITC. This document has not been formally edited by ITC. © International Trade Centre 2018 ITC encourages reprints and translations for wider dissemination. Short extracts may be freely reproduced, with due acknowledge- ment, using the suggestion citation. For more extensive reprints or translations, please contact ITC, using the online permission request form -

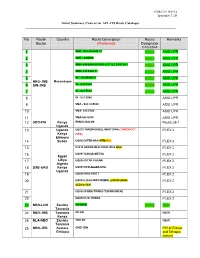

Initial Summary Content for AFI ATS Route Catalogue

APIRG/19 WP/14 Appendix 3.2D Initial Summary Content for AFI ATS Route Cataloque ____________________________________________________________________________________________ No Route Country Route Description Route Remarks . Sector (Preferred) Designator ICAO-ESAF 1 VBR - S15 40 E042 37 UT512 ASIO UPR 2 VBR – GADNO UT513 ASIO UPR VBR- S18 E041 13 VBR-S18 15.2 E041 04.1 ASIO UPR 3 UT515 4 VBR- S19 E040 37 UT516 ASIO UPR 5 VL - S19 E040 37 UT517 ASIO UPR HKG-JNB Mozambique 6 SIN-JNB VL- S20 E040 UT518 ASIO UPR 7 VL- S21 E040 UT519 ASIO UPR 8 IN - S21 E040 ASIO UPR 9 VMA - S23 30 E040 ASIO UPR 10 VMA- S25 E040 ASIO UPR 11 VMA-S26 E040 ASIO UPR 12 ADD-FIH Kenya EKBUL-NALOS RouteLab 1 Uganda 13 Uganda UQ579 TAREM-EKBUL-IMKIT-DWA (TAREM-DCT- iFLEX 2 Kenya DWA) Ethiopia 14 Sudan UQ583 KITEK-KNA-KTM-KSL iFLEX 2 15 UT419 ASKON-MLK-TIKAT-OHA QHA iFLEX 2 UQ597 DANAD-METSA iFLEX 2 16 Egypt 17 Libya UQ598 DITAR-PASAM iFLEX 2 Algeria 18 DXB-GRU Kenya UQ599 KFR-ALSEP-KHG iFLEX 2 Uganda 19 UQ595 KHG-KIRET iFLEX 2 20 UQ594 LIGAT-OWT-ORMOL-LOPID-UMINI- iFLEX 2 SEDVA-YEN 21 UQ596 IPOBA-TWARG-TUKAM-IMRAD iFLEX 2 22 UQ853 DJA-TWARG iFLEX 2 23 NBO-LUN Zambia KS-SINGI UT428 NEW Tanzania 24 NBO-JNB Tanzania NV-DO NEW Kenya 25 NLA-NBO Zambia VND-NV NEW Tanzania 26 NBO-JED Asmara GWZ-JDW FIR of Eritrea Ethiopia and Ethiopia closure APIRG/19 WP/14 Appendix 3.2D Initial Summary Content for AFI ATS Route Cataloque ____________________________________________________________________________________________ 27 ABV-SSG Nigeria BIMAT-ARDEX NEW No Route Country Route Description Remarks . -

LABOUR MARKET PROFILE SIERRA LEONE - 2020 Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Analytical Unit

LABOUR MARKET PROFILE SIERRA LEONE - 2020 Danish Trade Union Development Agency, Analytical Unit The profile provides a comprehensive overview of the labour market’s structures, development, and challenges. Danish Trade Union Development Agency Sierra Leone Labour Market Profile 2020 PREFACE The Danish Trade Union Development Agency (DTDA) is the reforms, status vis-à-vis ILO conventions and labour development organisation of the Danish trade union standards, among others. movement. It was established in 1987 by the two largest Danish confederations – Danish Federation of Trade Unions Main sources of data and information for LMPs are: (Danish acronym: LO) and Danish Confederation of • As part of program implementation and monitoring, Professionals (Danish acronym: FTF). These two national partner organisations provide annual organisations merged to become the Danish Trade Union narrative progress reports, including information on Confederation (Danish acronym: FH) in January 2019. The labour market developments. Furthermore, specific name of this organisation, former known as the LO/FTF types of data and information relating to key Council, was changed to DTDA. indicators are collected using a unique data collection tool. The work of DTDA is in line with the sustainable development goals and the International Labour • National statistical institutions and international Organization’s (ILO) Decent Work Agenda (DWA). The databanks are used as a source for collection of four Decent Work Pillars: Creating decent jobs, general (statistical) data and information. It includes guaranteeing rights at work, extending social protection the ILOSTAT and NATLEX, World Bank Open Data, and promoting social dialogue forms the overall ITUC Survey of Violations of Trade Union Rights, the development objective of DTDA’s interventions in the South. -

13 April 2020 Excellency, Further to General Assembly Resolution 73/292, Entitled, “2020 United Nations Conference to Support

THE PRESIDENT OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY 13 April 2020 Excellency, Further to General Assembly resolution 73/292, entitled, “2020 United Nations Conference to Support the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”, in particular paragraph 16 of Annex II, viz: • “The President of the General Assembly shall also draw up lists of representatives of other relevant non-governmental organizations, civil society organizations, academic institutions, the scientific community, the private sector and philanthropic organizations whose work is relevant to the Conference, who may participate in the Conference and the preparatory meeting as observers, taking into account the principles of transparency and of equitable geographical representation, and shall submit the proposed lists to Member States for their consideration on a non-objection basis. The President of the General Assembly shall bring a list to the attention of the General Assembly before the preparatory meeting and, in any case, no later than December 2019, and, where applicable, shall bring another list to the attention of the Assembly before the Conference and, in any case, no later than April 2020.” Reference is also made to my letter dated 13 April 2020, informing that draft decision A/74/L.48, entitled “2020 United Nations Conference to Support the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14: Conserve and Sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development, -

Methodology Used to Prepare Pest Alert Lists

EU project number 613678 Strategies to develop effective, innovative and practical approaches to protect major European fruit crops from pests and pathogens Work package 1. Pathways of introduction of fruit pests and pathogens Deliverable 1.3. PART 3 - Methods for the preparation of alert lists of pests for individual fruit species Partners involved: EPPO (Grousset F, Petter F, Suffert M) and JKI (Steffen K, Wilstermann A, Schrader G). DROPSA is funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration (grant agreement no. 613678). www.dropsaproject.eu [email protected] DROPSA Methods for the preparation of alert lists of pests for individual fruit species A review of recent literature (Steffen et al. 20151 and the associated Excel file Fruit_pest_list_review_final_xls2) showed that pests and pathogens have already been introduced into Europe with fruit trade. The next task of this Work Package was to produce an “alert list” of pests and pathogens likely to be introduced into Europe with the import of several fruit species from outside Europe. A priority list of fruits was established (see Part 2 Analysis of fruit production and imports in the EU to select species for pathway studies – thereafter Selection of fruit3) and the project was able to prepare Alert Lists for the first four: apple; Vaccinium; grapes; oranges and mandarins. Current legislation was checked to analyse how it covers the identified pathways. The methods followed for the preparation of alert lists of pests for individual fruit species are presented. They were originally based on those of the EPPO Tomato study (EPPO, 2015), and adjusted to take account of the aims of Task 1.3, and of the experience gained during the EPPO Tomato Study and during Dropsa, from one fruit to the next. -

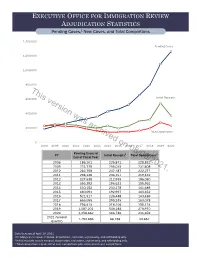

EOIR Workload and Adjudication Statistics

EXECUTIVE OFFICE FOR IMMIGRATION REVIEW ADJUDICATION STATISTICS Pending Cases,1 New Cases, and Total Completions 1,400,000 Pending Cases 1,200,000 1,000,000 800,000 This Initial Receipts 600,000 version 400,000 was 200,000 archived Total Completions 0 on 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 201608/05/2021. 2017 2018 2019 2020 Pending Cases at FY Initial Receipts2 Total Completions3 End of Fiscal Year 2008 186,101 225,871 228,831 2009 223,779 255,035 231,608 2010 262,758 247,187 222,277 2011 298,228 238,157 219,132 2012 327,638 212,935 186,080 2013 356,292 196,623 155,961 2014 430,152 230,178 141,689 2015 460,093 192,997 143,652 2016 521,517 228,448 143,489 2017 656,095 295,245 163,078 2018 796,513 316,106 195,123 2019 1,087,201 546,248 276,970 2020 1,258,882 368,746 231,659 2021 (Second 1,293,896 66,158 43,652 Quarter) Data Generated: April 19, 2021 1 Pending cases equals removal, deportation, exclusion, asylum-only, and withholding only. 2 Initial receipts equals removal, deportation, exclusions, asylum-only, and withholding only. 3 Total completions equals initial case completions plus subsequent case completions. EXECUTIVE OFFICE FOR IMMIGRATION REVIEW ADJUDICATION STATISTICS New Cases and Total Completions 600,000 Initial Receipts 500,000 400,000 300,000This 200,000 version Total Completions 100,000 was archived 0 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 on Average Average Fiscal Year Initial Receipts1 Initial Receipts Total Completions08/05/2021.2 Total Completions per Month per Month 2008 225,871 18,823 -

Groundwater Monitoring in the SADC Region

Groundwater Monitoring in the SADC Region Overview prepared for the Stockholm World Water Week 2013 Groundwater Monitoring in the SADC Region This report is a summary on groundwater monitoring practices in the SADC region. A brief overview is made for each country to capture the current state of national monitoring networks in the SADC region and their future challenges. It is a compilation of the information shared during 2nd regional workshop of the Global Groundwater Monitoring Network. We thank the workshop participants for their active participation and their valuable input. This report would not have been possible without their collaboration and timely contributions. 2 Groundwater Monitoring in the SADC Region Content 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.1. The Global Groundwater Monitoring Network ............................................................................................ 5 2. Current monitoring and assessment practices in the SADC region ....................................................................... 6 2.1. Southern African Development Community ................................................................................................ 6 2.2. Angola ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.3. Botswana ................................................................................................................................................... -

Impact of Ebola Outbreak on Reproductive Health Services in a Rural District of Sierra Leone: a Prospective Observational Study

Open access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029093 on 4 September 2019. Downloaded from Impact of Ebola outbreak on reproductive health services in a rural district of Sierra Leone: a prospective observational study Gianluca Quaglio,1,2,3 Francesca Tognon,4 Livio Finos,5 David Bome,6 Santigie Sesay,6 Atiba Kebbie,7 Francesco Di Gennaro,8 Bienvenu Salim Camara,9 Claudia Marotta, 10 Vincenzo Pisani,7 Zainab Bangura,7 Damiano Pizzol,3 Annalisa Saracino,8 Walter Mazzucco, 10 Susan Jones,11 Giovanni Putoto3 To cite: Quaglio G, Tognon F, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Finos L, et al. Impact of Ebola Objectives To assess the trends concerning utilisation of outbreak on reproductive health maternal and child health (MCH) services before, during ► The study uses data from a remote rural district in services in a rural district of and after the Ebola outbreak, quantifying the contribution Sierra Leone: a prospective Sierra Leone, with a 6-year observational period. of a reorganised referral system (RS). observational study. BMJ Open Data have been collected in a prospective way, re- Design A prospective observational study of MCH 2019;9:e029093. doi:10.1136/ ducing the potential bias in the accuracy of the data services. bmjopen-2019-029093 reported by other studies carried out in countries Setting Pujehun district in Sierra Leone, 77 community affected by Ebola. ► Prepublication history and health facilities and 1 hospital from 2012 to 2017. ► Data from pre, intra and post-Ebola periods allowed additional material for this paper Main outcome measures MCH utililization was evaluated are available online. -

Assessing the Rights to Water and Sanitation: Between Institutionalization and Radicalization

ARTICLE ASSESSING THE RIGHTS TO WATER AND SANITATION: BETWEEN INSTITUTIONALIZATION AND RADICALIZATION MARGARET L. SATTERTHWAITE* ABSTRACT In the past two decades, the human rights to water and sanitation have emerged, matured, and taken their place at the center of discussions about rights, sustainable development, global health, and climate change. While there was early hope that these rightsÐespecially the right to waterÐwould provide a strong basis for rejecting the commodi®cation of essential services spurred by neoliberalism, as they were institutionalized, the rights to water and sanitation have in many places been tamed, if not neutralized. However, while the human rights framework concerning water and sanitation has accommodated powerful economic imperatives, it still holds promise as a vehicle for governments, courts, andÐperhaps most importantlyÐmovements facing the harsh realities of radi- cal inequality, vulnerability to disaster, and advancing climate change. This Article provides an overview of the conceptual and theoretical issues behind the rights to water and sanitation, an account of the normative development of the rights in law, and an appraisal of the key debates concerning water and sanita- tion as human rights today. I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 316 A. The Reality: Water and Sanitation Around the World . 317 B. Map of the Article............................... 319 II. RIGHTS EMERGING: WATER AND SANITATION UNDER HUMAN RIGHTS LAW ...................................... 320 A. History of the Right to Water and Sanitation . 320 B. The Rights to Water and Sanitation Crystalize at the United Nations ..................................... 324 * Professor of Clinical Law and Faculty Director, Center for Human Rights and Global Justice and Bernstein Institute for Human Rights, NYU School of Law.