Type Your Uppercase Title Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Strategic Plan for Immunization 2014–2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Regional Strategic Plan for Immunization 2014 - 2020 AFRO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Regional Strategic Plan for Immunization 2014-2020 1. Vaccination – trends 2. Immunization Programs – organization and administration 3. Child Mortality – prevention and control 4. Communicable Diseases – prevention and control 5. Healthcare Disparities 6. Regional Health Planning 7. Strategic planning I. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Africa ISBN: 978 929 023 2780 (NLM Classification: WA 115) © WHO Regional Office for Africa, 2015 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. All rights reserved. Copies of this publication may be obtained from the Library, WHO Regional Office for Africa, P.O. Box 6, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo (Tel: +47 241 39100; Fax: +47 241 39507; E-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate this publication, whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution, should be sent to the same address. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Report of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission

REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION The Government should immediately carry out counselling services, especially to those who lost their entire families to avoid mental breakdown. It is not too late to counsel the victims because they have not undergone any counselling at all. The community also seeks an apology from the Government, the reason being that the Government was supposed to protect its citizens yet it allowed its security forces to violently attack them and, therefore, perpetrated gross violation of their rights. Anybody who has been My recommendation to this Government is that it should involved in the killing address the question of equality in this country. We do of Kenyans, no matter not want to feel as if we do not belong to this country. We what position he holds, demand to be treated the same just like any other Kenyan in should not be given any any part of this country. We demand for equal treatment. responsibility. Volume IV KENYA REPORT OF THE TRUTH, JUSTICE AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION Volume IV © Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission, 2013 This publication is available as a pdf on the website of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (and upon its dissolution, on the website of its successor in law). It may be copied and distributed, in its entirety, as long as it is attributed to the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission and used for noncommercial educational or public policy purposes. Photographs may not be used separately from the publication. Published by Truth Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC), Kenya ISBN: 978-9966-1730-3-4 Design & Layout by Noel Creative Media Limited, Nairobi, Kenya His Excellency President of the Republic of Kenya Nairobi 3 May 2013 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL By Gazette Notice No. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface…………………………………………………………………….. i 1. District Context………………………………………………………… 1 1.1. Demographic characteristics………………………………….. 1 1.2. Socio-economic Profile………………………………………….. 1 2. Constituency Profile………………………………………………….. 1 2.1. Demographic characteristics………………………………….. 1 2.2. Socio-economic Profile………………………………………….. 1 2.3. Electioneering and Political Information……………………. 2 2.4. 1992 Election Results…………………………………………… 2 2.5. 1994 By-Election results……………………………………….. 2 2.6. 1996 By-Election results……………………………………….. 3 2.7. 1997 Election Results…………………………………………… 3 2.8. Main problems……………………………………………………. 3 3. Constitution Making/Review Process…………………………… 4 3.1. Constituency Constitutional Forums (CCFs)………………. 4 3.2. District Coordinators……………………………………………. 6 4. Civic Education………………………………………………………… 7 4.1. Phases covered in Civic Education 4.2. Issues and Areas Covered 7 7 5. Constituency Public Hearings……………………………………… 8 5.1. Logistical Details…………………………………………………. 5.2. Attendants Details……………………………………………….. 8 5.3. Concerns and Recommendations…………………………….. 8 9 Appendices 23 1. DISTRICT PROFILE Starehe constituency falls within Nairobi province. 1.1. Demographic Characteristics Male Female Total District Population by Sex 1,153,828 989,426 2,143,254 Total District Population Aged 18 years & 397,038 429,639 826,677 Below Total District Population Aged Above 18 756,790 559,787 1,316,577 years District Population by sex 1,153,828 989,426 2,143,254 Population Density (persons/Km2) 3,079 1.2. Socio-economic Profile Nairobi province has: • The highest urban population in Kenya. • The highest population density. • A young population structure. • The highest monthly mean household income in the country and the least number of malnourished children • More than 50% of the population living in absolute poverty • High inequalities by class and other social economic variables • Very low primary and secondary school enrollments • Poor access to safe drinking water and sanitation Nairobi has eight constituencies. -

Toand Television Irrom June 25

TOAND TELEVISION IRROM JUNE 25 1tVeledrillt 44 111vot-ir Percy MILTON BERLE GRACIE ALLEN ')N McNEILL RALPH EDWARDS BIG SISTER LANNY ROSS filter Winchell Contest Winners - i (o+1) Vie, fodLut, tiA9ti otcuut SKIN -SAFE SOLITAIRI The only founda- tion- and -pawder make -up with clinicol evidence- certified by leading skin specialists from coast to coast -that it DOES NOT CLOG PORES, cause skin texture change or inflammation of hair follicle ar other gland opening. Na other liquid, powder, creom or cake "founda- tion" moke -up offers such positive proof of safety for your skin. biopsy- specimen flown by Cell Chapman. Jewels by Seaman-Schepps. See the loveliest you that you've ever seen -the minute you use Solitair cake make -up. Gives your skin a petal- smooth appearance -so flatteringly natural that you look as if you'd been born with it! Solitair is entirely different- a special feather -weight formula. Clings longer. Outlasts powder. Hides little skin faults -yet never feels mask -like, never looks "made -up." Like finest face creams, Solitair contains Lanolin to protect against dryness. Truly -you'll be lovelier with this make -up that millions prefer. No better quality. Only $1.00. Cake Make -Up * Fashion -Point Lipstick Seven new fashion -right shades Yes -the first and only lipstick with point actually shaped to curve of your lips. Applies color quicker, easier, more evenly. New, exciting "Dreamy Pink" shade - and six new reds. So creamy smooth- contains Lanolin -stays on so long. Exquisite case. $1.00 *Slanting cap with red enameled circle identifies the famous 'Fashion -Point and shows you exact (¡orí*iwnn tameGm color of lipstick inside. -

Alan Sillitoe the LONELINESS of the LONG- DISTANCE RUNNER

Alan Sillitoe THE LONELINESS OF THE LONG- DISTANCE RUNNER Published in 1960 The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner Uncle Ernest Mr. Raynor the School-teacher The Fishing-boat Picture Noah's Ark On Saturday Afternoon The Match The Disgrace of Jim Scarfedale The Decline and Fall of Frankie Buller The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner AS soon as I got to Borstal they made me a long-distance cross-country runner. I suppose they thought I was just the build for it because I was long and skinny for my age (and still am) and in any case I didn't mind it much, to tell you the truth, because running had always been made much of in our family, especially running away from the police. I've always been a good runner, quick and with a big stride as well, the only trouble being that no matter how fast I run, and I did a very fair lick even though I do say so myself, it didn't stop me getting caught by the cops after that bakery job. You might think it a bit rare, having long-distance crosscountry runners in Borstal, thinking that the first thing a long-distance cross-country runner would do when they set him loose at them fields and woods would be to run as far away from the place as he could get on a bellyful of Borstal slumgullion--but you're wrong, and I'll tell you why. The first thing is that them bastards over us aren't as daft as they most of the time look, and for another thing I'm not so daft as I would look if I tried to make a break for it on my longdistance running, because to abscond and then get caught is nothing but a mug's game, and I'm not falling for it. -

Localizing the Decent Work Agenda Through South-South and City-To-City Cooperation

Localizing the Decent Work Agenda through South-South and City-to-City Cooperation Department of Partnerships and Field Support International Labour Office Localizing the Decent Work Agenda through South-South and City-to-City Cooperation Department of Partnerships and Field Support International Labour Office Copyright © International Labour Organization 2015 First published 2015 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organisations may make copies in accordance with licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Localizing the Decent Work Agenda through South-South and City-to-City Cooperation, Geneva 2015 ISBN: 978-92-2-130321-3 (print) ISBN: 978-92-2-130322-0 (web pdf) ISBN: 978-92-2-030356-6 (CD-ROM) ILO Cataloguing in Publication Data The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rest solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. -

Independent Evaluation of the ILO's Strategy to Address HIV and AIDS and the World of Work /Carla Henry, Mei Zegers; International Labour Office, Evaluation Unit

Independent evaluation of the ILO’s strategy to address HIV and AIDS and the world of work For more information: International Labour Offi ce (ILO) Tel.: (+ 41 22) 799 6440 Evaluation Unit (EVAL) Fax: (+41 22) 799 6219 OCTOBER 2011 4, route des Morillons E-mail: [email protected] CH-1211 Geneva 22 http://www.ilo.org/evaluation Switzerland EVALUATION UNIT Independent evaluation of the ILO’s strategy to address HIV and AIDS and the world of work International Labour Office September 2011 Copyright © International Labour Organization 2011 First published 2011 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Henry, Carla; Zegers, Mei Independent evaluation of the ILO's strategy to address HIV and AIDS and the world of work /Carla Henry, Mei Zegers; International Labour Office, Evaluation Unit. - Geneva: ILO, 2011 1 v. ISBN print: 978-92-2-125422-5 -

And Trade Development Roadmap of the Gambia 2018-2022

Strategic Youth and Trade Development Roadmap of The Gambia 2018-2022 Republic of The Gambia STRATEGIC YOUTH AND TRADE DEVELOPMENT ROADMAP OF THE GAMBIA 2018-2022 Republic of The Gambia This Strategic Youth and Trade Development Roadmap (SYTDR ) was developed on the basis of the process, methodology and technical assistance of International Trade Centre (ITC ) within the framework of its Trade Development Strategy programme. ITC is the joint agency of the World Trade Organization and the United Nations. As part of ITC’s mandate of fostering sustain- able development through increased trade opportunities, the Chief Economist and Export Strategy section offers a suite of trade-related strategy solutions to maximize the development pay-offs from trade. ITC-facilitated trade development strategies and roadmaps are oriented to the trade objectives of a country or region and can be tailored to high-level economic goals, specific development targets or particular sectors, allowing policymakers to choose their preferred level of engagement. The views expressed herein do not reflect the official opinion of ITC. Mention of firms, products and product brands does not imply the endorsement of ITC. This document has not been formally edited by ITC. © International Trade Centre 2018 ITC encourages reprints and translations for wider dissemination. Short extracts may be freely reproduced, with due acknowledge- ment, using the suggestion citation. For more extensive reprints or translations, please contact ITC, using the online permission request form -

QUESTION TRACKER, 2020 the Question Tracker Provides an Overview of the Current Status of Questions Before the National Assembly During the Year 2020

REPUBLIC OF KENYA THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY TWELFTH PARLIAMENT (FOURTH SESSION) QUESTION TRACKER, 2020 The Question Tracker provides an overview of the current status of Questions before the National Assembly during the year 2020. N0. QUESTION Date Nature of Date Date Remarks (Constituency/County, Member, Ministry, Question and Committee) Received Question Asked and Replied and No. in Dispatched Before the Order to Committee Paper Directorate of Committee 1 The Member for Baringo Central (Hon. Joshua Kandie, MP) to ask the 06/01/2020 Ordinary 18/02/2020 05/03/2020 Concluded Cabinet for Transport, Infrastructure, Housing & Urban Development: - (001/2020) tabled on 13/03/2020 (i) Could the Cabinet Secretary explain the cause of delay in construction of the Changamwe Roundabout along Kibarani - Mombasa Road in Mombasa County whose completion has been pending for over three years? (ii) What measures have been put in place by the Ministry to ensure that the said project is completed considering its importance to the tourism sector? (To be replied before the Departmental Committee on Transport, Public Works and Housing) 2 The Member for Lamu County (Hon. Ruweida Obo, MP) to ask the Cabinet 29/01/2020 Ordinary 18/02/2020 05/03/2020 Concluded Secretary for Lands: - (002/2020) Following a land survey carried out by the Ministry in January 2019 and later reviewed on 20th August 2019 in Vumbe area of Lamu East Constituency, Lamu County, could the Cabinet Secretary provide the report of the subdivision exercise and the number of plots arrived at? Status as at Friday, October 16, 2020 Directorate of Legislative and Procedural Services, Table Office Department The National Assembly (To be replied before the Departmental Committee on Lands) 3 The Nominated Member (Hon. -

Making the Loyalist Bargain: Surrender, Amnesty and Impunity in Kenya's Decolonization, 1952–63

Original citation: Anderson, David M.. (2017) Making the Loyalist bargain : surrender, amnesty and impunity in Kenya's decolonization, 1952–63. The International History Review, 39 (1). pp. 48-70. Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/86182 Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work of researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. This article is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0) and may be reused according to the conditions of the license. For more details see: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ A note on versions: The version presented in WRAP is the published version, or, version of record, and may be cited as it appears here. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications The International History Review ISSN: 0707-5332 (Print) 1949-6540 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rinh20 Making the Loyalist Bargain: Surrender, Amnesty and Impunity in Kenya's Decolonization, 1952–63 David M. Anderson To cite this article: David M. Anderson (2017) Making the Loyalist Bargain: Surrender, Amnesty and Impunity in Kenya's Decolonization, 1952–63, The International History Review, 39:1, 48-70, DOI: 10.1080/07075332.2016.1230769 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2016.1230769 © 2016 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 19 Sep 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 452 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rinh20 Download by: [137.205.202.97] Date: 27 February 2017, At: 03:26 THE INTERNATIONAL HISTORY REVIEW, 2017 VOL. -

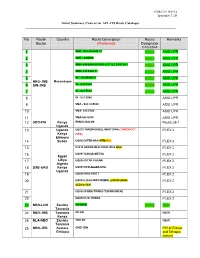

Initial Summary Content for AFI ATS Route Catalogue

APIRG/19 WP/14 Appendix 3.2D Initial Summary Content for AFI ATS Route Cataloque ____________________________________________________________________________________________ No Route Country Route Description Route Remarks . Sector (Preferred) Designator ICAO-ESAF 1 VBR - S15 40 E042 37 UT512 ASIO UPR 2 VBR – GADNO UT513 ASIO UPR VBR- S18 E041 13 VBR-S18 15.2 E041 04.1 ASIO UPR 3 UT515 4 VBR- S19 E040 37 UT516 ASIO UPR 5 VL - S19 E040 37 UT517 ASIO UPR HKG-JNB Mozambique 6 SIN-JNB VL- S20 E040 UT518 ASIO UPR 7 VL- S21 E040 UT519 ASIO UPR 8 IN - S21 E040 ASIO UPR 9 VMA - S23 30 E040 ASIO UPR 10 VMA- S25 E040 ASIO UPR 11 VMA-S26 E040 ASIO UPR 12 ADD-FIH Kenya EKBUL-NALOS RouteLab 1 Uganda 13 Uganda UQ579 TAREM-EKBUL-IMKIT-DWA (TAREM-DCT- iFLEX 2 Kenya DWA) Ethiopia 14 Sudan UQ583 KITEK-KNA-KTM-KSL iFLEX 2 15 UT419 ASKON-MLK-TIKAT-OHA QHA iFLEX 2 UQ597 DANAD-METSA iFLEX 2 16 Egypt 17 Libya UQ598 DITAR-PASAM iFLEX 2 Algeria 18 DXB-GRU Kenya UQ599 KFR-ALSEP-KHG iFLEX 2 Uganda 19 UQ595 KHG-KIRET iFLEX 2 20 UQ594 LIGAT-OWT-ORMOL-LOPID-UMINI- iFLEX 2 SEDVA-YEN 21 UQ596 IPOBA-TWARG-TUKAM-IMRAD iFLEX 2 22 UQ853 DJA-TWARG iFLEX 2 23 NBO-LUN Zambia KS-SINGI UT428 NEW Tanzania 24 NBO-JNB Tanzania NV-DO NEW Kenya 25 NLA-NBO Zambia VND-NV NEW Tanzania 26 NBO-JED Asmara GWZ-JDW FIR of Eritrea Ethiopia and Ethiopia closure APIRG/19 WP/14 Appendix 3.2D Initial Summary Content for AFI ATS Route Cataloque ____________________________________________________________________________________________ 27 ABV-SSG Nigeria BIMAT-ARDEX NEW No Route Country Route Description Remarks . -

Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya This Page Intentionally Left Blank Pal-Alam-00Fm.Qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page Iii

pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page i Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya This page intentionally left blank pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page iii Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya S. M. Shamsul Alam, PhD pal-alam-00fm.qxd 6/14/07 6:00 PM Page iv Rethinking Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya Copyright © S. M. Shamsul Alam, PhD, 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quo- tations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS. Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN-13: 978-1-4039-8374-9 ISBN-10: 1-4039-8374-7 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Alam, S. M. Shamsul, 1956– Rethinking Mau Mau in colonial Kenya / S. M. Shamsul Alam. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-4039-8374-7 (alk. paper) 1. Kenya—History—Mau Mau Emergency, 1952–1960. 2. Mau Mau History. I. Title. DT433.577A43 2007 967.62’03—dc22 2006103210 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library.