Assessing the Rights to Water and Sanitation: Between Institutionalization and Radicalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jean Ziegler's Campaign Against America

JEAN ZIEGLER’S CAMPAIGN AGAINST AMERICA A Study of the Anti-American Bias of the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food Table of Contents Key Findings...................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 3 Our Study .......................................................................................................................... 3 Conclusions........................................................................................................................ 4 Recommendations............................................................................................................. 7 Table: A Comparison of Jean Ziegler’s Treatment of the United States and Food Emergency Countries.............................................................................................. 8 Selected Quotes from Jean Ziegler.................................................................................. 9 Bibliography of Jean Ziegler’s Statements................................................................... 11 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................... 13 About UN Watch............................................................................................................. 13 United Nations Watch 1, rue de Varembe Case postale 191 1211 Geneva 20, Switzerland -

Regional Strategic Plan for Immunization 2014–2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Regional Strategic Plan for Immunization 2014 - 2020 AFRO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Regional Strategic Plan for Immunization 2014-2020 1. Vaccination – trends 2. Immunization Programs – organization and administration 3. Child Mortality – prevention and control 4. Communicable Diseases – prevention and control 5. Healthcare Disparities 6. Regional Health Planning 7. Strategic planning I. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Africa ISBN: 978 929 023 2780 (NLM Classification: WA 115) © WHO Regional Office for Africa, 2015 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. All rights reserved. Copies of this publication may be obtained from the Library, WHO Regional Office for Africa, P.O. Box 6, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo (Tel: +47 241 39100; Fax: +47 241 39507; E-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate this publication, whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution, should be sent to the same address. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Les Rebelles Zaïrois Entrent Dans Kinshasa Elections Une filiale B Les Troupes De M

LeMonde Job: WMQ1805--0001-0 WAS LMQ1805-1 Op.: XX Rev.: 17-05-97 T.: 11:12 S.: 111,06-Cmp.:17,11, Base : LMQPAG 45Fap:99 No:0352 Lcp: 196 CMYK b TELEVISION a RADIO H MULTIMEDIA CINÉMA LA PENTAPHONIE Les Sénégalais TÉLÉVISION-RADIO « Requiem pour A la poursuite un massacre », du « Singe soleil », voyagent ou l’enfer un reportage sonore sur le Net. Page 35 de la guerre, extraordinaire. par le cinéaste soviétique Page 26 MULTIMÉDIA Elem Klimov. Page 22 CNN, les métamorphoses du village a global ENQUÊTE Ted Turner veut Loin de renoncer à ses ambitions planétaires, le fleuron du groupe Turner, renforcé par le mariage avec Time Warner, continue sur la voie du développement, tout en s’adaptant aux évolutions de la mondialisation. CNN s’oriente vers une certaine régionalisation internationale, avec une version en espagnol, et essaie changer le monde de tenir compte des particularismes locaux. Le charismatique Ted Turner conserve cependant son esprit missionnaire, à l’échelle du globe : il espère toujours changer le monde. Pages 2 et 3 CNN Histoire(s) de Wonder Jeux vidéo : a Après « Reprise », le film les grands classiques Les meilleurs d’Hervé Le Roux, Richard Copans propose une version Les meilleurs titres de CD-ROM courte pour la télévision. d’aventures, de stratégie ou d’action. Mêmes interviews, autre Ils peuvent pour la plupart être achetés montage. Mêmes bouffées à prix cassé et constituer un bon fonds de vie, autre regard. Page 5 de CD-ludothèque. Pages 32 et 33 titres de CD-ROM SEMAINE DU 19 AU 25 MAI 1997 CINQUANTE-TROISIÈME ANNÉE – No 16269 – 7 F DIMANCHE 18 - LUNDI 19 MAI 1997 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Affaire Elf : Les rebelles zaïrois entrent dans Kinshasa Elections une filiale b Les troupes de M. -

List of Water Remunicipalisations in Asia and Worldwide - As of April 2014

Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU) www.psiru.org List of water remunicipalisations in Asia and worldwide - As of April 2014 by Emanuele Lobina, David Hall and Vladimir Popov [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] A briefing commissioned by Public Services International (PSI) www.world-psi.org This PSIRU Briefing has been commissioned by the Public Services International (PSI) for presentation at the Civil Society Panel Discussion 3 - Social Gains through Inclusive Growth: PPPs (Public-Private Partnerships) or PUPs (Public-Public Partnerships)? A Call for "Remunicipalization" – held at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Board of Governors of the Asian Development Bank, Astana, Kazakhstan, 4 May 2014 (http://www.adb.org/annual-meeting/2014/csp). This PSIRU Briefing draws on the following PSIRU Reports, among other sources. Lobina, E., Hall, D. (2013) Water Privatisation and Remunicipalisation: International Lessons for Jakarta. PSIRU Reports, prepared for submission to Central Jakarta District Court Case No. 527/Pdt.G/2012/PN.Jkt.Pst, November 2013 (http://www.psiru.org/sites/default/files/2014-W-03- JAKARTANOVEMBER2013FINAL.docx). Hall, D. (2012) Re-municipalising municipal services in Europe. PSIRU Report commissioned by the European Federation of Public Service Unions (EPSU), May 2012, revised November 2012 (http://www.psiru.org/sites/default/files/2012-11-Remun.docx). PSIRU, Business School, University of Greenwich, Park Row, London SE10 9LS, U.K. Website: www.psiru.org Email: [email protected] -

Jean Ziegler

Jean Ziegler Das Leben eines Rebellen Bearbeitet von Jürg Wegelin 1. Auflage 2011. Buch. 192 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 312 00485 0 Format (B x L): 13,3 x 21 cm Gewicht: 310 g schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Jürg Wegelin Jean Ziegler Das Leben eines Rebellen ISBN: 978-3-312-00485-0 Weitere Informationen oder Bestellungen unter http://www.hanser-literaturverlage.de/978-3-312-00485-0 sowie im Buchhandel. © Nagel und Kimche im Carl Hanser Verlag, München Inhalt Vorwort 7 Dichtung und Wahrheit 17 Jugend in Thun Die Suche nach einem neuen Weltbild 35 Vom Couleurstudenten zum Vorläufer der Achtundsechziger Lehr- und Wanderjahre 49 Zwei Schlüsselerlebnisse Das erste Interventionsbuch 63 Als Nestbeschmutzer am Pranger Genosse Professor 73 Zieglers Wirken an der Universität Der weiße Neger 91 Zieglers Faszination für Afrika Im finanziellen Würgegriff 105 Ziegler in den Mühlen der Justiz Beim «Roten Kreuz des Kapitalismus» 121 Zieglers Arbeit in der Politik In der Zwangsjacke der Diplomatie 143 Ziegler auf der Uno-Bühne Im Zentrum eine rote Patchworkfamilie 163 Zieglers privates Beziehungsnetz Mit Ehrungen überschüttet 177 Späte Rehabilitierung? Zeittafel 185 Auf Deutsch erschienene Bücher von Jean Ziegler 187 Bildnachweise 189 In dieser Zeit des revolutionären Umbruchs ging es bei den neuen Machthabern in Havanna noch recht informell zu und her. -

Localizing the Decent Work Agenda Through South-South and City-To-City Cooperation

Localizing the Decent Work Agenda through South-South and City-to-City Cooperation Department of Partnerships and Field Support International Labour Office Localizing the Decent Work Agenda through South-South and City-to-City Cooperation Department of Partnerships and Field Support International Labour Office Copyright © International Labour Organization 2015 First published 2015 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organisations may make copies in accordance with licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Localizing the Decent Work Agenda through South-South and City-to-City Cooperation, Geneva 2015 ISBN: 978-92-2-130321-3 (print) ISBN: 978-92-2-130322-0 (web pdf) ISBN: 978-92-2-030356-6 (CD-ROM) ILO Cataloguing in Publication Data The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rest solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. -

Independent Evaluation of the ILO's Strategy to Address HIV and AIDS and the World of Work /Carla Henry, Mei Zegers; International Labour Office, Evaluation Unit

Independent evaluation of the ILO’s strategy to address HIV and AIDS and the world of work For more information: International Labour Offi ce (ILO) Tel.: (+ 41 22) 799 6440 Evaluation Unit (EVAL) Fax: (+41 22) 799 6219 OCTOBER 2011 4, route des Morillons E-mail: [email protected] CH-1211 Geneva 22 http://www.ilo.org/evaluation Switzerland EVALUATION UNIT Independent evaluation of the ILO’s strategy to address HIV and AIDS and the world of work International Labour Office September 2011 Copyright © International Labour Organization 2011 First published 2011 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Henry, Carla; Zegers, Mei Independent evaluation of the ILO's strategy to address HIV and AIDS and the world of work /Carla Henry, Mei Zegers; International Labour Office, Evaluation Unit. - Geneva: ILO, 2011 1 v. ISBN print: 978-92-2-125422-5 -

And Trade Development Roadmap of the Gambia 2018-2022

Strategic Youth and Trade Development Roadmap of The Gambia 2018-2022 Republic of The Gambia STRATEGIC YOUTH AND TRADE DEVELOPMENT ROADMAP OF THE GAMBIA 2018-2022 Republic of The Gambia This Strategic Youth and Trade Development Roadmap (SYTDR ) was developed on the basis of the process, methodology and technical assistance of International Trade Centre (ITC ) within the framework of its Trade Development Strategy programme. ITC is the joint agency of the World Trade Organization and the United Nations. As part of ITC’s mandate of fostering sustain- able development through increased trade opportunities, the Chief Economist and Export Strategy section offers a suite of trade-related strategy solutions to maximize the development pay-offs from trade. ITC-facilitated trade development strategies and roadmaps are oriented to the trade objectives of a country or region and can be tailored to high-level economic goals, specific development targets or particular sectors, allowing policymakers to choose their preferred level of engagement. The views expressed herein do not reflect the official opinion of ITC. Mention of firms, products and product brands does not imply the endorsement of ITC. This document has not been formally edited by ITC. © International Trade Centre 2018 ITC encourages reprints and translations for wider dissemination. Short extracts may be freely reproduced, with due acknowledge- ment, using the suggestion citation. For more extensive reprints or translations, please contact ITC, using the online permission request form -

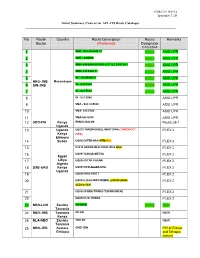

Initial Summary Content for AFI ATS Route Catalogue

APIRG/19 WP/14 Appendix 3.2D Initial Summary Content for AFI ATS Route Cataloque ____________________________________________________________________________________________ No Route Country Route Description Route Remarks . Sector (Preferred) Designator ICAO-ESAF 1 VBR - S15 40 E042 37 UT512 ASIO UPR 2 VBR – GADNO UT513 ASIO UPR VBR- S18 E041 13 VBR-S18 15.2 E041 04.1 ASIO UPR 3 UT515 4 VBR- S19 E040 37 UT516 ASIO UPR 5 VL - S19 E040 37 UT517 ASIO UPR HKG-JNB Mozambique 6 SIN-JNB VL- S20 E040 UT518 ASIO UPR 7 VL- S21 E040 UT519 ASIO UPR 8 IN - S21 E040 ASIO UPR 9 VMA - S23 30 E040 ASIO UPR 10 VMA- S25 E040 ASIO UPR 11 VMA-S26 E040 ASIO UPR 12 ADD-FIH Kenya EKBUL-NALOS RouteLab 1 Uganda 13 Uganda UQ579 TAREM-EKBUL-IMKIT-DWA (TAREM-DCT- iFLEX 2 Kenya DWA) Ethiopia 14 Sudan UQ583 KITEK-KNA-KTM-KSL iFLEX 2 15 UT419 ASKON-MLK-TIKAT-OHA QHA iFLEX 2 UQ597 DANAD-METSA iFLEX 2 16 Egypt 17 Libya UQ598 DITAR-PASAM iFLEX 2 Algeria 18 DXB-GRU Kenya UQ599 KFR-ALSEP-KHG iFLEX 2 Uganda 19 UQ595 KHG-KIRET iFLEX 2 20 UQ594 LIGAT-OWT-ORMOL-LOPID-UMINI- iFLEX 2 SEDVA-YEN 21 UQ596 IPOBA-TWARG-TUKAM-IMRAD iFLEX 2 22 UQ853 DJA-TWARG iFLEX 2 23 NBO-LUN Zambia KS-SINGI UT428 NEW Tanzania 24 NBO-JNB Tanzania NV-DO NEW Kenya 25 NLA-NBO Zambia VND-NV NEW Tanzania 26 NBO-JED Asmara GWZ-JDW FIR of Eritrea Ethiopia and Ethiopia closure APIRG/19 WP/14 Appendix 3.2D Initial Summary Content for AFI ATS Route Cataloque ____________________________________________________________________________________________ 27 ABV-SSG Nigeria BIMAT-ARDEX NEW No Route Country Route Description Remarks . -

Freedom from Want Advancing Human Rights Sumner B

freedom from want advancing human rights sumner b. twiss, john kelsay, terry coonan, series editors Breaking Silence: The Case That Changed the Face of Human Rights richard alan white For All Peoples and All Nations: The Ecumenical Church and Human Rights john s. nurser Freedom from Want: The Human Right to Adequate Food george kent freedom from want The Human Right to Adequate Food george kent foreword by jean ziegler georgetown university press washington, d.c. Georgetown University Press, Washington, D.C. © 2005 by Georgetown University Press. all rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 2005 This book is printed on acid-free, recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials and that of the Green Press Initiative. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kent, George, 1939– Freedom from want : the human right to adequate food / George Kent. p. cm. — (Advancing human rights series) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 1-58901-055-8 (cloth : alk. paper) — isbn 1-58901-056-6 (paper : alk. paper) 1. Food supply. 2. Hunger. 3. Human rights. I. Title. II. Series. hd9000.5.k376 2005 363.8—dc22 2004025023 Design and composition by Jeƒ Clark at Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services Dedicated to the hundreds of millions of people who suƒer because of what governments do, and fail to do. Creo que el mundo es bello, que la poesía es como el pan, de todos. I believe the world is beautiful and that poetry, like bread, is for everyone. -

THIRD WORLD Investment Accords Come Under Growing Scrutiny

EconomicsTHIRD WORLD TRENdS & ANAlySiS Published by the Third World Network KDN: PP 6946/07/2013(032707) ISSN: 0128-4134 Issue No 581 16 30 November 2014 Investment accords come under growing scrutiny More voices are being raised, not only in developing but in devel- oped countries as well, questioning the wisdom of signing trade and investment agreements which would allow foreign investors to sue governments in international tribunals. The increasing calls for a rethink of such treaties are prompted, among others, by concerns over bias and flaws in the so-called investor-state dispute settlement system. l Tide turns on investor treaties p2 l Investment treaties bring more risk than benefit p3 Also in this issue: Water services flowing back into Cosmetic changes to fundamen- public hands p9 tally flawed World Bank report p5 Analysis: TTIP may lead to EU Trade deals sow seeds of injustice dis-integration, unemployment, p7 instability p11 No 581 Third World Economics 16 30 November 2014 1 CURRENT REPORTS Investment agreements THIRD WORLD Economics Tide turns on investor treaties Trends & Analysis 131 Jalan Macalister The winds of change are blowing against trade and investment treaties 10400 Penang, Malaysia that contain the investor-sue-the-state system, which is now described as Tel: (60-4) 2266728/2266159 toxic by Western politicians and media. Fax: (60-4) 2264505 Email: [email protected] Website: www.twn.my by Martin Khor Contents The tide is turning against the controver- claiming many billions of euros of lost sial system in which foreign companies profits because of new German policies CURRENT REPORTS are allowed to sue governments of their to phase out nuclear power and to 2 Tide turns on investor treaties host countries in a foreign court for mil- tighten emissions regulations in power 3 Investment treaties bring more risk lions or billions of dollars. -

![THE TRICONTINENTAL[:Es]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8568/the-tricontinental-es-1168568.webp)

THE TRICONTINENTAL[:Es]

1 Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research international, movement-driven institution focused on stimulating intellectual debate that serves people’s aspirations. Without a Country in Which to Live, a Field to Plant, a Love to Cherish or a Voice to Sing, One is Dead: The Sixteenth Newsletter (2020). Tricontinental · Thursday, April 16th, 2020 Ελληνικά Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research - 1 / 11 - 04.10.2021 2 Gontran Guanaes Netto, O povo da terra dos papagaios (The people of the land of the parrots), 1982 Dear Friends, Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. Burkina Faso, in the Sahel region of the African continent, has been struck hard by the global pandemic; officially reported deaths from COVID-19 are second only to Algeria in Africa. In the past sixteen months, nearly 840,000 people out of twenty million have been displaced by conflict and drought; in March alone, 60,000 people were forced from their homes. Last year, the United Nations calculated that the number of Burkinabè residents who had little access to food was 680,000; this year, the UN estimates that the number will rise to 2.1 million. Conflict over resources and ideology had already greatly strained the region, where the climate catastrophe-generated desiccation of the Sahel has produced a serious agrarian crisis. No wonder that Xavier Creach, the Sahel coordinator of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) recently said: ‘Local communities have demonstrated remarkable Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research - 2 / 11 - 04.10.2021 3 generosity, but cannot cope anymore. National capacities are overwhelmed.