The Story of King Constant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

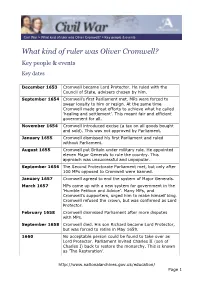

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Appendix 1: Monastic and Religious Foundations in Thirteenth-Centur Y

APPENDIX 1: MONASTIC AND RELIGIOUS FOUNDATIONS IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FLANDERS AND HAINAUT Affiliation: Arrouaise Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Eeckhout c. 1060/1146 Arrouaise Men Choques 1120/1138 Arrouaise Men Cysoing 855/1132 Arrouaise Men Phalernpin 1039/1145 Arrouaise Men Saint-Jean Baptiste c. 680/1142 Arrouaise Men Saint-Ni colas des Pres 1125/1140 Arrouaise Men Warneton 1066/1142 Arrouaise Men Zoetendale 1162/1215 re-founded Men Zonnebeke 1072/1142 Arrouaise Men Affiliation: Augustinian Canons Name Date of Foundation MenlWomen Saint-Aubert 963/1066 reforrned Men Saint-Marie, Voormezele 1069/1110 reforrned Men Saint-Martin, Ypres 1012/1102 reformed Men Saint-Pierre de Loo c. 1050/1093 reformed Men Saint-Pierre et Saint-Vaast c. 1091 Men Affiliation: Beguines Name Date cf Foundation MenlWomen Aardenburg 1249 Wornen Audenarde 1272 Wornen Bardonck, Y pres 1271/1273 Wornen Bergues 1259 Wornen 118 WOMEN, POWER, AND RELIGIOUS PATRONAGE Binehe 1248 Wornen Briel, Y pres 1240 Wornen Carnbrai 1233 Wornen Charnpfleury, Douai 1251 Wornen Damme 1259 Wornen Deinze 1273 Wornen Diksrnuide 1273 Wornen Ijzendijke 1276 Wornen Maubeuge 1273 Wornen Cantirnpre, Mons 1245 Wornen Orehies 1267 Wornen Portaaker (Ghent) 1273 Wornen Quesnoy 1246 Wornen Saint-Aubert (Bruges) 1270 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Courtrai) 1242 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Ghent) 1234 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Lilie) 1244/1245 Wornen Sainte-Elisabeth (Valeneiennes) 1239 Wornen Ter Hooie (Ghent) 1262 Wornen Tournai 1241 Wornen Wetz (Douai) 1245 Wornen Wijngaard (Bruges) 1242 Wornen Affiliation: Benedictine Name Date oJ Foundation Men/Women Anehin 1079 Men Notre-Darne d'Avesnes 1028 Wornen Bergues Saint-Winoe 1028 Men Bourbourg c. 1099 Wornen Notre-Darne de Conde e. -

Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019

16 March — 14 July 2019 British Royal Portraits Exhibition organised by the National Portrait Gallery, London Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019 Tudors to Windsors traces the history of the British monarchy through the outstanding collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London. This exhibition highlights major events in British (and world) history from the sixteenth century to the present, examining the ways in which royal portraits were impacted by both the personalities of individual monarchs and wider historical change. Presenting some of the most significant royal portraits, the exhibition will explore five royal dynasties: the Tudors, the Stuarts, the Georgians, the Victorians and the Windsors shedding light on key figures and important historical moments. This exhibition also offers insight into the development of British art including works by the most important artists to have worked in Britain, from Sir Peter Lely and Sir Godfrey Kneller to Cecil Beaton and Annie Leibovitz. 2 UK WORLDWIDE 1485 Henry Tudor defeats Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field, becoming King Henry VII The Tudors and founding the Tudor dynasty 1492 An expedition led by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus encounters the Americas 1509 while searching for a Western passage to Asia Henry VII dies and is succeeded Introduction by King Henry VIII 1510 The Inca abandon the settlement of Machu Picchu in modern day Peru Between 1485 and 1603, England was ruled by 1517 Martin Luther nails his 95 theses to the five Tudor monarchs. From King Henry VII who won the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, crown in battle, to King Henry VIII with his six wives and a catalyst for the Protestant Reformation 1519 Elizabeth I, England’s ‘Virgin Queen’, the Tudors are some Hernando Cortes lands on of the most familiar figures in British history. -

Literature Review the Outline of My Research Topic Will Encompass

Literature Review The outline of my research topic will encompass Anne of Denmark’s role as queen consort in Scotland and England, from 1589 to 1619, in order to investigate her political influence. To fully understand Anna’s political role, recent historiography surrounding influential women in early modern England and, in particular, the role of the queen consort will be evaluated in depth. My research will contribute to these two growing fields and fill a gap by re-examining Anna, who historians once considered frivolous and vain. Accompanied by re-definitions of high politics at one end of the spectrum and court masques at the other, a re-assessment of her character throughout her reign as queen consort of Scotland and England is accordingly needed. The value of analysing Anna in a political light will be demonstrated in this essay through an examination of the historiography surrounding influential women in early modern England, queen consorts in general and then Anna herself. Previous study has excluded women from high politics because it was considered part of the public sphere, rather than the private sphere that they belonged to. In her article ‘Women and Politics in Early Tudor England’, Harris challenges the traditional view of high politics by emphasising its redefinition to include the influence of women.1 Sara Mendelson and Patricia Crawford’s book, Women in Early Modern England, echoes this view. Although women exercised some influence in high politics, this is not 1 B. Harris., ‘Women and Politics in Early Tudor England’, The Historical Journal, 33:2 (1990), pp.259-281, p.259. -

Monarchs During Feudal Times

Monarchs During Feudal Times At the very top of feudal society were the monarchs, or kings and queens. As you have learned, medieval monarchs were also feudal lords. They were expected to keep order and to provide protection for their vassals. Most medieval monarchs believed in the divine right of kings, the idea that God had given them the right to rule. In reality, the power of monarchs varied greatly. Some had to work hard to maintain control of their kingdoms. Few had enough wealth to keep their own armies. They had to rely on their vassals, especially nobles, to provide enough knights and soldiers. In some places, especially during the Early Middle Ages, great lords grew very powerful and governed their fiefs as independent states. In these cases, the monarch was little more than a figurehead, a symbolic ruler who had little real power. In England, monarchs became quite strong during the Middle Ages. Since the Roman period, a number of groups from the continent, including Vikings, had invaded and settled England. By the mid11th century, it was ruled by a Germanic tribe called the Saxons. The king at that time was descended from both Saxon and Norman (French) families. When he died without an adult heir, there was confusion over who should become king. William, the powerful Duke of Normandy (a part of presentday France), believed he had the right to the English throne. However, the English crowned his cousin, Harold. In 1066, William and his army invaded England. William defeated Harold at the Battle of Hastings and established a line of Norman kings in England. -

Castellan Comes in Two Editions: One with Red and Blue Keeps and That Will Be Easy for Your Opponent to Complete

Strategy Playing With 3 or 4 Players TM First and foremost: try not to leave almost-finished courtyards Castellan comes in two editions: one with red and blue Keeps and that will be easy for your opponent to complete. The more cards he rules in English only, and the other with yellow and green Keeps and has in his hand, the more dangerous rules in five languages. he is! By combining the red/blue and the yellow/green sets, you can play Beware the temptation to spend Castellan with three or four. (So if one of your friends already has this your whole hand at once. You only Score: 6 game, you should buy the other version!) get one new card at the end of each There are very few rule changes for multi-player games: turn. This means that if you use most Determine the starting player randomly. Turns pass to the left. or all of your cards together to get a If you cannot use a piece, hand it to the player to your left. super-build turn, your hand will be The game changes a great deal (and becomes longer) if the players down to a single card until a “draw can negotiate and make deals about where they will build. We extra card” symbol comes up. A recommend against deal-making unless everyone is familiar with Become the master of the castle . single card may not give you good the game. options . but you must still play a A courtyard with As far as strategy goes: in a multi-player game, it is harder to plan Your Mission card every turn. -

Ana Turri Gimilli

UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA « LA SAPIENZA » DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE STORICHE ARCHEOLOGICHE E ANTROPOLOGICHE DELL’ANTICHITÀ SEZIONE VICINO ORIENTE QUADERNO V ana turri gimilli studi dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer, S.J. da amici e allievi R O M A 2 0 1 0 VICINO ORIENTE – QUADERNO V ana turri gimilli studi dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer, S.J. da amici e allievi a cura di M.G. Biga – M. Liverani ROMA 2010 VICINO ORIENTE Annuario del Dipartimento di Scienze Storiche Archeologiche e Antropologiche dell’Antichità - Sezione Vicino Oriente I-00185 Roma - Via Palestro, 63 Comitato Scientifico : M.G. Amadasi, A. Archi, M. Liverani, P. Matthiae, L. Nigro, F. Pinnock, L. Sist Redazione : L. Romano, G. Ferrero Copertina : Disegno di L. Romano da Or 75 (2006), Tab. XII La foto di Padre Mayer è di Padre F. Brenk UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA «L A SAPIENZA » SOMMARIO Presentazione 3 M.G. Amadasi Guzzo - Encore hypothèses à Karatepe 7 L. Barbato - Esarhaddon, Na’id-Marduk e gli šībūtu del Paese del Mare 23 M.G. Biga - War and Peace in the Kingdom of Ebla (24 th Century B.C.) in the First Years of Vizier Ibbi-zikir under the Reign of the Last King Išar-damu 39 F. D’Agostino - Due nuovi testi dal British Museum datati all’epoca più antica di Ur III 59 P. Dardano - La veste della sera: echi di fraseologia indoeuropea in un rituale ittito-luvio 75 G.F. Del Monte - Su alcune tecniche contabili delle amministrazioni di Nippur medio-babilonese 85 F. Di Filippo - Two Tablets from the Vicinity of Emar 105 F.M. -

The Swedish Monarchy

Facts about Sweden: Monarchy sweden.se The Swedish monarchy Sweden’s head of state is King Carl XVI Gustaf. In 1980, Sweden became the first monarchy to change its succession rites so that the first- born child of the monarch is heir to the throne, regardless of gender. Heir apparent to the Swedish throne is Crown Princess Victoria. Sweden is one of the world’s most stable and Carl XVI Gustaf egalitarian democracies, with a monarchy King Carl XVI Gustaf is the seventh monarch that has strong roots. of the House of Bernadotte. He was born As head of state, the King is Sweden’s fore- on 30 April 1946 as the fifth child and only Clockwise from left: Crown most unifying symbol. According to the 1974 son of Hereditary Prince Gustaf Adolf and Princess Victoria, heir apparent; constitution, the monarch has no political Princess Sibylla. Hereditary Prince Gustaf King Carl XVI Gustaf, head of state; Princess Estelle, second power or affinity. The King’s duties are of Adolf died in an airplane crash in Denmark in line to the Swedish throne. a ceremonial and representative nature. the following year. Photo: Sandra Birgersdotter Sandra Ek/Royal Sweden CourtPhoto: of Facts about Sweden: Monarchy sweden.se In 1950, Carl Gustaf became Crown Prince since he took part in the UN Conference on of Sweden when his great-grandfather the Human Environment – the first of its kind The Royal Palace Gustaf V died and was succeeded by the – in Stockholm back in 1972. The Royal Palace of Stockholm is the then 68-year-old Gustaf VI Adolf, the Crown He is likewise deeply committed to the King's official residence. -

His Royal Highness King Abdullah II Bin Al-Hussein of the Hashemite

His Royal Highness King Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein Of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Remarks to The Washington Institute for Near East Policy Honoring Reuven Rivlin, President of the State of Israel Scholar-Statesman Award Virtual Gala November 19, 2020 Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim, [in the name of God, the merciful and compassionate.] Dear friends, My thanks to Rob [Satloff, executive director of The Washington Institute] and the Washington Institute team for inviting me to be a part of this special event. My greetings to all attendees at this virtual gathering. I still fondly remember the wonderful evening we spent in New York last year when I was humbled to receive the Scholar-Statesman Award. And today, I extend my congratulations to this year's recipient of the honor, President Rivlin. At a time when not only our region but our world is plagued by illness and strife, it is courage, leadership, and partnerships that are needed now more than ever to overcome differences and to bring us all closer to healthier, safer, and more peaceful shores. Jordan has always believed in peace for the Palestinians and the Israelis as the only way forward for the region. We will never give up on this hope for our neighbors or for our neighborhood. And it is in this vein, and using this occasion and form of dialogue, that I pledge once again to continue to do everything possible to achieve the just and lasting peace that fulfills the aspirations of all sides on the basis of a two-state solution. -

The Zhou Dynasty Around 1046 BC, King Wu, the Leader of the Zhou

The Zhou Dynasty Around 1046 BC, King Wu, the leader of the Zhou (Chou), a subject people living in the west of the Chinese kingdom, overthrew the last king of the Shang Dynasty. King Wu died shortly after this victory, but his family, the Ji, would rule China for the next few centuries. Their dynasty is known as the Zhou Dynasty. The Mandate of Heaven After overthrowing the Shang Dynasty, the Zhou propagated a new concept known as the Mandate of Heaven. The Mandate of Heaven became the ideological basis of Zhou rule, and an important part of Chinese political philosophy for many centuries. The Mandate of Heaven explained why the Zhou kings had authority to rule China and why they were justified in deposing the Shang dynasty. The Mandate held that there could only be one legitimate ruler of China at one time, and that such a king reigned with the approval of heaven. A king could, however, loose the approval of heaven, which would result in that king being overthrown. Since the Shang kings had become immoral—because of their excessive drinking, luxuriant living, and cruelty— they had lost heaven’s approval of their rule. Thus the Zhou rebellion, according to the idea, took place with the approval of heaven, because heaven had removed supreme power from the Shang and bestowed it upon the Zhou. Western Zhou After his death, King Wu was succeeded by his son Cheng, but power remained in the hands of a regent, the Duke of Zhou. The Duke of Zhou defeated rebellions and established the Zhou Dynasty firmly in power at their capital of Fenghao on the Wei River (near modern-day Xi’an) in western China.