Sexual Orientation and the Second to Fourth Finger Length Ratio: a Meta-Analysis in Men and Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexual Differentiation of the Vertebrate Nervous System

T HE S EXUAL B RAIN REVIEW Sexual differentiation of the vertebrate nervous system John A Morris, Cynthia L Jordan & S Marc Breedlove Understanding the mechanisms that give rise to sex differences in the behavior of nonhuman animals may contribute to the understanding of sex differences in humans. In vertebrate model systems, a single factor—the steroid hormone testosterone— accounts for most, and perhaps all, of the known sex differences in neural structure and behavior. Here we review some of the events triggered by testosterone that masculinize the developing and adult nervous system, promote male behaviors and suppress female behaviors. Testosterone often sculpts the developing nervous system by inhibiting or exacerbating cell death and/or by modulating the formation and elimination of synapses. Experience, too, can interact with testosterone to enhance or diminish its effects on the central nervous system. However, more work is needed to uncover the particular cells and specific genes on which http://www.nature.com/natureneuroscience testosterone acts to initiate these events. The steps leading to masculinization of the body are remarkably con- Apoptosis and sexual dimorphism in the nervous system sistent across mammals: the paternally contributed Y chromosome Lesions of the entire preoptic area (POA) in the anterior hypothala- contains the sex-determining region of the Y (Sry) gene, which mus eliminate virtually all male copulatory behaviors3,whereas induces the undifferentiated gonads to form as testes (rather than lesions restricted to the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the POA (SDN- ovaries). The testes then secrete hormones to masculinize the rest of POA) have more modest effects, slowing acquisition of copulatory the body. -

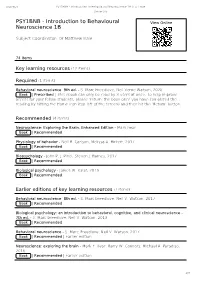

PSY1BNB - Introduction to Behavioural Neuroscience 1B | La Trobe University

09/27/21 PSY1BNB - Introduction to Behavioural Neuroscience 1B | La Trobe University PSY1BNB - Introduction to Behavioural View Online Neuroscience 1B Subject Coordinator: Dr Matthew Hale 74 items Key learning resources (12 items) Required (1 items) Behavioral neuroscience 9th ed. - S. Marc Breedlove, Neil Verne Watson, 2020 Book | Prescribed | This ebook can only be read by 3 users at once. To help improve access for your fellow students, please ‘return’ the book once you have completed the reading by hitting the Home icon (top left of the screen) and then hit the ‘Return’ button. Recommended (4 items) Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain, Enhanced Edition - Mark Bear Book | Recommended Physiology of behavior - Neil R. Carlson, Melissa A. Birkett, 2017 Book | Recommended Biopsychology - John P. J. Pinel, Steven J. Barnes, 2017 Book | Recommended Biological psychology - James W. Kalat, 2019 Book | Recommended Earlier editions of key learning resources (7 items) Behavioral neuroscience 8th ed. - S. Marc Breedlove, Neil V. Watson, 2017 Book | Recommended Biological psychology: an introduction to behavioral, cognitive, and clinical neuroscience - 7th ed. - S. Marc Breedlove, Neil V. Watson, 2013 Book | Recommended Behavioral neuroscience - S. Marc Breedlove, Neil V. Watson, 2017 Book | Recommended | Earlier edition Neuroscience: exploring the brain - Mark F. Bear, Barry W. Connors, Michael A. Paradiso, 2016 Book | Recommended | Earlier edition 1/8 09/27/21 PSY1BNB - Introduction to Behavioural Neuroscience 1B | La Trobe University Physiology of behavior - Neil R. Carlson, c2013 Book | Recommended | Earlier edition Biopsychology - John P. J. Pinel, 2014 Book | Recommended | Earlier edition Biological psychology - James W. Kalat, 2013 Book | Recommended | Earlier edition Sensory Systems (13 items) Weeks 1 - 5 Week 1: General and Chemical Senses (1 items) Behavioral neuroscience [Selected pages] Chapter | Prescribed | Essential reading: pp. -

Individual Differences in the Biological Basis of Androphilia in Mice And

Hormones and Behavior 111 (2019) 23–30 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Hormones and Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yhbeh Review article Individual differences in the biological basis of androphilia in mice and men T ⁎ Ashlyn Swift-Gallant Neuroscience Program, Michigan State University, 293 Farm Lane, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA Department of Psychology, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NL A1B 3X9, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: For nearly 60 years since the seminal paper from W.C Young and colleagues (Phoenix et al., 1959), the principles Androphilia of sexual differentiation of the brain and behavior have maintained that female-typical sexual behaviors (e.g., Transgenic mice lordosis) and sexual preferences (e.g., attraction to males) are the result of low androgen levels during devel- Androgen opment, whereas higher androgen levels promote male-typical sexual behaviors (e.g., mounting and thrusting) Sexual behavior and preferences (e.g., attraction to females). However, recent reports suggest that the relationship between Sexual preferences androgens and male-typical behaviors is not always linear – when androgen signaling is increased in male Sexual orientation rodents, via exogenous androgen exposure or androgen receptor overexpression, males continue to exhibit male- typical sexual behaviors, but their sexual preferences are altered such that their interest in same-sex partners is increased. Analogous to this rodent literature, recent findings indicate that high level androgen exposure may contribute to the sexual orientation of a subset of gay men who prefer insertive anal sex and report more male- typical gender traits, whereas gay men who prefer receptive anal sex, and who on average report more gender nonconformity, present with biomarkers suggestive of low androgen exposure. -

PSYC 3458 36474 Biopsych Syllabus

Biological Psychology Spring 2016 Instructor: Jamie G. Bunce, PhD Email: [email protected] *Email is the best way to reach me. Phone: 617-373-6327 Office hours: Tuesday 10:00-11:00 AM; Wednesday 3:00-4:00 PM; Friday 9:00-10:00 AM and by email appointment. Office: 382 Nightingale Hall (Please use the black phone at the entrance to the 3rd floor to dial my extension [x6327] and I will escort you to the office). Class: PSYC 3458, CRN 36474, Section 02; Mon. Wed. &Thurs. 9:15-10:20 AM; Shillman Hall, Room 305. Prerequisites: PSYC 1101 Course Description: We will explore the structures and systems of the brain and how these relate to behavior as well as the methods and theories which provide insight into biobehavioral processes. This course will cover a variety of topics ranging from cellular processes to the emergent function of neural systems. We will also investigate how the nervous system is affected by substances including hormones, pharmacological therapeutics and recreational drugs. In addition we will examine neurological disorders and their treatment. Learning Outcomes: • Students should be able to state examples of theoretical perspectives and major findings across broad areas of neuroscience, e.g., anatomical, behavioral, developmental, clinical, comparative, and computational. • Students should be able to demonstrate a depth of knowledge in self-selected areas of study in behavioral neuroscience and develop testable research questions based upon this knowledge. • Students should be able to relate behavioral neuroscience with other disciplines, e.g., computer science, theoretical physics, health sciences, sport and society, sociology. -

Male Homosexuality and Maternal Immune Responsivity to the Y-Linked Protein NLGN4Y

Male homosexuality and maternal immune responsivity to the Y-linked protein NLGN4Y Anthony F. Bogaerta,b,1, Malvina N. Skorskab,c, Chao Wangd, José Gabriea, Adam J. MacNeila, Mark R. Hoffarthb, Doug P. VanderLaanc,e, Kenneth J. Zuckerf, and Ray Blanchardf aDepartment of Health Sciences, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON L2S 3A1, Canada; bDepartment of Psychology, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON L2S 3A1, Canada; cDepartment of Psychology, University of Toronto Mississauga, Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6, Canada; dBrigham & Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; eChild, Youth and Family Division, Underserved Populations Research Program, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, ON M6J 1H4, Canada; and fDepartment of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5T 1R8, Canada Edited by S. Marc Breedlove, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Thomas D. Albright October 23, 2017 (received for review April 8, 2017) We conducted a direct test of an immunological explanation of the resulting in death of the affected cells or inducing miscarriage). finding that gay men have a greater number of older brothers Both PCDH11Y and NLGN4Y are part of families of cell ad- than do heterosexual men. This explanation posits that some hesion molecules thought to play an essential role in specific mothers develop antibodies against a Y-linked protein important cell–cell interactions in brain development (23). in male brain development, and that this effect becomes increas- In our study, blood samples and reproductive histories were ingly likely with each male gestation, altering brain structures un- collected from 54 mothers of gay sons (23 of whom had pre- derlying sexual orientation in their later-born sons. -

Male Homosexuality and Maternal Immune Responsivity to the Y-Linked Protein NLGN4Y

Male homosexuality and maternal immune responsivity to the Y-linked protein NLGN4Y Anthony F. Bogaerta,b,1, Malvina N. Skorskab,c, Chao Wangd, José Gabriea, Adam J. MacNeila, Mark R. Hoffarthb, Doug P. VanderLaanc,e, Kenneth J. Zuckerf, and Ray Blanchardf aDepartment of Health Sciences, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON L2S 3A1, Canada; bDepartment of Psychology, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON L2S 3A1, Canada; cDepartment of Psychology, University of Toronto Mississauga, Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6, Canada; dBrigham & Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; eChild, Youth and Family Division, Underserved Populations Research Program, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, ON M6J 1H4, Canada; and fDepartment of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5T 1R8, Canada Edited by S. Marc Breedlove, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Thomas D. Albright October 23, 2017 (received for review April 8, 2017) We conducted a direct test of an immunological explanation of the resulting in death of the affected cells or inducing miscarriage). finding that gay men have a greater number of older brothers Both PCDH11Y and NLGN4Y are part of families of cell ad- than do heterosexual men. This explanation posits that some hesion molecules thought to play an essential role in specific mothers develop antibodies against a Y-linked protein important cell–cell interactions in brain development (23). in male brain development, and that this effect becomes increas- In our study, blood samples and reproductive histories were ingly likely with each male gestation, altering brain structures un- collected from 54 mothers of gay sons (23 of whom had pre- derlying sexual orientation in their later-born sons. -

KALIRIS SALAS-RAMIREZ, PH.D. the Sophie Davis School For

KALIRIS SALAS‐RAMIREZ, PH.D. The Sophie Davis School for Biomedical Education ‐ CUNY Medical School, Department of Physiology, Pharmacology, and Neuroscience 160 Convent Ave, New York, NY 10031 | office 212‐650‐8255, fax 212‐650‐7726 | [email protected] EMPLOYMENT The Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education – CUNY Medical School The City College of New York Assistant Medical Professor Aug 2011 ‐ present Research Assistant Professor Feb 2011 – July 2011 EDUCATION The Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education – CUNY Medical School The City College of New York Post Doctoral Research Assistant 2008 ‐ 2011 Advisor: Dr. Eitan Friedman; Collaborator and Mentor: Dr. Victoria Luine (Hunter College, CUNY) Research focus: The effects of prenatal and adolescent cocaine on the developing brain and behavior, specifically cognition, addiction and neuronal plasticity. Michigan State University Ph.D. in Neuroscience 2001‐2007 Dissertation: Adolescent Anabolic Steroid Exposure: Social Behaviors and Neural Plasticity Advisor: Dr. Cheryl Sisk Graduate Guidance Committee: Dr. S. Marc Breedlove, Dr. Antonio Nunez and Dr. David Kreulen Research focus: Organizational and activational effects of gonadal hormones during adolescence, anabolic steroids, social behavior and neural plasticity University of Puerto Rico – Río Piedras Campus Graduate Student, MS level Advisor: Dr. Carmen Maldonado‐Vlaar 2000‐2001 Research focus: Neurobiology of drug addiction and behavioral psychopharmacology, interactions between dopamine and glutamate receptors University of Puerto Rico – Mayagüez Campus BS in Biology 1996‐2000 Equivalent to a minor: Psychology Honors: Magna Cum Laude AWARDS/HONORS NHSN Early Career Pilot Award June 2011 Travel award to attend the Society for Neuroscience from CUNY November 2010 Graduate Center Travel Award for FASEB/MARC Leadership Development August 2009 And Grant Writing Workshop KALIRIS SALAS‐RAMIREZ, PH.D. -

Greenspan's Basic and Clinical En

YALE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE 85 (2012), pp.559-565. Copyright © 2012. Book Reviews Greenspan’s Basic and Clinical En - docrinology. Ninth Edition. By David G. Since the authors do not assume that Gardner and Dolores Shoback. China: readers have any previous knowledge of the McGraw-Hill Medical; 2011. 880 pp. US topics, they begin each topic with explana - $57 Paperback. ISBN: 978-0071622431. tions of basic concepts. Easy-to-read with clear illustrations, thorough foundation, and In Greenspan’s Basic and Clinical En - research-based clinically relevant novel de - docrinology , the authors of each chapter velopments in endocrinology, the enduring succinctly develop complex physiological nature of material presented in this book processes mediated by the endocrine sys - makes it a useful resource to experienced tem. Two additional chapters on obesity and medical practitioners as well as novices. endocrine hypertension have been included in this edition of the textbook. These chap - Asha Jayakumar, PhD ters are extremely useful in educating med - Yale University ical professionals to tackle obesity and hypertension by understanding the science The Mind's Machine: Foundations of behind it. Expertise in these diseases is nec - Brain and Behavior. By Neil V. Wat - essary, owing to the soaring numbers of son and S. Marc Breedlove. Sunder - obese and hypertensive patients. Hence, an land, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; entire chapter (Chapter 10) has been de - 2012. 453 pp. US $119.95 Paperback. voted to endocrine hypertension; however, ISBN: 978-0878939336. pheocytochroma, which manifests hyper - tension as one of the symptoms, is not men - The Mind's Machine: Foundations of tioned. -

Making the Gendered Face: the Art and Science of Facial Feminization Surgery

Making the Gendered Face: The Art and Science of Facial Feminization Surgery By Eric Douglas Plemons A dissertation completed in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge Professor Cori Hayden, Chair Professor Lawrence Cohen Professor Charis Thompson Spring 2012 Abstract Making the Gendered Face: The Art and Science of Facial Feminization Surgery By Eric Douglas Plemons Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Cori Hayden, Chair Early surgical procedures intended to change a person’s sex focused on the genitals as the site of a body’s maleness or femaleness, and took the reconstruction of these organs as the means by which “sex” could be changed. However, in the mid-1980s a novel set of techniques was developed in order to change a part of the body that proponents claim plays a more central role in the assessment and attribution of sex in everyday life: the face. Facial Feminization Surgery (FFS)—a set of bone and soft tissue surgical procedures intended to feminize the faces of male-to-female transsexuals—is predicated upon the notion that femininity is a measurable quality that can be both reliably assessed and surgically reproduced. Such an assertion begs the questions: What does a woman look like? What forms of knowledge are used to support a claim to know? This project examines these questions through ethnographic research situated in the offices and operating rooms of prominent American surgeons who perform FFS. I explore the tensions between two different forms of knowledge that surgeons rely on and appeal to in the identification and surgical reproduction of femininity: scientific and aesthetic. -

Through a Glass, Darkly Human Digit Ratios Reflect Prenatal Androgens

Hormones and Behavior 120 (2020) 104686 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Hormones and Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yhbeh Review article Through a glass, darkly: Human digit ratios reflect prenatal androgens, ☆ imperfectly T ⁎ Ashlyn Swift-Gallanta, Brandon A. Johnsonb, Victor Di Ritab, S. Marc Breedloveb,c, a Department of Psychology, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. Johns, NL A1B 3X9, Canada b Neuroscience Program, Michigan State University, United States of America c Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, United States of America ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: On average, the length of the index finger (digit 2) divided by the length of the ring finger (digit 4) on the right Digit ratios hand, is greater in women than in men. Converging evidence makes it clear that prenatal androgens affect the 2D:4D development of digit ratios in humans and so are likely responsible for this sex difference. Thus, differences in Androgen 2D:4D between groups within a sex may be due to average differences between those groups in prenatal an- Sexual orientation drogen exposure. There have been many reports that lesbians, on average, have a smaller (more masculine) digit Lesbians ratio than straight women, which has been confirmed by metaanalysis. These findings indicate that lesbians Organizational hypothesis Humans were, on average, exposed to greater prenatal androgen than straight women, which further indicates that greater levels of prenatal androgen predispose humans to be attracted to women in adulthood. Nevertheless, these results only apply to group differences between straight women and lesbians; digit ratios cannot be used to classify individual women as gay or straight. -

The LGBT News

Lansing’s LGBT Connection! Lansing Association for Human Rights The LGBT News Michigan’s oldest community based organization! October 2012 : Volume 34 : Issue 1 : Published Monthly A Matter of Law by Pam Sisson, Attorney & Mediator Voting in 2012 There are lots of folks who came before us who Hung in there long enough for you and me Maybe we just owe it to the next ones To ride this raging river out to sea From Cowboy, music and lyrics by Pam Sisson (1984) Grant Littke introducing Kiara Farrell-Starling, the Pride Scholarship recipient, at the successful 2011 Homecoming party. What an exciting time to be an American! Via It’s Time to Party!! this election, we will broadcast to the world who we are and what we really care about. Everyone is invited to the LGBT MSU Homecoming party / Everything is at stake. This is not the time to reception on Friday, October 12, 2012. The party will be held at the be silent. When I think about it, Democrats Kellogg Center in the spacious Red Cedar Room with fireplace after are often silent. Without analyzing that the MSU Homecoming Parade from 6:30 to 9:30. Whether you are behavior, it has got to change! Each of us has friends of MSU, alumni, students, or faculty /staff – we even hope to a voice and our government will flow in one have some guests from the University of Iowa – everyone is invited!! of two vastly different directions, depending on whether we speak out and how we vote. This fun event, the seventh annual, will include excellent food, including a chef I am concerned about the disempowerment carving the beef (do not eat dinner in advance), a cash bar including soda, free (and sometimes disenfranchisement) of many coffee, our beautiful green, white & purple décor, background music, and the Americans. -

Androgen Alters the Dendritic Arbors of SNB Motoneurons by Acting Upon Their Target Muscles

The Journal of Neuroscience, June 1995, 15(6): 4406-4416 Androgen Alters the Dendritic Arbors of SNB Motoneurons by Acting upon Their Target Muscles Mark N. Rand” and S. Marc Breedlove Department of Psychology and Graduate Groups in Neurobiology and Endocrinology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-l 650. In adult male rats, motoneurons of the spinal nucleus of 1983; Nordeen et al., 1985), which also masculinize the muscle the bulbocavernosus (SNB) have been shown to retract targets. In adult males, reduced systemic androgens are accom- and reextend their dendritic branches in response to sys- panied by decreases in SNB soma size (Breedlove and Arnold, temic androgen deprivation and readministration. Further- 198 I), size and number of synapses upon SNB somas and prox- more, other studies have suggested that the dendritic com- imal dendrites (Leedy et al., 1987), dendritic extent (Kurz et al., plexity of neurons can be regulated by their targets. To as- 1986; Forger and Breedlove, 1987; Sasaki and Arnold, 1991), sess whether androgens might act upon the target muscles and BC/LA muscle mass (Venable, 1966). Androgen receptors to mediate changes in SNB dendrites, adult male rats were are present in SNB motoneurons (Breedlove and Arnold, I980), castrated and implanted with a small capsule filled with BC/LA muscles (Jung and Baulieu, 1973), and supraspinal af- testosterone (T) next to the bulbocavernosus and levator ferents (Monaghan and Breedlove, 1991). It is not known which ani muscle complex (BC/LA) on one side, while the mus- of these tissues androgens might act upon to induce changes in cles on the contralateral side were implanted with another SNB motoneuron morphology.