A History of Doha and Bidda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cerimã³nia Partida Regresso.Xlsx

Date: 2020-02-21 Time: 09:00 Subject: CoC COMMUNICATION No: 1 Document No: 3:1 From: The Clerk of the Course To: All competitors / crew members Number of pages: 4 Attachments: 1 Notes: FIA SR = 2020 FIA Cross-Country Rally Sporting Regulations QCCR SR = 2020 Manateq Qatar Cross-Country Rally Supplementary Regulations 1. TIMECARD 0 At the reception of administrative checks each crew will receive a timecard which must be used for the following controls: • Administrative checks • Scrutineering • Ceremonial Start holding area IN • Rally Start holding area IN 2. ON-BOARD CAMERAS See article 11 of FIA SR. Competitors wishing to use a camera must supply the following information to the Organizer, in writing, during administrative checks: • Car number • Competitor’s name • Competitor’s address • Use of footage All camera positions and mountings used must be shown and approved during pre-event scrutineering. It is forbidden to mount cameras on the outside of the car. 3. ELECTRONIC EQUIPMENT See article 9 of FIA SR. Any numbers of telephones, mobile phones or satellite phones carried on board must be given to the Organiser during the administrative checks. 4. EQUIPMENT OF THE VEHICLES / “SOS/OK” sign Each competing vehicle shall carry a red “SOS” sign and on the reverse a green “OK” sign measuring at least 42 cm x 29.7 cm (A3). The sign must be placed in the vehicle and be readily accessible for both drivers. (article 48.2.5 of FIA SR). 5. CEREMONIAL START HOLDING AREA (Saturday / Souq Waqif) See article 10.2 of QCCR SR. Rally cars must enter the holding area at Souq Waqif during the time window shown in the rally programme (18.15/18.45h). -

Mandarin Oriental Doha Gets ISO 22000 for Food Safety Standards

04 Thursday, September 10, 2020 Nation Closure on Civil Defence QA launches 100th aircraft to feature Intersection, Al Rumeila high-speed ‘Super Wi-Fi’ connectivity Street and Onaiza Street THE Public Works Author- During the closure, motor- QA now offers the largest number of aircraft equipped with high-speed broadband on board in Asia and MENA ity (Ashghal) will temporar- ists coming from Wadi Al Sail ily close part of Onaiza Street or Onaiza Streets and wishing TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK in the direction from the Civil to go to Gulf Interchange will DOHA Defence Intersection towards be required to continue on Mo- Gulf Interchange at 500 meters hamed Bin Thani Street then QATAR Airways (QA) is cele- before the Gulf Interchange on turn left towards Sahim Bin brating the launch of its 100th September 11 and 12. Hamad Street then turn left to- aircraft to feature high-speed Ashghal will also close part wards Al Rayyan Road to reach ‘Super Wi-Fi’ connectivity, of the Civil Defence Intersec- Gulf Interchange and continue enabling passengers to stay tion in the same direction for towards their destinations. in touch with families, friends road users wishing to continue Motorists coming from Al and colleagues while on board straight on Onaiza Street to- Bidda Street and wishing to using the fastest broadband wards the Gulf Interchange, as turn right towards Al Rumeila service available in the sky. well as for those wishing to turn Street, will be required to con- With its 100th Super Wi- left from Mohamed Bin Thani tinue straight towards Al Bidda Fi enabled aircraft, Qatar Air- Street towards Onaiza Street. -

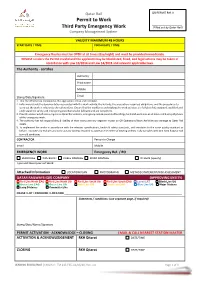

Permit to Work ______Third Party Emergency Work (Filled out by Qatar Rail) Company Management System

Qatar Rail QR-PERMIT Ref. # Permit to Work ____________________ Third Party Emergency Work (Filled out by Qatar Rail) Company Management System VALIDITY MAXIMUM 48 HOURS START DATE / TIME: FINISH DATE / TIME: Emergency Routes must be OPEN at all times (day/night) and must be provided immediately. MISUSE renders the Permit invalid and the applicant may be blacklisted, fined, and legal actions may be taken in accordance with Law 10/2014 and Law 14/2015 and relevant applicable laws. The Authority - certifies Authority Print name Mobile Email Stamp/Date/Signature 1. That the information contained in this application is true and complete. 2. Fully understands the documentation associated with this work activity, the hazards, the precautions required, obligations, and the procedures to carry out the work in relation to the rail interface. Ensure that the workforce undertaking the work activities are fully briefed, equipped, qualified and understand the safety and emergency procedures to be followed and are competent. 3. Provide unobstructed access/egress to Qatar Rail stations, emergency exits & associated buildings, land and work sites at all times and during all phases of the emergency work. 4. The authority has full responsibility & liability of their works and any negative impact on QR Operations/Work Activities and damage to Qatar Rail assets. 5. To implement the works in accordance with the relevant specifications, health & safety standards, and reinstates to the same quality standard as before. Excavate any trial pits and carry out any surveys required to ascertain the extent of existing utilities. Fully complies with QCS 2014 & Qatar Rail terms & conditions. CONTRACTOR Person in Charge Email Mobile EMERGENCY WORK Emergency Ref. -

Abdulla Storms to Fastest Time in Abu Dhabi, Confirms Second Spot

SPORT Friday 30 March 2018 PAGE | 22 PAGE | 23 PAGE | 24 Full-strengthFul Al Sadd Australian cricket Del Potro grindsnds pprepare for Al Wasl coach quits, captain down Raonic in clash breaks down in tears Miami Abdulla storms to fastest time in Abu Dhabi, confirms second spot THE PENINSULA Adel said: “We pushed from the start today and decided to ABU DHABI: Qatar’s Adel take a risk. Suddenly we saw Abdulla confirmed second Shegawi. I think he had a flat tyre position in the T2 standings at the or something. We pass him and Abu Dhabi Desert Challenge with I pushed very hard to the end of the fastest time in the final the stage.” 218.57km selective section from “I was pushing the maximum Hameem to the south of Abu of the car. I didn’t even slow Dhabi yesterday. down when the engine temper- Driving a rented Nissan ature went a bit higher. Some Safari Y61 in insipid heat, the sections today were open and fast Qatar’s Adel Abdulla Qatari and navigator Nasser Al and, maybe, that helped to cool (right) and navigator Kuwari carded a stage-winning the car down,” he added. Nasser Al Kuwari time of 3hrs 23min 22sec and “The risk paid off because we celebrate after the managed to shave 11min 38sec won the stage today by over 11 final round yesterday. off rival Ahmed Shegawi’s minutes. This is fantastic for us. eventual winning margin of Second place is good with the sit- 45min 53.9sec. uation we had. We could not The performance also earned bring our car. -

Quality of Service Measurements- Mobile Services Network Audit 2012

Quality of Service Measurements- Mobile Services Network Audit 2012 Quality of Service REPORT Mobile Network Audit – Quality of Service – ictQATAR - 2012 The purpose of the study is to evaluate and benchmark Quality Levels offered by Mobile Network Operators, Qtel and Vodafone, in the state of Qatar. The independent study was conducted with an objective End-user perspective by Directique and does not represent any views of ictQATAR. This study is the property of ictQATAR. Any effort to use this Study for any purpose is permitted only upon ictQATAR’s written consent. 2 Mobile Network Audit – Quality of Service – ictQATAR - 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 READER’S ADVICE ........................................................................................ 4 2 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................... 5 2.1 TEAM AND EQUIPMENT ........................................................................................ 5 2.2 VOICE SERVICE QUALITY TESTING ...................................................................... 6 2.3 SMS, MMS AND BBM MEASUREMENTS ............................................................ 14 2.4 DATA SERVICE TESTING ................................................................................... 16 2.5 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS ...................................................................... 23 3 INDUSTRY RESULTS AND INTERNATIONAL BENCHMARK ........................... 25 3.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ -

Qatar-An-Emerging-Sports-Destination

TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE CEO AND BOARD MEMBER 5 KEY HIGHLIGHTS 7 CHAPTER 1: SPORTS IN QATAR 12 CHAPTER 2: SPORTS EVENTS 16 CHAPTER 3: 2022 FIFA WORLD CUP 21 CHAPTER 4: BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES 23 CHAPTER 5: SPORTS ENTITIES 29 CHAPTER 6: SPORTS INFRASTRUCTURE 37 CHAPTER 7: ABOUT THE QFC 42 KEY CONTACTS FOR SETTING UP IN THE QFC 46 APPENDIX 47 GLOSSARY 69 2 QATAR – AN EMERGING SPORTS DESTINATION: BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES 3 MESSAGE FROM THE CEO AND BOARD MEMBER Over the last decade, Qatar has gained an enviable reputation for its ability to hold world-class sporting events to the very highest standards, beginning in 2006 when the nation successfully hosted the Asian Games. In the intervening years, Qatar has grown into a major sporting hub, attracting international events such as the World Indoor Athletics Championships, the Asian Football Confederation Asian Cup, the 24th Men’s Handball World Championship, and the AIBA World Boxing Championship. With ever-more prestigious international events on the horizon, including the 2022 FIFA World Cup and the 2023 FINA World Championships, sport continues to play a pivotal role in and around Qatar, while greatly contributing to the country’s infrastructural development. The sports sector delivers many local and international benefits, which are allowing Qatar to strengthen relations with nations worldwide. And, in an effort to consolidate the country’s commitment to the sporting industry, a Sports Sector Strategy (SSS) was developed as one of the 14-sector strategies within the Qatar National Vision 2030. Given the strategic importance of sports to Qatar’s economy, the Qatar Financial Centre (QFC) developed for the very first time since its establishment this study as an insightful overview into the nation’s sporting ecosystem, highlighting its flourishing business opportunities. -

Al Sadd Look to Stay Unbeaten, Al Rayyan Keen to Nish Third TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK DOHA

QatarTribune Qatar_Tribune No dream start QatarTribuneChannel qatar_tribune for Dustin Johnson at Augusta Masters PAGE 11 FRIDAY, APRIL 9, 2021 Automated offside decisions possible at Qatar World Cup: Wenger DPA/TNN to see if a player was in an 2002 FIFA World Cup Final. tory at the recent FIFA Club FRANKFURT illegal position. Now Collina has another key World Cup. “At the moment, we have role of influence as Chairman “We were happy of the very FIFA official Arsene Wenger situations where the players of FIFA’s Referees Committee, good performance of Edina believes it is realistic an auto- are on lines to see if they are with his position encompassing and her assistant referees, mated system for making off- offside or not,” said Wenger. the development of officials and but we were not surprised,” side calls could be in place by “On average, the time we all aspects of officiating. he said. “All the decisions in the 2022 World Cup in Qatar. have to wait is around 70 sec- “The objective of FIFA is terms of referee selections are “The automated offside I onds, sometimes one minute to have fair results on the field taken because of quality.” think will be ready for 2022,” 20 seconds, sometimes a little of play and technology can Asked about female ref- the 71-year-old Wenger, a for- bit longer when the situation is help achieve this objective,” he erees featuring at the FIFA mer Arsenal manager and now very difficult to appreciate. says. “Part of President Infan- World Cup, Collina said: chief of global football devel- “It is so important because tino’s vision for the future is “We are preparing referees, opment at the world football we see many celebrations are to make VAR more affordable we are not preparing male or governing body, told the Living cancelled after that for marginal for a larger number of member female referees, so the crite- Football Television programme. -

Media Guidelines

MEDIA GUIDELINES Media Guidelines MEDIA FACILITIES ........................................................................................................................2 ACCESS CONTROL ........................................................................................................................2 ACCESS TO SPEAKERS ..................................................................................................................2 PRESS CONFERENCES ..................................................................................................................3 GETTING TO THE VENUES ............................................................................................................3 PHOTOGRAPHY & FILMING .........................................................................................................4 PERSONAL CHECKLIST (IMPORTANT) ...........................................................................................4 TELECOMMUNICATIONS .............................................................................................................5 USEFUL LINKS ..............................................................................................................................5 VISA INFORMATION ....................................................................................................................6 CONGRESS TRANSPORT ...............................................................................................................7 TRANSPORT: OFFICIAL CONGRESS SHUTTLE ............................................................................8 -

CUSTOMER VS PROJECT REFERENCE New.Xlsx

CIKO Projects Reference in Qatar SI No PROJECT DESCRIPTION CONTRACTOR CONSULTANT A Ministery of interior building affair departMent 1NEW POLICE COLLEGE COMPLEX Hassanesco CEG International B Qatar railways CoMpany Qatar Integrated Rail Project 1Redco TCEA Doha metro Red Line North EAG Qatar Integrated Rail Project 2QDVC Al darwish engineering Doha metro RLS UG C aspire zone foundation 1TSE Polishing treatment plant Butec KEO International Consultants 2Al Bayt Stadium at Al Khor City GSIC-JV KEO International Consultants 3Al Bayt stadium Galfar Al Misnad KEO International Consultants 4 Al wakra stadium Smeet Ready mix 5Al Rayyan stadium Larsen and Tubro-Al balagh JV Louis berger D Qatar university Construction of New Students affairs building 1Hassanesco/BOOM KHATIB & ALAMI at Qatar University E al Halul real estate investMent CoMpany 1Doha Oasis Mixed Use Development Redco Al Mana AECOM/DOPMO F asHgHal 1NOH2 QDVC AECOM 2Undergroun car park 7A & 7B in al Bidda Park Bojamhoor KEO International Consultants doha express al muntazah street extension 3Al jaber transport and general contracting Parson project Al dakhira sewage treatment work transfer 4JV Hundai rotem- Aqualia Mace Louis Berger pumping station and associated pipelines 5New Orbital High Way & truck route P023 Leighton contracting AECOM construction of east industrial road between al 6Tekfen construction Parson muntazah and west corridor 7Design & Build of Al Khor Express way Takfen Construction KEO International Consultants 8Al muntazah street extension project Al jaber transport -

Metro Doha – Green Line — World of PORR

World of PORR 165/2014 PORR Projects Metro Doha – Green Line Status update Manfred Lamping Contract award In June 2013, the joint venture PORR-SBG-HBK consisting of Porr Bau GmbH, Saudi Bin Laden Group Riyad and HBK Contracting Company W.L.L. was commissioned with the construction of Green Line M32. The contract was awarded by Qatar Rail. The order volume amounts to 8.989 billion QAR (approx. 1.858 billion Euros as per June 2013). Doha's Metro is an integral part of Qatar's raildevelopment programme. Consisting of four lines, the underground network will cover Doha's metropolitan area and establish connections to the city's central area as well as to various commercial and residential zones located in the city. In Doha's centre, the Metro will run under ground, while it will mostly run at street level or on elevated tracks in the suburban zones. Network Phase 01 2015 Especially for the football world cup in 2022, the Metro will Image: QATAR RAIL 2015 establish connections to the individual stadiums. Execution of construction work Project overview Six tunnel boring machines are operated simultaneously in The Green Line order includes the construction of some 2 x the course of this project. The TBMs were installed in the 2nd 16.5 km of tunnel, six stations and one external switch hall. half of 2014 and started up one after the other until January 2015. Four TMBs started at Al Messila station, two machines Furthermore, four emergency exit shafts up to 40 m deep, 32 eastwards in the direction of the city centre to Musheireb cross-cuts and two additional combined emergency exit/MEP station while the other two started boring westwards towards shafts are being installed. -

Amusement Cities, Parks to Reopen from Sunday

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 MoCI, QNTC urge Qatar’s Nasser private sector to al-Attiyah invest in mega focussed on beach resorts 4th Dakar title published in QATAR since 1978 FRIDAY Vol. XXXXI No. 11780 January 1, 2021 Jumada I 17, 1442 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Last sunset of 2020 Amir, Deputy Amir, Premier exchange New Year greetings Amusement His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani exchanged cables of greetings yesterday with Their Majesties, Highnesses and Excellencies, the leaders of friendly countries, on the occasion of New cities, parks Year, wishing them good health and happiness and their peoples further progress and prosperity. His Highness the Deputy Amir Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad al-Thani also to reopen exchanged cables of greetings with Their Highnesses and Excellencies, crown princes and vice presidents of friendly countries, wishing them good health and happiness and their peoples further progress and from Sunday prosperity. HE the Prime Minister and Minister of Interior Sheikh O MoCI stipulates 50% capacity, for now Khalid bin Khalifa bin Abdulaziz al-Thani also exchanged cables of By Joey Aguilar z Visitors are allowed entry only af- greetings with Their Excellencies, Staff Reporter ter checking their health status code in heads of government of friendly the Ehteraz app, and only those with a The last sunset of 2020 from the vicinity of one of Qatar’s globally acclaimed tourist attractions, The Museum of Islamic countries, wishing them health and green code are allowed entry, with the Art in Doha. PICTURE: Thajudheen wellness and their peoples further musement cities and parks exception of children. -

Family & Casual

FAMILY & CASUAL ACTIVATE Y UR MEMBERSHIP Enjoy even more Entertainer Offers on your phone! Outlet Name Location Cuisine Code T.G.I Friday's Bin, Omran, The Pearl International D01 Aalishan Al Muntazah Indian D02 Al Matbakh Arumalia Boutique Hotel International D03 Al Tabkha Porto Arabia Lebanese D04 Argan Al Jasra Boutique Hotel Moroccan D05 Belgian Cafe InterContinental Doha Belgian D06 Biella Multiple Locations Italian D07 Biriyani Hut Al Wakra Indian D08 Bread and Bagels West Bay International D09 Burger Gourmet Lagoona Mall International D10 Butcher Shop & Grill Vilaggio Mall Steakhouse D11 California Tortilla Multiple Locations Mexican D12 Carluccio's Porto Arabia Italian D13 Casa Paco The Pearl Spanish D14 Casper & Gambini's Landmark Mall International D15 Choices Copthorne Hotel Doha International D16 Coral All Day Dining InterContinental Doha International D17 Cosmo Millennium Hotel Doha International D18 Crepaway Ezdan Mall, Muthana Complex International D19 Crossroads Kitchen Marriott Marquis City Centre Doha International D20 Cucina Marriott Marquis City CentreDoha Italian D21 Dunia Villaggio Mall Arabic D22 Eli France Café Multiple Locations International D23 Gerry's Grill Opposite Family Food Centre Asian D24 La Brasserie Mercure Grand Hotel Doha International D25 © The Entertainer FZ-LLC 2015 TE Qatar Ind Final 2015.indd 8 11/26/14 5:20 PM Family & Casual | Index | Outlet Name Location Cuisine Code La Piazza Al Bidda Boutique Hotel Italian D26 Lagoon Ristorante Sealine Beach Resort Italian D27 Le Bouquet Lexington Gloria