The First Century of Right to Arms Litigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 of 56 in the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for THE

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA CITY OF PHILADELPHIA, : GUARDIAN CIVIC LEAGUE OF : CIVIL ACTION NO. PHILADELPHIA, ASPIRA, INC. OF : PENNSYLVANIA, RESIDENTS : 2000-CV-2463 ADVISORY BOARD, NORTHEAST : HOME SCHOOL AND BOARD, and : PHILADELPHIA CITIZENS FOR : CHILDREN AND YOUTH, : : Plaintiffs; : : v. : : BERETTA U.S.A., CORP., : BROWNING, INC., BRYCO ARMS, : INC., COLT’S MANUFACTURING : CO., GLOCK, INC., HARRINGTON & : RICHARDSON, INC., : INTERNATIONAL ARMAMENT : INDUSTRIES, INC., KEL-TEC, CNC, : LORCIN ENGINEERING CO., : NAVEGAR, INC., PHOENIX/RAVEN : ARMS, SMITH & WESSON CORP., : STURM, RUGER & CO., and TAURUS : INTERNATIONAL FIREARMS, : ET AL., : : Defendants. : O P I N I O N Date: December 20, 2000 Schiller, J. Page 1 of 56 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................. 3 STANDARD FOR MOTION TO DISMISS ......................................... 4 REGULATION OF FIREARMS .................................................. 5 FACTS ALLEGED IN THE COMPLAINT ......................................... 6 DISCUSSION ................................................................ 8 I. Philadelphia’s suit is barred by the Uniform Firearms Act (“UFA”) .......... 8 A. Section 6120 ................................................ 8 B. Section 6120(a.1) (“UFA Amendment”) ......................... 10 1. Plain meaning ........................................ 10 2. Impetus for statute .................................... 11 3. Legislative history ................................... -

PICS Denial Challenge Form

SP 4-197 (9-2016) PENNSYLVANIA STATE POLICE PENNSYLVANIA INSTANT CHECK SYSTEM CHALLENGE Any challenge to a decision made by the Pennsylvania Instant Check System (PICS) concerning a background check must be completed and submitted by mail (faxed copies will not be accepted), within 30 days from the date of denial to the Pennsylvania State Police, Firearms Division, PICS Challenge Section, 1800 Elmerton Avenue, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17110. Only background checks processed through PICS that were NOT approved will be processed by the Pennsylvania State Police, PICS Challenge Section. Please type or print clearly with blue or black ink. ALL CHALLENGES SUBMITTED MUST BE LEGIBLE AND SIGNED AND DATED ON PAGE 4 BY THE APPLICANT OR THEY WILL BE RETURNED. The Pennsylvania State Police will respond in writing within 5 business days of receipt of this form. You are encouraged to provide additional information for the purpose of review, such as information you may have regarding dispositions on old arrest records, etc., that may be helpful in expediting the processing of your file. Be advised that within 60 days of receipt of a valid challenge, a final decision will be provided to you by this Office. You may also file a separate appeal with the FBI, NICS Section. PART I: REASON FOR CHALLENGE REQUEST- Check the appropriate box that indicates the type of background check: Purchase/Transfer License to Carry Firearm Return RLEIA/LEOSA PART II: DATE AND LOCATION OF BACKGROUND CHECK Date of background check: Location of Firearm Dealer/County Sheriff/Police -

Information for Pennsylvania Firearm Purchasers and Basic Firearm Safety

§ 3502 Burglary 4. has been adjudicated as an incompetent or who has person is eligible to purchase a firearm or acquire a SP 4-135 (10-2008) § 3503 Criminal trespass, if a felony of the been involuntarily committed to a mental institution license to carry a firearm. second degree or higher for treatment under § 302, 303, or 304 under the § 3701 Robbery Mental Health Procedures Act (P.L. 817, No. 143); or Pennsylvania Firearm Dealers and County Sheriffs INFORMATION FOR 5. is an alien, is illegally or unlawfully in the United access the PICS program through a toll free telephone § 3702 Robbery of motor vehicle States; or number. Operation has shown that approximately 91% PENNSYLVANIA § 3921 Theft by unlawful taking or disposition, 6. is the subject of an active protection from abuse of the individuals attempting to purchase a firearm can FIREARM PURCHASERS upon conviction of the second felony order issued pursuant to 23 Pa.C.S. § 6108, relating be approved while on the initial call. offense to relief, which order provides for the relinquishment § 3923 Theft by extortion, when the offense is of firearms; or By law, no record information may be disseminated as & accompanied by threats of violence 7. was adjudicated delinquent (with conditions specified a result of the background check. At times, temporary § 3925 Receiving stolen property, upon in the UFA). With the exception of crimes committed delays may be necessary. If a record is identified and BASIC under sections 2502, 2503, 2702, 2703, 2704, 2901, is incomplete, it is necessary to research the record and conviction of the second felony offense FIREARM SAFETY §4906 False reports to law enforcement 3121, 3123, 3301, 3502, 3701, and 3923, this contact the agency(s) that may be able to provide prohibition may terminate 15 years after the last information required in order to complete the authorities, if the fictitious report applicable delinquent adjudication or upon the background check. -

The General Assembly

1508 THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY final reason for the proposed revisions is that the Com- Title 204—JUDICIAL mission seeks to clarify several issues raised by the appellate courts and relating to the sentencing guidelines, SYSTEM GENERAL such as the definition of school zone for purposes of the Youth/School Enhancement and the use of a previous PROVISIONS court-martial in the Prior Record Score calculation. PART VIII. COMMISSION ON SENTENCING Revisions to Section 303.1—Sentencing guidelines stan- dards [204 PA. CODE CH. 303] The standards contained in this section identify of- Adoption of Sentencing Guidelines fenses for which courts must consider the sentencing guidelines, and offenses to which the guidelines do not The Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing is hereby apply; describe the application of the various editions of submitting revised sentencing guidelines, 204 Pa. Code the guidelines; and describe the requirements for report- §§ 303.1—303.18, for consideration by the General As- ing sentences to the Commission. sembly. The Commission adopted the revised sentencing guidelines on August 11, 2004, published them for com- The Commission included in previous Sentencing ment at 34 Pa.B. 5746 (October 23, 2004), and held public Guidelines Implementation Manuals commentary regard- hearings on December 1, 2004, December 2, 2004, Decem- ing the merger of sentences, advising courts that the ber 9, 2004 and December 14, 2004. The Commission guidelines do not apply to convictions for lesser offenses modified the proposed guidelines on December 15, 2004, which merge for sentencing purposes into greater of- published them for comment at 35 Pa.B. 198 (January 8, fenses. -

Glossary of Terms and Criminal Codes

Glossary of Terms and Criminal Codes QUICK SEARCH: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVW A A Assault A ARMED Assault, armed A INT MAIM Assault with intent to maim A TO K (or MAIM, MUR, Assault to kill (or maim, murder, rape, rob…) RAPE, ROB…) A & B Assault and Battery AA/DW Aggravated Assault with a deadly weapon AA/PO Aggravated Assault police officer AA/SBI Aggravated Assault/serious bodily injury AAWW Aggravated Assault with weapon ABC Act Alcoholic Beverage Control Act ABD Abduction ABNDN or ABNDNT Abandon or Abandonment ABST Abstraction ABUS LANG Abusive language ABWIK Assault and Battery with intent to kill ACAF Accessory after the fact ACBF Accessory before the fact ACC Accessory ACC BURG Accessory to burglary ACC TO ISS CHK Accessory to issuing check ACC TO JL BRK Accessory to jail break ACC TO L Accessory to larceny ACC TO MUR Accessory to murder ACC TO ROB Accessory to robbery ACCOP DD Accompanying drunken driver ACCPL Accomplice ACCPT BRB Accepting a bribe ADJ Adjudication ADLTY Adultery ADW Assault with deadly weapon ADW/FIREARM Assault with deadly weapon/firearms AFA Alien Firearms Act A Z AFDVT Affidavit (written statement of facts voluntarily made by an affiant under an oath or affirmation administered by a person authorized to do so by law) AFFR WDW Affray (fighting in public place that disturbs peace) with deadly weapon AFO Assaulting a federal officer AGG A Aggravated Assault AID & ABET LOTT Aiding and abetting lottery AID & HAR ESC PR Aiding and harboring an escaped prisoner AID PR TO ESC Aiding a prisoner to escape AIDA Automobile Information Disclosure Act AKA Also known as ALIEN POSS FIREARMS Alien in possession of firearms ALLOW DR W/O PRMT Allowing one to drive without a permit ALT Altering ANNOY & SOL Annoying and soliciting APC Actual physical control APCV Actual physical control of a vehicle APIPOCC Appropriating property in possession of common carrier APP. -

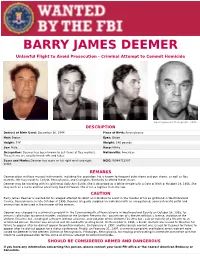

BARRY JAMES DEEMER Unlawful Flight to Avoid Prosecution - Criminal Attempt to Commit Homicide

BARRY JAMES DEEMER Unlawful Flight to Avoid Prosecution - Criminal Attempt to Commit Homicide Age Progressed Photograph - 2014 DESCRIPTION Date(s) of Birth Used: December 16, 1944 Place of Birth: Pennsylvania Hair: Brown Eyes: Green Height: 5'9" Weight: 240 pounds Sex: Male Race: White Occupation: Deemer has been known to sell items at flea markets. Nationality: American These items are usually knock-offs and fakes. Scars and Marks: Deemer has scars on his right wrist and right NCIC: W984713307 ankle. REMARKS Deemer plays multiple musical instruments, including the accordion. He is known to frequent auto shows and gun shows, as well as flea markets. He may travel to Carlyle, Pennsylvania, and Covington, Kentucky to attend these shows. Deemer may be traveling with his girlfriend, Sally Ann Suttle. She is described as a White female with a Date of Birth of October 29, 1956. She may work as a nurse and has previously lived in Hawaii. She is not a fugitive from the law. CAUTION Barry James Deemer is wanted for his alleged attempt to solicit an individual to assist in the murder of his ex-girlfriend in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, in late October of 1995. Deemer allegedly supplied an individual with an unregistered, semi-automatic pistol and ammunition to be used in the murder of the woman. Deemer was charged via a criminal complaint in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in Westmoreland County on October 24, 1995, for criminal solicitation to commit murder, violation of the Uniform Firearms Act - possession of a firearm without a license, violation of the Uniform Firearms Act - lending of a firearm without a license, and violation of the Uniform Firearms Act - sale or transfer of a firearm to an unlicensed person. -

Firearms Removal/Retrieval in Cases of Domestic Violence

1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................ 5 NOTES ON THE TEXT ..................................................................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 14 SCOPE OF THE REPORT ................................................................................................................. 14 DOMESTIC VIOLENCE HOMICIDE DATA............................................................................................. 14 Chart 1 ................................................................................................................................... 15 WHY THIS REPORT IS NECESSARY .................................................................................................. 16 AUTHORITY FOR REMOVAL/RETRIEVAL .................................................................................. 17 CIVIL PROTECTIVE ORDERS ........................................................................................................... 17 Explicit Authority ...................................................................................................................... 17 Figure 1 ................................................................................................................................. -

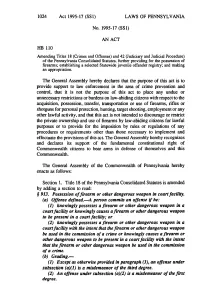

The General Assembly Hereby Declares That the Purpose of This Act Is to Provide Support to Law Enforcement in the Area of Crime

1024 Act 1995-17 (SSI) LAWS OF PENNSYLVANIA No. 1995-17 (SS1) AN ACT HB 110 Amending Titles 18 (Crimes and Offenses) and 42 (Judiciary and Judicial Procedure) of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes, further providing for the possessionof firearms; establishing a selected Statewide juvenile offender registry; and making an appropriation. The General Assembly hereby declares that the purpose of this act is to provide support to law enforcement in the area of crime prevention and control, that it is not the purpose of this act to place any undue or unnecessary restrictions or burdens on law-abiding citizens with:respectlo:the acquisition, possession, transfer, transportation or use of firearms, rifles or shotguns for personal protection, hunting, target shooting, employment or any other lawful activity, and that this actis not intended to discourage or restrict the private ownership and use of firearms by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes or to provide for the imposition by rules or regulations of any procedures or requirements other than those necessary to implement and effectuate the provisionsof thisact. The General Assembly herebyrecognizes and declares its support of the fundamental constitutional right of Commonwealth citizens to bear anus in defense of themselves and this Commonwealth. The General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania hereby enacts as follows: Section 1. Title 18 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes is amended by adding a section to read: § 913. Possession offirearm or other dangerous weapon in -

Title 204. Judicial System General Provisions Part VIII Criminal Sentencing Chapter 303

Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing Title 204. Judicial System General Provisions Part VIII Criminal Sentencing Chapter 303. Sentencing Guidelines §303.1. Sentencing guidelines standards. (a) The court shall consider the sentencing guidelines in determining the appropriate sentence for offenders convicted of, or pleading guilty or nolo contendere to, felonies and misdemeanors. Where crimes merge for sentencing purposes, the court shall consider the sentencing guidelines only on the offense assigned the higher offense Gravity score. (b) The sentencing guidelines do not apply to sentences imposed as a result of the following: accelerated rehabilitative disposition; disposition in lieu of trial; direct or indirect contempt of court; violations of protection from abuse orders; revocation of probation, intermediate punishment or parole. (c) The sentencing guidelines shall apply to all offenses committed on or after the effective date of the guidelines. Amendments to the guidelines shall apply to all offenses committed on or after the date the amendment becomes part of the guidelines. (1) When there are current multiple convictions for offenses that overlap two sets of guidelines, the former guidelines shall apply to offenses that occur prior to the effective date of the amendment and the later guidelines shall apply to offenses that occur on or after the effective date of the amendment. If the specific dates of the offenses cannot be determined, then the later guidelines shall apply to all offenses. (2) The initial sentencing guidelines went into effect on July 22, 1982 and applied to all crimes committed on or after that date. Amendments to the guidelines went into effect in June 1983, January 1986 and June 1986. -

Table of Contents Title 18 Crimes and Offenses Part I

TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE 18 CRIMES AND OFFENSES PART I. PRELIMINARY PROVISIONS Chapter 1. General Provisions § 101. Short title of title. § 102. Territorial applicability. § 103. Definitions. § 104. Purposes. § 105. Principles of construction. § 106. Classes of offenses. § 107. Application of preliminary provisions. § 108. Time limitations. § 109. When prosecution barred by former prosecution for the same offense. § 110. When prosecution barred by former prosecution for different offense. § 111. When prosecution barred by former prosecution in another jurisdiction. § 112. Former prosecution before court lacking jurisdiction or when fraudulently procured by the defendant. Chapter 3. Culpability § 301. Requirement of voluntary act. § 302. General requirements of culpability. § 303. Causal relationship between conduct and result. § 304. Ignorance or mistake. § 305. Limitations on scope of culpability requirements. § 306. Liability for conduct of another; complicity. § 307. Liability of organizations and certain related persons. § 308. Intoxication or drugged condition. § 309. Duress. § 310. Military orders. § 311. Consent. § 312. De minimis infractions. § 313. Entrapment. § 314. Guilty but mentally ill. § 315. Insanity. Chapter 5. General Principles of Justification § 501. Definitions. § 502. Justification a defense. § 503. Justification generally. § 504. Execution of public duty. § 505. Use of force in self-protection. § 506. Use of force for the protection of other persons. § 507. Use of force for the protection of property. § 508. Use of force in law enforcement. § 509. Use of force by persons with special responsibility for care, discipline or safety of others. § 510. Justification in property crimes. Chapter 7. Responsibility (Reserved) Chapter 9. Inchoate Crimes § 901. Criminal attempt. § 902. Criminal solicitation. § 903. Criminal conspiracy. § 904. Incapacity, irresponsibility or immunity of party to solicitation or conspiracy. -

J-E04004-17 2020 PA Super 107 COMMONWEALTH OF

J-E04004-17 2020 PA Super 107 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA : IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF : PENNSYLVANIA Appellee : : v. : : EMILY JOY GROSS : : Appellant : No. 375 EDA 2016 Appeal from the Order January 15, 2016 In the Court of Common Pleas of Monroe County Criminal Division at No(s): CP-45-CR-0000045-2010 BEFORE: GANTMAN, P.J., BENDER, P.J.E., BOWES, J., PANELLA, J., SHOGAN, J., LAZARUS, J., OLSON, J., STABILE, J., and DUBOW, J. OPINION BY GANTMAN, P.J.: FILED APRIL 29, 2020 Appellant, Emily Joy Gross, appeals from the order entered in the Monroe County Court of Common Pleas, which denied her omnibus pretrial motion to dismiss on double jeopardy grounds. We affirm. Our Supreme Court set forth the relevant facts of this case as follows: [Ms.] Gross and Daniel Autenrieth began a romantic relationship in early 2009. On May 4, 2009, Autenrieth’s estranged wife filed a protection from abuse (PFA) petition against him in Northampton County where she lived. The court issued a temporary PFA order the same day prohibiting Autenrieth from having contact with his wife or children and evicting him from the marital residence. The same day, deputies from the Northampton Sheriff’s office went to Autenrieth’s residence (also in Northampton County) to serve the temporary PFA order and to transfer custody of the children to Autenrieth’s wife. [Ms.] Gross was present, babysitting the children, and a deputy served the order on her as the adult in charge of the residence. The deputy incorrectly told [Ms.] Gross the temporary PFA order prohibited Autenrieth from possessing firearms. -

Uniform Pistol Act Sam B

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 29 Article 4 Issue 4 November-December Winter 1938 Uniform Pistol Act Sam B. Warner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Sam B. Warner, Uniform Pistol Act, 29 Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 529 (1938-1939) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE UNIFORM PISTOL ACT* SAM B. Wiuamt Restrictions on the use of pistols are nothing new. The first state to pass a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed pistols was Kentucky in 1813.1 Though Indiana followed in 18202 and Arkansas and Georgia in 1837, 3 such statutes did not become com- mon4 until after the passage of the New York Sullivan Law in 1911.5 *I am indebted to Mrs. Marion -D. Frankfurter for reading the manuscript and making many valuable suggestions and to Mr. Robert Greenfield for assis- tance on the notes. 1 Ky. Acts 1812-13, c. 89 prohibits carrying concealed pistols except when travelling. Declared unconstitutional in Bliss v. Commonwealth, 2 Litt. 90 (1822). Constitution was amended in 1850 to permit prohibitions on carrying concealed weapons. See Ky. Constitution of 1850, art. 13, §25. An act to prohibit the carry- ing of concealed weapons was passed in 1854.