Uniform Pistol Act Sam B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Legal to Lethal: Converted Firearms in Europe

Small Arms Survey Maison de la Paix Report Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E April 1202 Geneva 2018 Switzerland t +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 e [email protected] About the Lethal to Legal From Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is a global centre of excellence whose mandate is to generate impar- tial, evidence-based, and policy-relevant knowledge on all aspects of small arms and armed FROM LEGAL TO LETHAL violence. It is the principal international source of expertise, information, and analysis on small arms and armed violence issues, and acts as a resource for governments, policy- makers, researchers, and civil society. It is located in Geneva, Switzerland, at the Graduate Converted Firearms in Europe Institute of International and Development Studies. The Survey has an international staff with expertise in security studies, political science, Nicolas Florquin and Benjamin King law, economics, development studies, sociology, and criminology, and collaborates with a network of researchers, partner institutions, non-governmental organizations, and govern- ments in more than 50 countries. For more information, please visit: www.smallarmssurvey.org. A publication of the Small Arms Survey with support the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs and the German Federal Foreign Office FROM LEGAL TO LETHAL Converted Firearms in Europe Nicolas Florquin and Benjamin King A publication of the Small Arms Survey with support from the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs and the German Federal Foreign Office. Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, 2018 First published in April 2018 All rights reserved. -

Page 1 of 56 in the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for THE

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA CITY OF PHILADELPHIA, : GUARDIAN CIVIC LEAGUE OF : CIVIL ACTION NO. PHILADELPHIA, ASPIRA, INC. OF : PENNSYLVANIA, RESIDENTS : 2000-CV-2463 ADVISORY BOARD, NORTHEAST : HOME SCHOOL AND BOARD, and : PHILADELPHIA CITIZENS FOR : CHILDREN AND YOUTH, : : Plaintiffs; : : v. : : BERETTA U.S.A., CORP., : BROWNING, INC., BRYCO ARMS, : INC., COLT’S MANUFACTURING : CO., GLOCK, INC., HARRINGTON & : RICHARDSON, INC., : INTERNATIONAL ARMAMENT : INDUSTRIES, INC., KEL-TEC, CNC, : LORCIN ENGINEERING CO., : NAVEGAR, INC., PHOENIX/RAVEN : ARMS, SMITH & WESSON CORP., : STURM, RUGER & CO., and TAURUS : INTERNATIONAL FIREARMS, : ET AL., : : Defendants. : O P I N I O N Date: December 20, 2000 Schiller, J. Page 1 of 56 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................. 3 STANDARD FOR MOTION TO DISMISS ......................................... 4 REGULATION OF FIREARMS .................................................. 5 FACTS ALLEGED IN THE COMPLAINT ......................................... 6 DISCUSSION ................................................................ 8 I. Philadelphia’s suit is barred by the Uniform Firearms Act (“UFA”) .......... 8 A. Section 6120 ................................................ 8 B. Section 6120(a.1) (“UFA Amendment”) ......................... 10 1. Plain meaning ........................................ 10 2. Impetus for statute .................................... 11 3. Legislative history ................................... -

PICS Denial Challenge Form

SP 4-197 (9-2016) PENNSYLVANIA STATE POLICE PENNSYLVANIA INSTANT CHECK SYSTEM CHALLENGE Any challenge to a decision made by the Pennsylvania Instant Check System (PICS) concerning a background check must be completed and submitted by mail (faxed copies will not be accepted), within 30 days from the date of denial to the Pennsylvania State Police, Firearms Division, PICS Challenge Section, 1800 Elmerton Avenue, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17110. Only background checks processed through PICS that were NOT approved will be processed by the Pennsylvania State Police, PICS Challenge Section. Please type or print clearly with blue or black ink. ALL CHALLENGES SUBMITTED MUST BE LEGIBLE AND SIGNED AND DATED ON PAGE 4 BY THE APPLICANT OR THEY WILL BE RETURNED. The Pennsylvania State Police will respond in writing within 5 business days of receipt of this form. You are encouraged to provide additional information for the purpose of review, such as information you may have regarding dispositions on old arrest records, etc., that may be helpful in expediting the processing of your file. Be advised that within 60 days of receipt of a valid challenge, a final decision will be provided to you by this Office. You may also file a separate appeal with the FBI, NICS Section. PART I: REASON FOR CHALLENGE REQUEST- Check the appropriate box that indicates the type of background check: Purchase/Transfer License to Carry Firearm Return RLEIA/LEOSA PART II: DATE AND LOCATION OF BACKGROUND CHECK Date of background check: Location of Firearm Dealer/County Sheriff/Police -

Manual Pistola Jericho 941

Manual Pistola Jericho 941 Jericho 941/ quick cleaning w/ PB Blaster. adamsbranch2011 Desert Eagle Video Operation. I've owned both but the Jericho 941 is my favorite of the two although the BHP has more boxes and manuals, the Desert Eagle even comes with three magazines. La Jericho 941 / Baby Desert Eagle (en Estados Unidos) es una pistola de. vs Israel Weapon Industries Jericho 941 F/R 9mm Luger Pistol. Add to Comparison Accessory Rail, Backstraps, Cleaning Brush/Kit, Manual, Speed Loader. –. Valsts Policijas klasificÄ“to Ä«sstobra vÄ«tņstobra Å¡aujamieroÄ u. The Israel Weapon Industries Jericho 941 FS/RS is a Semi-Automatic pistol that shoots 9mm Luger ammunition. With a maximum capacity of 16 rounds,. Manual Pistola Jericho 941 Read/Download Shorty USA - Cybergun/KWC IWI Jericho 941 Gen 2 CO2 Softair Pistol. Add to EJ Playlist - Very good condition - as new condition with boxes and manuals. I recently picked up a Disparo con Pistola Jericho 941 CO2. Add to EJ Playlist. + 2000 bolinhas 05:05. Review pistola de balines vs Nerf &, Aire comprimido 12:36 Cybergun - KWC IWI Jericho 941 Metal Slide CO2 BB Gun Review 15:10. Airsoft homemade amazing airgun 08:32. Airgun caseira manual 02:31. Arms 941 CO2 Pistol. Air guns. * Swiss Arms 941 CO2 pistol * Uses a 12-gram CO2 cartridge * 22rd BB magazine * Semiauto * Fixed front and rear sights. Pistola Full Metal Glock KWC Blowback Manual BB 6 mm Spring Cybergun - KWC IWI Jericho 941 Metal Slide CO2 BB Gun Review They All Should Read A Photoshop Manual Before Doing Such This gallery will make you Pistola Jericho 941co2 Full Metal Modelo 2013full Accesorios. -

Information for Pennsylvania Firearm Purchasers and Basic Firearm Safety

§ 3502 Burglary 4. has been adjudicated as an incompetent or who has person is eligible to purchase a firearm or acquire a SP 4-135 (10-2008) § 3503 Criminal trespass, if a felony of the been involuntarily committed to a mental institution license to carry a firearm. second degree or higher for treatment under § 302, 303, or 304 under the § 3701 Robbery Mental Health Procedures Act (P.L. 817, No. 143); or Pennsylvania Firearm Dealers and County Sheriffs INFORMATION FOR 5. is an alien, is illegally or unlawfully in the United access the PICS program through a toll free telephone § 3702 Robbery of motor vehicle States; or number. Operation has shown that approximately 91% PENNSYLVANIA § 3921 Theft by unlawful taking or disposition, 6. is the subject of an active protection from abuse of the individuals attempting to purchase a firearm can FIREARM PURCHASERS upon conviction of the second felony order issued pursuant to 23 Pa.C.S. § 6108, relating be approved while on the initial call. offense to relief, which order provides for the relinquishment § 3923 Theft by extortion, when the offense is of firearms; or By law, no record information may be disseminated as & accompanied by threats of violence 7. was adjudicated delinquent (with conditions specified a result of the background check. At times, temporary § 3925 Receiving stolen property, upon in the UFA). With the exception of crimes committed delays may be necessary. If a record is identified and BASIC under sections 2502, 2503, 2702, 2703, 2704, 2901, is incomplete, it is necessary to research the record and conviction of the second felony offense FIREARM SAFETY §4906 False reports to law enforcement 3121, 3123, 3301, 3502, 3701, and 3923, this contact the agency(s) that may be able to provide prohibition may terminate 15 years after the last information required in order to complete the authorities, if the fictitious report applicable delinquent adjudication or upon the background check. -

The General Assembly

1508 THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY final reason for the proposed revisions is that the Com- Title 204—JUDICIAL mission seeks to clarify several issues raised by the appellate courts and relating to the sentencing guidelines, SYSTEM GENERAL such as the definition of school zone for purposes of the Youth/School Enhancement and the use of a previous PROVISIONS court-martial in the Prior Record Score calculation. PART VIII. COMMISSION ON SENTENCING Revisions to Section 303.1—Sentencing guidelines stan- dards [204 PA. CODE CH. 303] The standards contained in this section identify of- Adoption of Sentencing Guidelines fenses for which courts must consider the sentencing guidelines, and offenses to which the guidelines do not The Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing is hereby apply; describe the application of the various editions of submitting revised sentencing guidelines, 204 Pa. Code the guidelines; and describe the requirements for report- §§ 303.1—303.18, for consideration by the General As- ing sentences to the Commission. sembly. The Commission adopted the revised sentencing guidelines on August 11, 2004, published them for com- The Commission included in previous Sentencing ment at 34 Pa.B. 5746 (October 23, 2004), and held public Guidelines Implementation Manuals commentary regard- hearings on December 1, 2004, December 2, 2004, Decem- ing the merger of sentences, advising courts that the ber 9, 2004 and December 14, 2004. The Commission guidelines do not apply to convictions for lesser offenses modified the proposed guidelines on December 15, 2004, which merge for sentencing purposes into greater of- published them for comment at 35 Pa.B. 198 (January 8, fenses. -

Glossary of Terms and Criminal Codes

Glossary of Terms and Criminal Codes QUICK SEARCH: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVW A A Assault A ARMED Assault, armed A INT MAIM Assault with intent to maim A TO K (or MAIM, MUR, Assault to kill (or maim, murder, rape, rob…) RAPE, ROB…) A & B Assault and Battery AA/DW Aggravated Assault with a deadly weapon AA/PO Aggravated Assault police officer AA/SBI Aggravated Assault/serious bodily injury AAWW Aggravated Assault with weapon ABC Act Alcoholic Beverage Control Act ABD Abduction ABNDN or ABNDNT Abandon or Abandonment ABST Abstraction ABUS LANG Abusive language ABWIK Assault and Battery with intent to kill ACAF Accessory after the fact ACBF Accessory before the fact ACC Accessory ACC BURG Accessory to burglary ACC TO ISS CHK Accessory to issuing check ACC TO JL BRK Accessory to jail break ACC TO L Accessory to larceny ACC TO MUR Accessory to murder ACC TO ROB Accessory to robbery ACCOP DD Accompanying drunken driver ACCPL Accomplice ACCPT BRB Accepting a bribe ADJ Adjudication ADLTY Adultery ADW Assault with deadly weapon ADW/FIREARM Assault with deadly weapon/firearms AFA Alien Firearms Act A Z AFDVT Affidavit (written statement of facts voluntarily made by an affiant under an oath or affirmation administered by a person authorized to do so by law) AFFR WDW Affray (fighting in public place that disturbs peace) with deadly weapon AFO Assaulting a federal officer AGG A Aggravated Assault AID & ABET LOTT Aiding and abetting lottery AID & HAR ESC PR Aiding and harboring an escaped prisoner AID PR TO ESC Aiding a prisoner to escape AIDA Automobile Information Disclosure Act AKA Also known as ALIEN POSS FIREARMS Alien in possession of firearms ALLOW DR W/O PRMT Allowing one to drive without a permit ALT Altering ANNOY & SOL Annoying and soliciting APC Actual physical control APCV Actual physical control of a vehicle APIPOCC Appropriating property in possession of common carrier APP. -

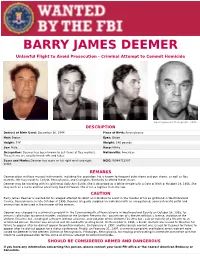

BARRY JAMES DEEMER Unlawful Flight to Avoid Prosecution - Criminal Attempt to Commit Homicide

BARRY JAMES DEEMER Unlawful Flight to Avoid Prosecution - Criminal Attempt to Commit Homicide Age Progressed Photograph - 2014 DESCRIPTION Date(s) of Birth Used: December 16, 1944 Place of Birth: Pennsylvania Hair: Brown Eyes: Green Height: 5'9" Weight: 240 pounds Sex: Male Race: White Occupation: Deemer has been known to sell items at flea markets. Nationality: American These items are usually knock-offs and fakes. Scars and Marks: Deemer has scars on his right wrist and right NCIC: W984713307 ankle. REMARKS Deemer plays multiple musical instruments, including the accordion. He is known to frequent auto shows and gun shows, as well as flea markets. He may travel to Carlyle, Pennsylvania, and Covington, Kentucky to attend these shows. Deemer may be traveling with his girlfriend, Sally Ann Suttle. She is described as a White female with a Date of Birth of October 29, 1956. She may work as a nurse and has previously lived in Hawaii. She is not a fugitive from the law. CAUTION Barry James Deemer is wanted for his alleged attempt to solicit an individual to assist in the murder of his ex-girlfriend in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, in late October of 1995. Deemer allegedly supplied an individual with an unregistered, semi-automatic pistol and ammunition to be used in the murder of the woman. Deemer was charged via a criminal complaint in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in Westmoreland County on October 24, 1995, for criminal solicitation to commit murder, violation of the Uniform Firearms Act - possession of a firearm without a license, violation of the Uniform Firearms Act - lending of a firearm without a license, and violation of the Uniform Firearms Act - sale or transfer of a firearm to an unlicensed person. -

This Is NOT the Current IDPA Rule Book. This Is the Version That Was

NOTE: This is NOT the current IDPA rule book. This is the version that was originally printed with a green cover (i.e., the “Little Green Book”). It was replaced by the 2005 revision. Always check the IDPA website for the latest rules. 2232 CR 719 Berryville, AR 72616 Phone: 870-545-3886 Fax: 870-545-3894 E-mail: [email protected] Equipment and Competition Rules of the International Defensive Pistol Association, Inc., adopted 10/26/96, updated 05-02-01. Copyright © 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001 International Defensive Pistol Association, Inc., all rights reserved. Following are the official rules governing "Defensive Pistol" Competition as a shooting discipline. THE CONDUCT OF DEFENSIVE PISTOL COMPETITION Purpose: Defensive Pistol shooting as a sport is quite simply the use of practical equipment including full charge service ammunition to solve simulated "real world" self-defense scenarios. Shooters competing in Defensive Pistol events are required to use practical handguns and holsters that are truly suitable for self-defense use. No "competition only" equipment is permitted in Defensive Pistol matches since the main goal is to test the skill and ability of the individual, not their equipment or gamesmanship. Principles: •To create a level playing field for all competitors to test the skill and ability of the individual, not their equipment or gamesmanship. 1 •To promote safe and proficient use of guns and equipment suitable for self- defense use. •To offer a competition forum for shooters using standard factory produced service pistols such as the Beretta 92F, Glock 17, etc. (STOCK SERVICE PISTOL Division); for shooters using popular single action 9mm/.40 pistols which have been modified for carry (ENHANCED SERVICE PISTOL Division); for shooters using 1911 style single stack .45's which have been modified for carry, not competition (CUSTOM DEFENSIVE PISTOL Division); and for shooters using service revolvers such as the popular Smith & Wesson 686 (STOCK SERVICE REVOLVER Division). -

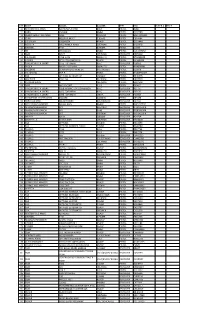

NEW GUN LIST OCT12.Xlsx

LOT MAKE MODEL CALIBER TYPE SN# BUYER # PRICE 10 MASTERPIECE ARMS MPA22SST-A MINI 22LR PISTOL J5821 11 PARA CSX 89R 9MM PISTOL P237289 12 HENRY REPEATING ARMS H001 22S/L/LR PISTOL HM11000402 13 IO INC HELLPUP AK-47 7.62x49 PISTOL *014484 14 SIG SAUER 191145STX 45ACP PISTOL GS27448 15 ROSSI FA RH92 RANCH HAND .357MAG PISTOL K285978 16 GRENDEL P-30 22WMR PISTOL 11948 17 HK PIP2000-V2 9MM PISTOL 116-039152 18 S&W M627 .357MAG REVOLVER CPZ5919 19 SIG SAUER P238 HDW 380AUTO PISTOL 27A058838 20 KIMBER STS ULTRA RAPTOR II 45ACP PISTOL KU149498 21 TAYLOR'S&CO A UBERTI 1875 TOP BREAK 45LC REVOLVER F06809 22 RUGER M03712 LCP-NRA 380AUTO PISTOL NRA000681 23 LASSERRE SUMPER COMANCHE SA 45LC/410GA PISTOL 219346 24 FN HERSTAL FNP-9 9MM PISTOL 61BMP12407 25 EAA WITNESS ELITE MATCH .40S&W PISTOL EA49745 26 WALTHER P99C QA 9X19MM PISTOL FAH7026 27 COONAN ARMS B .357MAG PISTOL B004598 28 S&W M61 ESCORT 22LR PISTOL B60427 29 TAYLOR'S&CO A UBERTI 1858 REMINGTON CONVERSON 45LC REVOLVER X22757 30 TAYLOR'S&CO A UBERTI 1875 TOP BREAK 45LC REVOLVER F07635 31 TAYLOR'S&CO A UBERTI 1875 TOP BREAK .38SPL REVOLVER F05809 32 THOMPSON CENTER ARMS ENCORE 500S&W PISTOL 583688 33 HERITAGE MFG ROUGH RIDER 22LR/22MAG REVOLVER E17917 34 ROCK ISLAND ARMORY M1911 A1FS 45ACP PISTOL RIA1232702 35 MAGNUM RESEARCH BFR 45LC/410 REVOLVER JT11455 BFR 36 MAGNUM RESEARCH BFR 50AE REVOLVER JT08038 BFR 37 MAGNUM RESEARCH BFR 500S&W REVOLVER JT07542 BFR 38 WEBLEY MK IV .38S&W REVOLVER A34264 39 CHIAPPA FA RHINO 40DS .357MAG REVOLVER RH02026 40 EAA WITNESS 40S&W PISTOL EA52095 41 EAA WITNESS -

Firearms Removal/Retrieval in Cases of Domestic Violence

1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................ 5 NOTES ON THE TEXT ..................................................................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 14 SCOPE OF THE REPORT ................................................................................................................. 14 DOMESTIC VIOLENCE HOMICIDE DATA............................................................................................. 14 Chart 1 ................................................................................................................................... 15 WHY THIS REPORT IS NECESSARY .................................................................................................. 16 AUTHORITY FOR REMOVAL/RETRIEVAL .................................................................................. 17 CIVIL PROTECTIVE ORDERS ........................................................................................................... 17 Explicit Authority ...................................................................................................................... 17 Figure 1 ................................................................................................................................. -

SA VZ. 61 Pistol INSTRUCTIONS MANUAL

Sa vz. 61 Pistol cal. 7.65 mm Br. cal. 9 mm Br. cal. 9 mm Makarov cal. 22 LR Instructions Manual WARNING! READ THE INSTRUCTIONS IN THIS MANUAL BEFORE USING THIS FIREARM. Safety Instructions Sa vz. 61 Pistol Instruction Manual Content: WARNING! 1. Carefully read the instructions and warnings in this Instruction Manual before using this firearm. Failure to follow the Part I. Description of the design of the Sa vz. 61 Pistol ...................................... 4 instructions in this Manual could result in the following: death or serious bodily injury to the operator, death or serious Chapter 1 General ...................................................................................................................................4 bodily injury to other, and demage to property. 1. Purpose and features of Sa vz. 61 Pistol 2. In a addition to studying and thoroughly understanding this Manual, ensure safety training is received from a com 2. Characteristics of Sa vz. 61 Pistol petent fireamrsm instructor before handling or using this firearm. Czech Small Arms, s.r.o. shall not be liable for any Chapter 2 Description of main parts of Sa vz. 61 Pistol .....................................................................................5 injury to persons or any damage to property resulting from the use of this friearms. 1. Barrel 3. This Instruction Manual must accompany the firearms at all times and be transferred with the firearm in the event 2. Receiver cover of a change in ownership, or when the firearm is loaned or presented to another person. 3. Sights 4. Always ensure the firearm and ammunition is kept away from children adn unauthorized persons by keeping the locked 4. Bolt up. SAFETY IS YOUR RESPONSIBILITY AT ALL TIMES! 5.