Searching for Solitude in the Wilderness of Southeast Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness in Southeastern Alaska: a History

Wilderness in Southeastern Alaska: A History John Sisk Today, Southeastern Alaska (Southeast) is well known remoteness make it wild in the most definitive sense. as a place of great scenic beauty, abundant wildlife and The Tongass encompasses 109 inventoried roadless fisheries, and coastal wilderness. Vast expanses of areas covering 9.6 million acres (3.9 million hectares), wild, generally undeveloped rainforest and productive and Congress has designated 5.8 million acres (2.3 coastal ecosystems are the foundation of the region’s million hectares) of wilderness in the nation’s largest abundance (Fig 1). To many Southeast Alaskans, (16.8 million acre [6.8 million hectare]) national forest wilderness means undisturbed fish and wildlife habitat, (U.S. Forest Service [USFS] 2003). which in turn translates into food, employment, and The Wilderness Act of 1964 provides a legal business. These wilderness values are realized in definition for wilderness. As an indicator of wild subsistence, sport and commercial fisheries, and many character, the act has ensured the preservation of facets of tourism and outdoor recreation. To Americans federal lands displaying wilderness qualities important more broadly, wilderness takes on a less utilitarian to recreation, science, ecosystem integrity, spiritual value and is often described in terms of its aesthetic or values, opportunities for solitude, and wildlife needs. spiritual significance. Section 2(c) of the Wilderness Act captures the essence of wilderness by identifying specific qualities that make it unique. The provisions suggest wilderness is an area or region characterized by the following conditions (USFS 2002): Section 2(c)(1) …generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable; Section 2(c)(2) …has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; Section 2(c)(3) …has at least five thousand acres of land or is of sufficient FIG 1. -

Public Law 96-487 (ANILCA)

APPENDlX - ANILCA 587 94 STAT. 2418 PUBLIC LAW 96-487-DEC. 2, 1980 16 usc 1132 (2) Andreafsky Wilderness of approximately one million note. three hundred thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge" dated April 1980; 16 usc 1132 {3) Arctic Wildlife Refuge Wilderness of approximately note. eight million acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "ArcticNational Wildlife Refuge" dated August 1980; (4) 16 usc 1132 Becharof Wilderness of approximately four hundred note. thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "BecharofNational Wildlife Refuge" dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 (5) Innoko Wilderness of approximately one million two note. hundred and forty thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Innoko National Wildlife Refuge", dated October 1978; 16 usc 1132 (6} Izembek Wilderness of approximately three hundred note. thousand acres as �enerally depicted on a map entitied 16 usc 1132 "Izembek Wilderness , dated October 1978; note. (7) Kenai Wilderness of approximately one million three hundred and fifty thousand acres as generaJly depicted on a map entitled "KenaiNational Wildlife Refuge", dated October 16 usc 1132 1978; note. (8) Koyukuk Wilderness of approximately four hundred thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "KoxukukNational Wildlife Refuge", dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 (9) Nunivak Wilderness of approximately six hundred note. thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Yukon DeltaNational Wildlife Refuge", dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 {10} Togiak Wilderness of approximately two million two note. hundred and seventy thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Togiak National Wildlife Refuge", dated July 16 usc 1132 1980; note. -

2018 Uncruise Adventures Brochure

October 2017 Adventure Cruises Define Your to April 2019 22 to 86 Guests Un-nessSM ALASKA | MEXICO | HAWAIIAN ISLANDS | COSTA RICA | PANAMÁ | GALÁPAGOS | COLUMBIA & SNAKE RIVERS | WASHINGTON | BRITISH COLUMBIA Contents Define Your Un-ness 3 Small Ships, BIG Adventures 5 Adventure 6 Place 8 Connection 10 Finding Our Un-ness 12 Unparalleled Value 14 Ready. Set. Go. 16 Theme Cruises 18 Wellness Cruises 20 Family Discoveries 22 Solo Travel 23 Groups & Charters 24 Sailing Calendar 26 COSTA RICA & PANAMÁ 28 MEXICO’S SEA OF CORTÉS 40 HAWAIIAN ISLANDS 48 GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS 56 COLUMBIA & SNAKE RIVERS 64 PACIFIC NORTHWEST 72 ALASKA 82 Life On Board 116 Wining & Dining 118 The Fleet 122 Small Ship Comparison 142 What’s Included 144 Reservation Information 145 Responsible Travel & Affiliations 146 Welcome Aboard 147 2 UnCruise.com Define Your Un-nessSM [uhn-nis] To break away from the masses. Challenge. Freely used to release, exemplify, or intensify a force or quality. To engage, connect, and explore unique places, oneself, and with others on a most uncommon adventure. Snapshot: I found my happy place. unique. 3 “Exceeded expectations. Thanks to the crew—you are fabulous. Only downside? My cheeks hurt from smiling. Awesome, fantastic!” -Nancy D; Silver Lake, NH (Alaska 2016) 4 UnCruise.com Snapshot: (L) Best to pack your Alaska tennis shoes. (R) Go with the flow. Small Ships, BIG Adventures A crew member shows you to your cabin. After a short time getting situated, gain your bearings with a spin around the ship. Then head to the lounge for a glass of bubbly and to meet your shipmates. -

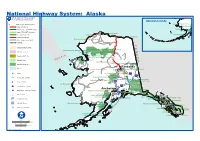

National Highway System: Alaska U.S

National Highway System: Alaska U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration Aleutian Islands Eisenhower Interstate System Lake Clark National Preserve Lake Clark Wilderness Other NHS Routes Non-Interstate STRAHNET Route Katmai National Preserve Katmai Wilderness Major STRAHNET Connector Lonely Distant Early Warning Station Intermodal Connector Wainwright Dew Station Aniakchak National Preserve Barter Island Long Range Radar Site Unbuilt NHS Routes Other Roads (not on NHS) Point Lay Distant Early Warning Station Railroad CC Census Urbanized Areas AA Noatak Wilderness Gates of the Arctic National Park Cape Krusenstern National Monument NN Indian Reservation Noatak National Preserve Gates of the Arctic Wilderness Kobuk Valley National Park AA Department of Defense Kobuk Valley Wilderness AA D II Gates of the Arctic National Preserve 65 D SSSS UU A National Forest RR Bering Land Bridge National Preserve A Indian Mountain Research Site Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Park Service College Fairbanks Water Campion Air Force Station Fairbanks Fortymile Wild And Scenic River Fort Wainwright Fort Greely (Scheduled to close) Airport A2 4 Denali National Park A1 Intercity Bus Terminal Denali National PreserveDenali Wilderness Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park and Preserve Tatalina Long Range Radar Site Wrangell-Saint Elias National Preserve Ferry Terminal A4 Cape Romanzof Long Range Radar Site Truck/Pipeline Terminal A1 Anchorage 4 Wrangell-Saint Elias Wilderness Multipurpose Passenger Facility Sparrevohn Long -

KMD Economic Feasibility

U. S. Department of the Interior SLM-Alaska Open File Report 68 Bureau of Land Management BLM/AK/ST-98/006+3090+930 February 1998 Alaska State Office 222 West 7th, #13 Anchorage, Alaska 99513 Economic Feasibility of Mining in the Chichagof and Baranof Islands Area, Southeast Alaska James R. Coldwell Author James R. Coldwell is a mining engineer in the Division of Lands, Minerals and Resources, working for the Juneau Mineral Resources Team, Bureau of Land Management, Juneau Alaska. Cover Photo Chichagof Mine, circa 1930, photograph by E. Andrews. From 1906-1942, the Chichagof Mine produced about 20,500 kg of gold from over 540,000 mt of ore. The mine closed in 1942 due to shortages of men and equipment created by World War II. Open File Reports Open File Reports identify the results of inventories or other investigations that are made available to the public outside the formal BLM-Alaska technical publication series. These reports can include preliminary or incomplete data and are not published and distributed in quantity. The reports are available at BLM offices in Alaska, and the USDI Resources Library in Anchorage, various libraries of the University of Alaska, and other selected locations. Copies are also available for inspection at the USDI Natural Resource Library in Washington, D.C. and at the BLM Service Center Library in Denver. Economic Feasibility of Mining in the Chichagof and Baranof Islands Area, Southeast Alaska James R. Coldwell Bureau of Land Management Alaska State Office Open File Report 68 Anchorage, Alaska 99513 February 1998 i CONTENTS Abstract.............................................................. 1 Introduction.......................................................... -

2008 ANNUAL REPORT SARAH PALIN, Governor

STATE OF ALASKA CITIZENS' ADVISORY COMMISSION ON FEDERAL AREAS 2008 ANNUAL REPORT SARAH PALIN, Governor 3700AIRPORT WAY CITIZENS' ADVISORY COMMISSION FAIRBANKS, ALASKA 99709 ON FEDERAL AREAS PHONE: (907) 374-3737 FAX: (907)451-2751 Dear Reader: This is the 2008 Annual Report of the Citizens' Advisory Commission on Federal Areas to the Governor and the Alaska State Legislature. The annual report is required by AS 41.37.220(f). INTRODUCTION The Citizens' Advisory Commission on Federal Areas was originally established by the State of Alaska in 1981 to provide assistance to the citizens of Alaska affected by the management of federal lands within the state. In 2007 the Alaska State Legislature reestablished the Commission. 2008 marked the first year of operation for the Commission since funding was eliminated in 1999. Following the 1980 passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), the Alaska Legislature identified the need for an organization that could provide assistance to Alaska's citizens affected by that legislation. ANILCA placed approximately 104 million acres of federal public lands in Alaska into conservation system units. This, combined with existing units, created a system of national parks, national preserves, national monuments, national wildlife refuges and national forests in the state encompassing more than 150 million acres. The resulting changes in land status fundamentally altered many Alaskans' traditional uses of these federal lands. In the 28 years since the passage of ANILCA, changes have continued. The Federal Subsistence Board rather than the State of Alaska has assumed primary responsibility for regulating subsistence hunting and fishing activities on federal lands. -

Revised Sitka District Coastal Management Program, Public Use

..-------REVISED-------...-.... SITKA DISTRICT COASTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAM PUBLIC USE MANAGEMENT PLA~N COASTAL ZONE INFORMATION CENTER PUBLIC HEARING DRAFT Significant Amendment -- July, 1990 Draft City and Borough of Sitka 304 ~AKE ~TREj:T. SITKA 1 ALASKA. 99835 The Sitka District Coastal Management Program invites you to read and comment on this Public Hearing Draft of the Sitka Public Use Management Plan. The Plan is being proposed as a Significant Amendment to the Sitka Coastal Management Program by the Coastal Management Citizens committee. The Committee initially recommended its development during the revision of the Sitka District Program in 1987 to provide special management policies for specific geographic locations considered as uniquely significant recreational and subsistence use areas. The Citizens Committee reconvened in spring, 1990, to develop criteria for selection of these sites, to make a preliminary selection of sites, and to recommend policies to address management concerns. The proposed policies are the major component of the Public Use Management Plan, in that they will provide both management guidelines and enforceable policies to all the land and water management agencies with jurisdiction over the special management sites. You are especially encouraged to comment on the proposed or additional policies and recommend other areas in the Sitka Coastal District which you believe meet the test for "uniqueness" under the criteria for selection as special management sites, as well as a thorough explanation or justification of the proposal. Your comments will assist the Citizens Committee in making final recommendations for the Public Use Management Plan. Your comments are important to us. Please make them in writing to: Marlene Campbell, Coastal District Coordinator City and Borough of Sitka 304 Lake Street Sitka, Alaska 99835. -

Page 1464 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1132

§ 1132 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 1464 Department and agency having jurisdiction of, and reports submitted to Congress regard- thereover immediately before its inclusion in ing pending additions, eliminations, or modi- the National Wilderness Preservation System fications. Maps, legal descriptions, and regula- unless otherwise provided by Act of Congress. tions pertaining to wilderness areas within No appropriation shall be available for the pay- their respective jurisdictions also shall be ment of expenses or salaries for the administra- available to the public in the offices of re- tion of the National Wilderness Preservation gional foresters, national forest supervisors, System as a separate unit nor shall any appro- priations be available for additional personnel and forest rangers. stated as being required solely for the purpose of managing or administering areas solely because (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classi- they are included within the National Wilder- fications as primitive areas; Presidential rec- ness Preservation System. ommendations to Congress; approval of Con- (c) ‘‘Wilderness’’ defined gress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Ea- A wilderness, in contrast with those areas gles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado where man and his own works dominate the The Secretary of Agriculture shall, within ten landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where years after September 3, 1964, review, as to its the earth and its community of life are un- suitability or nonsuitability for preservation as trammeled by man, where man himself is a visi- wilderness, each area in the national forests tor who does not remain. An area of wilderness classified on September 3, 1964 by the Secretary is further defined to mean in this chapter an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its of Agriculture or the Chief of the Forest Service primeval character and influence, without per- as ‘‘primitive’’ and report his findings to the manent improvements or human habitation, President. -

Page 1517 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1131 (Pub. L

Page 1517 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1131 (Pub. L. 88–363, § 10, July 7, 1964, 78 Stat. 301.) Sec. 1132. Extent of System. § 1110. Liability 1133. Use of wilderness areas. 1134. State and private lands within wilderness (a) United States areas. The United States Government shall not be 1135. Gifts, bequests, and contributions. liable for any act or omission of the Commission 1136. Annual reports to Congress. or of any person employed by, or assigned or de- § 1131. National Wilderness Preservation System tailed to, the Commission. (a) Establishment; Congressional declaration of (b) Payment; exemption of property from attach- policy; wilderness areas; administration for ment, execution, etc. public use and enjoyment, protection, preser- Any liability of the Commission shall be met vation, and gathering and dissemination of from funds of the Commission to the extent that information; provisions for designation as it is not covered by insurance, or otherwise. wilderness areas Property belonging to the Commission shall be In order to assure that an increasing popu- exempt from attachment, execution, or other lation, accompanied by expanding settlement process for satisfaction of claims, debts, or judg- and growing mechanization, does not occupy ments. and modify all areas within the United States (c) Individual members of Commission and its possessions, leaving no lands designated No liability of the Commission shall be im- for preservation and protection in their natural puted to any member of the Commission solely condition, it is hereby declared to be the policy on the basis that he occupies the position of of the Congress to secure for the American peo- member of the Commission. -

Adam Z. Andis 1223 Helen Ave #1 | Missoula, MT 59801 | [email protected] | 812-344-4055

Adam Z. Andis 1223 Helen Ave #1 | Missoula, MT 59801 | [email protected] | 812-344-4055 Personal Statement: My experience in the environmental field during four years of study and five years in an environmental NGO have solidified my lifelong passion for conservation. In addition to education and work, I have gained insights into environmental problems and solution as a board member of a national conservation group. I now look forward to refining my skills set through research and graduate scholarship to better prepare myself for a continued career in the conservation field. My strong mid-western work ethic, coupled with communication skills, management experience and ability to work in a team are assets I will bring to the program. I value independent thinking and creative problem solving above all else and apply rigorous discipline to following through with my responsibilities. Education: M.Sc. Environmental Studies emphasis Watershed Conservation University of Montana | Missoula, Montana | 2014-2016 (expected) Research interests: I am interested in mitigating anthropogenic effects on watershed systems. My thesis research looks at ways to minimize or alter landscape disturbances for migration and dispersal of herpetofauna. Relevant Coursework: Hydrology, Aquatic Ecology with field components, Applied Watershed Conservation B.S. Environmental Studies emphasis Wilderness Philosophy Northland College | Ashland, Wisconsin | 2005-2008 Cumulative GPA: 3.77 Honors and Distinctions • Magna Cum Laude • Dean's List, 2007-2009 (all applicable -

2019 Uncruise Adventures Brochure

National Parks by Water Preserving Our Past. Protecting Our Future. Unrivaled. 1 100 Years of Advocacy Dear Friend, National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA)—a powerful, nonpartisan organization—has worked to defend America’s most significant places since 1919. Our founders knew that national parks needed a voice to protect them. And that’s still the case today. We proudly carry on this important mission with supporters like you and encourage the next generation to care for them as much as we do. With our shared commitment to protecting fragile ecosystems and local communities, our partnership with UnCruise Adventures offers you unforgettable travel opportunities. For more than 20 years, UnCruise’s small ship experiences have inspired an appreciation of local cultures and the natural world. Find your connection to our natural heritage—by kayak, hike, bushwhack, and skiff ride, and know you’re helping NPCA ensure that future generations can experience these treasured places. Theresa Pierno President & CEO National Parks Conservation Association 2 Un-Cruise® – Panama and Costa Rica November 2018-April 2020 READY. SET. GO. get active & inspired launching NEW in 2019 small ship adventures warm- WILD hearted Places crew ALASKA | COLUMBIA & SNAKE RIVERS | PACIFIC NORTHWEST | HAWAIIAN ISLANDS | MEXICO | COSTA RICA & PANAMÁ | GALÁPAGOS “Perfect balance of fun and relaxed activities. The educational aspect added high value. The crew soon felt like family and friends yet always acted with top professional standards. The entire experience was unforgettable.” — Kazemaru B; Hakalau, HI (Hawaii 2016) 4 UnCruise.com Adventure The spirit of adventure comes in many forms, and all are welcome. An avid kayaker? A snorkeling newbie? Long-distance hiker or slow-paced beachcomber? Your expedition team helps you find the right fit. -

Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act

APPENDIX - ANILCA 537 XXIII. APPENDIX 1. Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act PUBLIC LAW 96–487—DEC. 2, 1980 94 STAT. 2371 Public Law 96–487 96th Congress An Act To provide for the designation and conservation of certain public lands in the State Dec. 2, 1980 of Alaska, including the designation of units of the National Park, National [H.R. 39] Wildlife Refuge, National Forest, National Wild and Scenic Rivers, and National Wilderness Preservation Systems, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Alaska National SECTION 1. This Act may be cited as the “Alaska National Interest Lands Interest Lands Conservation Act”. Conservation Act. TABLE OF CONTENTS 16 USC 3101 note. TITLE I—PURPOSES, DEFINITIONS, AND MAPS Sec. 101. Purposes. Sec. 102. Definitions. Sec. 103. Maps. TITLE II—NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM Sec. 201. Establishment of new areas. Sec. 202. Additions to existing areas. Sec. 203. General administration. Sec. 204. Native selections. Sec. 205. Commercial fishing. Sec. 206. Withdrawal from mining. TITLE III—NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE SYSTEM Sec. 301. Definitions. Sec. 302. Establishment of new refuges. Sec. 303. Additions to existing refuges. Sec. 304. Administration of refuges. Sec. 305. Prior authorities. Sec. 306. Special study. TITLE IV—NATIONAL CONSERVATION AREA AND NATIONAL RECREATION AREA Sec. 401. Establishment of Steese National Conservation Area. Sec. 402. Administrative provisions. Sec. 403. Establishment of White Mountains National Recreation Area. Sec. 404. Rights of holders of unperfected mining claims. TITLE V—NATIONAL FOREST SYSTEM Sec. 501. Additions to existing national forests.