Oral Evidence: Post-Brexit Migration Policy, HC 857

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EU Renegotiation: Fighting for a Flexible Union How to Renegotiate the Terms of the UK’S Membership of the EU

EU Renegotiation: Fighting for a Flexible Union How to renegotiate the terms of the UK’s Membership of the EU (Quotation in title taken from President Glyn Gaskarth September 2013 ii © Civitas 2013 55 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QL Civitas is a registered charity (no. 1085494) and a company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales (no. 04023541) email: [email protected] Independence: Civitas: Institute for the Study of Civil Society is a registered educational charity (No. 1085494) and a company limited by guarantee (No. 04023541). Civitas is financed from a variety of private sources to avoid over-reliance on any single or small group of donors. All the Institute’s publications seek to further its objective of promoting the advancement of learning. The views expressed are those of the authors, not of the Institute. i Contents Acknowledgements ii Foreword, David Green iii Executive Summary iv Background 1 Introduction 3 Chapter One – Trade 9 Chapter Two – City Regulation 18 Chapter Three – Options for Britain 26 Chapter Four – Common Fisheries Policy 42 Chapter Five – National Borders and Immigration 49 Chapter Six – Foreign & Security Policy 58 Chapter Seven – European Arrest Warrant (EAW) 68 Conclusion 80 Bibliography 81 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Tamara Chehayeb Makarem and Susan Gaskarth for their support during the compilation of this paper and Dr David Green and Jonathan Lindsell of Civitas for their comments on the text. iii Foreword Our main aim should be the full return of our powers of self-government, but that can’t happen before the referendum promised for 2017. -

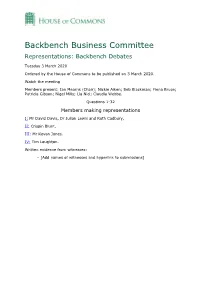

Backbench Business Committee Representations: Backbench Debates

Backbench Business Committee Representations: Backbench Debates Tuesday 3 March 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 3 March 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Ian Mearns (Chair); Nickie Aiken; Bob Blackman; Fiona Bruce; Patricia Gibson; Nigel Mills; Lia Nici; Claudia Webbe. Questions 1-32 Members making representations I: Mr David Davis, Dr Julian Lewis and Ruth Cadbury. II: Crispin Blunt. III: Mr Kevan Jones. IV: Tim Loughton. Written evidence from witnesses: – [Add names of witnesses and hyperlink to submissions] Mr David Davis, Dr Julian Lewis and Ruth Cadbury made representations. Q1 Member Chair: Good afternoon and welcome to the first sitting of the Backbench Business Committee in the 2020-21 parliamentary Session. We have four applications this afternoon. The first is led by Mr David Davis, Ruth Cadbury and Dr Julian Lewis. Welcome to you all. The first application is on the loan charge, and the Amyas Morse review and subsequent Government action. Witness Mr Davis: Thank you, Mr Chairman. The loan charge is an important issue of natural justice, and it cuts across party divides. You will have seen that our 46 signatories include Conservatives, Labour, Lib Dems, SNP and DUP. We have had two previous debates on the charge, one in Westminster Hall and one in the main Chamber. The Westminster Hall debate was in 2018 and had, I think, 28 or 29 speakers. The main Chamber debate was on 4 April 2019 and also had 28 speakers, so there is a lot of interest in this. The reason for that is that it affects roughly 50,000 people, so lots of people in every constituency—I will not go into the details of the argument unless you want me to, Mr Chairman. -

OPENING PANDORA's BOX David Cameron's Referendum Gamble On

OPENING PANDORA’S BOX David Cameron’s Referendum Gamble on EU Membership Credit: The Economist. By Christina Hull Yale University Department of Political Science Adviser: Jolyon Howorth April 21, 2014 Abstract This essay examines the driving factors behind UK Prime Minister David Cameron’s decision to call a referendum if the Conservative Party is re-elected in 2015. It addresses the persistence of Euroskepticism in the United Kingdom and the tendency of Euroskeptics to generate intra-party conflict that often has dire consequences for Prime Ministers. Through an analysis of the relative impact of political strategy, the power of the media, and British public opinion, the essay argues that addressing party management and electoral concerns has been the primary influence on David Cameron’s decision and contends that Cameron has unwittingly unleashed a Pandora’s box that could pave the way for a British exit from the European Union. Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank the Bates Summer Research Fellowship, without which I would not have had the opportunity to complete my research in London. To Professor Peter Swenson and the members of The Senior Colloquium, Gabe Botelho, Josh Kalla, Gabe Levine, Mary Shi, and Joel Sircus, who provided excellent advice and criticism. To Professor David Cameron, without whom I never would have discovered my interest in European politics. To David Fayngor, who flew halfway across the world to keep me company during my summer research. To my mom for her unwavering support and my dad for his careful proofreading. And finally, to my adviser Professor Jolyon Howorth, who worked with me on this project for over a year and a half. -

Brexit Interview: Raoul Ruparel

Raoul Ruparel Special Advisor to the Prime Minister on Europe August 2018 – July 2019 Special Advisor to the Secretary of State for the Department for Exiting the EU October 2016 – July 2018 Co-Director, Open Europe May 2015 – October 2016 11 August 2020 The renegotiation and the referendum UK in a Changing Europe (UKICE): How influential, do you think, Open Europe was in shaping David Cameron’s approach to the Bloomberg speech and the renegotiation? Raoul Ruparel (RR): I think we were fairly influential. Our chairman at the time, Lord Leach, who sadly passed away, was quite close to Cameron, especially on EU issues, and so had quite a lot of say in some of the parts of the Bloomberg speech. Obviously, Mats Persson also had some input to the speech and then went to work for Cameron on the reform agenda. That being said, before Mats got into Number 10 under Cameron, I think a lot of it was already set. The ambition was already set relatively low in terms of the type of reform Cameron was going to aim for. So I think there was some influence. Certainly, I think Open Europe had an impact in trying to bridge that path between the Eurosceptics and those who wanted to see Brexit, and were in that camp from quite early on, and the wider Page 1/30 public feeling of concern over immigration and other aspects. Yes, there certainly was something there in terms of pushing the Cameron Government in the direction of reform. I don’t think it’s something that Open Europe necessarily created, I think they were looking for something in that space and we were there to fill it. -

Brexit and the Future of the US–EU and US–UK Relationships

Special relationships in flux: Brexit and the future of the US–EU and US–UK relationships TIM OLIVER AND MICHAEL JOHN WILLIAMS If the United Kingdom votes to leave the European Union in the referendum of June 2016 then one of the United States’ closest allies, one of the EU’s largest member states and a leading member of NATO will negotiate a withdrawal from the EU, popularly known as ‘Brexit’. While talk of a UK–US ‘special relation- ship’ or of Britain as a ‘transatlantic bridge’ can be overplayed, not least by British prime ministers, the UK is a central player in US–European relations.1 This reflects not only Britain’s close relations with Washington, its role in European security and its membership of the EU; it also reflects America’s role as a European power and Europe’s interests in the United States. A Brexit has the potential to make a significant impact on transatlantic relations. It will change both the UK as a country and Britain’s place in the world.2 It will also change the EU, reshape European geopolitics, affect NATO and change the US–UK and US–EU relationships, both internally and in respect of their place in the world. Such is the potential impact of Brexit on the United States that, in an interview with the BBC’s Jon Sopel in summer 2015, President Obama stated: I will say this, that having the United Kingdom in the European Union gives us much greater confidence about the strength of the transatlantic union and is part of the corner- stone of institutions built after World War II that has made the world safer and more prosperous. -

IEA Brexit Prize: the Plan to Leave the European Union by 2020 by Daniel

IEA Brexit Prize: The plan to leave the European Union by 2020 by Daniel. C. Pycock FINALIST: THE BREXIT PRIZE 2014 IEA BREXIT PRIZE 3 3 Executive Summary 3 A Rebuttal to Targeting Exchange Rates with Monetary Policy I – THE CONSTITUTIONAL PROCESS FOR LEAVING THE EUROPEAN UNION 6 V – FISCAL POLICY: SPENDING PRIORITIES The Constitutional Processes of Leaving the AND TAX REFORMS 28 European Union On the repatriation of, and necessary reforms to, The articles of the proposed “Treaty of London” Value Added Tax 2017 On the Continuation of Current Corporation Tax The impact of BREXIT on the United Trends, and Reforms to Individual Taxation Kingdom’s Trade Position On The Desirable Restructuring of Income Tax The European Union, Unemployment, and Rates: The History of the Laffer Curve Trading Position post-withdrawal On Government Spending and the Need to Improve GAAP use in Cost Calculations II – THE IMPACT OF BREXIT ON THE UNITED KINGDOM’S TRADE POSITION 10 Suggestions for savings to be made in Defence, Health, Welfare, and Overall Spending Trends in UK Trade with the EU and the Commonwealth, and their shares of Global VI.I – ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE 34 GDP The Mismatch of Policy with Hypothesis: Climate The UK and the Commonwealth: The Return of Change, Energy and the Environment an Imperial Trading Zone? The Unintended Consequences of the European The Trends of Trading: The UK’s Future Union’s Environmental Policies. Exports & Those of Trading Organisations Fracking, Fossil Fuels, and Feasibility: How to Unemployment in the European Union, -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Interim Report July 2018-March 2019

Q3 Interim report July 2018-March 2019 The “Company” or “Hamlet Pharma” refers to Hamlet Pharma AB, corp. reg. no. 556568-8958 Significant events in the third quarter During the period, the Company delivered significant results. 1. New capital injection On February 1, 2019, the Board decided to implement a private placement of shares, to generate an initial contribution of approximately MSEK 10, with an option to inject an additional MSEK 25 into the Company by exercising subscription warrants until Q1 2020. The decision is in line with a resolution adopted by the Annual General Meeting (AGM) on November 22, 2018, which authorized the Board to seek new funding. The capital injection will enable Hamlet Pharma to continue its operations, start new clinical activities and develop the Alpha1H candidate into a new drug. 2. Bladder cancer trial In the third quarter, we were focused on the continued recruitment of patients to include the 40 patients defined in the protocol. The doctors and staff involved in the trial are doing a fantastic job. Our plan, as previously communicated, is to end the clinical trial in June. We are therefore in a very labor-intensive period and performing continuous assessments of the samples that form the basis of the clinical trial analysis. By working pro-actively, we are hoping to have materials ready for a prompt analysis of the results following the last subject, last visit. 3. Follow-up of long-term effects On February 7, the Company announced that the Czech regulator had approved an extension of the ongoing trial whereby patients would be tracked for an additional two years after an initial evaluation. -

The European Conservatives and Reformists in the European Parliament

The European Conservatives and Reformists in the European Parliament Standard Note: SN/IA/6918 Last updated: 16 June 2014 Author: Vaughne Miller Section International Affairs and Defence Section Parties are continuing negotiations to form political groups in the European Parliament (EP) following European elections on 22-25 May 2014. This note looks at the future composition of the European Conservatives and Reformists group (ECR), which was established by UK Conservatives when David Cameron took them out of the centre-right EPP-ED group in 2009. It also considers what the entry of the German right-wing Alternative für Deutschland group into the ECR group might mean for Anglo-German relations. The ECR might become the third largest political group in the EP, although this depends on support for the Liberals and Democrats group. The final number and composition of EP political groups will not be known until after 24 June 2014, which is the deadline for registering groups. For detailed information on the EP election results, see Research paper 14/32, European Parliament Elections 2014, 11 June 2014. This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. It should not be relied upon as being up to date; the law or policies may have changed since it was last updated; and it should not be relied upon as legal or professional advice or as a substitute for it. A suitably qualified professional should be consulted if specific advice or information is required. -

Domestic Abuse Bill

DOMESTIC ABUSE BILL How Hestia’s UK SAYS NO MORE campaign has worked to ensure that the Domestic Abuse Bill recognises and supports children affected by domestic abuse and enshrines the role that employers play in supporting employees experiencing domestic abuse. A TIMELINE 2017 21st June: The Queen’s Speech outlines plans for a new Domestic Abuse Bill. 2018 17th April: UK SAYS NO MORE publishes a ‘Charter on Prevention’, calling on 17th April: Labour MP for Swansea East Parliamentarians to support key components and newly appointed UK SAYS NO MORE in the Bill. This includes greater mental health champion Carolyn Harris is the first MP support for children who have experienced to support the Charter on Prevention. domestic abuse. 17th May: During oral questions, Carolyn Harris asks then Minister for Women and 23rd May: UK SAYS NO MORE hosts the Equalities Penny Mordaunt MP what support Charter on Prevention rally in Parliament the Government will provide to children after weeks spent calling on MPs to affected by domestic abuse. sign the Charter and ensure support for children is enshrined in the Bill. 24th May: More than 100 cross-party MPs and Parliamentarians sign up to be Champions of the 24th May: New data from Hestia and Charter on Prevention, asking the government to Opinium reveals that more than half of Brits ensure children aren’t forgotten in the Bill and that who experience domestic abuse as children employers hold a role in responding to domestic abuse. will go on to experience it as adults. Champion Carolyn Harris MP asks Theresa May to consider our recommendations. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK Civil Action No. COMPLAINT MONTANA BOARD of INVESTMENT

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK MONTANA BOARD OF INVESTMENTS; Civil Action No. --- TEACHER RETIREMENT SYSTEM OF TEXAS; CALIFORNIA PUBLIC COMPLAINT EMPLOYEES' RETIREMENT SYSTEM; CALIFORNIA STATE TEACHERS' JURY TRIAL DEMANDED RETIREMENT SYSTEM; THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA; ARIZONA STATE RETIREMENT SYSTEM; CAISSE DE D:EPOT ET PLACEMENT DU QUEBEC; THRIVENT LARGE CAP GROWTH PORTFOLIO (f/k/a Lutheran Brotherhood Employees' Equities Fund); THRIVENT LARGE CAP GROWTH PORTFOLIO (f/k/a/ Growth Portfolio); THRIVENT LARGE CAP GROWTH PORTFOLIO (f/k/a Investors Growth Portfolio); THRIVENT FINANCIAL FOR LUTHERANS FOUNDATION (f/k/a Lutheran Brotherhood Foundation); THRIVENT FINANCIAL FOR LUTHERANS (f/k/a Lutheran Brotherhood); THRIVENT LARGE CAP STOCK FUND (f/k/a Lutheran Brotherhood Fund); THRIVENTLARGECAPGROWTHFUND (:f/k/a Lutheran Brotherhood Growth Fund); THRIVENTLARGECAPVALUEFUND (f/k/a Lutheran Brotherhood Value Fund); THRIVENT LARGE CAP VALUE PORTFOLIO (f/k/a Value Portfolio); THRIVENT LARGE CAP VALUE PORTFOLIO (f/k/a Equity Income Portfolio); THRIVENT LARGE CAP GROWTH FUND (f/k/a The AAL Aggressive Growth Fund); THRIVENT LARGE CAP GROWTH FUND (f/k/a The AAL Technology Stock Fund); THRIVENT LARGE CAP GROWTH PORTFOLIO (:f/k/a AAL Aggressive Growth Portfolio); THRIVENT BALANCED FUND (f/k/a The AAL Balanced Fund); THRIVENT LARGE CAP STOCK FUND (f/k/a The AAL Ca ital Growth Fund); THRIVENT LARGE CAP VALUE FUND (f/k/a The AAL Equity Income Fund); THRIVENT LARGE CAP STOCK PORTFOLIO (f/k/a Capital Growth Portfolio); THRIVENT PARTNER TECHNOLOGY PORTFOLIO (f/k/a Technology Stock Portfolio); THRIVENT LARGE CAP INDEX FUND-I (f/k/a The AAL Large Company Index Fund); THRIVENT LARGE CAP INDEX FUND (f/k/a The AAL Large Company Index Fund II); THRIVENT BALANCED PORTFOLIO (f/k/a Balanced Portfolio); AND THRIVENT LARGE CAP INDEX PORTFOLIO (f/k/a Large Company Index Portfolio); AMERICAN CENTURY MUTUAL FUNDS, INC.