British Conservatism, Family Law and the Problem of Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Father of the House Sarah Priddy

BRIEFING PAPER Number 06399, 17 December 2019 By Richard Kelly Father of the House Sarah Priddy Inside: 1. Seniority of Members 2. History www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 06399, 17 December 2019 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Seniority of Members 4 1.1 Determining seniority 4 Examples 4 1.2 Duties of the Father of the House 5 1.3 Baby of the House 5 2. History 6 2.1 Origin of the term 6 2.2 Early usage 6 2.3 Fathers of the House 7 2.4 Previous qualifications 7 2.5 Possible elections for Father of the House 8 Appendix: Fathers of the House, since 1901 9 3 Father of the House Summary The Father of the House is a title that is by tradition bestowed on the senior Member of the House, which is nowadays held to be the Member who has the longest unbroken service in the Commons. The Father of the House in the current (2019) Parliament is Sir Peter Bottomley, who was first elected to the House in a by-election in 1975. Under Standing Order No 1, as long as the Father of the House is not a Minister, he takes the Chair when the House elects a Speaker. He has no other formal duties. There is evidence of the title having been used in the 18th century. However, the origin of the term is not clear and it is likely that different qualifications were used in the past. The Father of the House is not necessarily the oldest Member. -

KMEP Briefing Note: INFRASTRUCTURE SUMMIT 2017 Feedback Page 1

KMEP Briefing Note: INFRASTRUCTURE SUMMIT 2017 feedback Page 1 KMEP Infrastructure Summit: 20 January 2017 Overview of the event Presentations were given by local businessmen on the In January, the Kent and Medway Economic priority rail, road and skills infrastructure that KMEP Partnership (KMEP) met Kent and Medway’s MPs. wishes to see built. The summit’s main purpose was to agree a list of There was then an opportunity to debate the priority infrastructure that we could collectively presentations’ content, and for MPs to ask questions. lobby the Government for. This briefing note provides details about the event This briefing note now summarises the presentations: for those unable to attend. RAIL PRIORITY Who attended the conference? INFRASTRUCTURE MPs: Charlie Elphicke Sir Roger Gale Rt. Hon. Damian Green Which rail priorities did KMEP identify? Craig Mackinlay Kelly Tolhurst Crossrail should be extended to Ebbsfleet as a minimum, and preferably to Gravesend. The strategic From KMEP: narrative for the extension will be submitted to HM 55 local businessmen and women Treasury this month. 14 local Council Leaders or alternates Canterbury Christ Church University’s Vice- The South Eastern Franchise Tender should include Chancellor these requirements: MidKent College’s Principal Elongate High Speed trains in the peak to add capacity (trains should have 12-cars, not 6). What were the KMEP’s introductory messages at Provide new Ebbsfleet shuttle service to the summit? London with 2 trains per hour (tph) all day KMEP (otherwise -

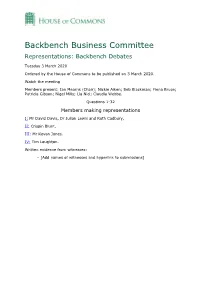

Backbench Business Committee Representations: Backbench Debates

Backbench Business Committee Representations: Backbench Debates Tuesday 3 March 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 3 March 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Ian Mearns (Chair); Nickie Aiken; Bob Blackman; Fiona Bruce; Patricia Gibson; Nigel Mills; Lia Nici; Claudia Webbe. Questions 1-32 Members making representations I: Mr David Davis, Dr Julian Lewis and Ruth Cadbury. II: Crispin Blunt. III: Mr Kevan Jones. IV: Tim Loughton. Written evidence from witnesses: – [Add names of witnesses and hyperlink to submissions] Mr David Davis, Dr Julian Lewis and Ruth Cadbury made representations. Q1 Member Chair: Good afternoon and welcome to the first sitting of the Backbench Business Committee in the 2020-21 parliamentary Session. We have four applications this afternoon. The first is led by Mr David Davis, Ruth Cadbury and Dr Julian Lewis. Welcome to you all. The first application is on the loan charge, and the Amyas Morse review and subsequent Government action. Witness Mr Davis: Thank you, Mr Chairman. The loan charge is an important issue of natural justice, and it cuts across party divides. You will have seen that our 46 signatories include Conservatives, Labour, Lib Dems, SNP and DUP. We have had two previous debates on the charge, one in Westminster Hall and one in the main Chamber. The Westminster Hall debate was in 2018 and had, I think, 28 or 29 speakers. The main Chamber debate was on 4 April 2019 and also had 28 speakers, so there is a lot of interest in this. The reason for that is that it affects roughly 50,000 people, so lots of people in every constituency—I will not go into the details of the argument unless you want me to, Mr Chairman. -

Disposal Services Agency Annual Report and Accounts 2006-2007

Annual Report & Accounts 2006-2007 DisposalSMART 1 What is the Disposal Services Agency? The Disposal Services Agency (DSA) is the sole authority for the disposal process of all surplus defence equipment, with the exception of nuclear, land and buildings. The Agency targets potential markets particularly in developing countries in a pro-active manner; to enable them to procure formally used British defence equipment instead of equipment from other countries. The principal activity of the Agency is the provision of disposal and sales services to MoD and other parts of the public sector. These services include Government-to-Government Sales, Asset Realisation, Inventory Disposals, Site Clearances, Repayment Sales, Waste Management and Consultancy and Valuation Services. DSA’s Aim: To secure the best nancial return from the sale of surplus equipment and stores; to minimise the cost of sales and to operate as an intelligent contracting organisation with various agreements with British Industry and Commerce. DSA’s Mission: To provide Defence and other users with an agreed, effective and ef cient disposals and sales service in order to support UK Defence capability. DSA’s Vision: To be the best government Disposals organisation in the world. DisposalSMART Annual Report & Accounts 2006-2007 A Defence Agency of the Ministry of Defence Annual Report and Accounts 2006-2007 Presented to the House of Commons pursuant to section 7 of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 23rd July 2007 HC 705 -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

February 2020 Minutes

Minutes from British-Japan Parliamentary Group AGM Date: Monday 24th February 2020 Attending: Lord Bates, Lord Sassoon, Lord Pendry, Yvonne Forargue MP, Peter Bottomley MP, Baroness Healy of Primrose Hill, Lord Gilbert, Rt Hon Greg Clark MP, Baroness Hooper, Lord Taylor of Holbeach, Viscount Trenchard, Alex Sobel MP, Gary Sambrook MP, Heather Wheeler MP, Nigel Evans MP, David Simmons MP, Sir George Howarth, Kevin Hollinrake MP, Lord Howell, Sir Mark Hendrick MP, Craig Williams MP, Dr Lisa Cameron MP, Sir Mark Hendrick MP, Baroness D’Souza and Jeremy Hunt MP. Apologies received from: Viscount Waverley, Ian Paisley MP, Pauline Latham MP, Baroness Goudie, Rosie Cooper MP, Sir Graham Brady MP, Gareth Bacon MP, Lord Lansley, John Spellar MP, Flick Drummond MP, Douglas Chapman MP, Lord Campbell, Paul Howell MP, Dr Ben Spencer and Deidre Brock MP. The meeting was called to order at 1630. Election of Chair: Mr Nigel Evans MP, Proposed the Rt Hon Jeremy Hunt MP. Mr Hunt was elected unanimously. Election of Secretary: Only one nomination was received in the name of Sir Mark Hendrick MP. Sir Mark was elected unopposed (Proposed by the Chair). Election of Vice-Chairs: The following were proposed by the Chair and elected unanimously; Craig Williams MP (Con), Dr Lisa Cameron MP (SNP), Gary Sambrook MP (Con), Viscount Trenchard (Con), Lord Moynihan (Con), Lord Holmes (Unaffiliated), Viscount Waverley (Ind), Baroness Finlay (Ind), John Spellar MP (Lab), Lord Bates (Con), Sir Graham Brady MP (Con), Heather Wheeler MP (Con), Chris Elmore MP (Lab), David Morris MP (Con), Ian Paisley MP (DUP), Baroness Hooper (Con), Judith Cummins MP (Lab), Lord Pendry (Lab), Deidre Block (SNP) and Dr Ben Spencer MP (Con). -

United Kingdom Youth Parliament Debate 11Th November 2016 House of Commons

United Kingdom Youth Parliament Debate 11th November 2016 House of Commons 1 Youth Parliament11 NOVEMBER 2016 Youth Parliament 2 we get into our formal proceedings. Let us hope that Youth Parliament it is a great day. We now have a countdown of just over 40 seconds. I have already spotted a parliamentary colleague Friday 11 November 2016 here, Christina Rees, the hon. Member for Neath, whose parliamentary assistant will be addressing the Chamber erelong. Christina, welcome to you. [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] 11 am 10.54 am The Youth Parliament observed a two-minute silence. Mr Speaker: Welcome to the eighth sitting of the UK Thank you, colleagues. I call the Leader of the House [Applause.] Youth Parliament in the House of Commons Chamber. of Commons, Mr David Lidington. This marks the beginning of UK Parliament Week, a programme of events and activities which connects The Leader of the House of Commons (Mr David people with the United Kingdom Parliament. This year, Lidington): I thank you, Mr Speaker, and Members of more than 250 activities and events are taking place the YouthParliament. I think you and I would probably across the UK. The issues to be debated today were agree that the initial greetings we have received make a chosen by the annual Make Your Mark ballot of 11 to welcome contrast from the reception we may, at times, 18-year-olds. The British Youth Council reported that, get from our colleagues here during normal working once again, the number of votes has increased, with sessions. 978,216 young people casting a vote this year. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Appointment of the UK's Delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly of The

House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee Appointment of the UK’s delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe Second Report of Session 2015–16 HC 658 House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee Appointment of the UK’s delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe Second Report of Session 2015–16 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 5 January 2016 HC 658 Published on 14 January 2016 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee The Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the reports of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Administration and the Health Service Commissioner for England, which are laid before this House, and matters in connection therewith; to consider matters relating to the quality and standards of administration provided by civil service departments, and other matters relating to the civil service; and to consider constitutional affairs. Current membership Mr Bernard Jenkin MP (Conservative, Harwich and North Essex) (Chair) Ronnie Cowan (Scottish National Party, Inverclyde) Oliver Dowden (Conservative, Hertsmere) Paul Flynn (Labour, Newport West) Rt Hon Cheryl Gillan (Conservative, Chesham and Amersham) Kate Hoey (Labour, Vauxhall) Kelvin Hopkins (Labour, Luton North) Rt Hon David Jones (Conservative, Clwyd West) Gerald Jones (Labour, Merthyr Tydfil and Rhymney) Tom Tugendhat (Conservative, Tonbridge and Malling) Mr Andrew Turner (Conservative, Isle of Wight) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 146. -

House of Commons Monday 20 May 2013 Votes and Proceedings

No. 8 41 House of Commons Monday 20 May 2013 Votes and Proceedings The House met at 2.30 pm. PRAYERS. 1 Speaker’s Statement: Search of a Member’s office 2 Questions to the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions 3 Statement: Syria (Secretary William Hague) 4 Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Bill (Programme) (No. 2) Ordered, That the Order of 5 February 2013 (Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Bill (Programme)) be varied as follows: (1) Paragraphs 4, 5 and 6 of the Order shall be omitted. (2) Proceedings on Consideration and Third Reading shall be taken in two days in accordance with the following provisions of this Order. (3) Proceedings on Consideration shall be taken on the days shown in the first column of the following Table and in the order so shown. (4) Proceedings on Consideration shall (so far as not previously concluded) be brought to a conclusion at the times specified in the second column of the Table. Table Proceedings Time for conclusion of proceedings First day New Clauses relating to any of the following: 7.00pm (a) sex education, (b) conscientious or other objection to marriage of same sex couples, (c) equality law, (d) religious organisations’ opt-in to marriage of same sex couples, and (e) protection against compulsion to solemnize marriages of same sex couples or to carry out activities in relation to the solemnization of such marriages amendments to Clause 2 other than amendments to the definition of ‘relevant marriage’ in subsection (4), amendments to Clause 8, and amendments to Schedule 7 relating to section 403 of the Education Act 1996. -

Stein CV2018

ARLENE J. STEIN Department of Sociology, Rutgers University 045 Davison Hall, Douglass Campus, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 [email protected] EDUCATION 1993 Ph.D., 1985 M.A., Sociology, University of California, Berkeley 1980 B.A. History, Amherst College APPOINTMENTS Professor, Sociology, Rutgers University, 2011- Associate Professor, Sociology, Rutgers University, 2001-11 Graduate Faculty, Women’s and Gender Studies, Rutgers University, 2001- Associate Professor, Sociology, University of Oregon, September 2000-June 2001 Assistant Professor, Sociology, University of Oregon, September 1994-June 2000 Lecturer, Sociology, University of Essex (UK), January 1993-July 1994 RESEARCH INTERESTS Gender, sexuality, intimacy, LGBT studies, political culture, subjectivities, social movements, collective memory, public sociology, ethnography, narrative analysis. PUBLICATIONS Books Unbound: Transgender Men and the Remaking of Identity, Pantheon, 2018. Gender, Sexuality, and Intimacy: A Contexts Reader (Jodi O’Brien, co-editor), Sage, 2017. Going Public: A Guide for Social Scientists (with Jessie Daniels), University of Chicago Press, 2017. Reluctant Witnesses: Survivors, Their Children, and the Rise of Holocaust Consciousness, Oxford University Press, 2014. PROSE Award in Sociology and Social Work, Honorable Mention. Shameless: Sexual Dissidence in American Culture, New York University Press, 2006. A. Stein - 2 January 19, 2018 Sexuality and Gender (Christine Williams, co-editor), Blackwell, 2002. The Stranger Next Door: The Story of a Small Community’s Battle Over Sex, Faith, and Civil Rights, Beacon Press, 2001. Ruth Benedict Award, American Anthropological Association. Honor Award, American Library Association. Gustavus Myers Human Rights Book Award, Honorable Mention. Sex and Sensibility: Stories of a Lesbian Generation, University of California Press, 1997. Excerpted in 10 volumes in US, UK, Germany. -

South East Coast

NHS South East Coast New MPs ‐ May 2010 Please note: much of the information in the following biographies has been taken from the websites of the MPs and their political parties. NHS BRIGHTON AND HOVE Mike Weatherley ‐ Hove (Cons) Caroline Lucas ‐ Brighton Pavillion (Green) Leader of the Green Party of England and Qualified as a Chartered Management Wales. Previously Green Party Member Accountant and Chartered Marketeer. of the European Parliament for the South From 1994 to 2000 was part owner of a East of England region. company called Cash Based in She was a member of the European Newhaven. From 2000 to 2005 was Parliament’s Environment, Public Health Financial Controller for Pete Waterman. and Food Safety Committee. Most recently Vice President for Finance and Administration (Europe) for the Has worked for a major UK development world’s largest non-theatrical film licensing agency providing research and policy company. analysis on trade, development and environment issues. Has held various Previously a Borough Councillor in positions in the Green Party since joining in 1986 and is an Crawley. acknowledged expert on climate change, international trade and Has run the London Marathon for the Round Table Children’s Wish peace issues. Foundation and most recently last year completed the London to Vice President of the RSPCA, the Stop the War Coalition, Campaign Brighton bike ride for the British Heart Foundation. Has also Against Climate Change, Railfuture and Environmental Protection completed a charity bike ride for the music therapy provider Nordoff UK. Member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament National Robbins. Council and a Director of the International Forum on Globalization.