'New' Cello Concertos by Nicola Porpora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venice in Mexico

Venice in Mexico dda25091 dda25091 Baroque Concertos by Facco andVivaldi CD duration: 60.34 Total ©2010 Diversions LLC www.divineartrecords.com www.divine-art.co.uk Brandon, VT (USA) and Doddington, UK Divine Art Record Company, Venice in Mexico : Concertos by Facco and Vivaldi in Mexico : Concertos by Facco Venice Giacomo Facco (1676-1753) Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Mexican Baroque Orchestra : Miguel Lawrence Concerto in E minor, “Pensieri Adriarmonici” Concerto in C major for sopranino recorder, for violin, strings and basso continuo, Op. 1 No. 1 strings and basso continuo, RV.443 1. Allegro [3.25] 2. Adagio [2.27] 3. Allegro [2.48] 13. Allegro [3.31] 14. Largo [3.33] 9. Allegro molto [2.52] Concerto in A major, “Pensieri Adriarmonici” Concerto in D minor for strings and basso continuo, RV.127 for violin, strings and basso continuo, Op. 1 No. 5 16. Allegro [1.36] 17. Largo [0.58] 18. Allegro [1.12] ℗ 4. Allegro [2.56] 5. Grave [3.03] 6. Allegro [2.08] 2010 R. G. de Canales Concerto in C major for psaltery, strings and basso continuo, RV.425 Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) 19. Allegro [3.06] 20. Largo [2.52] 21. Allegro [2.32] Concerto in D major, for strings and basso continuo, RV.121 7. Allegro molto [2.14] 8. Adagio [1.22] 9. Allegro [1.46] Concerto in A minor for sopranino recorder, strings and basso continuo, RV.445 Concerto in A minor “L'estro Armonico”. 22. Allegro [4.17] 23. Largo [2.01] 24. Allegro [3.29] for violin, strings and basso continuo, Op. -

Press Caffarelli

Caffarelli pt3 VOIX-DES-ARTS.COM, 21_09_2013 http://www.voix-des-arts.com/2013/09/cd-review-arias-for-caffarelli-franco.html 21 September 2013 CD REVIEW: ARIAS FOR CAFFARELLI (Franco Fagioli, countertenor; Naïve V 5333) PASQUALE CAFARO (circa 1716 – 1787) JOHANN ADOLF HASSE (1699 – 1783), LEONARDO LEO (1694 – 1744), GENNARO MANNA (1715 – 1779), GIOVANNI BATTISTA PERGOLESI (1710 – 1736), NICOLA ANTONIO PORPORA (1686 – 1768), DOMENICO SARRO (1679 – 1744), and LEONARDO VINCI (1690 – 1730): Arias for Caffarelli—Franco Fagioli, countertenor; Il Pomo d’Oro; Riccardo Minasi [Recorded at the Villa San Fermo, Convento dei Pavoniani, Lonigo, Vicenza, Italy, 25 August – 3 September 2012; Naïve V 5333; 1CD, 78:31; Available from Amazon, fnac, JPC, and all major music retailers] If contemporary accounts of his demeanor can be trusted, Gaetano Majorano—born in 1710 in Bitonto in the Puglia region of Italy and better known to history as Caffarelli—could have given the most arrogant among the opera singers of the 21st Century pointers on enhancing their self-appreciation. Unlike many of his 18th-Century rivals, Caffarelli enjoyed a certain level of privilege, his boyhood musical studies financed by the profits of two vineyards devoted to his tuition by his grandmother. Perhaps most remarkable, especially in comparison with other celebrated castrati who invented elaborate tales of childhood illnesses and unfortunate encounters with unfriendly animals to account for their ‘altered’ states, is the fact that, having been sufficiently impressed by the quality of his puerile voice or convinced thereof by the praise of his tutors, Caffarelli volunteered himself for castration. It is suggested that his most influential teacher, Porpora, with whom Farinelli also studied, was put off by Caffarelli’s arrogance but regarded him as the most talented of his pupils, reputedly having pronounced the castrato the greatest singer in Europe—a sentiment legitimately expressive of Porpora’s esteem for Caffarelli, perhaps, and surely a fine advertisement for his own services as composer and teacher. -

On the Question of the Baroque Instrumental Concerto Typology

Musica Iagellonica 2012 ISSN 1233-9679 Piotr WILK (Kraków) On the question of the Baroque instrumental concerto typology A concerto was one of the most important genres of instrumental music in the Baroque period. The composers who contributed to the development of this musical genre have significantly influenced the shape of the orchestral tex- ture and created a model of the relationship between a soloist and an orchestra, which is still in use today. In terms of its form and style, the Baroque concerto is much more varied than a concerto in any other period in the music history. This diversity and ingenious approaches are causing many challenges that the researches of the genre are bound to face. In this article, I will attempt to re- view existing classifications of the Baroque concerto, and introduce my own typology, which I believe, will facilitate more accurate and clearer description of the content of historical sources. When thinking of the Baroque concerto today, usually three types of genre come to mind: solo concerto, concerto grosso and orchestral concerto. Such classification was first introduced by Manfred Bukofzer in his definitive monograph Music in the Baroque Era. 1 While agreeing with Arnold Schering’s pioneering typology where the author identifies solo concerto, concerto grosso and sinfonia-concerto in the Baroque, Bukofzer notes that the last term is mis- 1 M. Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, New York 1947: 318– –319. 83 Piotr Wilk leading, and that for works where a soloist is not called for, the term ‘orchestral concerto’ should rather be used. -

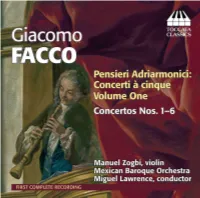

Toccata Classics TOCC0202 Notes

P GIACOMO FACCO: A VENETIAN MUSICIAN AHEAD OF HIS TIME by Betty Luisa Zanolli Fabila Facco is the composer whom I most admire: not only was he the last paladin of the pre-Classical, he looked upon the threshold of 1770 and didn’t perceive the ‘Baroque’ that encircled it. He projected himself towards a future unknown to him and which, a century after, was to be called nineteenth-century Romanticism. His ‘adagios’ and cantatas are the proof. Uberto Zanolli1 Giacomo Facco (1676–1753) is a missing link in the history of music, a musician whose work had to wait 250 years to be rescued from oblivion. This is the story. At the beginning of the 1960s Gonzalo Obregón, curator of the Archive of the Vizcainas College in Mexico City, was organising a cupboard in the compound when suddenly he was hit by a package falling from one of the shelves. It was material he had never seen before, something not included in the catalogue of documents in the College, and completely different in nature from the other materials contained in the Archive: a set of ten little books bound in leather, which contained the parts of a musical work, the Pensieri Adriarmonici o vero Concerti a cinque, Tre Violini, Alto Viola, Violoncello e Basso per il Cembalo, Op. 1 of Giacomo Facco. Obregón’s interest was piqued in knowing who this composer was and why his works were in the Archive. He went to a friend, Luis Vargas y Vargas, a doctor of radiology by profession and an amateur of music and painting, but he had no idea who Facco might have been, either. -

Arias for Farinelli

4 Tracklisting NICOLA PORPORA 7 A Master and his Pupil 1686-1768 Philippe Jaroussky Arias for Farinelli 9 Un maître et son élève Philippe Jaroussky PHILIPPE 11 Schüler und Lehrer JAROUSSKY Philippe Jaroussky countertenor 17 Sung texts CECILIA 32 The Angel and the High Priest BARTOLI Frédéric Delaméa mezzo-soprano 54 L’Ange et le patriarche Frédéric Delaméa VENICE BAROQUE ORCHESTRA 79 Der Engel und der Patriarch ANDREA Frédéric Delaméa MARCON 2 3 Nicola Antonio Porpora Unknown artist Carlo Broschi, called Farinelli Bartolomeo Nazzari, Venice 1734 5 Philippe Jaroussky C Marc Ribes Erato/Warner Classics Cecilia Bartoli C Uli Weber/Decca Classics 6 A MASTER AND HIS PUPIL Philippe Jaroussky Over all the time I have been singing I have been somewhat hesitant about tackling the repertoire of the legendary Farinelli. Instead, I have preferred to turn the spotlight on the careers of other castrati who are less well known to the general public, as I did for Carestini a few years ago. Since then, having had the opportunity to give concert performances of arias written for Farinelli, I found that they suited me far better than I could have imagined – particu lar ly those written by Nicola Porpora (1686-1768), known in his time not only as a composer, but also as one of the greatest singing teachers. I soon became interested in the master-pupil relationship that could have existed between Porpora and Farinelli. Despite the lack of historical sources, we can presume that Farinelli was still a child when he first met Porpora, and that the composer’s views had a strong bearing on the decision to castrate the young prodigy. -

The Double Keyboard Concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

The double keyboard concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Waterman, Muriel Moore, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 18:28:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318085 THE DOUBLE KEYBOARD CONCERTOS OF CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH by Muriel Moore Waterman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: JAMES R. -

Symphony 04.22.14

College of Fine Arts presents the UNLV Symphony Orchestra Taras Krysa, music director and conductor Micah Holt, trumpet Erin Vander Wyst, clarinet Jeremy Russo, cello PROGRAM Oskar Böhme Concerto in F Minor (1870–1938) Allegro Moderato Adagio religioso… Allegretto Rondo (Allegro scherzando) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto in A Major, K. 622 (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Rondo: Allegro Edward Elgar Cello Concerto, Op. 85 (1857–1934) Adagio Lento Adagio Allegro Tuesday, April 22, 2014 7:30 p.m. Artemus W. Ham Concert Hall Performing Arts Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas PROGRAM NOTES The Concerto in F minor Composed 1899 Instrumentation solo trumpet, flute, oboe, two clarinets, bassoon, four horns, trumpet, three trombones, timpani, and strings. Oskar Bohme was a trumpet player and composer who began his career in Germany during the late 1800’s. After playing in small orchestras around Germany he moved to St. Petersburg to become a cornetist for the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra. Bohme composed and published is Trumpet Concerto in E Minor in 1899 while living in St. Petersburg. History caught up with Oskar Bohme in 1934 when he was exiled to Orenburg during Stalin’s Great Terror. It is known that Bohme taught at a music school in the Ural Mountain region for a time, however, the exact time and circumstances of Bohme’s death are unknown. Bohme’s Concerto in F Minor is distinguished because it is the only known concerto written for trumpet during the Romantic period. The concerto was originally written in the key of E minor and played on an A trumpet. -

MUSIC in the BAROQUE 12 13 14 15

From Chapter 5 (Baroque) MUSIC in the BAROQUE (c1600-1750) 1600 1650 1700 1720 1750 VIVALDI PURCELL The Four Seasons Featured Dido and Aeneas (concerto) MONTEVERDI HANDEL COMPOSERS L'Orfeo (opera) and Messiah (opera) (oratorio) WORKS CORELLI Trio Sonatas J.S. BACH Cantata No. 140 "Little" Fugue in G minor Other Basso Continuo Rise of Instrumental Music Concepts Aria Violin family developed in Italy; Recitative Orchestra begins to develop BAROQUE VOCAL GENRES BAROQUE INSTRUMENTAL GENRES Secular CONCERTO Important OPERA (Solo Concerto & Concerto Grosso) GENRES Sacred SONATA ORATORIO (Trio Sonata) CANTATA SUITE MASS and MOTET (Keyboard Suite & Orchestral Suite) MULTI-MOVEMENT Forms based on opposition Contrapuntal Forms FORMS DESIGNS RITORNELLO CANON and FUGUE based on opposition BINARY STYLE The Baroque style is characterized by an intense interest in DRAMATIC CONTRAST TRAITS and expression, greater COUNTRAPUNTAL complexity, and the RISE OF INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC. Forms Commonly Used in Baroque Music • Binary Form: A vs B • Ritornello Form: TUTTI • SOLO • TUTTI • SOLO • TUTTI (etc) Opera "Tu sei morta" from L'Orfeo Trio Sonata Trio Sonata in D major, Op. 3, No. 2 1607 by Claudio MONTEVERDI (1567–1643) Music Guide 1689 by Arcangelo CORELLI (1653–1713) Music Guide Monteverdi—the first great composer of the TEXT/TRANSLATION: A diagram of the basic imitative texture of the 4th movement: Baroque, is primarily known for his early opera 12 14 (canonic imitation) L'Orfeo. This work is based on the tragic Greek myth Tu sei morta, sé morta mia vita, Violin 1 ed io respiro; of Orpheus—a mortal shepherd with a god-like singing (etc.) Tu sé da me partita, sé da me partita Violin 2 voice. -

Opera Olimpiade

OPERA OLIMPIADE Pietro Metastasio’s L’Olimpiade, presented in concert with music penned by sixteen of the Olympian composers of the 18th century VENICE BAROQUE ORCHESTRA Andrea Marcon, conductor Romina Basso Megacle Franziska Gottwald Licida Karina Gauvin Argene Ruth Rosique Aristea Carlo Allemano Clistene Nicholas Spanos Aminta Semi-staged by Nicolas Musin SUMMARY Although the Olympic games are indelibly linked with Greece, Italy was progenitor of the Olympic operas, spawning a musical legacy that continues to resound in opera houses and concert halls today. Soon after 1733, when the great Roman poet Pietro Metastasio witnessed the premiere of his libretto L’Olimpiade in Vienna, a procession of more than 50 composers began to set to music this tale of friendship, loyalty and passion. In the course of the 18th century, theaters across Europe commissioned operas from the Olympian composers of the day, and performances were acclaimed in the royal courts and public opera houses from Rome to Moscow, from Prague to London. Pieto Metastasio In counterpoint to the 2012 Olympic games, Opera Olimpiade has been created to explore and celebrate the diversity of musical expression inspired by this story of the ancient games. Research in Europe and the United States yielded L’Olimpiade manuscripts by many composers, providing the opportunity to extract the finest arias and present Metastasio’s drama through an array of great musical minds of the century. Andrea Marcon will conduct the Venice Baroque Orchestra and a cast of six virtuosi singers—dare we say of Olympic quality—in concert performances of the complete libretto, a succession of 25 spectacular arias and choruses set to music by 16 Title page of David Perez’s L’Olimpiade, premiered in Lisbon in 1753 composers: Caldara, Vivaldi, Pergolesi, Leo, Galuppi, Perez, Hasse, Traetta, Jommelli, Piccinni, Gassmann, Mysliveek, Sarti, Cherubini, Cimarosa, and Paisiello. -

Going for a Song

FESTIVALS GOING FOR A SONG The Brighton Early Music Festival 2012 celebrates its 10th birthday in 2012. Known for its lively and inspiring programming, this year’s highlights include its most spectacular production yet: ‘The 1589 Florentine Intermedi’. Organisers promise ‘a thrilling experience with all sorts of surprises.’ For more information, see http://www.bremf.org.uk Photo: ©BREMF Cambridge Early Music Italian Festival 28-30 September Italy was the source of many of the musical innovations of the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and CEM’s Festival of Italian Music explores this fertile period, welcoming some of Europe’s foremost performers of these genres. It was exactly 300 years ago that Vivaldi published his ground-breaking set of 12 Julian Perkins, one of the leaders of the new concertos, L’Estro Armonico generation of virtuoso keyboard players in the (The Birth of Harmony), which UK, will play Frescobaldi and the Scarlattis – La Serenissima (pictured), the father and son – in a lunchtime clavichord Vivaldi orchestra par excellence, recital on 30 September. will be playing with terrific verve and style. www.CambridgeEarlyMusic.org tel. 01223 847330 Come and Play! Lorraine Liyanage, who runs a piano school in south London, has always been intrigued by the harpsichord. Inspired by a colleague to introduce the instrument to her young students in her home, she tells how the experiment has gone from strength to strength – and led to the purchase of a spinet that fits obligingly in her bay window… 10 ast Summer, I received an email from Petra Hajduchova, a local musician enquiring about the possibility of teaching at my piano school. -

Cechy Weneckie W Pensieri Adriarmonici Giacoma Facca*

10.2478/v10075-012-0014-6 ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS MARIAE CURIE-SKã ODOWSKA LUBLIN – POLONIA VOL. IX, 2 SECTIO L 2011 Instytut Muzykologii UJ PIOTR WILK Cechy weneckie w Pensieri adriarmonici Giacoma Facca* Venetian Features in Giacomo Facco’s Pensieri adriarmonici W roku 1716 i 1719 w amsterdamskiej o¿ cynie Rogera ukazaáy siĊ kolejno dwie ksiĊgi koncertów fantazyjnie zatytuáowanych Pensieri adriarmonici. Choü ich autor – Giacomo Facco (1676-1753) – najbardziej wpáywowy Wáoch na Póá- wyspie Iberyjskim przed przybyciem Farinellego, znany byá od dawna z haseá w muzycznych leksykonach Walthera, Fétisa, Eitnera i Riemanna1, jego twór- czoĞü instrumentalna wciąĪ pozostaje bliĪej niezbadana2. Urodziá siĊ w Marsango * Praca naukowa ¿ nansowana ze Ğrodków MNiSW na naukĊ w latach 2007-2010 jako projekt badawczy. 1 Zob. J. G. Walther, Musicalisches Lexicon oder Musicalische Bibliothek, Lipsk 1732, s. 238; F. J. Fétis, Biographie universelle des musiciens et bibliographie générale de la musique, wyd. 2 popr., t. 3, Bruksela 1866, s. 176; R. Eitner, Biogra¿ sch-Bibliographisches Quellen-Lexikon der Musiker und Musikgelehrten, wyd. 2 popr., t. 3, Graz 1959, s. 379-380; H. Riemann, Riemann Musik Lexikon, t. 2, Moguncja 1959, s. 484. Hasáa Facco brakuje w Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, red. F. Blume, Kassel 1949-79 (pierwsza edycja). 2 Nie znajdziemy Īadnej wzmianki na temat Facca w najwaĪniejszych monogra¿ ach dotyczących koncertu w XVIII w. Por. A. Hutchings, The Baroque Concerto, Londyn 1961; Ch. White, From Vivaldi to Viotti. A history of the early classical violin concerto, Filadel¿ a 1992, S. McVeigh, J. Hirshberg, The Italian Solo Concerto, 1700-1760. Rhetorical Strategies and Style History, Woodbridge 2004; The Cambridge Companion to the Concerto, red. -

Neue Bach-Ausgabe of 1969, 152 – 32 Pages Fewer Than Bärenreiter

Early Music Review EDITIONS OF MUSIC have been rejected. What Bach is concerned with is the total length, not so much as individual pieces but groups J. S. Bach Complete Organ Works vol.8: of pieces (e.g. the first 24 preludes and fugues) and the idea is most lengthily shown in the B-minor Mass. The Organ Chorales of the Leipzig Manuscript “18” is a dubious choice because nos. 16-18 were written Edited by Jean-Claude Zehnder. after the composer’s death. I wonder whether the first Breitkopf Härtel (EB8808), 2015. & piece in the collection, Fantasia super Komm, Heiliger 183pp + CD containing musical texts, commentary & Geist, was expanded from 48 to 105 bars as the quickest synoptical depiction. €26.80. way to complete the round number. The total bars of any individual chorale is only relevant to the total, and the bought the Bärenreiter equivalent (vol. 2) back in 1961, only round sum covers BWV 651-665. It does seem an three years after it was published. Bach evidently was odd concept and I can’t take it seriously – the 1200 bars I expecting to produce a larger work than the six Organ do not help guess how to fit such a length into CD discs. Sonatas, assembled around 1730; he then waited a decade But that Bach wrote “The 15” rather than “The 18” could, before moving on around 1740, using the same paper. He even without a total bar count, suggest that BWV 666-668 copied 15 pieces, then had a break. BWV666 and 667 were should be left as an appendix.