585 on the Whole, I Highly Recommend This Book Because It Provides A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metro Railway Kolkata Presentation for Advisory Board of Metro Railways on 29.6.2012

METRO RAILWAY KOLKATA PRESENTATION FOR ADVISORY BOARD OF METRO RAILWAYS ON 29.6.2012 J.K. Verma Chief Engineer 8/1/2012 1 Initial Survey for MTP by French Metro in 1949. Dum Dum – Tollygunge RTS project sanctioned in June, 1972. Foundation stone laid by Smt. Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India on December 29, 1972. First train rolled out from Esplanade to Bhawanipur (4 km) on 24th October, 1984. Total corridor under operation: 25.1 km Total extension projects under execution: 89 km. June 29, 2012 2 June 29, 2012 3 SEORAPFULI BARRACKPUR 12.5KM SHRIRAMPUR Metro Projects In Kolkata BARRACKPUR TITAGARH TITAGARH 10.0KM BARASAT KHARDAH (UP 17.88Km) KHARDAH 8.0KM (DN 18.13Km) RISHRA NOAPARA- BARASAT VIA HRIDAYPUR PANIHATI AIRPORT (UP 15.80Km) (DN 16.05Km)BARASAT 6.0KM SODEPUR PROP. NOAPARA- BARASAT KONNAGAR METROMADHYAMGRAM EXTN. AGARPARA (UP 13.35Km) GOBRA 4.5KM (DN 13.60Km) NEW BARRACKPUR HIND MOTOR AGARPARA KAMARHATI BISARPARA NEW BARRACKPUR (UP 10.75Km) 2.5KM (DN 11.00Km) DANKUNI UTTARPARA BARANAGAR BIRATI (UP 7.75Km) PROP.BARANAGAR-BARRACKPORE (DN 8.00Km) BELGHARIA BARRACKPORE/ BELA NAGAR BIRATI DAKSHINESWAR (2.0Km EX.BARANAGAR) BALLY BARANAGAR (0.0Km)(5.2Km EX.DUM DUM) SHANTI NAGAR BIMAN BANDAR 4.55KM (UP 6.15Km) BALLY GHAT RAMKRISHNA PALLI (DN 6.4Km) RAJCHANDRAPUR DAKSHINESWAR 2.5KM DAKSHINESWAR BARANAGAR RD. NOAPARA DAKSHINESWAR - DURGA NAGAR AIRPORT BALLY HALT NOAPARA (0.0Km) (2.09Km EX.DMI) HALDIRAM BARANAGAR BELUR JESSOR RD DUM DUM 5.0KM DUM DUM CANT. CANT 2.60KM NEW TOWN DUM DUM LILUAH KAVI SUBHAS- DUMDUM DUM DUM ROAD CONVENTION CENTER DUM DUM DUM DUM - BELGACHIA KOLKATA DASNAGAR TIKIAPARA AIRPORT BARANAGAR HOWRAH SHYAM BAZAR RAJARHAT RAMRAJATALA SHOBHABAZAR Maidan BIDHAN NAGAR RD. -

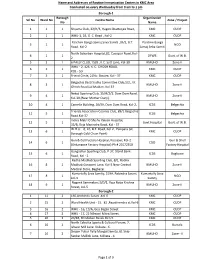

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

An Urban River on a Gasping State: Dilemma on Priority of Science, Conscience and Policy

An urban river on a gasping state: Dilemma on priority of science, conscience and policy Manisha Deb Sarkar Former Associate Professor Department of Geography Women’s Christian College University of Calcutta 6, Greek Church Row Kolkata - 700026 SKYLINE OF KOLKATA METROPOLIS KOLKATA: The metropolis ‘Adi Ganga: the urban river • Human settlements next to rivers are the most favoured sites of habitation. • KOLKATA selected to settle on the eastern bank of Hughli River – & •‘ADI GANGA’, a branched out tributary from Hughli River, a tidal river, favoured to flow across the southern part of Kolkata. Kolkata – View from River Hughli 1788 ADI GANGA Present Transport Network System of KOLKATA Adi Ganga: The Physical Environment & Human Activities on it: PAST & PRESNT Adi Ganga oce upo a tie..... (British period) a artists ipressio Charles Doyle (artist) ‘Adi Ganga’- The heritage river at Kalighat - 1860 Width of the river at this point of time Adi Ganga At Kalighat – 1865 source: Bourne & Shepard Photograph of Tolly's Nullah or Adi Ganga near Kalighat from 'Views of Calcutta and Barrackpore' taken by Samuel Bourne in the 1860s. The south-eastern Calcutta suburbs of Alipore and Kalighat were connected by bridges constructed over Tolly's Nullah. Source: British Library ’ADI Ganga’ & Kalighat Temple – an artists ipressio in -1887 PAST Human Activities on it: 1944 • Transport • Trade • Bathing • Daily Domestic Works • Performance of Religious Rituals Present Physical Scenario of Adi Ganga (To discern the extant physical condition and spatial scales) Time Progresses – Adi Ganga Transforms Laws of Physical Science Tidal water flow in the river is responsible for heavy siltation in the river bed. -

The Hooghly River a Sacred and Secular Waterway

Water and Asia The Hooghly River A Sacred and Secular Waterway By Robert Ivermee (Above) Dakshineswar Kali Temple near Kolkata, on the (Left) Detail from The Descent of the Ganga, life-size carved eastern bank of the Hooghly River. Source: Wikimedia Commons, rock relief at Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu, India. Source: by Asis K. Chatt, at https://tinyurl.com/y9e87l6u. Wikimedia Commons, by Ssriram mt, at https://tinyurl.com/y8jspxmp. he Hooghly weaves through the Indi- Hooghly was venerated as the Ganges’s original an state of West Bengal from the Gan- and most sacred route. Its alternative name— ges, its parent river, to the sea. At just the Bhagirathi—evokes its divine origin and the T460 kilometers (approximately 286 miles), its earthly ruler responsible for its descent. Hindus length is modest in comparison with great from across India established temples on the Asian rivers like the Yangtze in China or the river’s banks, often at its confluence with oth- Ganges itself. Nevertheless, through history, er waterways, and used the river water in their the Hooghly has been a waterway of tremen- ceremonies. Many of the temples became fa- dous sacred and secular significance. mous pilgrimage sites. Until the seventeenth century, when the From prehistoric times, the Hooghly at- main course of the Ganges shifted decisively tracted people for secular as well as sacred eastward, the Hooghly was the major channel reasons. The lands on both sides of the river through which the Ganges entered the Bay of were extremely fertile. Archaeological evi- Bengal. From its source in the high Himalayas, dence confirms that rice farming communi- the Ganges flowed in a broadly southeasterly ties, probably from the Himalayas and Indian direction across the Indian plains before de- The Hooghly was venerated plains, first settled there some 3,000 years ago. -

Urban Ethnic Space: a Discourse on Chinese Community in Kolkata, West Bengal

Indian Journal of Spatial Science Spring Issue, 10 (1) 2019 pp. 25 - 31 Indian Journal of Spatial Science Peer Reviewed and UGC Approved (Sl No. 7617) EISSN: 2249 - 4316 homepage: www.indiansss.org ISSN: 2249 - 3921 Urban Ethnic Space: A Discourse on Chinese Community in Kolkata, West Bengal Sudipto Kumar Goswami Research Scholar, Department of Geography, Visva-Bharati, India Dr.Uma Sankar Malik Professor of Geography, Department of Geography, Visva-Bharati, India Article Info Abstract _____________ ___________________________________________________________ Article History The modern urban societies are pluralistic in nature, as cities are the destination of immigration of the ethnic diaspora from national and international sources. All ethnic groups set a cultural distinction Received on: from another group which can make them unlike from the other groups. Every culture is filled with 20 August 2018 traditions, values, and norms that can be traced back over generations. The main focus of this study is to Accepted inRevised Form on : identify the Chinese community with their history, social status factor, changing pattern of Social group 31 December, 2018 interaction, value orientation, language and communications, family life process, beliefs and practices, AvailableOnline on and from : religion, art and expressive forms, diet or food, recreation and clothing with the spatial and ecological 21 March, 2019 frame in mind. So, there is nothing innate about ethnicity, ethnic differences are wholly learned through __________________ the process of socialization where people assimilate with the lifestyles, norms, beliefs of their Key Words communities. The Chinese community of Kolkata which group possesses a clearly defined spatial segmentation in the city. They have established unique modes of identity in landscape, culture, Ethnicity economic and inter-societal relations. -

CC-12:HISTORY of INDIA(1750S-1857) II.EXPANSION and CONSOLIDATION of COLONIAL POWER

CC-12:HISTORY OF INDIA(1750s-1857) II.EXPANSION AND CONSOLIDATION OF COLONIAL POWER: (A) MERCANTILISM,FOREIGN TRADE AND EARLY FORMS OF EXTRACTION FROM BENGAL The coming of the Europeans to the Indian subcontinent was an event of great significance as it ultimately led to revolutionary changes in its destiny in the future. Europe’s interest in India goes back to the ancient times when lucrative trade was carried on between India and Europe. India was rich in terms of spices, textile and other oriental products which had huge demand in the large consumer markets in the west. Since the ancient time till the medieval period, spices formed an important part of European trade with India. Pepper, ginger, chillies, cinnamon and cloves were carried to Europe where they fetched high prices. Indian silk, fine Muslin and Indian cotton too were much in demand among rich European families. Pearls and other precious stone also found high demand among the European elites. Trade was conducted both by sea and by land. While the sea routes opened from the ports of the western coast of India and went westward through the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea to Alexandria and Constantinople, Indian trade goods found their way across the Mediterranean to the commercials hubs of Venice and Genoa, from where they were then dispersed throughout the main cities of Europe. The old trading routes between the east and the west came under Turkish control after the Ottoman conquest of Asia Minor and the capture of Constantinople in1453.The merchants of Venice and Genoa monopolised the trade between Europe and Asia and refused to let the new nation states of Western Europe, particularly Spain and Portugal, have any share in the trade through these old routes. -

Landscaping India: from Colony to Postcolony

Syracuse University SURFACE English - Dissertations College of Arts and Sciences 8-2013 Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony Sandeep Banerjee Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Geography Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Sandeep, "Landscaping India: From Colony to Postcolony" (2013). English - Dissertations. 65. https://surface.syr.edu/eng_etd/65 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in English - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT Landscaping India investigates the use of landscapes in colonial and anti-colonial representations of India from the mid-nineteenth to the early-twentieth centuries. It examines literary and cultural texts in addition to, and along with, “non-literary” documents such as departmental and census reports published by the British Indian government, popular geography texts and text-books, travel guides, private journals, and newspaper reportage to develop a wider interpretative context for literary and cultural analysis of colonialism in South Asia. Drawing of materialist theorizations of “landscape” developed in the disciplines of geography, literary and cultural studies, and art history, Landscaping India examines the colonial landscape as a product of colonial hegemony, as well as a process of constructing, maintaining and challenging it. In so doing, it illuminates the conditions of possibility for, and the historico-geographical processes that structure, the production of the Indian nation. -

Download Book

"We do not to aspire be historians, we simply profess to our readers lay before some curious reminiscences illustrating the manners and customs of the people (both Britons and Indians) during the rule of the East India Company." @h£ iooi #ld Jap €f Being Curious Reminiscences During the Rule of the East India Company From 1600 to 1858 Compiled from newspapers and other publications By W. H. CAREY QUINS BOOK COMPANY 62A, Ahiritola Street, Calcutta-5 First Published : 1882 : 1964 New Quins abridged edition Copyright Reserved Edited by AmARENDRA NaTH MOOKERJI 113^tvS4 Price - Rs. 15.00 . 25=^. DISTRIBUTORS DAS GUPTA & CO. PRIVATE LTD. 54-3, College Street, Calcutta-12. Published by Sri A. K. Dey for Quins Book Co., 62A, Ahiritola at Express Street, Calcutta-5 and Printed by Sri J. N. Dey the Printers Private Ltd., 20-A, Gour Laha Street, Calcutta-6. /n Memory of The Departed Jawans PREFACE The contents of the following pages are the result of files of old researches of sexeral years, through newspapers and hundreds of volumes of scarce works on India. Some of the authorities we have acknowledged in the progress of to we have been indebted for in- the work ; others, which to such as formation we shall here enumerate ; apologizing : — we may have unintentionally omitted Selections from the Calcutta Gazettes ; Calcutta Review ; Travels Selec- Orlich's Jacquemont's ; Mackintosh's ; Long's other Calcutta ; tions ; Calcutta Gazettes and papers Kaye's Malleson's Civil Administration ; Wheeler's Early Records ; Recreations; East India United Service Journal; Asiatic Lewis's Researches and Asiatic Journal ; Knight's Calcutta; India. -

Kalighat for 21St Century

CONCEPT SCHEME KALIGHAT FOR 21ST CENTURY INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE BOSTON PLEDGE, USA AND GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL PRESENTATION BY MODULAR CONSULTANTS (P) Ltd. Prime Consultant MCPL IFSD SCOPE OF WORK Census & public enlightenment Renovation programme for existing occupiers / services provides in the redevelopment area Restructure of vehicular traffic Open / covered walk-track to Kali Temple Dredging & embankment protection of Adi Ganga upto Sluise Gate and connect the River Cruise from Sahara’s proposed Embarkation Jetty near Outram Ghat Construction of Foot Bridge over Adi Ganga Reconstruction of Adi Ganga Bathing Ghat Beautification of existing façade Rejuvenating the Craftsmanship of Patuas Travellers’ / Tourists’ Amenities Modernization of Kali Temple Water supply system including treatment plant Sewerage Disposal Solid waste management system Environment Management Plan Electricity supply and distribution system MCPL IFSD STATEMENT OF INTENT 1. Clean existing scum, filth and slummy environment of the temple area. 2. Remove and rehabilitate existing street vendors and street stalls. 3. Remove and rehabilitate stalls directly attached to the inside and outside of the temple compound walls and areas. Temple footprint should be free of any obstruction. Fresh paint on temple structure needed. 4. Incorporate spiritual AXES, NUMBERS and DIAGRAMS in new configuration of design elements brought into the proposed scheme. 5. Use pure forms and forms reminiscent of the main temple roof in new design elements as much as possible. 6. Create a SENSE OF PILGRIMAGE in the area. 7. Use Kali Temple Road as the MAIN AXIS to approach the temple. 8. Build FOUR gates on four perimeter roads of the ward. -

Reclaiming the Indigenous Style of Kalighat Paintings Lauren M. Slaughter

Reclaiming the Indigenous Style of Kalighat Paintings Lauren M. Slaughter This essay re-examines the nature of Kalighat painting, a painting style which emerged in India in the early nineteenth century and ended not long after the early twentieth century. Stemming from traditional Indian scroll painting, Kalighat paintings were created by patuas who migrated from Bengal villages into Calcutta and set up their “shop- studios” around the Kalighat temple (Guha-Thakurta, Making 17; Jain 9). Patuas represent a caste of traveling scroll-painters and performers; the earliest mention of this artisan caste appears in Brahma Vaivarta Purana, a thirteenth-century Sanskrit text (Chatterjee 50). As a result of W. G. Archer’s 1953 Bazaar Paintings of Calcutta: The Style of Kalighat, the general consensus of scholarly literature suggests that Kalighat painting reflects a western influence on thepatua artists. In line with the work of Tapati Guha-Thakurta and B.N. Mukherjee, however, I want to argue that there is not enough evidence to support the claim that this style was shaped by contact with western painting; instead I will argue that it was essentially indigenous in style, medium, and subject matter. Because stating that Kalighat paintings are British-derived diminishes their value and robs these works of their true substance, my aim is to substantiate their indigenous origins and, in so doing, explain how this re-interpretation provides new ways of understanding the innovative style of Kalighat patuas. Chrestomathy: Annual Review of Undergraduate Research, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, School of Languages, Cultures, and World Affairs, College of Charleston Volume 11 (2012): 242-258 © 2012 by the College of Charleston, Charleston SC 29424, USA. -

Bharath Market Research Consultancy

+91-9562512065 Bharath Market Research Consultancy https://www.indiamart.com/bharath-marketresearch-consultancy/ Kolkata formerly known as Calcutta is a city of many hues, recognized by many as the cultural capital of India, known to others as the city of palaces and to yet others as the city of joy it is difficult to capture its diversity. About Us Kolkata formerly known as Calcutta is a city of many hues, recognized by many as the Cultural Capital of India, known to others as the City of Palaces and to yet others as the City of Joy; it is difficult to capture its diversity as well as uniqueness within the confines of a single phrase.Located on the eastern bank of the river Hooghly, Calcutta was established by the British in an area where the villages Kalikata, Sutanuti and Govindapur existed.These villages were part of an estate which belonged to the Mughal emperor himself and whose jagirdari was held by the Sabarna Roy Choudhury family. The rights were transferred to the East India Company in 1698 and it became the capital of British Indian in 1772.The city grew under the British and saw the emergence of a new educated urbane Babu class in the 19th century. Calcutta becomes the pioneering center of socio- cultural revolution often referred to as the Bengal Renaissance. Calcutta also became the epicenter of the Indian independence movement, especially the revolutionary stream. In 1905 Bengal was partitioned on communal grounds which resulted in widespread public agitation and the boycott of British goods (Swadeshi movement). The British moved the capital to New Delhi in 1911 in view of these developments and also the fact that Calcutta was located in the eastern fringes of India. -

JOB CHARNOCK the Founder of Calcutta

librarian Vttarpara Joykti^hmi Public Llbraif Govt. of Wat Bctjaa) JOB CHARNOCK The Founder of Calcutta (In Facts <6 Fiction) An Anthology Compiled bjt P. THANKAPPAN NAIR Distributors CALCUTTA OLD BOOK STALL 9, Shyama Charan De Street CALCUTTA-700073 7 First Published in 1977 Text Printed by Mohammed Ayub Ansari at Shahnaz Printing & Stationery Works, 2/H/16 Radha Gobindo Saha Lane, Calcutta-70001 Cover and Illustrations printed at Engineering Times Printing Press, 35 Chittaranjan Avenue Calcutta 700012 Published by E. H. Tippoo for Engineering Times Publications Private Ltd. Wachel Molla Mansion, 8 Lenin Sarani, C alcuita-700072 Price : Rs. 30 00 ' CONTENTS Preface PART I -JOB CHARNOCK - IN FACTS I. A Portrait of Job Charnock .... 1 P . Thankappan Nair 2. Job Charnock ... 60 Philip Woodruff 3 . Job Charnock 68 G. W. Forrest 4. Job Charnock Founds Calcutta .... 90 Arnold Wright 5. Portrait of Job Charnock .... 107 From Calcutta Review 1 6. Charnock and Chutianutti ... 113 J. C. Marshman 7. Charnock’s Character ... 115 W. K. Firminger 8, Governor Job Charnock .... 122 From Bengal Obituary 9. Charnock in D.N.B. ... 125 ... 131 10. Job Charnock’s Hindu Wife : A Rescued Sati Hari Charan Biswas 11. Some Historical Myths ... ... 137 Wilma! Corfield 12. W. K. Firminger’s Note on Mr. Biswas’s preceding article ... 141 13. Job Charnock’s Visit to ,Fort St. George & Baptism of his Children — • • • 143 Frank Penny Vi ( ) H Job Charnock - His Parentage and Will 151 Sir R. C. Temple 15 Job Charnock, the Founder of Calcutta, and the Armenian Controversy .... ... 164 H. W . B. Moreno 19.