G.F. Watts' Time, Death and Judgement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhodes Memorial the Immense and Brooding Spirit Still Shall Quicken and Control

FREE Please support our advertisers who make this free guide possible PLEASE TIP Cape Town EMPOWERMENT VENDORS GATEWAYGUIDES Rhodes Memorial The immense and brooding spirit still shall quicken and control. Living he was the land, and dead, his soul shall be her soul! Muizenberg Rhodes Memorial Rudyard Kipling 1 False Bay To advertise here contact Hayley Burger: 021 487 1200 • [email protected] Earl Grey, the Colonial Secretary, Rhodes did not ‘miss the bus’ as Neville Chamberlain said; he started 100 YEAR proposed a massive statue of a company, ‘The Gold Fields of South Africa Ltd’. His next move was to Cape Point ANNIVERSARY a human figure on the summit turn over all properties and interests to shareholders to run the business, 2012 of Signal Hill, overlooking Cape and in return, Rhodes and his partner, Charles Rudd, would receive Town, that would rival the statue a ‘founders share’ which was two-fifteenths of the profits. This of Christ in Rio de Janeiro and the worked out to up to 400,000 pounds a year. The shareholders, Statue of Liberty in New York. The after a number of years, resented this arrangement - as a idea was met with horror and was result, Rhodes became a ordinary shareholder with a total squashed immediately. The figure of 1,300,000 pounds worth of shares. He also invested in was to be of Cecil John Rhodes, other profitable mining companies on the Rand. In 1890, a man of no royalty, neither hero the first disaster hit the gold industry. As the mines 2 nor saviour; so, who was this became deeper, they hit a layer of rock containing To advertise here contact Hayley Burger: man and what did he do that a pyrites which retarded the then recovery process. -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Italian Renaissance: Envisioning Aesthetic Beauty and the Past Through Images of Women

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN Carolyn Porter Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Carolyn Elizabeth Porter 2010 All Rights Reserved “DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN” A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CAROLYN ELIZABETH PORTER Master of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Furman University, 2004 Director: ERIC GARBERSON ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe a huge debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions that have helped this project along for many years. Without their generous support in the form of financial assistance, sound professional advice, and unyielding personal encouragement, completing my research would not have been possible. I have been fortunate to receive funding to undertake the years of work necessary for this project. Much of my assistance has come from Virginia Commonwealth University. I am thankful for several assistantships and travel funding from the Department of Art History, a travel grant from the School of the Arts, a Doctoral Assistantship from the School of Graduate Studies, and a Dissertation Writing Assistantship from the university. -

Case 21 2012/13: a Julia Margaret Cameron Photo Album

Case 21 2012/13: A Julia Margaret Cameron Photo Album Expert adviser’s statement Reviewing Committee Secretary’s note: Please note that any illustrations referred to have not been reproduced on the Arts Council England Website SUMMARY OF WORK Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) – (Compiler) THE "SIGNOR 1857" ALBUM, 1857 Sotheby’s Sale L12408, 12 December, 2012, Lot 65) 35 photographs by various photographers, including Cameron, Reginald Southey, Rejlander, and 2nd Earl Brownlow, all mounted individually on within an album (one leaf now loose), comprising 3 salted paper prints and 32 albumen prints, 24 images with later inscriptions in pencil by Mary Seton Watts identifying the sitters and occasionally with other notes, one inscription in ink by George Frederic Watts, a few annotations by Julia Margaret Cameron, and with further pencil inscriptions in two further hands, one providing children’s ages, the other identifying sitters, also with a later inscription on the front pastedown giving an (incorrect) summary of the content, four stubs, one page with adhesive residue where a photograph or other insertion has apparently been removed, 35 pages, plus blanks, 4to (246 x 197mm), green morocco, marbled endpapers, gilt borders and gilt stamped on upper cover “Signor.1857”. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) was one of the greatest nineteenth century artists in any medium and one of the greatest photographers that Britain has ever produced. She took her first photograph in 1864 but was actively involved with photography prior to this, compiling a number of albums. The Signor 1857 album is the earliest of eight recorded photographic albums assembled by Cameron in the period before she took up photography herself. -

Fallen Woman Or Fallen Man? Representations of Moral

XVIII Fallen Woman or Fallen Man? Representations of moral responsibility, punishment and reward in George Frederic Watts’s painting Found Drowned (1848-50) and Charles Dickens’s novel Our Mutual Friend (1864-5). SUSAN KNIGHTS This article will examine gendered representations of moral responsibility by comparing its treatment of fallen women in the above artefacts. George Frederic Watts evinces sympathy and condemnation for the plight of a drowned woman, alone bearing the punishment for her fall from prevalent societal expectations of female behaviour. Charles Dickens appears to go further in challenging the distribution of moral responsibility, inverting the stereotypic trope of the fallen woman by instead punishing a fallen man for his moral failure. Both artefacts, however, remain trapped in the dominant cultural model of the time, with its privileging of the patriarchal home as the best protector of female propriety. They thus re-enforce stereotypic inscriptions of gender. Read together as social documents, they reflect a society in transition, in which attitudes towards morality, class and gender, far from being universal and absolute, were fraught with paradox, uncertainty and ambivalence. he Victorians were much exercised by perceived essentialist gender differences, Tadvocating separate public or private spheres for men and women even as a burgeoning urban female workforce increasingly complicated strict delineations. Traditionally, women were expected to maintain the highest moral standards, but were disproportionately castigated -

19Th Century European Paintings I New York I November 7, 2018 24960

New York I November 7, 2018 New York 19th Century European Paintings European 19th Century 19th Century European Paintings I New York I November 7, 2018 24960 19th Century European Paintings New York | Wednesday 7 November 2018, at 2pm BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES ILLUSTRATIONS 580 Madison Avenue +1 (212) 644 9001 Mark Fisher, Director Front cover: Lot 53 New York, New York 10022 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax +1 (323) 436 5488 Inside front cover: Lot 26 bonhams.com [email protected] [email protected] Facing page: Lot 41 Back cover: Lot 34 PREVIEW To bid via the internet please Madalina Lazen, Director Inside back cover: Lot 21 Saturday 3 November 12-5pm visit www.bonhams.com/24960 +1 (212) 644 9108 Index ghost image: Lot 32 Sunday 4 November 12-5pm [email protected] Monday 5 November 10am-5pm Please note that telephone bids REGISTRATION Tuesday 6 November 10am-5pm must be submitted no later Rocco Rich, Specialist IMPORTANT NOTICE than 4pm on the day prior to +1 (323) 436 5410 Please note that all customers, the auction. New bidders must [email protected] SALE NUMBER: 24960 irrespective of any previous activity also provide proof of identity with Bonhams, are required to and address when submitting London complete the Bidder Registration CATALOG: $35 bids. Telephone bidding is only Charles O’Brien Form in advance of the sale. The available for lots with a low +44 (0) 20 7468 8360 form can be found at the back estimate in excess of $1000. [email protected] of every catalogue and on our website at www.bonhams.com Please contact client services Peter Rees and should be returned by email or with any bidding inquiries. -

Pre-Raphaelite List John Everett Millais, Christina Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, George Frederic Watts, Thomas Woolner

Pre-Raphaelite List John Everett Millais, Christina Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, George Frederic Watts, Thomas Woolner, Also includes: General Reference & Friends of the Pre-Raphaelites John Everett Millais English painter and illustrator Sir J. E. Millais (1829 - 1896) is credited with founding the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood along with D.G. Rossetti and William Holman Hunt in 1848. An artistic prodigy, he entered the Royal Academy at age eleven, the youngest student to enroll. He later became one of the wealthiest artists of the time. 1. Reid, J. Eadie. Sir J. E. Millais, P.R.A. London: The Walter Scott Publishing Co., Ltd, 1909. Illustrated with 20 plates and a photogravure frontispiece. Focusing on the biographical details and artworks of Millais, this book describes his involvement with the Pre-Raphaelites, portrait paintings, landscape paintings, ailments, travel, and more. Bound in full blue leather prize binding with the Watford Grammar School’s insignia in bright gilt on the front board. Red leather title label with gilt title to spine. Gilt decoration and raised bands to spine. Gilt rules to edges of boards and embossed turn-ins. Minor rubbing to hinges, spine ends, raised bands, and edges of boards. Marbled paper end pages and marbled edges. A certificate stating that this book was awarded to C.T. Sharman for drawing in July 1910 is affixed to the front pastedown. There are a few spots of foxing to the interior, else very clean. An attractive book. Appendices and Index, 193 pages. In very good condition. (#22060) $100 2. Trollope, Anthony Illustrated by, J.E. -

George Frederic WATTS (London 1817 - Compton 1904)

George Frederic WATTS (London 1817 - Compton 1904) Vesuvius Watercolour and gouache on blue-grey paper, laid down. Inscribed Naples in pencil on the verso. 72 x 145 mm. (2 7/8 x 5 3/4 in.) [sheet] The four years that Watts spent in Italy in the 1840s were crucial to his artistic development. As Barbara Bryant has noted of this period, ‘Landscape painting first engaged Watts during this time in Italy and it continued to feature in his work ever after…Travel often prompted him to turn to landscape; one visitor to his studio observed that he ‘filled his portfolios with precious memories of foreign lands’…For Watts such landscape studies provided the raw materials for his imagination.’ Artist description: One of the most famous artists of his day, George Frederic Watts followed a childhood apprenticeship in the studio of the sculptor William Behnes with studies at the Royal Academy Schools. His early years as an independent artist were largely devoted to portraiture, and among his first significant patrons was the Anglo-Greek merchant Alexander Constantine Ionides. In 1843 he travelled to Italy and spent the next four years living and working in Florence, where his first hosts were Lord and Lady Holland, and also visited Perugia, Milan, Rome and Naples. Back in London in 1847, Watts continued to paint both history subjects and portraits, and enjoyed considerable commercial success, aided by his association with a large circle of eminent and influential society patrons. In 1852 he won a commission for a fresco for the new Palace of Westminster. -

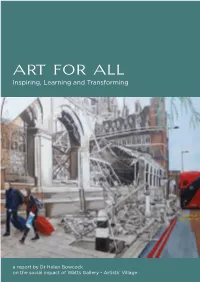

ART for ALL Inspiring, Learning and Transforming

ART FOR ALL Inspiring, Learning and Transforming a report by Dr Helen Bowcock on the social impact of Watts Gallery - Artists’ Village We selected this painting by Dena from HMP An underlying theme of this report is time Send for the cover of this report because it and the way in which the staf at Watts it is so striking and conveys messages about Gallery - Artists’ Village skilfully reconcile journeys, about time and ultimately about the requirements of a twenty-first century hope. During the many interviews conducted organisation with the ideals and legacy of during the research for this report, I have nineteenth-century philanthropy. Without observed the role that Watts Gallery - Artists’ the great gift from G F and Mary Watts and Village has played in helping diferent people the commitment of its Director and staf to on their journeys through life and in giving upholding their mission of Art for All, many them hope. But it was only after we had people would miss out on the transformative selected Dena’s painting that its significance capacity of art. So for many reasons, Dena’s as a metaphor for the Artists’ Village became painting seems a most appropriate starting apparent. point for the report, and we are grateful to her as the artist for providing it. Dena has painted the beautiful St Pancras Station in ruins but reminds us through the ‘We all journey, the building was rebuilt after contemporary street scene that it has been it was hit during World War 2; the bus is on restored to its full architectural splendour. -

WATTS Stationary

HELEN ALLINGHAM 21 NOVEMBER 2017 – 18 FEBRUARY 2018 WATTS GALLERY – ARTISTS’ VILLAGE This winter, Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village presents the UK’s first major public art gallery exhibition devoted to the artist Helen Allingham RWS (1848-1926). Allingham is one of the most familiar and well-loved of Victorian artists – in 1890 she became the first woman to be admitted to full membership of the Royal Watercolour Society and her work was highly acclaimed by leading contemporary critics, including John Ruskin. Despite this success there have been few exhibitions dedicated to her work. This exhibition will seek to reassert the reputation of Helen Allingham as a leading woman artist and as a key figure in Victorian art. Bringing together rarely seen works from private collections together with important paintings from public collections, the exhibition will demonstrate Allingham’s extraordinary talent as a watercolourist and will examine how she became one of the most successful creative women of the nineteenth century. Having moved to London aged just seventeen, Allingham trained at the Royal Female School of Art and the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. By 1870, she was pursuing a professional career as a graphic artist and children’s book illustrator, becoming the only female founding member of The Graphic, a new illustrated weekly magazine. Illuminating Allingham’s early career the exhibition will display an array of graphic works, including the illustrations to Thomas Hardy’s Far From the Madding Crowd when first published as a serial in the Cornhill Magazine. Following her marriage to the renowned Irish poet William Allingham in 1874, Allingham began to focus on working in watercolour producing vivid depictions of rural England. -

The Studio-Houses of the 'Holland Park Circle'

Visitor Factsheet 9 THE STUDIO-HOUSES OF THE ‘HOLLAND PARK CIRCLE’ When Leighton’s house was first completed in 1866, the view from his dining room was onto open parkland stretching to the north. While never entirely losing this semi-rural character, the outlook changed dramatically over the 30 years that Leighton lived here, as a unique colony of artists’ houses grew up around him. In 1875 Melbury Road was laid out across the back of the garden. Following Leighton’s example in Holland Park Road, many of the plots along it were bought by up-and-coming artists who then commissioned leading architects to design houses that combined studio space with domestic quarters for them and their families. Built on a grand scale and to the artists’ exacting requirements, these houses were investments, designed to further the reputation and standing of their occupants. Ultimately the painters and sculptors living in ‘Paradise Row’ became the backbone of the artistic establishment enjoying great wealth and fame. All bar one were made full Royal Academicians (Watts resigned following Leighton’s death), with numerous public honours and titles bestowed upon them. Although the reputation of many of these artists has faded, all but two of their houses still remain, allowing us an insight into the wealth, tastes and social standing of successful artists in late Victorian London. The houses that can be viewed from this window are as follows: The house immediately to the left: Prinsep and Leighton built their houses at virtually the same time and remained firm friends until Leighton’s death. -

G F and Mary Watts

G F AND MARY WATTS A WEEK IN ENGLAND EXPLORING THEIR LIFE, WORK AND FRIENDSHIPS Saturday 12 - Saturday 19 September 2020 Arts & Crafts Tours Arts & Crafts Tours G F and Mary Watts Introduction A Week in England Exploring Their This will be a very special private tour of Lives Works and Friendships England in the company of expert Elaine Hirschl Ellis who will offer wonderful insights into Arts & Crafts Tours is offering an extraordinary week of discovering the life, work and friendships of G F and Mary private collections, behind-the-scenes tours, hidden gems and private Watts. You will enjoy private visits to some of dinners for US Patrons of Watts Gallery Trust. You are invited to join the UK’s finest museums and private collections this tour to see major works of the great British artist George Frederic including Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village, Watts OM RA (1817-1904) and the designer Mary Watts (1849-1938). Eastnor Castle and the Palaces of Westminster. Image: Andy Newbold Photography Image: Andy Newbold George Frederic Watts OM RA Arts & Crafts Tours G F Watts was widely considered to be one of With over 25 years of experience, Arts & Crafts the world’s greatest artists. He was not only an Tours is known for small group tours utilizing outstanding painter, but also a talented sculptor their amazing network of contacts which and draughtsman, and trail-blazing muralist. Watts allow for special entrance to places generally became a cultural icon who championed a new unavailable to the public, all accompanied by role for art as a means of symbolically expressing expert guides. -

The Gentleman's Library Sale

Montpelier Street, London I 30 January 2019 Montpelier Street, The Gentleman’s Library Sale Library The Gentleman’s The Gentleman’s Library Sale I Montpelier Street, London I 30 January 2019 25163 The Gentleman’s Library Sale Montpelier Street, London | Wednesday 30 January 2019 Part I: 10am Silver Pictures Collectors Part II: 2pm Tribal Arts Furniture, Works of Art, Clocks and Carpets BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PRESS ENQUIRIES IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street Senior Sale Coordinator [email protected] In February 2014 the United Knightsbridge Laurel Kemp States Government announced London SW7 1HH +44 (0) 20 7393 3855 CUSTOMER SERVICES the intention to ban the import www.bonhams.com [email protected] Monday to Friday of any ivory into the USA. Lots 8.30am – 6pm containing ivory are indicated by VIEWING Carpets +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 the symbol Ф printed beside the Sunday 27 January Helena Gumley-Mason Lot number in this catalogue. 11am to 3pm +44 (0) 20 8963 2845 SALE NUMBER REGISTRATION Monday 28 January [email protected] 25163 9am to 4.30pm IMPORTANT NOTICE Tuesday 29 January Furniture Please note that all customers, CATALOGUE 9am to 4.30pm Thomas Moore irrespective of any previous activity £15 +44 (0) 20 8963 2816 with Bonhams, are required to BIDS [email protected] complete the Bidder Registration Please see page 2 for bidder Form in advance of the sale. The +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 information including after-sale European Sculpture & Works form can be found at the back of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax collection and shipment To bid via the internet please visit of Art every catalogue and on our www.bonhams.com Michael Lake website at www.bonhams.com Please see back of catalogue and should be returned by email or +44 (0) 20 8963 2813 for important notice to bidders Please note that bids should [email protected] post to the specialist department be submitted no later than 24 or to the bids department at ILLUSTRATIONS hours before the sale.