AFTERWORD the Adventure of the French Deception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhodes Memorial the Immense and Brooding Spirit Still Shall Quicken and Control

FREE Please support our advertisers who make this free guide possible PLEASE TIP Cape Town EMPOWERMENT VENDORS GATEWAYGUIDES Rhodes Memorial The immense and brooding spirit still shall quicken and control. Living he was the land, and dead, his soul shall be her soul! Muizenberg Rhodes Memorial Rudyard Kipling 1 False Bay To advertise here contact Hayley Burger: 021 487 1200 • [email protected] Earl Grey, the Colonial Secretary, Rhodes did not ‘miss the bus’ as Neville Chamberlain said; he started 100 YEAR proposed a massive statue of a company, ‘The Gold Fields of South Africa Ltd’. His next move was to Cape Point ANNIVERSARY a human figure on the summit turn over all properties and interests to shareholders to run the business, 2012 of Signal Hill, overlooking Cape and in return, Rhodes and his partner, Charles Rudd, would receive Town, that would rival the statue a ‘founders share’ which was two-fifteenths of the profits. This of Christ in Rio de Janeiro and the worked out to up to 400,000 pounds a year. The shareholders, Statue of Liberty in New York. The after a number of years, resented this arrangement - as a idea was met with horror and was result, Rhodes became a ordinary shareholder with a total squashed immediately. The figure of 1,300,000 pounds worth of shares. He also invested in was to be of Cecil John Rhodes, other profitable mining companies on the Rand. In 1890, a man of no royalty, neither hero the first disaster hit the gold industry. As the mines 2 nor saviour; so, who was this became deeper, they hit a layer of rock containing To advertise here contact Hayley Burger: man and what did he do that a pyrites which retarded the then recovery process. -

Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Honors Theses Undergraduate Research 2014 Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model Kirk Maynard Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Maynard, Kirk, "Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model" (2014). Honors Theses. 92. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors/92 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. 2014 Kirk Maynard HONS 497 [TEACHING STRATEGIES: HOW TO EXPLAIN THE HISTORY AND THEMES OF ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM TO HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS USING THE INTEGRATIVE MODEL] Abstract: The purpose of my thesis is to create a guideline for teachers to explain art history to students in an efficient way without many blueprints and precedence to guide them. I have chosen to focus my topic on Abstract Expressionism and the model that I will be using to present the concept of Abstract Expressionism will be the integrated model instructional strategy. -

Obama and the Black Political Establishment

“YOU MAY NOT GET THERE WITH ME …” 1 OBAMA & THE BLACK POLITICAL ESTABLISHMENT KAREEM U. CRAYTON Page | 1 One of the earliest controversies involving the now historic presidential campaign of Barack Obama was largely an unavoidable one. The issue beyond his control, to paraphrase his later comment on the subject, was largely woven into his DNA.2 Amidst the excitement about electing an African-American candidate to the presidency, columnist Debra Dickerson argued that this fervor might be somewhat misplaced. Despite his many appealing qualities, Dickerson asserted, Obama was not “black” in the conventional sense that many of his supporters understood him to be. While Obama frequently “invokes slavery and Jim Crow, he does so as one who stands outside, one who emotes but still merely informs.”3 Controversial as it was, Dickerson’s observation was not without at least some factual basis. Biologically speaking, for example, Obama was not part of an African- American family – at least in the traditional sense. The central theme of his speech at the 2004 Democratic convention was that only a place like America would have allowed his Kenyan father to meet and marry his white American mother during the 1960s.4 While 1 Special thanks to Vincent Brown, who very aptly suggested the title for this article in the midst of a discussion about the role of race and politics in this election. Also I am grateful to Meta Jones for her helpful comments and suggestions. 2 See Senator Barack Obama, Remarks in Response to Recent Statements b y Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr. -

Chesterton & Sons

t.h. Chesterton & sons Chartered Surveyors ' Auctioneers & Valuers ESTATE AGENTS -: .:: , .i :a¡ ' þ. iì 116 Kensington High Street ;l London Wg 7RW Tel.01-937 1234 rå-l 2 Cale Street Chelsea Green ¡', London SW3 3OU ;1 Tel.01-589 5211 þ ,i I 40 Connaught Street Hyde Park London WZ 2AB YOTJN(i S'I'RDtìT, LOOt(INC; NOR'I'H, JUNIi 189() Tel. O1 -262 7202 26 Clifton Road Maida Vale London W9 1SX Tel. 01 -289 1001 ..:i--. Hornton House Drayson Mews London WB 4LY Tel.01-937 8020 Building Surveying Division 9 Wood Street Cheapside London EC2V 7AR Tel.01-606 3055 Commercial and lndustrial Departments THE KENSINGTON SOCIETY Annual R.port 197 0-7 L The Kensington Society t'.-\'11ìo\ II.R.II. PIìI\CIìSS AI,IC.]D, COLI\TIìSS OI. A:IIII,ONIì I'RIlSli)tlN',l' 'l'IIlì lìI(;II't' I lO\. I,ORD IIURCOll13, t;.c.tr., r<.n.n. VI('Ii-I'IìLSIDEN'TS 'I'IIìi I)O\\I..\(II.]Iì fI.\IìCIIION].]SS OF CIIOLN'IONDIìLEY ,I'IIIi R]" RIì\¡, 'fIIIì I,OIìD BISIIOP OF IitìNSING'ION 't'lIIr) l,AI)Y Sl'OCKS T. COI )NCII, F. r'.r'.s.,r. Nfiss Jean '\lex¡ntler \Ir. \\¡illi¿m Glimes, Jlr'. I lrrr.lr' ,\rrtics Sir John Pope-Ht'nness)', c.B.E., F.Iì..4,., tr.S.r\, 'l'he Ifun. \lr. .Justice lJ¡rrv Tl-rc IIon. NIr. Justice liarminski \lr. \\/. \\:. ììclle¡", F.Iì.III51.s., I-.It.I.tl.¡. trIr. Oliver \'Iessel, c.l.n. Sil Ilugh C'asson, R.I).I., Ir.tr.I.tt.r\, L:rcl¡' Norn"ran, ¡.e. -

Sherlock's Relationships in the Twenty-First Century

1 Sherlock's Relationships in the Twenty-First Century BA Thesis Stijn Koster 3653099 Gageldijk 84b 3566 MG Utrecht English Language and Culture dr. Roselinde Supheert 29 June 2014 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Adaptations 4 Chapter 2: Who is Sherlock? 6 Chapter 3: The Relationship Between Holmes and Watson 10 Chapter 4: Sherlock and the Others 15 4.1 Mycroft Holmes 16 4.2 Jim Moriarty 18 4.3 Gregory Lestrade / Scotland Yard 20 4.4 Mary Morstan 21 4.5 Irene Adler 23 4.6 Molly Hooper 23 4.7 A Conclusion to the Characters 25 Conclusion 26 Bibliography 27 3 Introduction There are very few people who have never heard of Sherlock Holmes. That is not because everyone has read Arthur Conan Doyle's stories about this famous character. Ever since the stories were first published in 1887 they have been adapted into screen films and television series. During these 100 years the character has also transformed. Newer adaptations have also been inspired by previous adaptations, which changes the Holmes that was first created by Conan Doyle into a character that the everyone who adapts him contributes to. Film adaptations are a filmmaker's interpretations of stories and characters. In recent years several Sherlock Holmes adaptations have been created. Many alterations regarding the original stories by Doyle have been made to please the contemporary audience. Due to limited time and space, this thesis shall focus mainly on the BBC series Sherlock created by Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, which first aired in 2010. Gatiss and Moffat have analysed the characters and stories thoroughly; they have then deconstructed them en reassembled them in twenty-first century England. -

Tri-Borough Executive Decision Report

A4 Executive Decision Report Decision maker and Leadership Team 15 July 2020 date of Leadership Forward Plan reference: 05672/20/K/A Team meeting or (in the case of individual Lead Portfolio: Cllr Mary Weale, Lead Member Member decisions) the for Finance and Customer Delivery earliest date the decision will be taken Report title 2019/20 Financial Outturn Reporting officer Mike Curtis – Executive Director Resources Key decision Yes Access to information Public classification 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY General Fund Revenue Position 1.1. The overall position on services is a small overspend of £143,000 (including Grenfell). In addition, there is an underspend of £10.4m on corporate items, of which £3.8m is due to the full implementation of the Treasury Management Strategy and increased investment income which has been reported for most of the year. This is a one-off underspend and budgets have been adjusted for 2020/21. The remainder relates to the corporate contingency and the provision set aside for the pension fund liability which has not been required during the year. Further details are set out in paragraph 5.2. 1.2. After the proposed transfer of the £11.3m to earmarked reserves, the Council will maintain its General Fund working balance at £10m. This £10m is in line with what is agreed in the Council’s Medium-Term Financial Strategy and reserves policy. General Fund Capital Programme 1.3. The total original General Fund Capital Programme budget in 2019/20, including budget carried forward from the 2018/19 was £163.066m. During the first three quarters of the year, there was a total variance of £91.249m giving a current budget of £71.817m. -

The Gothic Revival Character of Ecclesiastical Stained Glass in Britain

Folia Historiae Artium Seria Nowa, t. 17: 2019 / PL ISSN 0071-6723 MARTIN CRAMPIN University of Wales THE GOTHIC REVIVAL CHARACTER OF ECCLESIASTICAL STAINED GLASS IN BRITAIN At the outset of the nineteenth century, commissions for (1637), which has caused some confusion over the subject new pictorial windows for cathedrals, churches and sec- of the window [Fig. 1].3 ular settings in Britain were few and were usually char- The scene at Shrewsbury is painted on rectangular acterised by the practice of painting on glass in enamels. sheets of glass, although the large window is arched and Skilful use of the technique made it possible to achieve an its framework is subdivided into lancets. The shape of the effect that was similar to oil painting, and had dispensed window demonstrates the influence of the Gothic Revival with the need for leading coloured glass together in the for the design of the new Church of St Alkmund, which medieval manner. In the eighteenth century, exponents was a Georgian building of 1793–1795 built to replace the of the technique included William Price, William Peckitt, medieval church that had been pulled down. The Gothic Thomas Jervais and Francis Eginton, and although the ex- Revival was well underway in Britain by the second half quisite painterly qualities of the best of their windows are of the eighteenth century, particularly among aristocratic sometimes exceptional, their reputation was tarnished for patrons who built and re-fashioned their country homes many years following the rejection of the style in Britain with Gothic features, complete with furniture and stained during the mid-nineteenth century.1 glass inspired by the Middle Ages. -

Earl's Court and West Kensington Opportunity Area

Earl’s Court and West Kensington Opportunity Area - Ecological Aspirations September 2010 www.rbkc.gov.uk www.lbhf.gov.uk Contents Site Description..................................................................................................................... 1 Holland Park (M131).......................................................................................................... 1 West London and District Line (BI 2) ................................................................................. 4 Brompton Cemetery (BI 3)................................................................................................. 4 Kings College (L8)............................................................................................................. 5 The River Thames and tidal tributaries (M031) .................................................................. 5 St Paul's Open Space (H&FL08) ....................................................................................... 5 Hammersmith Cemetery (H&FL09) ................................................................................... 6 Normand Park (H&FL11)................................................................................................... 6 Eel Brook Common (H&FL13) ........................................................................................... 7 British Gas Pond (H&FBI05).............................................................................................. 7 District line north of Fulham Broadway (H&FBI07G)......................................................... -

Cardiff 19Th Century Gameboard Instructions

Cardiff 19th Century Timeline Game education resource This resource aims to: • engage pupils in local history • stimulate class discussion • focus an investigation into changes to people’s daily lives in Cardiff and south east Wales during the nineteenth century. Introduction Playing the Cardiff C19th timeline game will raise pupil awareness of historical figures, buildings, transport and events in the locality. After playing the game, pupils can discuss which of the ‘facts’ they found interesting, and which they would like to explore and research further. This resource contains a series of factsheets with further information to accompany each game board ‘fact’, which also provide information about sources of more detailed information related to the topic. For every ‘fact’ in the game, pupils could explore: People – Historic figures and ordinary population Buildings – Public and private buildings in the Cardiff locality Transport – Roads, canals, railways, docks Links to Castell Coch – every piece of information in the game is linked to Castell Coch in some way – pupils could investigate those links and what they tell us about changes to people’s daily lives in the nineteenth century. Curriculum Links KS2 Literacy Framework – oracy across the curriculum – developing and presenting information and ideas – collaboration and discussion KS2 History – skills – chronological awareness – Pupils should be given opportunities to use timelines to sequence events. KS2 History – skills – historical knowledge and understanding – Pupils should be given -

Y\5$ in History

THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A5 In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for The Degree Mi ST Master of Arts . Y\5$ In History by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California May, 2016 Copyright by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Gargoyles of San Francisco: Medievalist Architecture in Northern California 1900-1940 by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr., and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History at San Francisco State University. <2 . d. rbel Rodriguez, lessor of History Philip Dreyfus Professor of History THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California 2016 After the fire and earthquake of 1906, the reconstruction of San Francisco initiated a profusion of neo-Gothic churches, public buildings and residential architecture. This thesis examines the development from the novel perspective of medievalism—the study of the Middle Ages as an imaginative construct in western society after their actual demise. It offers a selection of the best known neo-Gothic artifacts in the city, describes the technological innovations which distinguish them from the medievalist architecture of the nineteenth century, and shows the motivation for their creation. The significance of the California Arts and Crafts movement is explained, and profiles are offered of the two leading medievalist architects of the period, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan. -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Italian Renaissance: Envisioning Aesthetic Beauty and the Past Through Images of Women

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN Carolyn Porter Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Carolyn Elizabeth Porter 2010 All Rights Reserved “DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN” A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CAROLYN ELIZABETH PORTER Master of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Furman University, 2004 Director: ERIC GARBERSON ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe a huge debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions that have helped this project along for many years. Without their generous support in the form of financial assistance, sound professional advice, and unyielding personal encouragement, completing my research would not have been possible. I have been fortunate to receive funding to undertake the years of work necessary for this project. Much of my assistance has come from Virginia Commonwealth University. I am thankful for several assistantships and travel funding from the Department of Art History, a travel grant from the School of the Arts, a Doctoral Assistantship from the School of Graduate Studies, and a Dissertation Writing Assistantship from the university. -

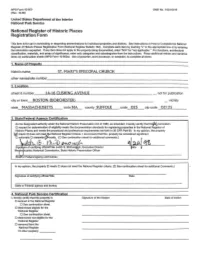

Applicable." for Functions, Architectural Classification, Materials, and Areas of Significance, Enter Only Categories and Subcategories from the Instructions

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form Is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name._---'-___--=s'-'-T~ • .:....M::...A=R~Y_"S~EP=_=I=SC=O=_'_'PA:....:..=.L~C:.:..H~U=R=C=H..!.._ ______________ other names/site number___________________________________ _ 2. Location city or town_-=.B=O-=.ST..:...O=..:...,:N:.....J(..::;D-=O:...,:.R.=C=.H.:.=E=ST..:...E=R.=) ________________ _ vicinity state MASSACHUSETTS code MA county SUFFOLK code 025 zip code 02125 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that thi~ nomination o request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60.