Indigenous Water Rights & Global Warming in Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Reassessment of the Reverend John Mcdougall

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2017-02 Finding Directions West: Readings that Locate and Dislocate Western Canada's Past Colpitts, George; Devine, Heather University of Calgary Press http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51827 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Attribution 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca FINDING DIRECTIONS WEST: READINGS THAT LOCATE AND DISLOCATE WESTERN CANADA’S PAST Edited by George Colpitts and Heather Devine ISBN 978-1-55238-881-5 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Municipal Guide

Municipal Guide Planning for a Healthy and Sustainable North Saskatchewan River Watershed Cover photos: Billie Hilholland From top to bottom: Abraham Lake An agricultural field alongside Highway 598 North Saskatchewan River flowing through the City of Edmonton Book design and layout by Gwen Edge Municipal Guide: Planning for a Healthy and Sustainable North Saskatchewan River Watershed prepared for the North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance by Giselle Beaudry Acknowledgements The North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance would like to thank the following for their generous contributions to this Municipal Guide through grants and inkind support. ii Municipal Guide: Planning for a Healthy and Sustainable North Saskatchewan Watershed Acknowledgements The North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance would like to thank the following individuals who dedicated many hours to the Municipal Guide project. Their voluntary contributions in the development of this guide are greatly appreciated. Municipal Guide Steering Committee Andrew Schoepf, Alberta Environment Bill Symonds, Alberta Municipal Affairs David Curran, Alberta Environment Delaney Anderson, St. Paul & Smoky Lake Counties Doug Thrussell, Alberta Environment Gabrielle Kosmider, Fisheries and Oceans Canada George Turk, Councillor, Lac Ste. Anne County Graham Beck, Leduc County and City of Edmonton Irvin Frank, Councillor, Camrose County Jolee Gillies,Town of Devon Kim Nielsen, Clearwater County Lorraine Sawdon, Fisheries and Oceans Canada Lyndsay Waddingham, Alberta Municipal Affairs Murray Klutz, Ducks -

Brazeau River Gas Plant

BRAZEAU RIVER GAS PLANT Headquartered in Calgary with operations focused in Western Canada, KEYERA operates an integrated Canadian-based midstream business with extensive interconnected assets and depth of expertise in delivering midstream energy solutions. Image input specifications Our business consists of natural gas gathering and processing, Width 900 pixels natural gas liquids (NGLs) fractionation, transportation, storage and marketing, iso-octane production and sales and diluent Height 850 pixels logistic services for oil sands producers. 300dpi We are committed to conducting our business in a way that 100% JPG quality balances diverse stakeholder expectations and emphasizes the health and safety of our employees and the communities where we operate. Brazeau River Gas Plant The Brazeau River gas plant, located approximately 170 kilometres southwest of the city of Edmonton, has the capability PROJECT HISTORY and flexibility to process a wide range of sweet and sour gas streams with varying levels of NGL content. Its process includes 1968 Built after discovery of Brazeau Gas inlet compression, sour gas sweetening, dehydration, NGL Unit #1 recovery and acid gas injection. 2002 Commissioned acid gas injection system Brazeau River gas plant is located in the West Pembina area of 2004 Commissioned Brazeau northeast Alberta. gas gathering system (BNEGGS) 2007 Acquired 38 kilometre sales gas pipeline for low pressure sweet gas Purchased Spectra Energy’s interest in Plant and gathering system 2015 Connected to Twin Rivers Pipeline 2018 Connected to Keylink Pipeline PRODUCT DELIVERIES Sales gas TransCanada Pipeline System NGLs Keylink Pipeline Condensate Pembina Pipeline Main: 780-894-3601 24-hour emergency: 780-894-3601 www.keyera.com FACILITY SPECIFICATIONS Licensed Capacity 218 Mmcf/d OWNERSHIP INTEREST Keyera 93.5% Hamel Energy Inc. -

Information Package Watercourse

Information Package Watercourse Crossing Management Directive June 2019 Disclaimer The information contained in this information package is provided for general information only and is in no way legal advice. It is not a substitute for knowing the AER requirements contained in the applicable legislation, including directives and manuals and how they apply in your particular situation. You should consider obtaining independent legal and other professional advice to properly understand your options and obligations. Despite the care taken in preparing this information package, the AER makes no warranty, expressed or implied, and does not assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. For the most up-to-date versions of the documents contained in the appendices, use the links provided throughout this document. Printed versions are uncontrolled. Revision History Name Date Changes Made Jody Foster enter a date. Finalized document. enter a date. enter a date. enter a date. enter a date. Alberta Energy Regulator | Information Package 1 Alberta Energy Regulator Content Watercourse Crossing Remediation Directive ......................................................................................... 4 Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 4 How the Program Works ....................................................................................................................... -

Upper North Saskatchewan River and Abraham Lake Bull Trout Study, 2002 - 2003

Upper North Saskatchewan River and Abraham Lake Bull Trout Study, 2002 - 2003 CONSERVATION REPORT SERIES The Alberta Conservation Association is a Delegated Administrative Organization under Alberta’s Wildlife Act. CCONSERVATIONONSERVATION RREPORTEPORT SSERIESERIES 25% Post Consumer Fibre When separated, both the binding and paper in this document are recyclable Upper North Saskatchewan River and Abraham Lake Bull Trout Study, 2002 – 2003 Marco Fontana1, Kevin Gardiner2 and Mike Rodtka2 1 Alberta Conservation Association 113 ‐ 1 Street Cochrane, Alberta, Canada T4C 1B4 2 Alberta Conservation Association 4919 – 51 Street Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, Canada T4T 1B3 Report Series Editor PETER AKU KELLEY J. KISSNER Alberta Conservation Association 59 Hidden Green NW #101, 9 Chippewa Rd Calgary, AB T3A 5K6 Sherwood Park, AB T8A 6J7 Conservation Report Series Type Data, Technical ISBN printed: 978‐0‐7785‐6573‐4 ISBN online: 978‐0‐7785‐6574‐1 Publication No.: T/165 Disclaimer: This document is an independent report prepared by the Alberta Conservation Association. The authors are solely responsible for the interpretations of data and statements made within this report. Reproduction and Availability: This report and its contents may be reproduced in whole, or in part, provided that this title page is included with such reproduction and/or appropriate acknowledgements are provided to the authors and sponsors of this project. Suggested Citation: Fontana, M., K. Gardiner, and M. Rodtka. 2006. Upper North Saskatchewan River and Abraham Lake Bull -

Working Together: Our Stories Best Practices and Lessons Learned in Aboriginal Engagement Table of Contents

Working Together: Our Stories Best Practices and Lessons Learned in Aboriginal Engagement Table of Contents Parks Canada wishes to First photo: Message from Alan Latourelle, Métis Interpreter Bev Weber explaining traditional Métis art to Chief Executive Officer, Parks Canada ..........2 Jaylyn Anderson (4 yrs old). Rocky Mountain House National acknowledge and thank the Historic Site of Canada (© Parks Canada) Message from Elder Stewart King, many Aboriginal partners Second photo: Wasauksing First Nation and member Qapik Attagutsiak being interviewed by her daughter, Parks of Parks Canada’s Aboriginal Canada staff Kataisee Attagutsiak. Workshop on Places of and communities that it is Ecological and Cultural Significance for Sirmilik National Park Consultative Committee ................................4 of Canada, Borden Peninsula, Nunavut. (© Parks Canada / fortunate to work with for Micheline Manseau) Introduction ....................................................6 Third photo: their generous contribution Chapter 1 Craig Benoit of Miawpukek First Nation explains the defining features of Boreal Felt Lichen to Terra Nova National Park of Connecting With Aboriginal Partners ...........10 and collaboration. Canada staff Janet Feltham and Prince Edward Island National Park of Canada staff Kirby Tulk. (© Parks Canada / Robin Tulk) Chapter 2 Working Together to Protect Our Heritage .....20 Compiled by: Aboriginal Affairs Secretariat Chapter 3 Parks Canada Agency Gatineau, Quebec Presenting Our Special Place Together .......34 CAT. NO R62-419/2011 Conclusion ..................................................48 ISBN 978-1-100-53286-8 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Chief Executive Officer of Parks Canada Agency, 2011 always evolving, we can still celebrate our many and the vision we have as an Agency. Our staff is accomplishments. I would like to take this oppor- committed to include and work with Aboriginal tunity to tell you why I’m grateful and give thanks communities. -

Brazeau Subwatershed

5.2 BRAZEAU SUBWATERSHED The Brazeau Subwatershed encompasses a biologically diverse area within parts of the Rocky Mountain and Foothills natural regions. The Subwatershed covers 689,198 hectares of land and includes 18,460 hectares of lakes, rivers, reservoirs and icefields. The Brazeau is in the municipal boundaries of Clearwater, Yellowhead and Brazeau Counties. The 5,000 hectare Brazeau Canyon Wildland Provincial Park, along with the 1,030 hectare Marshybank Ecological reserve, established in 1987, lie in the Brazeau Subwatershed. About 16.4% of the Brazeau Subwatershed lies within Banff and Jasper National Parks. The Subwatershed is sparsely populated, but includes the First Nation O’Chiese 203 and Sunchild 202 reserves. Recreation activities include trail riding, hiking, camping, hunting, fishing, and canoeing/kayaking. Many of the indicators described below are referenced from the “Brazeau Hydrological Overview” map locat- ed in the adjacent map pocket, or as a separate Adobe Acrobat file on the CD-ROM. 5.2.1 Land Use Changes in land use patterns reflect major trends in development. Land use changes and subsequent changes in land use practices may impact both the quantity and quality of water in the Subwatershed and in the North Saskatchewan Watershed. Five metrics are used to indicate changes in land use and land use practices: riparian health, linear development, land use, livestock density, and wetland inventory. 5.2.1.1 Riparian Health 55 The health of the riparian area around water bodies and along rivers and streams is an indicator of the overall health of a watershed and can reflect changes in land use and management practices. -

Bighorn Backcountry Public Land Use Zones 2019

Edson 16 EDMONTON Hinton 47 22 Jasper 39 734 Bighorn Backcountry PLUZs 2 22 National Bighorn The Bighorn Backcountry is managed to ensure the Backcountry Park protection of the environment, while allowing responsible 11 and sustainable recreational use. The area includes more than Rocky 11 5,000 square kilometres (1.2 million acres) of public lands east Mountain House 54 of Banff and Jasper National Parks. 734 27 The Bighorn Backcountry hosts a large variety of recreational Banff National 22 activities including camping, OHV and snow vehicle use, hiking, shing, Park hunting and cycling. CALGARY 1 It is your responsibility to become familiar with the rules and activities allowed in this area before you visit and to be informed of any trail closures. Please refer to the map and chart in this pamphlet for further details. Visitors who do not follow the rules could be ned or charged under provincial legislation. If you have any concerns about the condition of the trails and campsites or their appropriate use, please call Alberta Environment and Parks at the Rocky Mountain House Ofce, 403-845-8250. (Dial 310-0000 for toll-free service.) For current trail conditions and information kiosk locations, please visit the Bighorn Backcountry website at www.alberta.ca Definitions for the Bighorn Backcountry Motorized User ✑ recreational user of both off-highway vehicles and snow vehicles. Equestrian User or ✑ recreational user of both horses and/or mules, used for trail riding, pack Equine horse, buggy/cart, covered wagon or horse-drawn sleigh. Non-Motorized User ✑ recreational user which is non-motorized except equestrian user or equine where specified or restricted. -

This Work Is Licensed Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. THE TIGER BEETLES OF ALBERTA (COLEOPTERA: CARABIDAE, CICINDELINI)' Gerald J. Hilchie Department of Entomology University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E3. Quaestiones Entomologicae 21:319-347 1985 ABSTRACT In Alberta there are 19 species of tiger beetles {Cicindela). These are found in a wide variety of habitats from sand dunes and riverbanks to construction sites. Each species has a unique distribution resulting from complex interactions of adult site selection, life history, competition, predation and historical factors. Post-pleistocene dispersal of tiger beetles into Alberta came predominantly from the south with a few species entering Alberta from the north and west. INTRODUCTION Wallis (1961) recognized 26 species of Cicindela in Canada, of which 19 occur in Alberta. Most species of tiger beetle in North America are polytypic but, in Alberta most are represented by a single subspecies. Two species are represented each by two subspecies and two others hybridize and might better be described as a single species with distinct subspecies. When a single subspecies is present in the province morphs normally attributed to other subspecies may also be present, in which case the most common morph (over 80% of a population) is used for subspecies designation. Tiger beetles have always been popular with collectors. Bright colours and quick flight make these beetles a sporting and delightful challenge to collect. -

HDP 2006 05 Report 1

Report #1 1998 CWS Air Surveys In response to a general lack of knowledge on the abundance and distribution of the Harlequin Duck within Alberta, the Canadian Wildlife Service in cooperation with Alberta Environment undertook helicopter surveys of the eastern slopes of Alberta in 1998 and 1999. In 1998 the survey area encompassed streams along the eastern slopes of Alberta between the communities of Grande Cache and Nordegg. Ground truthing was provided by foot surveys on the McLeod River conducted by Bighorn Wildlife Technologies Ltd. Local area biologists helped with selection of blocks of streams to be surveyed where harlequins were most likely to occur and assisted in the helicopter surveys. Helicopter survey methods are detailed in Gregoire et al. (1999). Global Positioning Coordinates (GPS) were recorded for all sightings as well as survey start and end points. The Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) coordinate system was used for recording sightings of Harlequin Duck and other wildlife. Survey start and end points were recorded in Latitude and Longitude. Five digit numbers hand written in the field survey reports represent the BSOD (now WHIMIS) ID number for that observation. What this document contains. - A summary of the 1998 surveys (Gregoire et al. 1999. Canadian Wildlife Service Technical Report Series No. 329), - The field results for the helicopter survey conducted between the Brazeau and North Saskatchewan Rivers - The results of a foot survey on the Blackstone River. , · Harlequin L?.uck ·surveys in the Centr~I - .Eastern Slopes o.f Albert9: . ·Spring 1998. T - • ~ Paul Gr~goire, Jeff Kneteman and Jim Allen . .-"• r, ~ ~-. Prairie and Northern Region 1999 .1;._-, - 1 ,~ .Canadian Wildlife Service '' ,· ~: ,. -

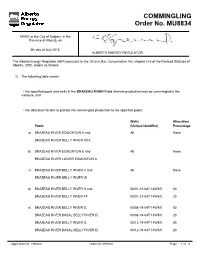

BRAZEAU RIVER Field Wherein Production May Be Commingled in the Wellbore, And

COMMINGLING Order No. MU8834 MADE at the City of Calgary, in the Province of Alberta, on 5th day of July 2018. ALBERTA ENERGY REGULATOR The Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) pursuant to the Oil and Gas Conservation Act, chapter O-6 of the Revised Statutes of Alberta, 2000, orders as follows: 1) The following table shows • the specified pools and wells in the BRAZEAU RIVER Field wherein production may be commingled in the wellbore, and • the allocation factors to prorate the commingled production to the specified pools: Wells Allocation Pools (Unique Identifier) Percentage a) BRAZEAU RIVER EDMONTON A and All None BRAZEAU RIVER BELLY RIVER XXX b) BRAZEAU RIVER EDMONTON E and All None BRAZEAU RIVER LOWER EDMONTON A c) BRAZEAU RIVER BELLY RIVER V and All None BRAZEAU RIVER BELLY RIVER W d) BRAZEAU RIVER BELLY RIVER X and 00/01-21-047-14W5/0 80 BRAZEAU RIVER BELLY RIVER FF 00/01-21-047-14W5/0 20 e) BRAZEAU RIVER BELLY RIVER X, 00/08-19-047-14W5/0 80 BRAZEAU RIVER BASAL BELLY RIVER D, 00/08-19-047-14W5/0 20 BRAZEAU RIVER BELLY RIVER X, 00/12-19-047-14W5/0 80 BRAZEAU RIVER BASAL BELLY RIVER D, 00/12-19-047-14W5/0 20 Application No. 1909250 Order No. MU8834 Page 1 of 8 BRAZEAU RIVER BELLY RIVER X, and 00/01-24-047-15W5/0 80 BRAZEAU RIVER BASAL BELLY RIVER D 00/01-24-047-15W5/0 20 f) BRAZEAU RIVER BELLY RIVER X, 00/15-20-047-14W5/0 45 BRAZEAU RIVER BASAL BELLY RIVER D, and 00/15-20-047-14W5/0 45 BRAZEAU RIVER BASAL BELLY RIVER Y 00/15-20-047-14W5/0 10 g) BRAZEAU RIVER BELLY RIVER X, 00/07-27-047-14W5/0 50 BRAZEAU RIVER BASAL BELLY RIVER M, 00/07-27-047-14W5/0 -

The Rocky Mountain Region

Chapter 02 5/5/06 3:40 PM Page 18 Chapter 2 The Rocky Mountain Region What makes the Rocky Mountain region a unique part of Alberta? My Dad works for the Canadian National Railway, and our family moved to Jasper because of his work. I think living in the Rocky Mountain region is like living in the middle of a silvery crown. In the Rocky Mountains, you can see snow on the mountain tops, even during the summer. My new friends at school pointed out a mountain called Roche Bonhomme (rosh boh num), a French phrase that means “good fellow rock.” It is also called Old Man Mountain. If you stand in Jasper and look up at the mountains in the northeast, you will see what looks like a sleeping man. Whenever I leave my house, I always look up at him and silently send him my greetings. On my birthday, I was given my own camera. I took the picture you see here and many others. This is a beautiful area in all four seasons. My photos tell part of Alberta’s story. I think you can really see the side view of the sleeping man’s face in this photo of Roche Bonhomme. 18 NEL Chapter 02 5/5/06 3:40 PM Page 19 What I Want to Know… …About the Rocky Mountain Region The Rocky Mountain region begins at the southwestern border of Alberta. It is part of the Rocky Mountain chain. The mountains run northwest and southeast along the western side of North America.