Rotuma, a Changing Mobility, 1978-1983

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotuman Educational Resource

Fäeag Rotuam Rotuman Language Educational Resource THE LORD'S PRAYER Ro’ạit Ne ‘Os Gagaja, Jisu Karisto ‘Otomis Ö’fāat täe ‘e lạgi, ‘Ou asa la ȧf‘ȧk la ma’ma’, ‘Ou Pure'aga la leum, ‘Ou rere la sok, fak ma ‘e lạgi, la tape’ ma ‘e rȧn te’. ‘Äe la nāam se ‘ạmisa, ‘e terạnit 'e ‘i, ta ‘etemis tē la ‘ā la tạu mar ma ‘Äe la fạu‘ạkia te’ ne ‘otomis sara, la fak ma ne ‘ạmis tape’ ma rē vạhia se iris ne sar ‘e ‘ạmisag. ma ‘Äe se hoa’ ‘ạmis se faksara; ‘Äe la sại‘ạkia ‘ạmis ‘e raksa’a, ko pure'aga, ma ne’ne’i, ma kolori, mou ma ke se ‘äeag, se av se ‘es gata’ag ne tore ‘Emen Rotuman Language 2 Educational Resource TABLE OF CONTENTS ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY 4 ROGROG NE ROTUMA 'E 'ON TẠŪSA – Our history 4 'ON FUẠG NE AS TA ROTUMA – Meaning behind Rotuma 5 HẠITOHIẠG NE FUẠG FAK PUER NE HANUA – Chiefly system 6 HATAG NE FĀMORI – Population 7 ROTU – Religion 8 AGA MA GARUE'E ROTUMA – Lifestyle on the island 8 MAK A’PUMUẠ’ẠKI(T) – A treasured song 9 FŪ’ÅK NE HANUA GEOGRAPHY 10 ROTUMA 'E JAJ(A) NE FITI – Rotuma on the map of Fiji 10 JAJ(A) NE ITU ’ HIFU – Map of the seven districts 11 FÄEAG ROTUẠM TA LANGUAGE 12 'OU ‘EA’EA NE FÄEGA – Pronunciation Guide 12-13 'ON JĪPEAR NE FÄEGA – Notes on Spelling 14 MAF NE PUKU – The Rotuman Alphabet 14 MAF NE FIKA – Numbers 15 FÄEAG ‘ES’ AO - Useful words 16-18 'OU FÄEAG’ÅK NE 'ÄE – Introductions 19 UT NE FAMORI A'MOU LA' SIN – Commonly Frequented Places 20 HUẠL NE FḀU TA – Months of the year 21 AG FAK ROTUMA CULTURE 22 KATO’ AGA - Traditional ceremonies 22-23 MAMASA - Welcome Visitors and returnees 24 GARUE NE SI'U - Artefacts 25 TĒFUI – Traditional garland 26-28 MAKA - Dance 29 TĒLA'Ā - Food 30 HANUJU - Storytelling 31-32 3 ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY Legend has it that Rotuma’s first inhabitants Consequently, the two religious groups originated from Samoa led by Raho, a chief, competed against each other in the efforts to followed by the arrival of Tongan settlers. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Cited in the text Anderson, A., S. Bedford, G. Clark, I. Lilley, C. Sand, G. Summerhayes and R. Torrence 2001 ‘A List of Lapita Sites Containing Dentate-stamped Pottery’ in G.R Clark, A.J. Anderson and T. Vunidilo (eds) The Archaeology of Lapita Dispersal in Oceania, pp. 1–13, Terra Australis 17, Pandanus Press, Canberra. Best, S. 1984 Lakeba: A Prehistory of a Fijian island, Unpublished PhD thesis. Department of Anthropology, University of Auckland. Blust, R. 1987 ‘Lexical Reconstruction and Semantic Reconstruction: The Case of Austronesian “House” Words’, Diachronica 4(1/2):79–106. Brewster, A.B. 1922 The Hill Tribes of Fiji, J.B. Lippincott, Philadelphia. Burns, A. 1960 A Report of the Commission of Enquiry into the Natural Resources and Population Trends of the Colony of Fiji, 1959. Report No. 1, Government of Fiji, Suva. Capell, A. 1941 A New Fijian Dictionary, Australasian Medical Publishing Co., Sydney. Capell, A. and R.H. Lester 1941 ‘Local Divisions and Movements in Fiji (part 1)’, Oceania 11:313–341. Capell, A. and R.H. Lester 1941 ‘Local Divisions and Movements in Fiji (part 2)’, Oceania 12:21–48. Carnarvon. 1875 Despatch from Earl Carnarvon to Sir A.H. Gordon, dated 4 March 1875, ‘On the policy to be planned in future Government of Fiji’. Section V, ‘Title of Land’. Churchward, C. M. 1940 Rotuman Grammar and Dictionary, Australasian Medical Publishing Co., Sydney. Clark, G. 2000 Post-Lapita Fiji: Cultural Transformation in the Mid-Sequence. Unpublished PhD thesis, The Australian National University, Canberra. Clark, G. and A. Anderson 2001 ‘The Pattern of Lapita Settlement in Fiji’, Archaeology in Oceania 36(3):77–88. -

Survival Guide on the Road

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd PAGE ON THE YOUR COMPLETE DESTINATION GUIDE 42 In-depth reviews, detailed listings ROAD and insider tips Vanua Levu & Taveuni p150 The Mamanuca & Yasawa Groups p112 Ovalau & the Lomaiviti Group Nadi, Suva & Viti Levu p137 p44 Kadavu, Lau & Moala Groups p181 PAGE SURVIVAL VITAL PRACTICAL INFORMATION TO 223 GUIDE HELP YOU HAVE A SMOOTH TRIP Directory A–Z .................. 224 Transport ......................... 232 Directory Language ......................... 240 student-travel agencies A–Z discounts on internatio airfares to full-time stu who have an Internatio Post offices 8am to 4pm Student Identity Card ( Accommodation Monday to Friday and 8am Application forms are a Index ................................ 256 to 11.30am Saturday Five-star hotels, B&Bs, able at these travel age Restaurants lunch 11am to hostels, motels, resorts, tree- Student discounts are 2pm, dinner 6pm to 9pm houses, bungalows on the sionally given for entr or 10pm beach, campgrounds and vil- restaurants and acco lage homestays – there’s no Shops 9am to 5pm Monday dation in Fiji. You ca Map Legend ..................... 263 to Friday and 9am to 1pm the student health shortage of accommodation ptions in Fiji. See the ‘Which Saturday the University of nd?’ chapter, p 25 , for PaciÀ c (USP) in ng tips and a run-down hese options. Customs Regulations E l e c t r Visitors can leave Fiji without THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Dean Starnes, Celeste Brash, Virginia Jealous “All you’ve got to do is decide to go and the hardest part is over. So go!” TONY WHEELER, COFOUNDER – LONELY PLANET Get the right guides for your trip PAGE PLAN YOUR PLANNING TOOL KIT 2 Photos, itineraries, lists and suggestions YOUR TRIP to help you put together your perfect trip Welcome to Fiji ............... -

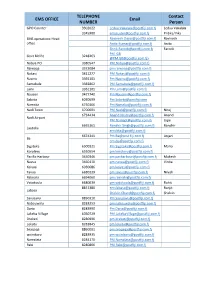

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Tikina Nailaga Sustainable Development Plan 2018 - 2038 1

TIKINA NAILAGA SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2018 - 2038 1 NACULA SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PLAN Presented by Tikina Nailaga Development Committee Contributors Apolosa Robaigau, Rusila Savou-Wara, Kesaia Tabunakawai, Alfred Ralifo, Metui Tokece (WWF-Pacific), Tikina Nailaga Community Representatives Layout & Design: Kitione Roko & Kalo Williams Edited by: Vilisite Tamani & Amelia Makutu Finalised: July 2018 Funded by: Supported by: CONTENTS Acknowledgement 010104 Foreword 05 Summary 06 Vision/Mission/Objective 07 List of Thematic Areas 08 Background 09 Socio-Economic Background 10 The Process of Developing the Sustainable District Development Plan 11 Alignment to Fiji’s National Frameworks 12 Governance and Implementation Structure 13 Summary Costs for Thematic Areas 14 Thematic Areas and Activities 15 Annexes 30 Acknowledgement The Nailaga Sustainable Development Plan is the result of an extensive 5-year (2013-2017) consultation and collaboration process with invaluable input from the following donors, partner organisations, government ministries and individuals. The people of the United States of America through USAID and PACAM Programme and the people of Australia through Australian Aid Programme for funding the completion of this Tikina Nailaga District Sustainable Development Plan. The Government of Fiji, through the relevant ministries that contributed to the development of the plan i.e. The Commissioner Western’s Office, District Office Ba, Department of Land Use and Planning, Ba Provincial Office, Ministry of Education. the plan. World Wide Fund for nature Pacific Office, for leading the facilitation process during the development of Mr Jo Vale and Jeremai Tuwai , the two former Mata ni Tikina (District representatives) who played an important role during the community consultation process . The people of Nailaga District for their participation and contribution towards the development of the plan. -

Fara Way Rotuma

from Stories of the Southern Sea, by Lawrence Winkler Published as a Kindle book on December 26, 2013 Fara Way Rotuma “Their bodies were curiously marked with the figures of men, dogs, fishes and birds upon every part of them; so that every man was a moving landscape.” George Hamilton, Pandora’s surgeon, 1791 The whole scene was a moving landscape, directly under us, just over two hundred years after Captain Edwards had arrived on the HMS Pandora. He had been looking for the Bounty. We would find another. The pilot of our Britten-Norman banked off the huge cloud he had found over six hundred kilometers north of the rest of Fiji, and sliced down into it sideways, like he was cutting a grey soufflé. Nothing could have prepared us for the magnificence that opened up below, with the dispersal of the last gasping mists. A fringing reef, barely holding back the eternal explosions of rabid frothing foam and every blue in the reflected cosmos, encircled every green in nature. On the edge of both creations were the most spectacular beaches in the Southern Sea. Captain Edwards had called it Grenville Island. Two hundred years earlier, it was named Tuamoco by de Quiros, before he went on to establish his doomed New Jerusalem in Vanuatu. But that was less important for the moment. We had reestablished level flight, and were lining up on the dumbbell- shaped island’s only rectangular open space, a long undulating patch of grass, between the mountains and the ocean. Hardly more than a lawn bowling pitch anywhere else, here it was the airstrip, beside which a tiny remote paradise was waving all its arms. -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ -

Tropical Cyclone Winston UNOSAT Damage Assessment Activities In

Tropical Cyclone Winston UNOSAT Damage Assessment Activities in Viti Levu Island, Fiji 09 March 2016 - Report 9 March 2016 Geneva, Switzerland UNOSAT Contact: Postal Address: Email: [email protected] UNITAR – UNOSAT, IEH T: +41 22 767 4020 (UNOSAT Operations) Chemin des Anémones 11, 24/7 hotline: +41 75 411 4998 CH-1219, Genève, Suisse 1 UNITAR - UNOSAT | UNOSAT Damage Assessment Activities in Viti Levu Island - FIJI | 9 March 2016 Tropical Cyclone Winston in Fiji (19 February 2016 – 9 March 2016) Overview A powerful tropical cyclone named “Winston” struck the Southern Pacific and was heading towards the coasts of Fiji. UNITAR - UNOSAT on behalf of UN OCHA activated the International Space Charter on 19 February 2016. On the 20th of February 2016, the cyclone made landfall at 06:30 UTC (18:30 local time) over the north-eastern coast of Viti Levu (Fiji), the main island of the archipelago. The cyclone tracked west across the country, causing damage in four divisions (Western, Central, Eastern and Northern) with more concerns on the Western and Central divisions. According to FIJI Flash Appeal Tropical Cyclone Winston published by UNOCHA on 4 March 2016, 350,000 people living in the cyclone’s path could have been affected (170.000 female and 180,000 male) - equivalent to 40 per cent of Fiji’s population. This includes 120,000 children under the age of 18 (58,000 female and 62,000 male) and more than 3,100 people with disabilities. UNOSAT Damage Assessment UNOSAT triggered the space charter on behalf of UNOCHA the 19th of February 2016 and requested satellite imagery over the areas defined by UNOCHA based on the proximity to the cyclone track, wind speed values and related potential population exposure. -

Poverty Maps) in Republic of Fiji (2003-2009)

Report No.: 63842-FJ Republic of Fiji Public Disclosure Authorized Poverty Trends, Profiles and Small Area Estimation (Poverty Maps) in Republic of Fiji (2003-2009) September 15, 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective June 7, 2011) Currency Unit = Fijian Dollar USD 1.00 = FJ$ 1.76991 FJ$ 1 = USD 0.565000 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADePT Software Platform for Automated Economic Analysis AusAID Australian Agency for International Development DSW Department of Social Welfare GIC Growth Incidence Curve FAO Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations FAP Family Assistance Program FIBOS Fiji Island Bureau of Statistics HIES Household Income and Expenditure Surveys pAE Per Adult Expenditure Regional Vice President: James W. Adams Country Director: Ferid Belhaj Sector Director: Emmanuel Jimenez Sector Manager: Xiaoqing Yu Task Team Leader: Oleksiy Ivaschenko Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... v Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... vii 1 Background ........................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Poverty methodology........................................................................................................................... -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

Issues of Concern to Rotumans Abroad

ISSUES OF CONCERN TO ROTUMANS ARROAD: A VIEW FROM THE ROTUMA WEBSITE Alan Howard Jan Rensel University of Hawaii at Manoa THE ISLAND OF ROTUMA is relatively remote, located 465 kilometers north of the northernmost island in the Fiji group, and only slightly closer to Futuna, its nearest neighbor. Rotuma has been politically affiliated with Fiji for more than a century, first as a British colony following cession in 1881 and since 1970 as part of the independent nation. Rotuma's people are, however, culturally and linguistically distinct, having strong historic relationships with Polynesian islands to the east, especially Tonga, Samoa, and Futuna. Today, approximately 85 percent of those who identify them selves as Rotuman or part-Rotuman live overseas, mostly on the island of Viti Levu in Fiji, but with substantial numbers in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, and England. Although this article is based primarily on postings from the Rotuma Website, which was created by Alan Howard in 1996, it is informed by research begun by Alan in 1959 over a two-year period on the island of Rotuma and among Rotumans in Fiji. Jan's first visit was in 1987, and we have returned ten times since then for periods ranging from a week to six months. For the past two decades, we have also made multiple visits to all the major overseas Rotuman communities in addition to keeping in touch with Rotuman friends from around the globe via home visits, telephone, e-mail, and, most recently, Facebook. Over the years, we have published a number of articles concerning the Rotuman diaspora and Rotuman communities abroad (Howard 1961; Howard and Howard 1977; Howard Pacific Studies, Vol.