5. Engaging with Missionaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Law and Indigenous Resistance at Moreton Bay 1842-1855

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Southern Queensland ePrints [2005] ANZLH E-Journal Traditional law and Indigenous Resistance at Moreton Bay 1842-1855 LIBBY CONNORS* On the morning of 5 January 1855 when the British settlers of Moreton Bay publicly executed the Dalla-Djindubari man, Dundalli, they made sure that every member of the Brisbane town police was on duty alongside a detachment of native police under their British officer, Lieutenant Irving. Dundalli had been kept in chains and in solitary for the seven months of his confinement in Brisbane Gaol. Clearly the British, including the judge who condemned him, Sir Roger Therry, were in awe of him. The authorities insisted that these precautions were necessary because they feared escape or rescue by his people, a large number of whom had gathered in the scrub opposite the gaol to witness the hanging. Of the ten public executions in Brisbane between 1839 and 1859, including six of Indigenous men, none had excited this much interest from both the European and Indigenous communities.1 British satisfaction over Dundalli’s death is all the more puzzling when the evidence concerning his involvement in the murders for which he was condemned is examined. Dundalli was accused of the murders of Mary Shannon and her employer the pastoralist Andrew Gregor in October 1846, the sawyer William Waller in September 1847 and wounding with intent the lay missionary John Hausmann in 1845. In the first two cases the only witnesses were Mary Shannon’s five year old daughter and a “half- caste” boy living with Gregor whose age was uncertain but described as about ten or eleven years old. -

13 Relationship and Communality: an Indigenous

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship 13 RELATIONSHIP AND COMMUNALITY: AN INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE ON KNOWLEDGE AND EXPRESSION Maroochy Barambah1 PROFESSOR ANNE FITZGERALD We’re going to talk about indigenous peoples and law, and this session is going to be chaired by Dr Terry Cutler. I don’t think Terry needs any further introduction to you, and I’m sure this is going to be a fascinating session. Maroochy Barambah and Ade Kukoyi have been known to me and Brian for many years. In fact I actually first met Maroochy in New York when she was studying opera singing there. The film in which she starred, Black River, had actually just won the Paris Opera Film of the Year Award. The commentator for this session will be Professor Susy Frankel from New Zealand, who’s been very much involved with indigenous IP issues in New Zealand. Terry, over to you. DR TERRY CUTLER Thank you Anne. It gives me huge pleasure to chair this session. At the beginning of our conference we had a very moving welcome to country. Then we tend to proceed to marginalise, or make very unwelcome, any discussion that isn’t within an Anglo-Saxon, or a Commonwealth Club framework. I think one of the great gaps in public policy discussion in Australia is our neglect of this whole area of traditional knowledge and the role of indigenous people in intellectual property discussions. This is even worse I 1 Maroochy Barambah is an Australian Aboriginal mezzo-soprano singer and songwoman and law-woman of the Turrbal-Dippil people from the Brisbane region. -

Kerwin 2006 01Thesis.Pdf (8.983Mb)

Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author Kerwin, Dale Wayne Published 2006 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts, Media and Culture DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1614 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366276 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author: Dale Kerwin Dip.Ed. P.G.App.Sci/Mus. M.Phil.FMC Supervised by: Dr. Regina Ganter Dr. Fiona Paisley This dissertation was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts at Griffith University. Date submitted: January 2006 The work in this study has never previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any University and to the best of my knowledge and belief, this study contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the study itself. Signed Dated i Acknowledgements I dedicate this work to the memory of my Grandfather Charlie Leon, 20/06/1900– 1972 who took a group of Aboriginal dancers around the state of New South Wales in 1928 and donated half their gate takings to hospitals at each town they performed. Without the encouragement of the following people this thesis would not be possible. To Rosy Crisp, who fought her own battle with cancer and lost; she was my line manager while I was employed at (DATSIP) and was an inspiration to me. -

Tom Petrie's Reminiscences

I TOM PETRIE'S REMINISCENCES OF EARLY QUEENSLAND (Dating from 1837.) RECORDED BY HIS DAUGHTER. BRISBANE: WATSON , FERGUSON & CO.. 1904. [COPYRIGHT.] This is a blank page To MY FATHER, TOM PETRIE, WHOSE FAITHFUL MEMORY HAS SUPPLIED THE MATERIAL FOR THIS BOOK. PRINTED BY WATSON, FERGUSON &' CO. QUEEN ST., BRISBANE. This is a blank page This is a blank page NOTE. THE greater portion of the contents of this book first ap- peard in the " Queenslander " in the form of articles, and when those referring to the aborigines were pubished, Dr. Roth, author of " Ethnological Studies," etc., wrote the following letter to that paper :- TOM PETRIE' S REMINISCENCES (By C.C.P.) TO THE EDITOR. SIR,-lt is with extreme interest that I have perused the remarkable series of articles appearing in the Queenslander under the above heading, and sincerely trust that they will he subsequently reprinted. The aborigines of Australia are fast dying out, and with them one of the most interesting phases in the history and development of man. Articles such as these, referring to the old Brisbane blacks, of whom I believe but one old warrior still remains, are well worth permanently recording in convenient book form-they are, all of them, clear, straight-forward statements of facts- many of which by analogy, and from early records, I have been able to confirm and verify-they show an intimate and profound knowledge of the aboriginals with whom they deal, and if only to show with what diligence they have been written, the native names are correctly, i.e., rationally spelt. -

Zach's Ceremony Film Premier Awareness & Fundraiser 19 MARCH 2017 Elder and Country Acknowledgement Introduction Waddamull

Zach’s Ceremony Film Premier Awareness & Fundraiser 19 MARCH 2017 Elder and Country Acknowledgement Introduction Waddamulli, Good Evening. I have it on very good authority that in order to engage with you all as an audience, and hopefully share ideas, observations and experiences, I must first offer you all something of myself. This sharing of myself, has not always been a comfortable reality for me. Life sometimes provides hard and damaging lessons about trust. My former reluctance has been borne of circumstances which elicit a response: Fool me once - shame on you, Fool me twice – shame on me. I have no doubts that I do not stand alone in this context. Tonight, I offer a story, some knowledge and something of myself. I am Linda, I am an Aboriginal Woman, I am a Birrigubba Mother, I am a learner, and I am a contributor. My recent family heritage is evidenced in the official colonial documentation dating back to 1845. Our family presence was first “officially” recorded in Kamilaroi Country (NSW), and further built upon by six (6) generations of family and cultural connection to the Whitsunday Coast North Queensland – Birragubba Country. My people, have of course, enjoyed an undocumented existence for many thousands of years prior to being “accounted for” in the Colonial/Eurocentric record books. Acknowledgement It is appropriate that I now take a formal moment in acknowledgment of the cultural authorities that provide for our safe gathering here this evening. That cultural authority rests, completely, with the traditional peoples of (that which is now) the greater Brisbane area: The Turrbal Peoples north of the Brisbane River, The Jaggera & Ugarapul Peoples south of the Brisbane River, The Manangahalli, to the south east, The Minjerriba of Stradbroke Island, The Ngugi of Moreton Island, and West across the mountains to the Undanbi. -

Two Representative Tribes of Queensland with an Inquiry Concerning the Origin of the Australian Race

f«G :REBREilSlllliE otIEKSeW'I•-:::••:•:;•••• .•• ••....:..,;.•.;.•;.;:•;.::;• %„^ ja.M:N:--M^rM:iW i9 .'^^^ THE LIBRARY , OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES E hart te fau— E toro te jaaro— E nau te taata." [/'H:x-UsJ-c^ to TWO REPRESENTATIVE TRIBES OF QUEENSLAND [A// Rights Reserved^ TWO REPRESENTATIVE TRIBES OF QUEENSLAND WITH AN IN^n{r CONCE%NING THE ORIGIN OF THE AUSTRALIAN %ACE BY JOHN MATHEW, M.A., B.D. AUTHOR OF "EAGLEHAWK AND CROW," "AUSTRALIAN ECHOES," ETC. WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY Prof. A. H. KEANE, LL.D., F.R.A.I., F.R.G.S. LATE VICE-PRESIDENT R. ANTHROP. INSTITUTE AUTHOR OF "ethnology," " MAN PAST AND PRESENT," "THE WORLD'S PEOPLES," ETC. AND A MAP AND UX ILLUSTRATIONS T. FISHER UNWIN LONDON • LEIPSIC Adelphi Terrace Inselstrasse 20 1910 DEDICATED TO J. H. MACFARLAND, Esq., M.A., LL.D., MASTER OF ORMOND COLLEGE, VICE-CHANCELLOR OF MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY, AND A MEMBER OF THE BOARD FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE ABORIGINES IN THE STATE OF VICTORIA, AS A MARK OF ESTEEM AND A TOKEN OF APPRECIATION OF HIS SERVICES TO THE CAUSE OF LEARNING. CONTENTS PACE CHAP. - Introduction - - - xi - Preface . - - xxi I. Inquiry concerning the Origin of the Australian Race 25 II. The Country of the Kabi and Wakka Tribes - - - - - <i) III. Physical and Mental Characters 72 — — —Clothing - IV. Daily Life Shelter Food ^ V. Man-Making and Other Ceremonies VI. Disease and Treatment—Death—Burial and Mourning 1 10 VII. Art — Implements — Utensils —Weapons —Corroborees VIII. Social Organisation IX. The Family—Kinship and Marriage X. Religion and Magic XI. -

Evolve Therapeutic Services Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Evolve Therapeutic Services (Queensland Health) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Wellbeing Cards Guide Evolve Therapeutic Services (Queensland Health) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Wellbeing Cards Guide Published by the State of Queensland (Queensland Health), November 2020 © State of Queensland (Queensland Health) 2020 All rights reserved. Reproduction and or distribution of some or all of the work, without written authorisation. Copyright of the original photographs remain unchanged and is retained by the original copyright holder. For more information contact: Evolve Therapeutic Services, Child and Youth Mental Health Services, Children’s Health Queensland Health and Hospital Services, Queensland Health, GPO Box 48, Brisbane QLD 4001, email: [email protected] Disclaimer: The content presented in this publication is distributed by the Queensland Government as an information source only. The State of Queensland makes no statements, representations or warranties about the accuracy, completeness or reliability of any information contained in this publication. The State of Queensland disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation for liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages and costs you might incur as a result of the information being inaccurate or incomplete in any way, and for any reason reliance was placed on such information. Page 2 of 32 Please note: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this publication and the associated cards may contain images of people who may have passed away. Page 3 of 32 Acknowledgement We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable work of Graham Gee, Pat Dudgeon, Clinton Schultz, Amanda Hart, and Kerrie Kelly (2013) for their creation of a detailed, yet elegant and practical framework to describe Social and Emotional Wellbeing from the perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. -

12. Cultural Heritage

12. Cultural Heritage Northern Link Phase 2 – Detailed Feasibility Study CHAPTER 12 CULTURAL HERITAGE September 2008 Contents 12. Cultural Heritage 12-1 12.1 Description of the Existing Environment 12-1 12.1.1 Cultural Heritage Significance 12-1 12.1.2 Commonwealth Legislation 12-2 12.1.3 State Legislation 12-2 12.1.4 Local Legislation 12-2 12.1.5 Approach 12-3 12.1.6 Aboriginal Heritage 12-3 12.1.7 Non Indigenous Heritage 12-8 12.2 Impact Assessment 12-17 12.2.1 Western Freeway Connection 12-18 12.2.2 Toowong Connection 12-18 12.2.3 Driven Tunnels 12-19 12.2.4 Kelvin Grove Connection 12-25 12.2.5 Inner City Bypass Connection 12-27 12.2.6 Proposed Ventilation Outlet Sites 12-27 PAGE i 12. Cultural Heritage This chapter addresses Part B, Section 5.8, of the Terms of Reference (ToR), which require the EIS to describe existing values for indigenous and non-indigenous cultural heritage areas and objects that may be affected by Northern Link activities. The ToR also require that the EIS prepare cultural heritage surveys as relevant, to determine the significance of any cultural heritage areas or items and assist with the preparation of Cultural Heritage Management Plans to protect any areas or items of significance. The ToR also require that the EIS provide a description of any likely impacts on cultural heritage values, and to recommend means of mitigating any negative impacts. 12.1 Description of the Existing Environment Cultural heritage focuses on aspects of the past which people value and which are important in identifying who we are. -

Turrbal People

THE TURRBAL RESPONSE TO THE QLD GOVT CONSULTATION PAPER ON THE REVIEW OF THE CULTURAL HERITAGE ACTS Prepared by Ade Kukoyi For & on behalf of the Turrbal Assoc & the Turrbal people. August 2019. 1 1.0 WHO’S WHO IN THE ZOO - THE TURRBAL PEOPLE & THEIR COUNTRY - BRISBANE The detailed accounts and in some cases, scanty records of the earliest ticket-of-leave convicts ( Pamphlet, Parsons and Finnegan), and explorers Oxley, Cunningham and others such as Fyans, Ridley who made the contact with the original inhabitants of the Brisbane area have been corroborated largely by the accounts of Thomas Petrie. 1.1 Tom Petrie's Reminiscences of Early Queensland by Constance Campbell Petrie (1904), is undoubtedly one of the most detailed account of early European contacts with Aborigines in South East Queensland, particularly Brisbane. Tom Petrie was born in Scotland in 1831 and arrived in Brisbane in 1837 with his father Andrew, as a young six- year old boy. His life-long experience of living with the Brisbane Aborigines, written by his daughter Constance, represents an invaluable work of social history which vividly describes life in the Moreton Bay penal settlement from the 1830s. He lived and grew up with the original inhabitants of the Brisbane area, which he knew as the Turrbal. As a member of one of Brisbane’s founding families, Tom Petrie grew up on the colonial frontier. He is arguably the on e of th e primary sources available about the culture, customs and beliefs of the original inhabitants of the Brisbane area. The reason for this is straight forward - whilst the other writers were mostly ‘observers’ or ‘passing through’, Tom Petrie lived and grew up with the Aborigines, and spoke the Turrbal language fluently. -

Richard Carroll Thesis

Re-presenting the Past: Authenticity and the Historical Novel A novel and exegesis by Richard Carroll BA (UQ), Honours First Class (QUT) Creative Writing and Literary Studies Discipline Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology Submitted as a requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ii Keywords Aboriginal people, appropriation, authenticity, Brisbane, creative writing process, culture studies, fact/fiction dichotomy, genre studies, historical novel, historiography, literary studies, practice-led research, protocols for non- Indigenous authors, Queensland history, representation, research and aesthetics in fiction, Tom Petrie, whiteness, white writing black. iii Abstract The practice-led project consists of a 51,000 word historical novel and a 39,000 word exegesis that explores the defining elements of historical fiction and the role it plays in portraying the past. The creative work Turrwan (great man), tells the story of Tom Petrie, an early Queensland settler who arrived at the Moreton Bay Penal Colony in 1837 at the age of six. Tom was unusual in that he learnt the language of the local Turrbal people and was accepted as one of their own. The novel explores relationships between the Aboriginal people and settlers with the aim of heightening historical awareness and understanding of this divisive era in Queensland’s history. I believe that literature has neglected the fictionalising of the early history of Brisbane and that my novel could fill this gap. The project is a combination of qualitative and practice-led research: qualitative through the exegesis which consists of mainly discursive data, and practice-led through the creative work. In response to questions raised in the process of writing the story, the investigation explores the historical novel in an attempt to better understand the nature of the genre and how this knowledge could inform the creative work. -

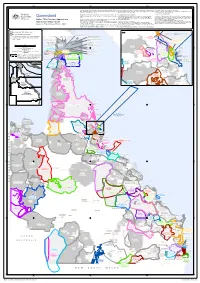

Queensland for That Map Shows This Boundary Rather Than the Boundary As Per the Register of Native Title Databases Is Required

140°0'E 145°0'E 150°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for that map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at portion where their data has been used. Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Maritime boundaries data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents and Queensland 2006. - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give no - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for registration), undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - compensation applications. fitness for purpose of the information provided. Native Title Claimant Applications applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. In return for you receiving this information you agree to release and Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen through Determinations shown on the map include: indemnify the Commonwealth and third party data suppliers in respect of all claims, and Determination Areas the Federal Court. -

16629 Dixon Et Al 2006 Back

Index This is an index of some of the more important terms from Chapter 6,of the names of Australian Aboriginal languages (or dialects), and of loan words from Australian languages (including some words of uncertain origin and some, like picaninny, wrongly thought of as Aboriginal in origin). Variant spellings are indexed either in their alphabetical place or in parentheses after the most usual spelling. References given in bold rype are to the main discussion of a loan word or language. Aboriginal art, 239-40 Baagandji, xiii, 27-8,58,100, 148, Aboriginal Embassy,244 192,195 Aboriginal Flag,244 baal (bael,bail), 22, 205-6,213, 218 Aboriginal time,236 Bajala,43 Aboriginal way,244 balanda,222 Aboriginaliry,244 bale,see baal acrylic art,240 balga,125 adjigo (adjiko), 33, 118,214 ball art,108 Adnyamathanha, xiii, 14,39-40,56, bama,162,163,214 103,174 bandicoot, 50-1 alcheringa (alchuringa),47, 149 Bandjalang, xiii, 20,25-6, 103,119, alunqua,107,212-13 127, 129,132, 137 Alyawarra,46-7 bandy-bandy, 99 amar,see gnamma hole bangala�27,107, 126,213 amulla,107 bangalow,27,121,213 anangu,162, 163 banji, 164 ancestral beings (and spirits),241 Bardi,xiii, 151,195 Anmatjirra, 46 bardi (grub) (barde, bardee,bardie), apology,246 16,30,101-2 Arabana,xiii, 41,187 bardy,see bardi Aranda,xiii, 46-7, 107, 117, 120, bark canoe,239 149-50,155,169,172-3 bark hut,239 ardo,see nardoo bark painting,240 Arrernte,see Aranda barramundi (barra, barramunda), 90, art,239-40 215 Arunta,see Aranda beal,see belah assimilation,243 bel,see baal Awabakal, xiii, 20, 161, 163, 167,196 belah (belar),126, 132,213 .,.