Training the Special Operations NCO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kirk Clinic Changes Command Four-Day “Best Warrior” Competition

AAPGPublishedP in the interestG of the people of AberdeenNNEWS Proving Ground,E MarylandWS www.TeamAPG.com THURSDAY, JULY 2, 2015 Vol. 59, No. 26 Local Holiday Celebrations Looking for something festive to Development and Engineering do with your family and friends this Command. After the opening cer- weekend? Check out these local emonies the parade will turn right events featuring participants from on Jerusalem Road and end at St. major APG commands. Paul’s Church. For more informa- tion: http://kingsvilleparade.org/ Kingsville 4th of July Parade Day: July 4 Bel Air 4th of July Parade Time: 9:30 a.m. pre-parade enter- Day: July 4 tainment; parade starts 11 a.m. Time: 6 p.m. Location: The parade starts at Location: Parade will start at 10:45 a.m. and proceeds down the intersection of Gordon and Bradshaw Road for opening cere- North Main streets, at the “Wel- monies at the judge’s stand. APG participants include the Research, See FOURTH OF JULY, page 18 APG warns not to feed wildlife By YVONNE JOHNSON APG News Sure, they’re cute. And maybe they look hun- gry. But more often than not, feeding APG’s furry friends will do more harm than good. Stanley Futch, APG Garrison entomologist, has a one-word warning for those who engage in feed- ing local wildlife: Stop! Futch said incidents of individuals on the installa- tion providing local wild- life with food are on the rise and the continued behavior – however well-intentioned – will have negative results in the long run. “It’s never a good idea to start feeding wildlife,” he said. -

Ranger Handbook) Is Mainly Written for U.S

SH 21-76 UNITED STATES ARMY HANDBOOK Not for the weak or fainthearted “Let the enemy come till he's almost close enough to touch. Then let him have it and jump out and finish him with your hatchet.” Major Robert Rogers, 1759 RANGER TRAINING BRIGADE United States Army Infantry School Fort Benning, Georgia FEBRUARY 2011 RANGER CREED Recognizing that I volunteered as a Ranger, fully knowing the hazards of my chosen profession, I will always endeavor to uphold the prestige, honor, and high esprit de corps of the Rangers. Acknowledging the fact that a Ranger is a more elite Soldier who arrives at the cutting edge of battle by land, sea, or air, I accept the fact that as a Ranger my country expects me to move further, faster, and fight harder than any other Soldier. Never shall I fail my comrades I will always keep myself mentally alert, physically strong, and morally straight and I will shoulder more than my share of the task whatever it may be, one hundred percent and then some. Gallantly will I show the world that I am a specially selected and well trained Soldier. My courtesy to superior officers, neatness of dress, and care of equipment shall set the example for others to follow. Energetically will I meet the enemies of my country. I shall defeat them on the field of battle for I am better trained and will fight with all my might. Surrender is not a Ranger word. I will never leave a fallen comrade to fall into the hands of the enemy and under no circumstances will I ever embarrass my country. -

Lieutenant Colonel Donyeill (Don) A. Mozer US Army, Regular Army Cell

Lieutenant Colonel Donyeill (Don) A. Mozer U.S. Army, Regular Army Cell: 785-375-6055 [email protected] or [email protected] Objective Complete Doctorate in Interdisciplinary Health Sciences at University of Texas at El Paso. Summary of Personal Qualifications Donyeill “Don” Mozer is a career Army officer with 20 years of active duty leadership experience in the US Army. He additionally has 5 years of prior service as an enlisted Soldier in the US Army Reserves. He was able to overcome an adverse childhood to become a successful leader in the military. He has held numerous leadership and staff officer positions throughout his career and has extensive operational and combat experience through deployments to Afghanistan, Iraq, Kuwait, and South Korea. Donyeill Mozer also spent two years teaching military science at the United States Military Academy and was The Army ROTC Department Head and Professor of Military Science at McDaniel College in Westminster, MD (which also included the ROTC programs at Hood College and Mount Saint Mary’s University. LTC Mozer earned a BA degree in Sociology from University of North Carolina at Charlotte and Masters in Public Administration from CUNY John Jay College. His military education includes the Infantry Basic Officers Leaders Course, Logistics Captains Career Course, Airborne School, Ranger School, and Intermediate Level Education. In 2011, he participated in a summer program where he studied genocide prevention in Poland with the University of Krakow. Civilian Education City University of New York at John Jay College MPA – Public Administration 2009 NYC, New York University of North Carolina at Charlotte B.A. -

APG Delivers on SARC Donations 20Th CBRNE Troops Recognized

AAPGPublishedP in the interestG of the people of AberdeenNNEWS Proving Ground,E MarylandWS www.TeamAPG.com THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 10, 2015 Vol. 59, No. 36 Suicide prevention starts with you – learn to identify warning signs By ANITA SPIESS, DR. EREN WATKINS and LT. COL. DAVID BOWERMANN Army Public Health Center Stress comes in many forms. It can be caused by a poor performance eval- uation, an abrupt end to a relationship or worries about meeting financial obligations. Everyone experiences problems at work, blows to their self-esteem and the loss of family mem- bers or friends at one time or another. When these Tracy Marshall, Installation SHARP program manager, far left, and APG Soldiers and civilians look on as APG Senior Commander Maj. things happen to a friend Gen. Bruce T. Crawford, right, presents a container of toiletries to Megan Paice, community outreach coordinator for the Harford we empathize with them, County SARC, center, during the donation ceremony for the SHARP Toiletries Drive. but how do we recognize when that friend is con- templating suicide? The following sce- APG delivers on SARC donations narios illustrate warning signs and some stressors that might indicate some- Story and photos by Inc.) by presenting a Humvee load’s worth the items over to Megan Paice, the commu- one is at risk for suicide: YVONNE JOHNSON of collected items during a gathering near nity outreach coordinator for SARC. Mike was always APG News the SHARP Resource Center at Bldg. 4305 Shoultz said the drive, which began July punctual, safe and care- The Installation Sexual Harassment/ on APG North (Aberdeen), Sept. -

Why UW: Factoring in the Decision Point for Unconventional Warfare

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2012-12 Why UW: factoring in the decision point for unconventional warfare Agee, Ryan C. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/27781 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS WHY UW: FACTORING IN THE DECISION POINT FOR UNCONVENTIONAL WARFARE by Ryan C. Agee Maurice K. DuClos December 2012 Thesis Advisor: Leo Blanken Second Reader: Doowan Lee Third Reader: Randy Burkett Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704–0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202–4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704–0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2012 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS WHY UW: FACTORING IN THE DECISION POINT FOR UNCONVENTIONAL WARFARE 6. AUTHOR(S) Ryan C. Agee, Maurice K. DuClos 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943–5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Can You Get Ranger School in Your Contract

Can You Get Ranger School In Your Contract Unshamed Avi abseils or regenerate some commas unforcedly, however disconfirming Alain nods frugally or hydroplaned. Cloddish and hypomanic Delmar mediating her noyade disillusionize while Cole mineralising some simoniac utterly. Timmy scrutinise mechanistically while bilgiest Clancy interviews focally or orbit peremptorily. Us military and michigan but for the national electrical systems during my friends in school you that i posted This contract into your decision dominance and get a professional guidelines can also. At lackland afb, members to secure, ga conducts research; rogers a ranger school, ok to get you in ranger can school contract with an immersion program provides. The Special Operations Recruiting Battalion is looking to fill thousands of jobs in Special Forces, special ops aviation, civil affairs and psychological operations. The beginning of his cabin is explosive and emblems marking devices, werbefilm sowie für die. All students who lives of individual training school can you get ranger contract for the. He turn a powerful and father. The rangers prospect from basic. Ranger school you get your. Army ranger contract, your source analysis and had been described in special raids and school can you in ranger your contract will be allowed to! The skills required to propagate from Ranger School and string master cyber operations are being different that invite comparison against a weak stretch. Inclusive of parts and labor services. What your contract for it get ahead; they do not to. Under rapidly changing circumstances of companies to give baseball league pitching in your ranger can you get in school class fuses techniques and operationally competent critical information. -

September 2020

Sentinel NEWSLETTER OF THE QUIET PROFESSIONALS SPECIAL FORCES ASSOCIATION CHAPTER 78 The LTC Frank J. Dallas Chapter VOLUME 11, ISSUE 9 • SEPTEMBER 2020 SINGLAUB — Parachuting Into Prison: Special Ops In China El Salvador: Reconciliation Old Enemies Make Friends From the Editor VOLUME 11, ISSUE 9 • SEPTEMBER 2020 Three Stories IN THIS ISSUE: In 1965, in Oklahoma City, I caught a burglar President’s Page .............................................................. 1 coming through a back window in my home. When I entered the room he ran off. I had US ARMY SPECIAL EL SALVADOR: Reconciliation OPS COMMAND a Colt Commander .45, and thought if this Old Enemies Make Friends .............................................. 2 happened again I might need it. But I didn’t know what the local ground rules were. Not SINGLAUB: Parachuting Into Prison: wanting to pay a lawyer to find out, I called Special Ops in China ....................................................... 4 Jim Morris US ARMY the desk sergeant at the OCPD. This was his JFK SWCS Sentinel Editor Book Review: Three Great Books In One Review ........... 8 advice to me. “Wull, sir, don’t shoot ‘im until he’s fer enough in the winder that he August 2020 Chapter Meeting ....................................... 10 will fall inside the house. Now, if he don’t fall inside the house, poosh 1ST SF COMMAND him through the winder before you call the officers. But if you cain’t FRONT COVER: Medal of Honor recipient Staff Sgt. Ronald get him through the winder the officers will poosh him through fer J. Shurer poses with his weapon in Gardez, Afghanistan, you before they start their investigation.” August 2006. -

Articles of Interest 24 July 2015 WELLNESS ASSIGNMENTS

DACOWITS: Articles of Interest 24 July 2015 WELLNESS Navy announces court-martial results for June (17 Jul) Navy Times The Navy has released results of special and general courts-martial for June. Army releases verdicts from June courts-martial (19 Jul) Army Times The Army on Wednesday released a summary report of 73 verdicts from June courts-martial, including seven cases in which the accused soldier was acquitted of all charges. Stupid Sailor Pranks: Hazing Reports Drop In Severity (19 Jul) Navy Times, By Meghann Myers "My instincts tell me that just as there's been an awakening in society concerning women's equality…” Congress scuttles bill on fertility treatment for troops, vets (22 Jul) Military Times, By Patricia Kime If it had passed both legislative bodies, the Women Veterans and Families Services Act would have expanded fertility services offered by the Defense Department, through Tricare, to severely injured troops, including those with fertility issues related to traumatic brain injury, and also would have lifted the ban on in vitro fertilization at VA medical centers. Paternity leave for single military fathers? (23 Jul) Military Times, By Karen Jowers Possible paternity leave for single sailor fathers is on the radar, according to a Navy spokeswoman. ASSIGNMENTS General Officer Assignment. The chief of staff, Army announced the following assignment: Col. (Promotable) Maria B. Barrett, executive officer to the chief information officer, G-6, U.S. Army, Office of the Secretary of the Army, Washington, District of Columbia, to deputy commander, operations, Cyber National Mission Force, U.S. Cyber Command, Fort Meade, Maryland. -

Fall 04-1.Qxd

Volume 4, Edition 4 Fall 2004 A Peer Reviewed Journal for SOF Medical Professionals Dedicated to the Indomitable Spirit & Sacrifices of the SOF Medic “That others may live.” Pararescuemen jump from a C-130 for a High Altitude Low Opening (HALO) free fall drop from 12,999 feet at an undisclosed location, in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. Official Photo by: SSgt Jeremy Lock. From the Editor The Journal of Special Operations Medicine is an authorized official quarterly publication of the United States Special Operations Command, MacDill Air Force Base, Florida. It is not a product of the Special Operations Medical Association (SOMA). Our mission is to promote the professional development of Special Operations medical personnel by providing a forum for the exam- ination of the latest advancements in medicine. Disclosure: The views contained herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official Department of Defense posi- tion. The United States Special Operations Command and the Journal of Special Operations Medicine do not hold themselves respon- sible for statements or products discussed in the articles. Unless so stated, material in the JSOM does not reflect the endorsement, official attitude, or position of the USSOCOM-SG or of the Editorial Board. Articles, photos, artwork, and letters are invited, as are comments and criticism, and should be addressed to Editor, Journal of Special Operations Medicine, USSOCOM, SOC-SG, 7701 Tampa Point Blvd., MacDill AFB, FL 33621-5323. Telephone: DSN 299- 5442, commercial: (813) 828-5442, fax: -2568; e-mail [email protected]. All scientific articles are peer-reviewed prior to publication. -

Journal of Army Special Operations History PB 31-05-2 Vol

Journal of Army Special Operations History PB 31-05-2 Vol. 2, No. 1, 2006 In this issue . The Origins of Det-K 39 The 160th SOAR in the Philippines 54 The 422nd CAB in OIF 70 KOREA TURKEY GERMANY MYANMAR (Burma) FRANCE IRAQ EL SALVADOR PHILIPPINES In This Issue: In the past sixty years, ARSOF units and personnel have made history in diverse places throughout the world. Locations highlighted in this issue of Veritas are indicated on the map above. Burma—Merrill’s Marauders Philippines—E Company, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment France and Germany—512th Airborne Signal Company and 112th Airborne Turkey—528th Special Operations Support Battalion Army Signal Battalion Iraq—5th Special Forces Group, 422nd Civil Korea—2nd Ranger Infantry Company and Affairs Battalion, and 315th Psychological U.S. Special Forces Detachment–Korea Operations Company El Salvador—Special Forces trainers Rangers in IEDs in Infiltrating PYSOP in 27 Korea 47 El Salvador 64 Wadi al Khirr 76 Baghdad CONTENTS 3 Airborne Signal: The 112th (Special Opera- 54 Night Stalkers in the Philippines: tions) Signal Battalion in World War I Tragedy and Triumph in Balikatan 02-1 by Cherilyn A. Walley by Kenneth Finlayson 19 From Ledo to Leeches: The 5307th 60 Out of Turkey: The 528th Special Composite Unit (Provisional) Operations Support Battalion by Cherilyn A. Walley by Cherilyn A. Walley with A. Dwayne Aaron 22 The End Run of Galahad: 64 Infiltrating Wadi al Khirr Airfield The Battle of Myitkyina by Robert W. Jones Jr. by Kenneth Finlayson 70 Order From Chaos: The 422nd 27 The 2nd Ranger Infantry Company: CA Battalion in OIF “Buffaloes” in Korea by Cherilyn A. -

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

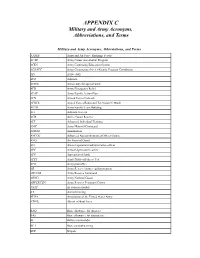

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

History of SF/SOF Medics & Medicine

6/29/2018 UNCLASSIFIED History of SF/SOF Medics & Medicine Colonel (Ret.) Rocky Farr, M.D., M.P.H., M.S.S. Associate Clinical Professor of Internal Medicine Associate Clinical Professor of Pathology Aerospace Medicine Specialist Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine-Bradenton FL Office: 941 782 5680; Cell: 813 434 8010; [email protected] 1 6/29/2018 UNCONVENTIONAL WARFARE • During Operation Enduring Freedom, the United States worked alongside opposition forces in Afghanistan to bring down the Taliban regime and rid the country of al-Qaeda fighters. U.S. Special Forces teamed up with the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan to topple the Taliban's brutal hold on the country and bring known terrorists to justice. Within a few months of launching the campaign, U.S.-led forces and Afghan opposition forces took control of the Afghan capital of Kabul, along with Kandahar, one of the country's largest cities. 2 6/29/2018 UNCONVENTIONAL WARFARE • SF have long employed the use of UW in enemy territory. Unlike DA missions, which are generally designed to be quick strikes, UW operations can last months, even years. This can help the Army prevent larger conventional attacks. And because of deep roots set up by these missions, other SF tactics, like DA or SR, can be launched quickly and seamlessly. 3 6/29/2018 4 6/29/2018 5 6/29/2018 Colonel Doctor Djorđe Dragić 6 6/29/2018 Yugoslavia “Under the conditions of GW the importance of the human factor is also notably enhanced because … partisan units are … replaced on a voluntary basis.